Maliyappanahalli Siddappa Vijayashree, Borlingegowda Viswanatha, Priyadarshini Vincent, Rasika Ravikumar, Nisha Krishna

Bangalore medical college & research institute, Bangalore, India

Correspondence to: Borlingegowda Viswanatha, Bangalore medical college & research institute, Bangalore, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

Neck contains a high density of vital organs in a small unprotected anatomical region, making it a vulnerable part of the body for all type of injuries. Here we present a study on penetrating neck injury done at a tertiary care hospital over a period of seven years. Penetrating neck injuries were found to be high in males (84.27%) between the age group 20 and 40 and majority of incidents of penetrating neck injury (70%) were found in lower socio-economic status. The aetiology of injury is mainly homicidal (50%) followed by suicidal (40%) and accidental (10%). The object used for injury was mainly knife and majority of injuries were found in zone II (64.28%), presenting clinically with wound over the neck breaching platysmal layer. Surgical management included neck exploration, wound debridement and repair in all cases, tracheostomy in 58.57% cases and laryngotracheal repair in 28.57% cases, esophageal repair in 3 cases (4.28%) and pharyngeal repair in 3 cases (4.28%). A proper evaluation, rapid air way intervention and proper surgical repair are essential for a successful outcome. Early management of laryngeal injury within first 24 hours seems to bear the best results for airway and voice. Aggressive surgery is indicated to prevent the complications such as hoarseness, laryngeal stenosis and pharyngeal stenosis.

Keywords:

Penetrating neck injuries, Clinical evaluation, Management

Cite this paper: Maliyappanahalli Siddappa Vijaya, Borlingegowda Viswanatha, Priyadarshini Vincent, Rasika Ravikumar, Nisha Krishna, Clinical Evaluation and Management of Penetrating Neck Injuries, Research in Otolaryngology, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2014, pp. 20-28. doi: 10.5923/j.otolaryn.20140302.03.

1. Introduction

Penetrating neck injuries refer to any injury to the neck in which platysma muscle is breached. It may be induced by wounds of gunshots, stabs and penetrating debris, such as glass or shrapnel. Penetrating neck injury is challenging to treat and the incidence is alarmingly high in recent times mainly because of urban violence, traffic accidents, homicidal and suicidal attempts etc. The injury to the neck resulting in traumatic emergency, where many vital structures are compressed into a compact conduit, demands critical evaluation and treatment. A single penetrating wound is capable of causing considerable harm. Furthermore, seemingly innocuous wounds may not manifest with clear signs or symptoms, and potentially lethal injuries could be easily overlooked. Neck trauma comprises between 5 to 10 per cent of all trauma cases. The mortality rate following neck trauma is as high as 11%, the major vascular injuries being fatal in 65% of cases [1].Various materials can cause penetrating trauma to the neck such as knife, shot gun, sharp instruments, pencils and fragments of glass, blade and metals. These penetrating neck injuries pose a serious threat to vital structures in the neck [2]. Awareness of the various presentations of neck injuries and the establishment of a well-conceived multidisciplinary plan is critical for improving patient outcome, decreasing morbidity and mortality [3]. Expeditious decision making is required to prevent catastrophic aero-digestive, vascular and neurological sequelae. Furthermore, a complete evaluation, rapid airway intervention and proper surgical repair are highly essential to prevent complications [4]. Mandatory surgical exploration remained widely accepted well into the 1990s, when it became obvious that while the mortality rate was low, the rate of negative surgical explorations was unacceptably high (58 percent in one series)[5]. This prospective study on penetrating neck injuries was conducted to elucidate the various presentations, complications and management of penetrating neck injury.

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective study was carried out at Victoria hospital attached to Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, Bangalore. The pertinent data such as proper history, clinical examination, relevant investigations and appropriate management of the neck injuries and its complications were recorded and documented for all the patients presenting with penetrating neck trauma. Patients with trauma due to burns and chemical injuries were excluded from the study. A total of 70 cases of penetrating neck injuries which were treated from 2007 to 2013 were included in this study. The socio-demographic data like age group, sex distribution and socioeconomic status were recorded. The particulars of the insult like type of instrument causing injury and zone of injury were compared. Cases were also clustered according to the etiology of penetrating neck injury and according to structures injured. An analysis of the management of penetrating neck injury with respect to exploration and wound repair and the need for tracheostomy, vascular repair, esophageal repair, laryngeal framework repair and pharyngeal repair was made. The complications of penetrating neck injury such as hoarseness of voice, tracheal stenosis, vocal cord palsy, tracheoesophageal fistula and pharyngeal stenosis, and prognosis of penetrating neck injury to different zones were systematically recorded.The patients were initially examined for airway patency, breathing and adequacy of circulation. Clues to indicate damage to vital structures like breach of platysma, gross bleeding or presence of haematoma (seen in arterial injury), hematemesis, odynophagia, subcutaneous emphysema, blood in saliva or in the aspirate of the nasogastric tube ( seen in indirect aero digestive injuries) etc were looked for. The patients were also examined for symptoms and signs of spinal cord or brachial plexus injury, laryngotracheal injury, signs of carotid artery injury, symptoms and signs of cranial nerve injury, oesophagus and pharynx injury by following standard procedures.The patients were subjected to standard hemotological studies, imaging studies and other supplementary studies. Proper inpatient care, outpatient care and patient education and follow up were ensured.

3. Results

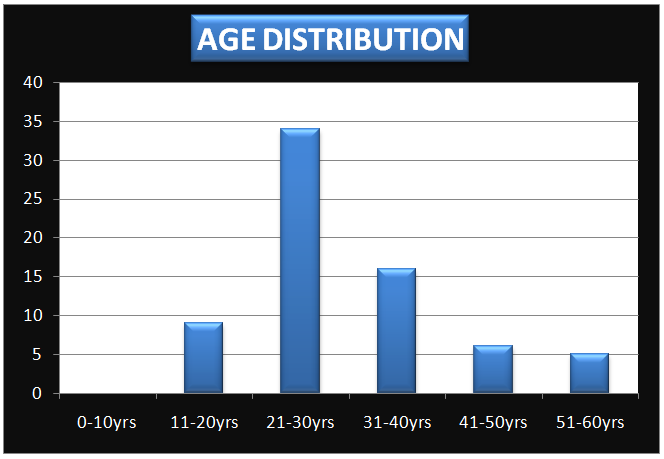

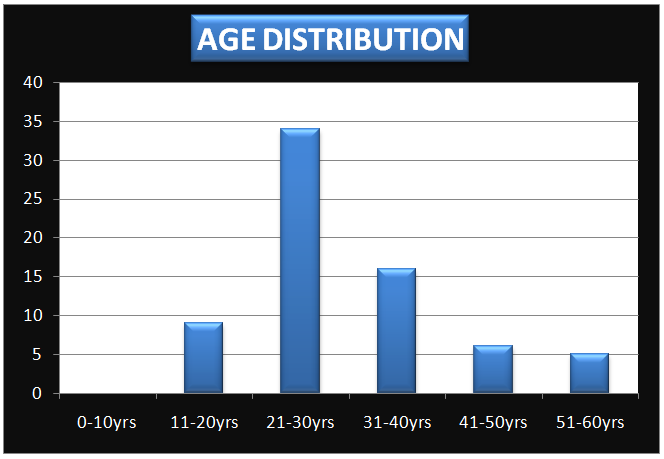

In the present prospective study, 70 patients who presented in casualty with history of neck injury were treated and the results were documented. The age of presentation was between 12 and 55 years with an average age of 33 years. The maximum incidence was observed for the age group between 20 to 30 years. 48.57% of the cases were in the age group 20-30 years and 22.85% were in the age group of 30 to 40 years (table 1 & graph 1). | Table 1. Showing age distribution of cases |

| | Age group | No of cases | Percentage | | 0-10 | 0 | 0 | | 11-20 | 09 | 12.85 % | | 21-30 | 34 | 48.57 % | | 31-40 | 16 | 22.85 % | | 41-50 | 06 | 8.57 % | | 51-60 | 05 | 7.14 % | | Total | 70 | 100.0 % |

|

|

| Graph 1. Showing age distribution of cases |

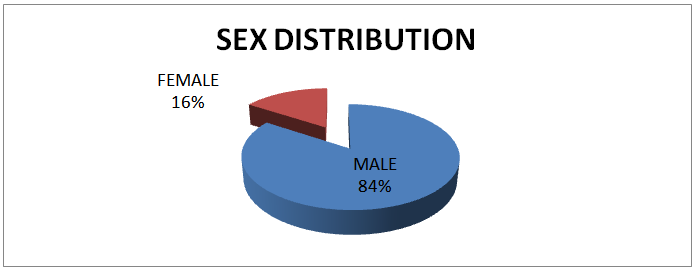

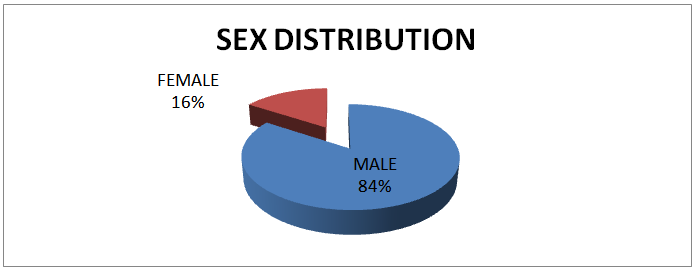

With respect to gender, 84.29% of the cases were males and 15.71% cases were females (table 2 & graph 2). | Table 2. Showing sex distribution of cases |

| | Sex | No of cases | Percentage | | Male | 59 | 84.29% | | Female | 11 | 15.71 % | | Total | 70 | 100.0 % |

|

|

| Graph 2. Showing sex distribution of cases |

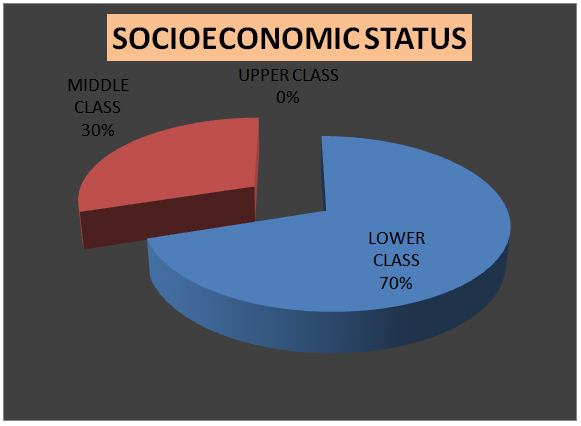

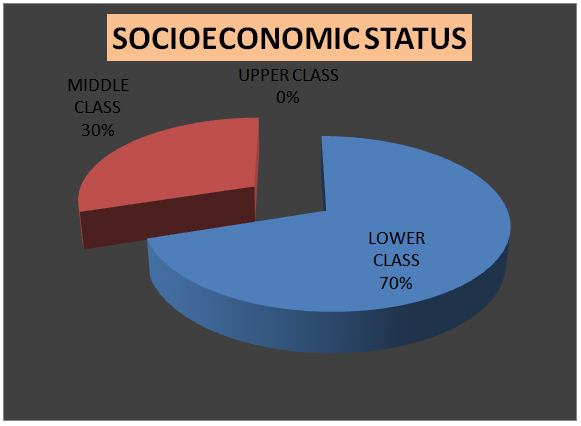

The penetrating neck injuries were found to be more common in low socio-economic group (70.00%) than in middle class group (30.00 %) (table 3 & graph 3). | Table 3. Showing socioeconomic distribution of cases |

| | Socioeconomic status | No of cases | Percentage | | Lower class | 49 | 70.00 % | | Middle class | 21 | 30.00 % | | Upper class | 0 | 0.0 % | | Total | 70 | 100.0 % |

|

|

| Graph 3. Showing socioeconomic distribution of cases |

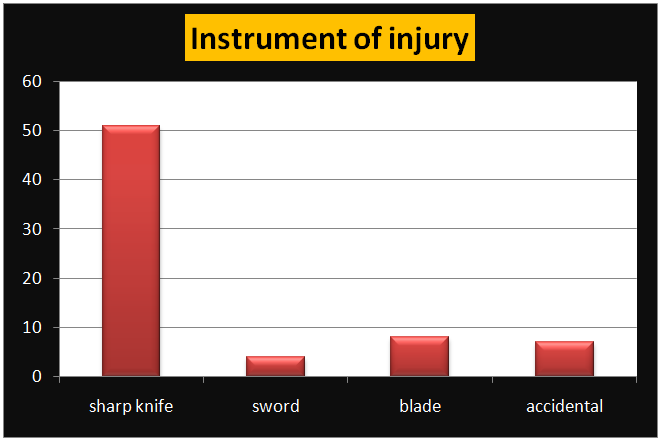

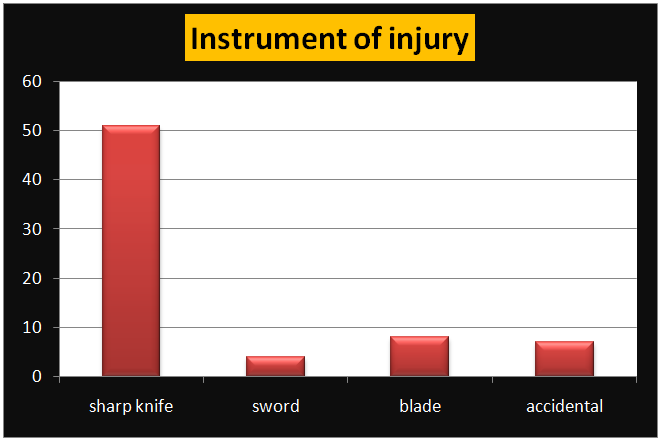

It was revealed from the study that, the object causing the maximum number of neck injuries was knife, in 51 cases (72.85%), followed by razor blade in 8 cases (11.43%), sword in 4 cases (05.71%,) and 7 cases (10%) were due to accidents. In majority of the cases, knife was used in homicidal injuries and razor blade was used in suicidal injuries (table 4 & graph 4).| Table 4. Showing type of instrument causing injury |

| | Instrument | No of cases | Percentage | | Sharp knife | 51 | 72.85 % | | Sword | 04 | 05.71 % | | Blade | 08 | 11.43% | | Accidental | 07 | 10.0 % | | Total | 70 | 100.0 % |

|

|

| Graph 4. Showing type of instrument causing injury |

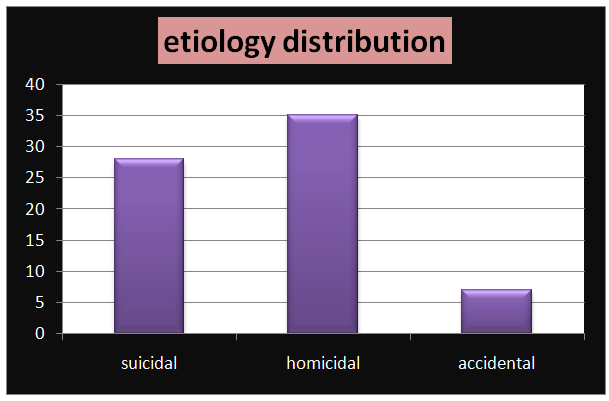

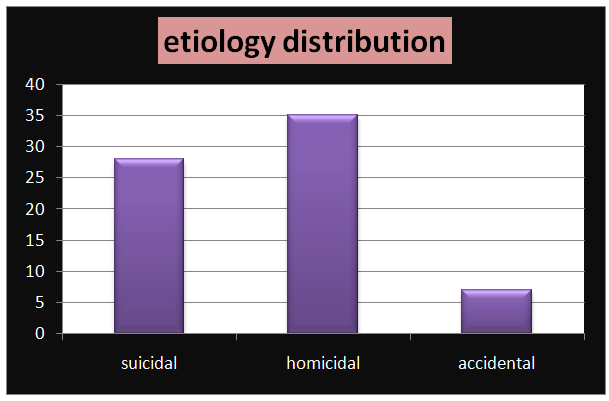

It was also observed that, 35 cases (50.0%) were homicidal, 28 cases (40.0%) were suicidal and 7 cases (10%) were accidental (table 5 & graph 5). | Table 5. Showing etiological Distribution of total cases |

| | Etiology | No of cases | Percentage | | Suicidal | 28 | 40.0 % | | Homicidal | 35 | 50.0 % | | Accidental | 07 | 10.0 % | | Total | 70 | 100.0 % |

|

|

| Graph 5. Showing etiological Distribution of total cases |

The distribution of cases according to zone of injury revealed that the zone II was most commonly affected with 64.28 % injuries, followed by zone I and zone III with 18.57 % and 17.14 % respectively (table 6).| Table 6. Showing distribution of cases according to zone of injury |

| | Diagnosis | No. of cases | Percentage | | Zone I | 13 | 18.57% | | Zone II | 45 | 64.28% | | Zone III | 12 | 17.14% | | Total | 70 | 100.0% |

|

|

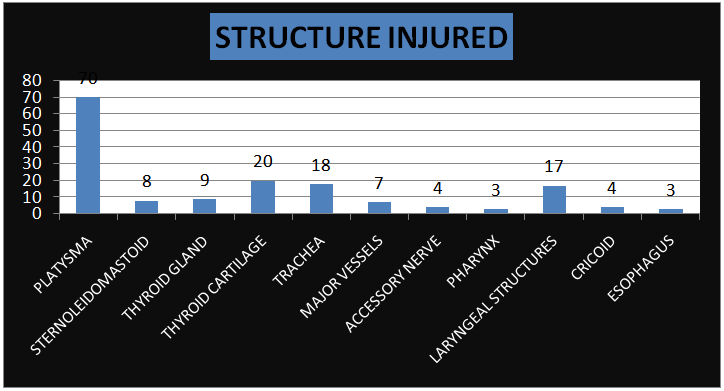

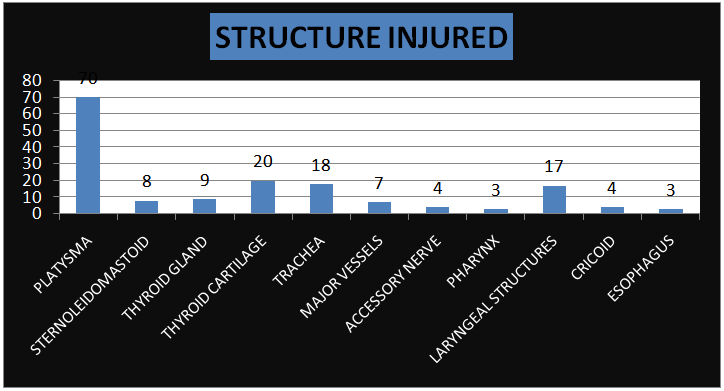

The structures injured in the study indicated that platysma was involved in all the cases, thyroid cartilage in 20, trachea in 18, laryngeal structures in 17, thyroid gland in 9, sternocleidomastoid in 8, major vessels in 7, accessory nerve and cricoid cartilage in 4 and pharynx and oesophagus in 3 cases. (table 7 & graph 6). | Table 7. Showing distribution of cases according to structures injured |

| | Structure injured | No of cases | Percentage | | Platysma | 70 | 100 % | | sternocleidomatoid | 08 | 11.43 % | | Thyroid gland | 09 | 12.86 % | | Thyroid cartilage | 20 | 28.57 % | | Trachea | 18 | 25.71 % | | Major vessels | 07 | 10.00 % | | Accessory nerve | 04 | 5.71 % | | Pharynx | 03 | 4.28 % | | Laryngeal structures | 17 | 24.28 % | | Cricoid cartilage | 04 | 5.71 % | | Esophagus | 03 | 4.28 % |

|

|

| Graph 6. Showing distribution of cases according to structures injured |

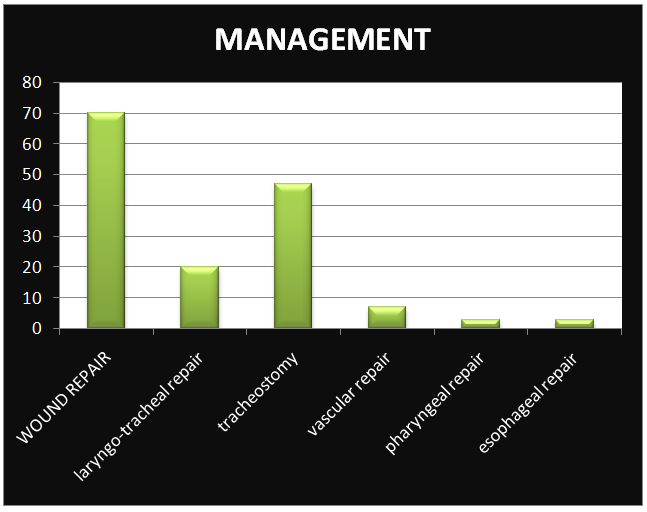

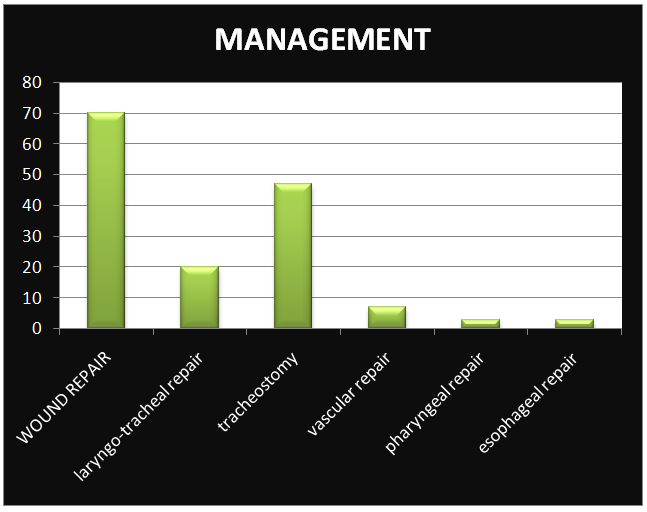

In the present study wound exploration and repair was done in all cases (100%) while, laryngeal repair in 20 cases (28.57%), tracheostomy in 47 cases (58.57%) [Figure 1], vascular repair in 7 cases, oesophageal repair in 3 cases (4.28 %) and pharyngeal repair in 3 cases (4.28 %) (Table 8 & graph 7). | Figure 1. Photograph showing healed neck wound and tracheostomy opening |

| Table 8. Showing management of penetrating neck injury |

| | Surgical repair | No of cases | Percentage | | Wound repair | 70 | 100% | | Laryngotracheal repair | 20 | 28.57% | | Tracheostomy | 47 | 58.57 % | | Vascular repair | 07 | 10.00 % | | Pharyngeal repair | 03 | 4.28 % | | Esophageal repair | 03 | 4.28 % |

|

|

| Graph 7. Showing management of penetrating neck injury |

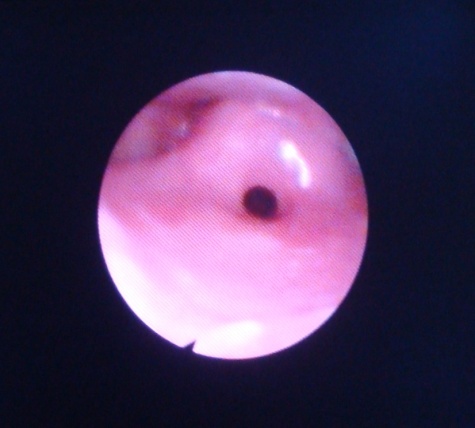

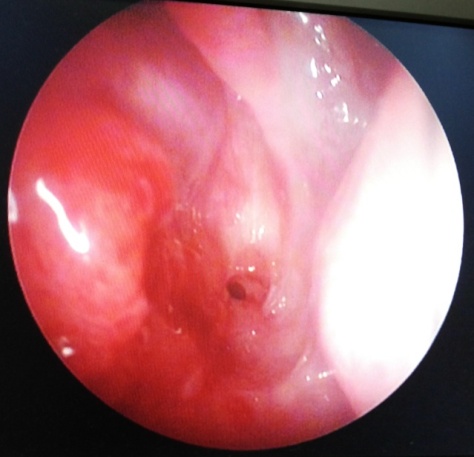

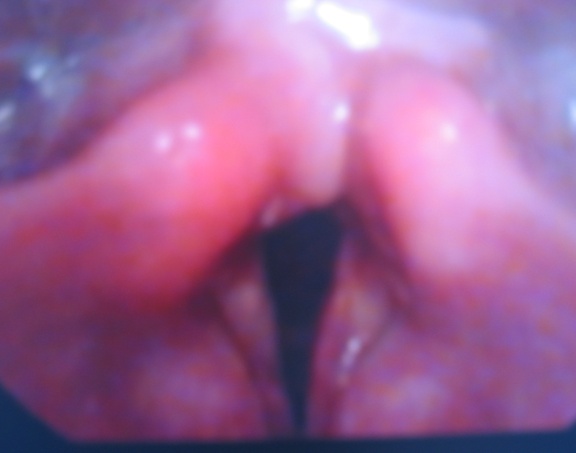

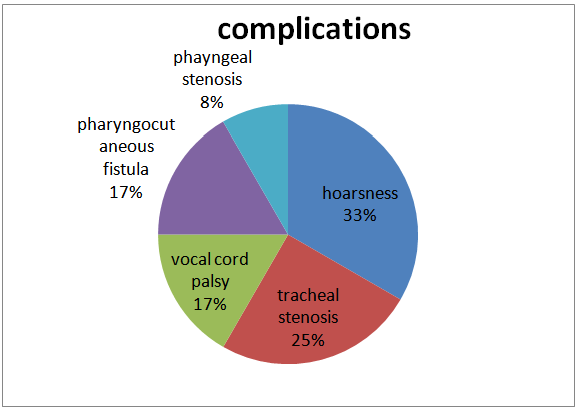

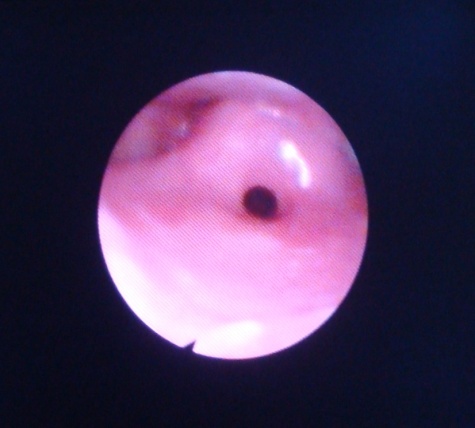

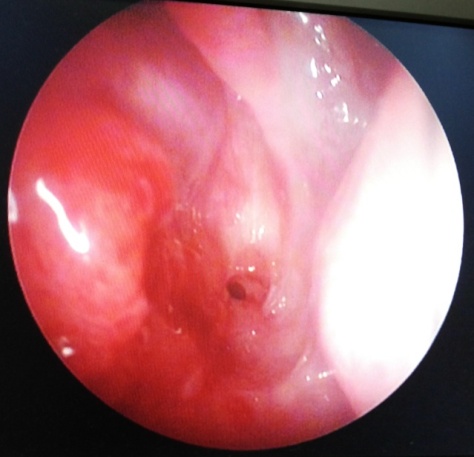

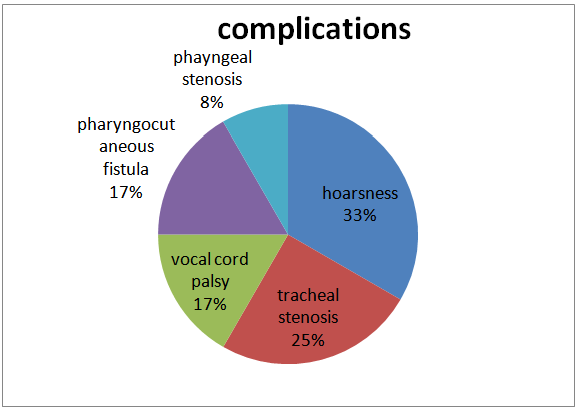

In our study, 11 patients had developed complications (15.71%), of which 4 cases developed hoarseness of voice (5.71%), 3 cases developed tracheal stenosis (4.28%) [Figure 2], two patients each developed pharyngocutaneous fistula (2.85%), one patient developed pharyngeal stenosis (1.42%) [Figure 3] and two patients (2.85%) had vocal cord palsy [figure 4] (table 9 & graph 8). | Figure 2. Photograph showing endoscopic view of tracheal stenosis and arytenoids swellings |

| Figure 3. Photograph showing endoscopic view of pharyngeal stenosis |

| Figure 4. Photograph showing endoscopic view of left vocal cord palsy |

| Table 9. Showing complications of penetrating neck injury |

| | Complication | No of cases | Percentage | | Hoarseness voice | 04 | 5.71 % | | Tracheal stenosis | 03 | 4.28 % | | Vocal cord palsy | 02 | 2.85 % | | Pharyngocutaneous fistula | 02 | 2.85 % | | Pharyngeal stenosis | 01 | 1.42 % | | Total | 11 | 15.71% |

|

|

| Graph 8. Showing complications of penetrating neck injury |

In the present study, out of 70 cases, 2 cases (2.86%) resulted in death due to accidental injury (table 10).| Table 10. Showing prognosis of penetrating neck injury |

| | Zones | No of cases | No of deaths | | Zone I | 16 | 1 | | Zone II | 44 | 1 | | Zone III | 10 | 0 |

|

|

All the cases were treated with neck exploration, wound debridement with repair and closure of wound in layers. Tetanus toxoid prophylaxis, anti-inflammatory and antibiotics were given as remedy to cure the infections.

4. Discussion

In the present study, the maximum incidence of penetrating neck injury was observed in the age group between 20 to 30 years. 48.57 % of the cases were in the age group 20-30 years and 22.86% were in the age group of 30 to 40 years. This indicates that young people are more prone to neck injuries, perhaps due to their indulgence in homicidal and suicidal act owing to their poor psychological and financial condition. In a case series in 2007, reported mean age of incidence was 32 years [4]. With respect to gender, 84.29% of the cases were males and 15.71% cases were females. The penetrating neck injuries were found to be more common in low socio-economic group (70.00%) than in middle class group (30.00%), again the reasons being their indulgence in homicidal act due to growing conflicts and poor psychological and financial condition. Jeffrey et al [6] in 1995 reported penetrating neck injury in 87% males and 13% females, the incidence being almost equal to our study. Our study also showed that, the object that caused maximum number of neck injuries was knife (in 51 cases) (72.85%) followed by razor blade in 8 cases (11.43%). In majority of the cases knife was used in homicidal injuries and razor blade was used in suicidal injuries. A study by Nason et al [7] in 2001 reported that injuries were due to knife in 60%, broken glass in 12.3%, and blade in 15% cases.It was also observed that, 35 cases (50.0%) were homicidal, 28 cases (40.0%) were suicidal and 7 cases (10%) were accidental. It was common in urban slum dwellers. Suicides were more commonly seen in middle class group and homicides were seen more in low socio-economic group.Penetrating neck injuries are usually described in terms of their location in one of three anatomic zones as described by Monson [8, 9].Zone I is the region that extends from the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage to the clavicle. Injuries in this region carry a high mortality risk because they involve the thoracic structures, major vessels, upper mediastinum, lungs, trachea, esophagus, and thoracic duct, and also because surgical exposure is difficult.Zone II is the area between the cricoid cartilage and the angle of the mandible. This is the most frequently injured region of the neck but the mortality rate from these injuries is relatively low because of better surgical exposure compared to other zones. Underlying structures are the major arteries and veins of the neck, the air and food passages, the cervical spine and the thyroid gland.Zone III comprises the area between the angle of the mandible and the base of the skull. Wounds in this region are most commonly associated with vascular and pharyngeal injuries. As in zone I, surgical exposure is difficult in this area.Although zones I and III are protected by bones, penetrating trauma of these area is more dangerous than in zone II because of proximity of thorax and skull base. The vital structures in the zone II are not protected by bone, and the risk of injury is different to that in zone I and III [1].The distribution of cases according to zone of injury revealed that the zone II was most affected with 64.28% injuries, followed by zone I and zone III with 18.58 % and 17.14 % respectively. Viswanatha et al [4] reported 14.2% injuries in zone I, 80% injuries in zone II and 4.7% injuries in zone III, and Nason et al [7] reported 15% injuries in zone I, 81% injuries in zone II and 4% injuries in zone III.Multiple vital structures of the neck which are vulnerable to injury can be divided into four groups [1]:(i) The air passages: trachea, larynx and lung;(ii) Vascular structures: carotid, jugular, subclavian, innominate and aortic arch vessels;(iii) Gastrointestinal structures: pharynx and oesophagus; and(iv) Neurological structures: cranial nerves, peripheral nerves, brachial plexus and spinal cord.Types of injury and associated findings can be classified as follows [1, 10]:a. Findings suggestive of air way injury: Common signs of laryngeal injury include stridor, subcutaneous emphysema, haemoptysis, hematoma, ecchymosis, laryngeal tenderness, vocal cord immobility, loss of anatomical landmarks, and crepitus. Other findings may include fracture of the hyoid bone, widening of the thyrohyoid membrane, displaced fractures of the thyroid cartilage, fracture of the cricoid cartilage, and separation of the cricoid cartilage from the larynx or trachea.b. Findings suggestive of pharyngo-oesophageal injury: dysphagia, soft tissue crepitus, widening of retropharyngeal space.c. Findings suggestive of vascular injury: expanding haematoma, thrills and bruits, hypovolemic shock, persistent haemorrhage.d. Neurologic injury: hoarseness, cranial nerves deficits,The structures injured in the study indicated that platysma was involved in all the cases, thyroid cartilage in 20, trachea in 18, laryngeal structures in 17, thyroid gland in 9, sternocleidomastoid in 8, major vessels in 7, accessory nerve and cricoid cartilage in 4 and pharynx and oesophagus in 3 cases. Nason et al [7] had reported vascular injury in 9.2% pharynx and oesophageal injury in 6.9%.Evaluation of laryngeal trauma begins with ensuring a patent airway. There is no uniform agreement as to the preferred method of airway management in patients with penetrating neck injuries. The preferred artificial airway in patients with laryngeal injuries is a tracheostomy, which should be performed with the patient awake under local anesthesia if possible. Associated cervical spine, oesophageal, and vascular injuries can then be evaluated. Most authors agree that blind intubation methods (i.e. blind nasotracheal intubation) should not be used in these patients because further injury or complete airway obstruction may be induced. A blind attempt at intubating the trachea may carry the risk of introducing the tracheal tube into a false passage or cause a complete disruption of the endolaryngeal structures, or even facilitating laryngo-tracheal separation. The incidence of these phenomena is unknown but is most likely lethal and difficult to reverse even with an emergency surgical airway [1, 11]. The wound exploration and repair was done in all cases (100%) while, laryngeal repair in 20 cases (28.57%), tracheostomy in 47 cases (58.57%), vascular repair in 7 cases. Jeffery et al [6] reported that laryngeal repair was required in 31% of cases and airway repair was required in 37% of cases Nason et al [7].The complications of anterior neck injuries are classified as immediate, intermediate and delayed [12-19]. They are as follows;Immediate complications:1. Respiratory obstruction from: a) Fractured hyoid bone, thyroid, cricoid or tracheal cartilages pushed posteriorly.

a) Fractured hyoid bone, thyroid, cricoid or tracheal cartilages pushed posteriorly. b) Slit base of tongue falling over the laryngeal inlet.

b) Slit base of tongue falling over the laryngeal inlet. c) Oedema or haematoma in or around the larynx.

c) Oedema or haematoma in or around the larynx. d) Flooding of the air passages and patient drowning in his blood.2. Air aspiration into the neck veins and embolization3. Profuse haemorrhage and hypovolemic shock.Intermediate complications:1. Respiratory obstruction due to surgical emphysema2. Non-specific infections like cervical cellulitis, perichondritis, and anterior mediastinitis.3. Tetanus and gas gangrene in contaminated wounds.4. Aspiration pneumonitis due to loss of laryngeal afferents or motor control in the protective cough reflex or tracheo-esophageal fistula.5. Pharyngo-cutaneous or trachea-oesophageal fistula.6. Chyle or lymph fistula.Delayed complications:1. Aphonia, dysphonia or hoarseness2. Stenosis of the aero digestive tract.3. Aneurysmal formation or arterio-venous fistula.4 Hypertrophic neck scars.5. Psychological traumaIn our study 11 patients had developed complications (15.71%) where, 4 patients developed hoarseness of voice (5.71%), 3 cases developed tracheal stenosis (4.28%), two patients each developed pharyngocutaneous fistula (2.85%) and one patient developed pharyngeal stenosis (1.42%). In a study by Nason et al [7] 11 patients developed complications (15.71%) of which, 4 patients had hoarseness of voice (5.71%) and 3 cases developed tracheal stenosis (4.28%). Bumpous et al [20] reported hoarseness of voice in 13% of cases and expanding haematoma in 6% of cases. Similarly, the incidence of vocal cord palsy was 14.2% and incidence of tracheal stenosis was 4.7% patients as reported by Viswanatha et al [4]. Also, a mortality rate of 2.86% is reported in the present study, due to accidental injury which is comparable with the reports of mortality rate of 8.3% and 13% respectively by Jeffery et al & Nason et al [6, 7].Laryngeal mucosal lacerations from penetrating injury should be repaired early (within 24 hours). Significant glottic and supra glottic lacerations and displaced cartilage fractures need surgical approximation. In a study Leopold [21] found that the time elapsed before repair has an effect on both airway stenosis and on voice.The psychiatric monitoring of the accused in case of homicide or the patient himself in cases of suicide is a must [12].

d) Flooding of the air passages and patient drowning in his blood.2. Air aspiration into the neck veins and embolization3. Profuse haemorrhage and hypovolemic shock.Intermediate complications:1. Respiratory obstruction due to surgical emphysema2. Non-specific infections like cervical cellulitis, perichondritis, and anterior mediastinitis.3. Tetanus and gas gangrene in contaminated wounds.4. Aspiration pneumonitis due to loss of laryngeal afferents or motor control in the protective cough reflex or tracheo-esophageal fistula.5. Pharyngo-cutaneous or trachea-oesophageal fistula.6. Chyle or lymph fistula.Delayed complications:1. Aphonia, dysphonia or hoarseness2. Stenosis of the aero digestive tract.3. Aneurysmal formation or arterio-venous fistula.4 Hypertrophic neck scars.5. Psychological traumaIn our study 11 patients had developed complications (15.71%) where, 4 patients developed hoarseness of voice (5.71%), 3 cases developed tracheal stenosis (4.28%), two patients each developed pharyngocutaneous fistula (2.85%) and one patient developed pharyngeal stenosis (1.42%). In a study by Nason et al [7] 11 patients developed complications (15.71%) of which, 4 patients had hoarseness of voice (5.71%) and 3 cases developed tracheal stenosis (4.28%). Bumpous et al [20] reported hoarseness of voice in 13% of cases and expanding haematoma in 6% of cases. Similarly, the incidence of vocal cord palsy was 14.2% and incidence of tracheal stenosis was 4.7% patients as reported by Viswanatha et al [4]. Also, a mortality rate of 2.86% is reported in the present study, due to accidental injury which is comparable with the reports of mortality rate of 8.3% and 13% respectively by Jeffery et al & Nason et al [6, 7].Laryngeal mucosal lacerations from penetrating injury should be repaired early (within 24 hours). Significant glottic and supra glottic lacerations and displaced cartilage fractures need surgical approximation. In a study Leopold [21] found that the time elapsed before repair has an effect on both airway stenosis and on voice.The psychiatric monitoring of the accused in case of homicide or the patient himself in cases of suicide is a must [12].

5. Conclusions

All penetrating neck injuries are potentially dangerous and require emergency treatment because of the presence of important vessels, nerves and organs in the neck. Risk of significant injury to vital structures in the neck is dependent on the type of penetrating object. Thorough knowledge of the anatomy of neck, clinical assessment and diagnostic and therapeutic interventions are necessary for appropriate management.

References

| [1] | Ozturk K, Keles B, Cenik Z and Yaman H. Penetrating zone II neck injury by broken windshield. Int. Wound J. 2006 Mar. 3(1):63-66. |

| [2] | Godbole BG, Vira TM, Rao RV. Stab injury of neck (a case report). J Postgrad Med. 1980 Oct. 26(4):257-258. |

| [3] | Demetriades D, Theodorou D, Cornwell E. Evaluation of penetrating injuries of the neck: prospective study of 223 patients. World J. Surg. 1997: 41-48. |

| [4] | Vishwanatha B, Sagayraj A, Shalini GH, Prashanthkumar, Datta RK. Penetrating neck injuries. Ind. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surgery. 2007 July-Sept.59:221-224. |

| [5] | Apffelstaedt JP, Müller R. Results of mandatory exploration for penetrating neck trauma. World J. Surg. 1994 Nov-Dec. 18 (6):917-918. |

| [6] | Jeffrey GJ, Gordon RP III, William SC, Sanford SJ, Robert IG. Penetrating Neck Trauma: Sensitivity of Clinical Examination and Cost-effectiveness of Angiography AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1995 April. 16:647–654. |

| [7] | Nason RW, Assuras GN, Gray PR, Lipschitz J, Burns CM. Penetrating neck injuries: Analysis of experience from a Canadian trauma centre. Can. J. Surg. 2001 April. 44(2):122-126. |

| [8] | Bardley J Phillips (2002.) The penetrating neck wound: A few points. The internet journal of surgery. 3 (2). |

| [9] | Desjardins G and Varon AJ (2001) Airway management for penetrating neck injuries: the Miami experience. Resuscitation 48:71–75. |

| [10] | Mandavia DP, Qualls S and Ivan (2000) Emergency airway management in penetrating neck injury. Annals of emergency medicine 35:221–225. |

| [11] | Verschueren DS, Bell RB, Bagheri SC, Dierks EJ and Potter BE (2006) Management of laryngo- tracheal injuries associated with craniomaxillofacial trauma. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 64:203–214. |

| [12] | Chandrakant, Vishwambharsingh, Choudhary, Tiwari. Online otolaryngology journal. Volume 3 Issue 4 2013, 145-162. |

| [13] | VivekSasindran, Antony Joseph: management of penetrating zone II neck injuries. Indian Journal Of Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. (October-December) 2009:61:313-316. |

| [14] | AbhaySinha, Savitri Gupta: Computed Tomography in the evaluation of Laryngotracheal Stenosis. Indian Journal Of Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. (april-june) 2004:56: 104-107. |

| [15] | Ladapo AA: Open injuries of anterior aspect of the neck. Ghana Med Journal 1979:4:182-6. |

| [16] | Kendall JL, Anglin D, Demetriades D. Penetrating neck trauma.Emergency Medicine Clinics ofNorth America 1998; 16:85-105. |

| [17] | Biffl WL, Moore EE, Rehse DH, Offner PJ, Franciose RJ, Burch JM. Selective management of penetrating neck trauma based on cervical level of injury. American Journal of Surgery 1997; 174:678-82. |

| [18] | Demetriades D, Asensio JA, Velmahos G, Thal E. Complex problems in penetrating neck trauma. Surgical Clinics of North America1996;76:661-83. |

| [19] | Spunt B, Goldstein P, Brownstein H, FendrickM.The role of marijuana inhomicide. InternationalJournal of the addictions 1994;29(2):195-213. |

| [20] | Bumpous JM, Whitt PD, Ganzel TM, McClane SD. Penetrating injuries of the visceral compartment of the neck. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2000 May-Jun. 21(3):190-194. |

| [21] | Leopold DA (1983) Laryngeal trauma: A historical comparison of treatment methods. Arch Otolaryngol 109: 106–110. |

a) Fractured hyoid bone, thyroid, cricoid or tracheal cartilages pushed posteriorly.

a) Fractured hyoid bone, thyroid, cricoid or tracheal cartilages pushed posteriorly. b) Slit base of tongue falling over the laryngeal inlet.

b) Slit base of tongue falling over the laryngeal inlet. c) Oedema or haematoma in or around the larynx.

c) Oedema or haematoma in or around the larynx. d) Flooding of the air passages and patient drowning in his blood.2. Air aspiration into the neck veins and embolization3. Profuse haemorrhage and hypovolemic shock.Intermediate complications:1. Respiratory obstruction due to surgical emphysema2. Non-specific infections like cervical cellulitis, perichondritis, and anterior mediastinitis.3. Tetanus and gas gangrene in contaminated wounds.4. Aspiration pneumonitis due to loss of laryngeal afferents or motor control in the protective cough reflex or tracheo-esophageal fistula.5. Pharyngo-cutaneous or trachea-oesophageal fistula.6. Chyle or lymph fistula.Delayed complications:1. Aphonia, dysphonia or hoarseness2. Stenosis of the aero digestive tract.3. Aneurysmal formation or arterio-venous fistula.4 Hypertrophic neck scars.5. Psychological traumaIn our study 11 patients had developed complications (15.71%) where, 4 patients developed hoarseness of voice (5.71%), 3 cases developed tracheal stenosis (4.28%), two patients each developed pharyngocutaneous fistula (2.85%) and one patient developed pharyngeal stenosis (1.42%). In a study by Nason et al [7] 11 patients developed complications (15.71%) of which, 4 patients had hoarseness of voice (5.71%) and 3 cases developed tracheal stenosis (4.28%). Bumpous et al [20] reported hoarseness of voice in 13% of cases and expanding haematoma in 6% of cases. Similarly, the incidence of vocal cord palsy was 14.2% and incidence of tracheal stenosis was 4.7% patients as reported by Viswanatha et al [4]. Also, a mortality rate of 2.86% is reported in the present study, due to accidental injury which is comparable with the reports of mortality rate of 8.3% and 13% respectively by Jeffery et al & Nason et al [6, 7].Laryngeal mucosal lacerations from penetrating injury should be repaired early (within 24 hours). Significant glottic and supra glottic lacerations and displaced cartilage fractures need surgical approximation. In a study Leopold [21] found that the time elapsed before repair has an effect on both airway stenosis and on voice.The psychiatric monitoring of the accused in case of homicide or the patient himself in cases of suicide is a must [12].

d) Flooding of the air passages and patient drowning in his blood.2. Air aspiration into the neck veins and embolization3. Profuse haemorrhage and hypovolemic shock.Intermediate complications:1. Respiratory obstruction due to surgical emphysema2. Non-specific infections like cervical cellulitis, perichondritis, and anterior mediastinitis.3. Tetanus and gas gangrene in contaminated wounds.4. Aspiration pneumonitis due to loss of laryngeal afferents or motor control in the protective cough reflex or tracheo-esophageal fistula.5. Pharyngo-cutaneous or trachea-oesophageal fistula.6. Chyle or lymph fistula.Delayed complications:1. Aphonia, dysphonia or hoarseness2. Stenosis of the aero digestive tract.3. Aneurysmal formation or arterio-venous fistula.4 Hypertrophic neck scars.5. Psychological traumaIn our study 11 patients had developed complications (15.71%) where, 4 patients developed hoarseness of voice (5.71%), 3 cases developed tracheal stenosis (4.28%), two patients each developed pharyngocutaneous fistula (2.85%) and one patient developed pharyngeal stenosis (1.42%). In a study by Nason et al [7] 11 patients developed complications (15.71%) of which, 4 patients had hoarseness of voice (5.71%) and 3 cases developed tracheal stenosis (4.28%). Bumpous et al [20] reported hoarseness of voice in 13% of cases and expanding haematoma in 6% of cases. Similarly, the incidence of vocal cord palsy was 14.2% and incidence of tracheal stenosis was 4.7% patients as reported by Viswanatha et al [4]. Also, a mortality rate of 2.86% is reported in the present study, due to accidental injury which is comparable with the reports of mortality rate of 8.3% and 13% respectively by Jeffery et al & Nason et al [6, 7].Laryngeal mucosal lacerations from penetrating injury should be repaired early (within 24 hours). Significant glottic and supra glottic lacerations and displaced cartilage fractures need surgical approximation. In a study Leopold [21] found that the time elapsed before repair has an effect on both airway stenosis and on voice.The psychiatric monitoring of the accused in case of homicide or the patient himself in cases of suicide is a must [12]. Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML