Kristijan Krkač1, Maja Martinović1, Stipe Buzar2

1Department of Marketing, Zagreb School of Economics and Management, Zagreb, 10000, Croatia

2Dubrovnik School of Diplomacy, DIU International University, Dubrovnik, 20000, Croatia

Correspondence to: Stipe Buzar, Dubrovnik School of Diplomacy, DIU International University, Dubrovnik, 20000, Croatia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

In the paper the authors conduct a thought experiment and a conceptual analysis in order to investigate CSR as being done by criminal businesses, and draw some lessons from it in terms of the change in concept of CSR from a value-positive to a value-neutral concept. Also, a revision of the model for solving CSR cases is done by use of the analogy between CSR problem solving and the concept and procedure of “inventing practical things”. The paper identifies CSR as a set of practices, and a possible analogy with “inventing” procedure as a benchmark for identification and solving CSR issues in terms of CSR as an integrative, holistic, and value neutral concept, meaning that CSR ought to be understood as an integral part of any business “being done properly”, and because of that any advertised, deceptive, illusory CSR, or understood as “something additional” to the core business seems to be misguided. The paper tries to show that CSR is value neutral, and in addition that it is an integral, implicit, and at the same time manifested element of a business being done properly.

Keywords:

Corporate Social Irresponsibility, Corporate Social Responsibility, Criminal Businesses, Integral CSR, Inventions, Paradox of CSR Done by Criminal Businesses, Patents of Practical Things, Stakeholders

Cite this paper:

Kristijan Krkač, Maja Martinović, Stipe Buzar, "Fine Young Criminal’s Corporate Social Responsibility:On the Virtues of the Wicked and the Common Good Performed by Egoists", American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 2 No. 5, 2012, pp. 98-106. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20120205.02.

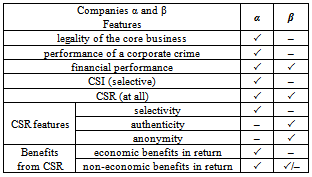

1. Instead of an Introduction: A Strange Case of CSR

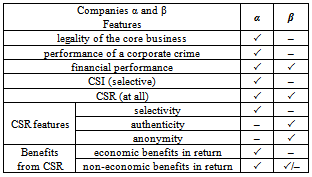

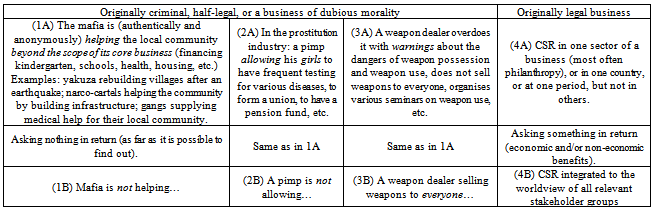

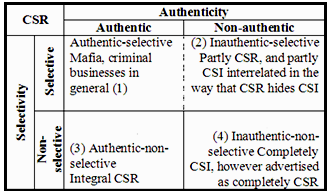

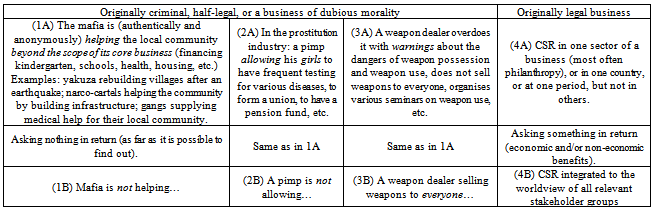

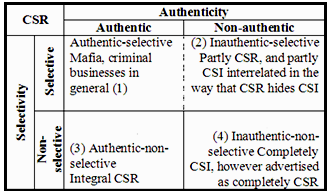

Say that Tom and Jill observe a strange situation in their neighbourhood. After an earthquake a lot of buildings where workers of a local company (Company α as shown in Table 1) live are not safe for living any more. Reparation is badly needed. Unfortunately, the local government simply hasn’t the resources to do anything. The company which initially built these apartments, primarily for their workers, has no intention whatsoever of doing anything about it (in fact, it performed a corporate crime, namely, a kind of conspiracy with a local construction company and some local officials in order to build apartments of quality lower then it is required by various construction standards). What’s more, the company advertises itself as being extremely philanthropic and green. On the other hand, the local mafia (Organisation β as shown in table 1), initially coming from the local community, recognises the need of the local community and by anonymous donation to local construction company repairs all of the buildings (afterwards they find out that the construction company was engaged in a corporate crime so they successfully convince them not to do it anymore). Therefore, one is faced with a simple moral dilemma – how should one compare and decide which of the two actions is less immoral if one action comprises selective CSR (and selective CSI as well) implemented by a legal company, and if another action comprises authentic CSR executed by an essentially criminal organisation? If one has the intuition here, that a legal business is at first sight less morally incorrect in contrast with an illegal one, simply by being legal, then some additional elements should be explicated. The legal company is doing selective CSR and at the same time being completely CSI in some other department of its business. More to that, it uses its CSR in order to conceal it’s CSI, and finally, it makes more money in return from being CSR (say in terms of philanthropy) then it actually spends on it, while the criminal organisation doesn’t do any of this. On the other hand, the legal company is, via this additional element, obviously doing inauthentic CSR, while the criminal organisation is obviously doing authentic CSR, given the fact that it hides it (say that it would be bad for “business” if the public “knew” that they have become soft, so they do it anonymously). An additional point could be that a local legal company performed a corporate crime as described previously (all of these features are shown in Table 1).1Now, one should notice that this dilemma has many varieties all of which are quite important for understanding the basic dilemma, so the whole series of cases should be supplied (some of which are real, others imaginary) as shown in Table 2.2Table 1. A comparison between a legal (α) and an illegal (β) businesses concerning CSR

|

| |

|

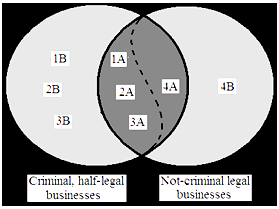

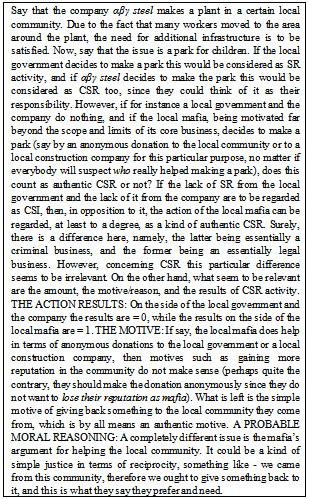

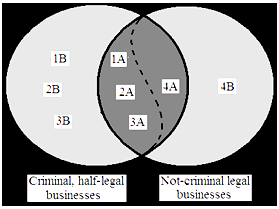

This series of comparisons between these types of cases can reveal various, more or less strange, similarities and dissimilarities among which one is of some importance for the topic of the present paper. ■ If one compares the obviously criminal businesses (1-3B in Table 2) with integral CSR (4B in Table 2), one gets the obvious difference between non-CSR and CSR. However, if comparisons of 1A with 1B, and 2A with 2B, etc. results, as indeed it does, with the observation that legal (or illegal) persons in A’s rather then in B’s manifest some kind of, at least selective and in the same time by all means authentic CSR, then this observation shows something, namely that CSR routines are not necessarily connected or are an exclusive part of originally legal businesses. In another words, they can be a part of all kinds of businesses, criminal, half-legal, and even those of dubious morality. The comparison between 4A and 4B shows the difference between, say, selective CSR (4A) and integral CSR (4B; the problem in 4B is the one of moral justification of transactional change, i.e. changing a mind set or a world-view, or on which grounds such change can be appropriate and morally justified). Furthermore, if one compares the difference between the A’s and the B’s from (1A-B) to (3A-B) with (4A-B), then it seems that the differences are similar, that there is a kind of proportion (as shown in Table 2). These comparisons show something about the CSR phenomenon as well. To be precise, they show that the very phenomenon, or a series of routine practices which one considers as being genuine CSR practices, and in that light as “being good practices,” is in fact value-neutral rather then value-positive. Now, the basic intuition says – why should one consider (compare) criminal business at all? The answer is simple – let’s do it for the sake of argument, namely, in order to investigate the CSR of legal businesses? The results should be, if nothing else, interesting (as shown in Table 3 as a graphical summary of Table 2).  | Figure 1. Types of cases compared in Table 2 presented in terms of Venn’s diagrams (the overlap space creates the mentioned moral dilemma, especially in terms of understanding inauthentic and non-integral CSR) |

Table 2. various cases in criminal, half-legal or businesses of dubious morality compared, especially with legal businesses with selective CSR3

|

| |

|

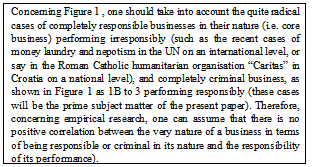

Therefore, at least three issues can be of some interest concerning these comparisons (as shown in Table 2 and in Figure 1 ). Is it possible that authentic CSR appears in essentially criminal, half-legal businesses, and in businesses of dubious morality? Is it possible that the basic, common, and presupposed notion of CSR is in fact value- neutral, since it can appear in legal and essentially extremely responsible core businesses in terms of selective CSR, as well as in illegal (criminal) and essentially extremely irresponsible businesses in terms of authentic CSR? Is it possible and what does it take to practice integral, so to say “invisible” CSR as the natural and essential part of any business whatsoever? These issues will be addressed in the following sections. Namely, the cases show that authentic CSR can appear in essentially illegal and criminal businesses. Furthermore, from the analysis of the particular cases one can clearly see that the basic notion of CSR is in fact value neutral, or that it concerns the “functional good” which manifests all other kinds of “substantial goods” (see Box 1 for radical cases).4Box 1. Radical cases

|

| |

|

Now, the answer to the third question is somewhat more difficult. Namely, in order to answer it one needs to find a practice in which all the needed elements are presented, in order to parallel the notion and the practice-model of CSR which we are looking for. However, arguments for such claims should be the prime subject matter of the investigation. Now, in order to be on the safe side here, the criminal businesses mentioned are not being defended as being, say, not criminal, since indeed they are. However, that these can perform authentic CSR is something that seems to be obvious enough and it will be defended. ■ What’s more, sociologist and criminologist D. Cressey in his important research[2] concluded that corporate criminal behaviour is learned by executives just as street crime is learned by juvenile delinquents. According to the known motto of Robin Hood: “Rob the rich and give to the poor.” ([8]: C-477-8), criminals have a slightly modified version, something like “Rob the rich, and sometimes give to those in need.” Therefore, let us conclude the introduction. While on one hand CSR is widely, on the other CSI is minimally researched, measured, etc. in terms of its detecting its preconditions, causes, motives, and similar, not in terms of particular cases of course. This is partly so because there are some objections to so called “negative approach” to CSR that is to say, from the point of view of CSI. However, if we turn the issue around, and ask – are there organisations which are essentially CSI due to their “core business” yet by all means manifesting and performing complete, authentic, and anonymous CSR (as shown in Table 1) – then the answer should be helpful in order to understand another question, namely – what does it mean to be virtuous and to perform for common good? In addition, if it is possible to answer affirmatively to the first question, then the principal difference between CSR and CSI should be re-examined, and it should be possible to approach to it from completely different point of view. In other words, if there are essentially CSI organisations which can and in fact do perform CSR, then there are so to say virtues of the wicked, and it is possible for a bad egoistic person to do good for the whole society.

2. CSR Performed by Essentially Criminal and Illegal Businesses

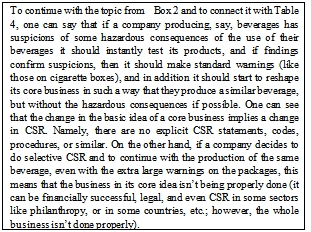

„In times when Las Vegas was governed by mafia there was law & order, now there is neither law, nor order; the town is nowadays obviously less safe then before.“5This statement puzzled me as a philosopher and as a professor of BE & CSR, namely in terms of questioning the basic and by all means common understanding of CSR, and in terms of investigating CSR in some edge/y business sectors. Concerning the issue of understanding, I was puzzled by the conceptual coldness of the very notion of CSR since all or almost all definitions of it imply that the phenomenon itself is positive value impregnated (starting with the simple, basic and common idea that “to be responsible” ex terminis means “to do something substantially good”, while “to be irresponsible” means at least “to omit to do something substantially good”). The essential paradox regarding this conceptual mess and somewhat bizarre examples from Table 2 is the following. Is it or is it not the case that some generally non-legal, criminal, or essentially irresponsible ways of governance are in fact responsible; products are produced, and generally actions are performed in a CSR manner? If such things occur, then essentially irresponsible practices can comprise SR as their proper part or as an aspect. For instance, how should one judge cases when the mafia, by coming from society in return takes care of it in an obviously authentic CSR manner far beyond the scope of its core business; or weapons being properly produced and extremely advertised with extreme care; or when managers in the prostitution industry allow a union to be formed, etc.? In other words, if CSR practices appear in essentially non-CSR business sectors (of dubious morality, being half legal, or criminal), what does this tells us about the very notion of CSR, about its basic ethical background, and about the very nature of typical CSR routines? The previous question splits into a series of particular questions concerning particular cases which can be of some interest for theoretical discussions on CSR as well as for some practical applications of particular CSR measures (some of which are presented in Table 2). In order to illustrate this somewhat abstract question one should mention at least some of the particular and peculiar issues presented in the first part.If answers to questions formulated at the end of the first section are affirmative, then this surely affects our notion of CSR in the following manner: ■ SR is not a positive value impregnated but a morally neutral practice since it can appear in the same way in both basically criminal and basically extremely SR businesses. The notion of responsibility comprises both of facts and values, a kind of mixture in the phenomenon of a standard practice being done properly, or lege artis. And as the consequence of these two, CSR is not something external to the core business but a proper part or an aspect of it, however, not in terms of a basically positive moral motivation for engagement in a business, but rather in terms of understanding and knowing-how to do business properly, which by itself hides CSR and manifests it via any business action being done properly. Namely, in Table 3, the question is - what is the “real” or “practical” difference between, say, the mafia doing CSR beyond the scope of its core business and a legal and essentially responsible business being only selectively CSR? Let us extend the case of 1A (from Table 2) a little bit (as shown in Box 2). Box 2. Mafia are doing authentic CSR

|

| |

|

Now, what ought one say about this particular type of case? There is not much to say about it except that there is a paradox here, namely that essentially criminal business can manifest essentially authentic and integral CSR, while essentially legal businesses can either manifest a complete insensitivity and overall lack of interest and action toward the local community as a relevant stakeholder, or manifest selective CSR – and that, by comparing these two, one can conclude that it is possible for essentially criminal businesses to manifest more CSR then essentially legal businesses, which in its own right creates strange a phenomenon, if not a paradox.An interesting possibility is that in which an essentially illegal business (say the mafia) is being genuinely CSR, meaning far beyond its core business, and an essentially legal business is being selectively CSR, meaning being CSR in one sector while being CSI in another, while it advertises itself as totally CSR. Now, the comparison of these two possibilities by all means shows us that they have legal and financial differences. However, it seems that there are substantial moral differences between them too.6■ This creates the dilemma (if not the paradox) in which an essentially illegal business, while performing without any obvious motive grounded in its core business, can appear more CSR than a legal business being selectively CSR and selectively CSI.However, there are some lessons for understanding CSR generally from these and similar cases, and some of them will be explicated on the following pages.

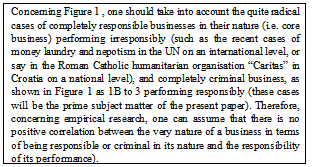

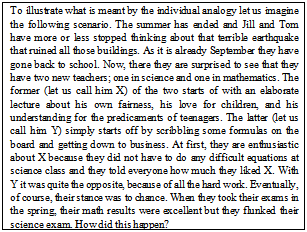

3. Silent Running

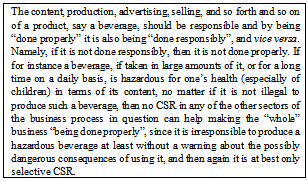

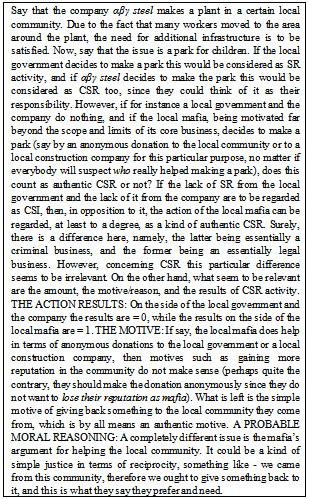

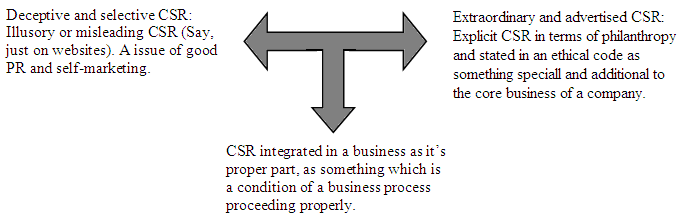

By integral CSR one should not consider something special, extraordinary, or anything like a new “better” concept and practice of CSR (as shown in Table 3 on the right side). ■ Say that we have two companies α and β both of which are legal businesses and are performing their businesses legally. Say that α is doing CSR mainly in terms of philanthropy (donations, sponsorships, corporate giving, etc.) and advertises itself as being CSR, while β is doing CSR mainly in terms of raising and maintaining various standards concerning all relevantly included stakeholder groups (workers, customers, local community, environment, etc.) and doesn’t advertise itself as being CSR. A series of issues can be raised here. How should one compare these two practices and on what grounds? How does one react on advertisements (say TV commercials) of α and β representing themselves as CSR companies? Would private legal persons engage in philanthropy if such donations, charities, etc. (to qualified charitable organisations) would be subject to taxation (that is, not exempted from taxation), and additionally, if such actions would be forbidden to advertise by companies (as a legal person), or by human beings (natural persons) working for it?7 | Figure 2. The place of integral CSR between opposites |

The main feature on integral CSR is that it is an integral part of a business, and therefore, concerning indispensable (paradigm) sections of a business process, no one should advertise it, not even talk about it.8 However, when the paradigm changes, in revolutionary times, issues should be addressed and practical problems solved by certain tools (as shown in Figure 2). Integral CSR can be described via the phenomenon of “silent running” in submarine tactics as a metaphor. Namely, a submarine uses this tactic in order to escape bombs, change its position, and generally to proceed with its actions without making too much noise and fuss about it. It belongs to its core actions.Integral CSR implies many elements which are not so common in its contemporary understanding. For one thing, it implies that there is no sharp difference between functional and substantial goods in any given practical case, or routine practice in a given business. This point implies extensive discussion of the fact-value distinction which cannot be summarised here. However, the critical concept here is “business being done properly or lege artis”. Here some additional semantics is needed. Namely, integral means “holistic” in terms of “understanding a business within the whole of its context” (human, social, environmental, and above all cultural).■ Now, if business (or for that matter any human practice whatsoever) is understood “holistically”, then “business being done properly or lege artis” means that CSR is its integral part and not something which is denied by CSI practices, escaped by illusionary, deceptive, or selective CSR practices, or overdone in terms of explicit and exaggerated CSR by means of ethical codes, ethical bodies, and similar (as shown in Figure 1), and what’s more, that ethical codes or codes of conduct alone do not lower or prevent incidents of corporate illegalities was demonstrated by Mathews’ study ([9], see Box 3).9Box 3. Legal but irresponsible

|

| |

|

However, in contemporary business, issues can pop up on daily basis, or quarterly or annually. Therefore, one should be prepared to explicate an issue, and to find a good solution as quickly as possible. The final issue is how to deal with such problems? Most of the time CSR shouldn’t be discussed at all as far as it does not exceed the scope and limit of discussing business being done properly. Nevertheless, possible risky situations can be predicted, and unpredicted ones can be solved, but the question is how?

4. An Invention Analogy

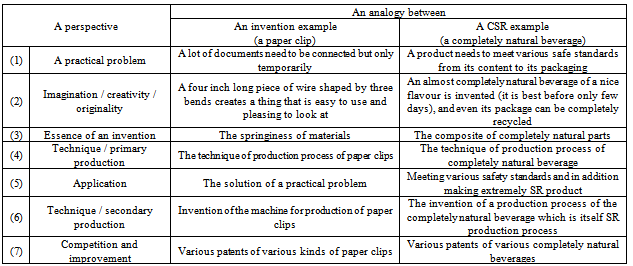

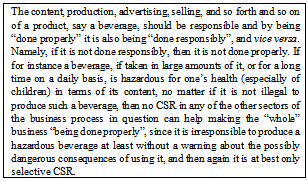

In various textbooks and on the Internet one can find various “key models”, “essential steps”, “standard procedures”, and similar, of solving CSR problems prepared by professors of CSR, people working in various BE centres, by ethical officers in companies, by various governmental agencies, by bodies of experts, various organisations of civic society, NGOs, etc. Such models, or essential steps are generally O.K. but insufficient as well. They lack certain elements which they cannot have by their own nature. For instance imagination, creativity, sensitivity to various viewpoints (cultural, social, and individual) concerning practical problems they try to deal with, knowledge of applying the solution to standard practices, knowledge of the business process itself, etc.In the light of this particular deficit, and as far as it is possible to find an analogy for solving CSR issues (in an integral manner) which can and in fact do pop up, sometimes even without any previous knowledge about them, or even without the prediction of possible dangers, a concept and a procedure of “invention” seems to be a good analogy, since “inventing” implies all the necessary perspectives for a complete, integral, and holistic approach to particular business problems with a that manifest a CSR perspective.Contrary to a structure consisting of models, steps, procedures, keys, and similar, what is suggested here by the use of the “invention” metaphor is simply taking various perspectives by various stakeholders on the problem in question into account. This practice can often manifest not just essential perspectives of the problem, such as financial, legal, and ethical, but many others which are of the utmost value for imagining, and creating practical solutions (here the standard stakeholder theory, its justification, and various applications are presupposed; see[3]). Among such perspectives are the perspectives of production, composition, advertising, selling, using, disposing, and the benefits and costs of a product or a service. As there are such perspectives of a product or a service, there are such perspectives on a problem and its solution concerning a product or a service in question as well. In Table 4 an analogy is drawn between an invention example in terms of the invention of a paper clip and a CSR example in terms of the creation of a final product (say a beverage of natural ingredients)[15].Table 3. An analogy between inventing a paper clip and CSR problem solving in terms of business of producing and selling a completely natural beverage

|

| |

|

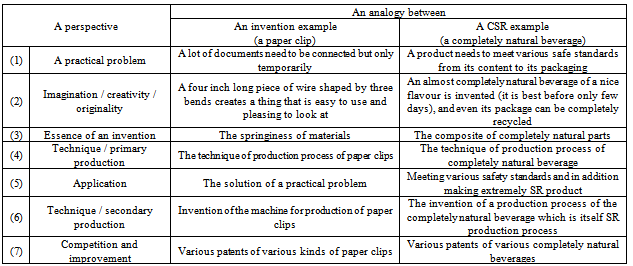

In Table 3, which shows the main perspectives of an invention, patent, and production process in the case of a paper clip, and similar perspectives of an invention, patent and production of a natural beverage, there is no explicit CSR element. However, the very processes have some similarities. What is important to notice is that solving CSR issues is in fact like solving any practical problem by inventing a solution. It needs to be invented simply because the business process is composed of people with their culture, social characteristics, and individual goals. It is all about doing business properly or lege artis. The very process of doing business properly implies and manifests SR of the production process and its application.10However, there are situations in which a standard business process being done properly isn’t enough in order to do it in a SR manner too. In any such case the issue is not the one of making choices between engaging in a risky business (production, meeting safety standards, marketing, etc.), or explicating “special” ethical and CSR standards (which in many cases ends as a selective CSR); rather the thing at issue is a revision of the whole core business idea, and to accommodate it in a way that it corresponds to the idea of doing the whole business properly.Box 4. From possibly irresponsible to responsible by invention

|

| |

|

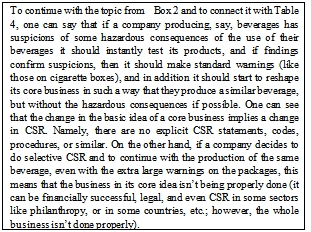

Box 4 presents some kind of ideal case given the present condition of CSR on a global level. However, the revision of a core business, inventing new solutions is a part of the core business (R&D departments). Therefore, the analogy with an invention seems to be fine and helpful. It can be regarded as a part of the basic strategy of a company, but then it implies many changes in the standard structure of governance. What is vital to notice in Box 4 is that there is no explicit mentioning of CSR since it is a part of business being done properly, meaning in a proper way, meaning from the initial motive to do business to the revision of core ideas and procedures. Integral CSR is implicit in the process of a business being done properly and it is essentially manifested by it. On the other hand, if a CSR is advertised by a company it can be the case that it is an issue of selective CSR more likely then the case of an integral CSR, and if a CSI issue appears it can be the consequence of illusory or deceptive CSR (in many cases of CSI one can find that during the time the case was going on a company advertised itself as being CSR and green, people and culture sensitive, and similar; for all the possibilities see Table 4).Table 4. All possibilities between authentic and selective CSR

|

| |

|

■ In such cases one can hardly differ between the selective CSR of such legal businesses and the selective but authentic CSR done by completely illegal businesses (examples of the mafia in Table 2, and in Table 4 the relation between (1) and (2)). No matter if a business is legal or illegal, in both cases there is something wrong with the basic idea of its core business. In order to be an integral CSR business (in Table 4 as (3)), a company needs to revise its core business as much as it is needed due to external influences and internal development (this is in fact a continuous process). Internal development here means to be inventive, creative, and imaginative regarding issues of core business, as well as regarding issues of practical daily problems (from the nature of products and services, to the production process, management and marketing issues). Engaging in external, extraordinary, and additionally advertised CSR is really not necessary. Also, it should be mentioned that if the starting dilemma stands, then we should think of how to reshape the very concept of CSR and this reshaping has to do with the reshaping of our fundamental understanding of business, legality, our societal nature, and our responsibility.

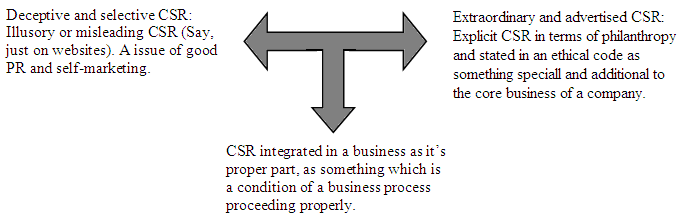

5. An Individual Analogy

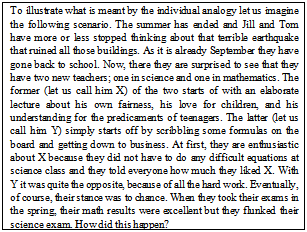

Another way to emphasize the importance of understanding CSR (and by this is meant good, or true CSR) as implicit in core business or as a perspective of core business is by what we may call the “individual” analogy. Besides emphasizing the positive sides of a holistic and integral approach to CSR, it also highlights, in a very vivid way, the negative sides of the explicit and selective CSR approach. In such an analogy CSR will be reduced to simply SR, and CSI to SI.Box 5. The (ir)responsible teachers

|

| |

|

The story in Box 5, or its results can be explicated as following. X is a person who advertises him or herself as highly SR, and in his work, namely that of a teacher, he exercises a selective form of SR, which as the results show clearly, is really nothing more but SI. Y on the other hand understands SR to be an aspect of his work, but one that is such an integral part of a teacher’s job, that doing things SR is simply a part of doing them properly or lege artis. If his students get bad exam results he views that as a result of his not doing his job properly. On the other hand, when X’s students get bad results, he is convinced that it is somehow either their own fault or is simply not explicable. So, at the end of the year, everyone’s favourite teacher is Y, because he is thought to be more SR and even more moral. The point is that we view businesses the same way. The beverage business from Box 4 can advertise itself as CSR and green but when people start getting ill as a result of the long term consummation of their products, they are at once disclosed as being CSI, and perhaps plain immoral. No one wants to have anything to do with such a company, do they?

6. Conclusions

A conclusion can be drawn from this paper by outlining the answer to the question: What have we learned from the mafia example concerning CSR? We have learned the following:1). That from a certain point of view, namely that of integral CSR, a CSR program, though it comes from a legal business, if it is selective and inauthentic, probably contains much CSI, and is therefore irresponsible and probably plain immoral. 2). The only kind of CSR program that really is authentically and non-selectively CSR, and therefore does not contain CSI, is one that is not added to, but contained within the core program of a business. 3). Such a CSR program is not explicit but implicit, being that it is simply an essential part of things “being done properly” or lege artis. 4). If (2) and (3) are not true than there is no criterion for discerning between legal and illegal businesses from a CSR point of view simply because being legal does not logically involve being CSR (as presented in the diagram of Table 3).5). We intuitively choose an integral and holistic CSR model over a non-integral and selective CSR model for businesses just as we a SR and moral individual over an SI and immoral individual (as shown by the example of Box 5). Namely, the “individual” analogy may be showing us that the latter type of CSR produces CSI by its very nature.

Abbreviations

BE = Business EthicsCSR = Corporate Social ResponsibilityCSI = Corporate Social IrresponsibilitySR = Social ResponsibilitySI = Social Irresponsibility

Notes

1. “Corporate crime is any act that is committed by a corporation that is punished by the state, regardless of whether it is punished under administrative, civil, or criminal law.” (Clinard and Yeager, 1980:16) Corporate crime should be differed from white-collar crime since the first is preformed for the benefit of a private legal person, while the second is performed for the benefit of an individual (natural) person or persons. 2. For examples in Table 2, especially in 1A we thank Maria Aluchna from Warsaw School of Economics for describing some Polish examples, and Junko Subota from the Zagreb School of Economics and Management for some examples of Yakuza mafia, namely mister Yamaguchi from Osaka who initiated help for the local community after the earthquake of 1995 in terms of food and shelter, and similar cases in 2006 in northern Japan in Nigata (see Sternhold 1995). Namely, immediately after the Kobe Earthquake of 1995, the Yamaguchi-gumi started a large-scale relief effort for the earthquake victims, helping with the distribution of food and supplies. This help was essential to the Kobe population, because official support was inconsistent and chaotic for several days. In other cases we rely on some Croatian examples, and examples of narcotic cartels in Central and South America, and Italian mafia. However, there is an assortment of approaches by various mafias, some are more CSR, and some are not at all, after all, like legal businesses are as well (we didn’t found any research on comparison of various CSR approaches by different types of criminal organisations). 3. Concerning literature on this topic it should be mentioned that Jean-Pascal Gond, Guido Palazzo, and Kunal Basu in their paper “Investigating Instrumental Corporate Social Responsibility through the Mafia Metaphor” (2007) start from the comparison between legal and criminal organisations as well, namely they follow Gerber (2000) in claiming that there is no fundamental distinction between organised crime and organisational crime. Further on they follow Gambetta (1993), and Morgan (1980), and they claim that the basic similarity between these two is adoption of “instrumental concept of CSR”. However, here it will be argued that there is no problem with instrumental nature of CSR, rather with the lack authenticity and anonymity, and that CSR of legal companies is mainly selective and additionally heavily burdened with the motive of economic and non-economic returns of CSR investments. Examples in 1A in Table 2 don’t imply “giving as a way to obligate stakeholders to engage in reciprocity” (for the see [7], Table 1). 4. Here it is almost impossible even to tackle the issue of fact-value distinction. However, few words should be said. Concerning possibility of deriving “ought” from “is” this particular solution resists to enter the discussion altogether since here it is implied that the difference between facts and values isn’t in kind but in level. For later Wittgenstein (after his “Lecture on Ethics”, i.e. in “Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough”, “Philosophical Investigations” and later works), whose standpoint is presupposed here, it seems that actions are value impregnated and values are action instantiated (this point seems to be consistent with his cultural account of language-games, forms of life, action overviews, and the notion of culture). The emphasis of symbolism, impressiveness, ceremonial nature, and the surroundings of human actions, no matter if these are habitual or extraordinary, contribute to such interpretation. In this particular and somewhat strange manner the fact-value distinction and the problem how to derive ought from is, are overall dismissed, at least for vast majority of standard, routine, and daily practices (see Wittgenstein 1966, 1993, 1998).5. From the discussion with a reliable source (a member of an academic community).6. One can ask a series of questions about the laws that govern and regulate performance of legal companies and even about illegal companies too. For instance, is legal business really legal, what kind of a law about companies is it, is it really morally correct? There are further issues about performance and governance, namely, what does it mean to perform and to do business properly? However, important issue is the one concerning moral and ethical perspective of these actions. If a company isn’t breaking any law by being CSI at some of its sectors and by being CSR in some other sectors, and if does use its CSR to hide its CSI and advertise itself as being completely, authentic, and integrally CSR, then surely the company is doing something dubious. That it does something essentially immoral is obvious when its actions are compared with actions of essentially illegal and criminal organisation which cannot be counted in any other way but as morally correct actions, or at least as less morally incorrect given that the essentially criminal business is in question. 7. Namely, tax incentives permit corporations to deduct from their taxable income the corporate giving that does not exceed 10 percent of pre-tax income. Generally, the level of corporate giving for most US companies has averaged less than 2 percent of pre-tax income. What’s more, and concerning the motive for corporate giving, corporations often engage in philanthropic initiatives in anticipation of economic and non-economic outcomes. (see Smith Coffey 1998:152, Fry, Keim, and Meiners 1982:94-107) 8. Many rich people are famous for their donations to various organisations. However, in Croatia there are many cases of anonymous donations. For instance, few famous sportsmen donated big money to some organisations taking care of physically and mentally challenged persons, and hospitals taking care of seriously ill children. However, they wished to stay anonymous (from a reliable source). Their motives for such actions are beyond discussion, but since some of them run various legal businesses, this can be regarded as authentic and integral CSR by all means. 9. Conceptually speaking, one can understand CSR as an integral part of a business in the similar way as legal requirements of a business are understood. Legal restrictions to businesses have their roots in various sets of tacit or explicated and written rules of conduct at a marketplace. Such rules are considered as an integral part of a business being done properly, and a market functioning properly. Now, given that laws have relevant cultural and therefore moral implications too, a CSR can be understood in the similar way. 10. Paradoxical situation is that we have illegal businesses which can and sometimes indeed are authentically CSR (the case of mafia), legal businesses which by their essential production process cannot be CSR no matter how much they try, such as oil business (and all other dirty businesses), weapon for mass destruction business, and similar, and also legal businesses which are obviously selectively CSR such as marketing in pharmaceutical, food and beverages industries, etc.

References

| [1] | Clinard M. B., Yeager P. C.: 1980, Corporate Crime, New York, Free Press. |

| [2] | Cressey D. R.: 1976, ‘Restraint of trade, recidivism, and delinquent neighbourhoods’, in J. F. Short (ed.) Delinquency, Crime, and Society, Chicago, University of Chicago Press. |

| [3] | Freeman R. Edward: 1984, Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach’, Pitman, Boston. |

| [4] | Fry L. W., Keim G. D., Meiners R. R.: 1982, ‘Corporate Contributions: Altruistic or for profit?’ Academy of management Journal, 25, pp. 94-107. |

| [5] | Gambetta D.: 1993, The Sicilian Mafia. The Business of Private Protection, Cambridge, Harvard University Press. |

| [6] | Gerber J. 2000, ‘On the relationship between organized and white-collar crime’, European journal of Crime, Criminal Law, and Criminal Justice, 8(4), pp. 327-342. |

| [7] | Gond Jean-Pascal, Palazzo Guido, Basu Kunal: 2007, ‘Investigating Instrumental Corporate Social Responsibility through the Mafia Metaphor’, in Research Papers Series, International Centre for CSR, Nottingham University Business School, No. 48-2007 ICCSR Research Paper Series ISSN 1479-5124. |

| [8] | Lampel J.: 2001, ‘Robin Hood’, in Thompson A. A., Strickland A. J. (eds.) Strategic Management Concepts and Cases, McGraw-Hill Irwin, Boston. |

| [9] | Mathews M. C.: 1988 Strategic Intervention in Organisations: Resolving Ethical Dilemmas, Newbury Park, California, Sage. |

| [10] | Morgan G.: 1980, ‘Paradigms, metaphors, and problem solving in organisational theory’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 25(4), pp. 205-622. |

| [11] | Smith Coffey B.: 1998 ‘Corporate Philanthropy’, in Werhane P. and Freeman R. Edward (eds.), Blackwell Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Business Ethics, Blackwell, Oxford, pp. 151-2. |

| [12] | Sternhold, James: 1995 'Quake in Japan: Gangsters, Gang in Kobe Organizes Aid for People In Quake’, Published: January 22, 1995, The New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/1995/01/22/world/quake-in-japan-gangsters-gang-in-kobe-organizes-aid-for-people-in-quake.html (retrieved 9. 7. 2010) |

| [13] | Hård Mikael, Jamison Andrew (eds.): 1998 The Intellectual Appropriation of Technology, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England. |

| [14] | Kottak, Conrad Philip: 1999. Mirror for Humanity, A Concise Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, McGraw-Hill Inc. Boston. |

| [15] | Petroski, Henry: 2000, Invention by design. How Engineers get from Thought to Thing, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England. |

| [16] | Wittgenstein, Ludwig: 1966, Lectures and Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology, and Religious Belief, Blackwell, Oxford. |

| [17] | Wittgenstein, Ludwig: 1993, Remarks on Frazer’s The Golden Bough, in “Philosophical Occasions 1912–1951”, eds. James Klagge and Alfred Nordmann, Indianapolis, IN: Hackett. |

| [18] | Wittgenstein, Ludwig: 1998, Culture and Value, 3rd edition, Oxford: Blackwell. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML