-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Otolaryngology

p-ISSN: 2326-1307 e-ISSN: 2326-1323

2014; 3(2): 16-19

doi:10.5923/j.otolaryn.20140302.02

A Unique Case of Invasive Fungal Sinusitis Mimicking Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis

Borlingegowda Viswanatha, Maliyappanahalli Siddappa Vijayashree, Mary Bibiana Harsha, Santhosh Kumar Prabhakar, Glen Edwin D’Souza, Nisha Krishna

Bangalore medical college & research institute, Bangalore, India

Correspondence to: Borlingegowda Viswanatha, Bangalore medical college & research institute, Bangalore, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is one of the less frequent forms of fungal rhinosinusitis. It occurs in immunocompromised patients (AIDS, hematologic diseases, type 1 diabetes mellitus) with a fatal outcome if not treated. We report a case of an unusual presentation of invasive fungal sinusitis in which a 40yr old male diabetic patient presented to us primarily with ophthalmic symptoms without nasal symptoms, suggestive of cavernous sinus thrombosis. This paper emphasizes the need for the clinicians to keep this diagnosis in mind when managing an immunocompromised patient presenting with ocular symptoms or cranial nerve palsies, as in such cases, early diagnosis may be the most important step in successful treatment of the patient.

Keywords: Invasive fungal sinusitis, Cavernous sinus, Thrombosis

Cite this paper: Borlingegowda Viswanatha, Maliyappanahalli Siddappa Vijaya, Mary Bibiana Harsha, Santhosh Kumar Prabhakar, Glen Edwin D’Souza, Nisha Krishna, A Unique Case of Invasive Fungal Sinusitis Mimicking Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis, Research in Otolaryngology, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2014, pp. 16-19. doi: 10.5923/j.otolaryn.20140302.02.

1. Introduction

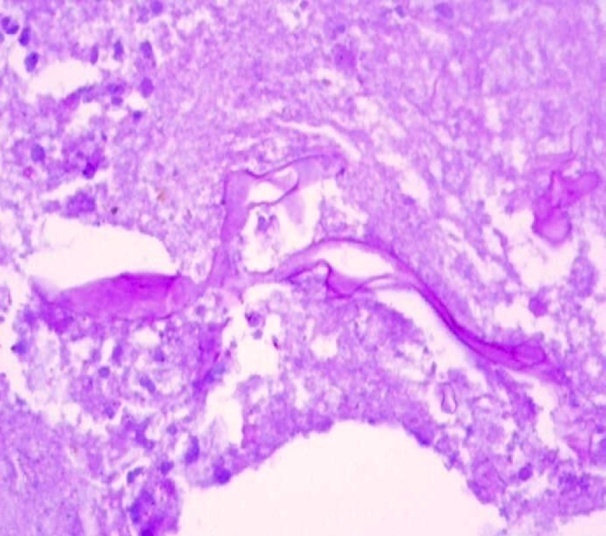

- Invasive fungal sinusitis is characterized by a mycotic infiltration of the mucous membrane of the nasal cavity and/or the paranasal sinuses. It occurs commonly in immunocompromised patients. The initial symptoms tend to be subtle, even in at-risk patients. The most common presenting symptoms of patients with invasive fungal sinusitis as documented in a recent study were facial swelling (64.5%), fever (62.9%), and nasal congestion (52.2%) [1]. Direct orbital extension is generally indicated by pain, proptosis, ophthalmoplegia or trigeminal nerve sensory loss. It involves the nasal cavity, sinuses, eyes, and then the brain. It can be further complicated by seizures, hemiplegia and coma. It can be associated with necrosis of the palate and nasal mucosa. Nasal ulcerations occur in 38 to 74% of the patients with painful black eschar on the palate or nasal mucosa, which is considered a classical but nonspecific sign [2, 3]. The most frequent sites of involvement are near the middle turbinate, the septum and more rarely the inferior turbinate [4]. Mucoraceae and Aspergillus are some of the frequently isolated fungi. They appear to have a marked predilection for vascular invasion; hence they cause infarction and necrosis, which is the pathological hallmark of mucormycosis [5]. A CT scan, which is the most commonly used imaging modality, is used to identify invasion but MRI is considered superior to CT in delineating the intracranial extent. The accepted mode of treatment is a combination of antifungal therapy, aggressive surgical debridement and reversal of the underlying immunocompromising condition whenever possible. Amphotericin B is the drug of choice, especially for mucormycosis [6].Here we present a case of invasive mucormycosis in a 40yr old male diabetic patient who presented with pain, puffiness, loss of vision in one eye along with ophthalmoplegia, without any nasal symptoms with a clinical picture which resembled cavernous sinus thrombosis.

2. Case Report

- A 40yr old male patient presented to the outpatient department with complaints of pain, puffiness, loss of vision in the right eye with inability to open the eye since 2 days. He denied any history of associated fever, nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, bleeding from the nose, headache or vomiting. The patient also had a medical history of insulin dependent diabetes mellitus for three years on irregular treatment. He did not give history of smoking, alcohol or use of any drugs.On examination the patient was afebrile with a pulse rate of 96 per minute, blood pressure of 134/80mm Hg and respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min. Systemic examination of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems revealed nothing significant. An examination of his nose and paranasal sinuses showed a deviation of the nasal septum to the left, hypertrophied middle turbinate and mucoid discharge in the right middle meatus and tenderness of right frontal and maxillary sinuses. A nasal endoscopy was done which added no other information to the clinical examination findings. Ophthalmological examination revealed periorbital edema, ptosis with chemosis, fixed pupil not responding to light (direct and consensual light reflexes were absent), no perception of light on vision testing and restricted extraocular movements that revealed affection of III, IV & VI cranial nerves [fig.1].

| Figure 1. Patient photograph showing periorbital edema and proptosis of right eye |

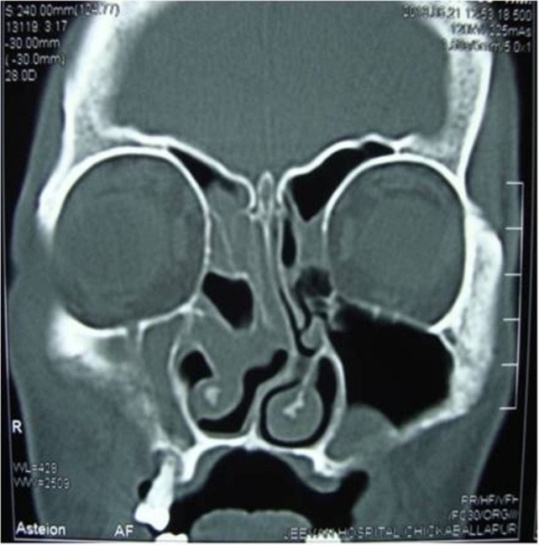

| Figure 2. CT scan showing polypoidal mucosal thickening of right maxillary and ethmoidal sinuses and a polyp in left maxillary sinus |

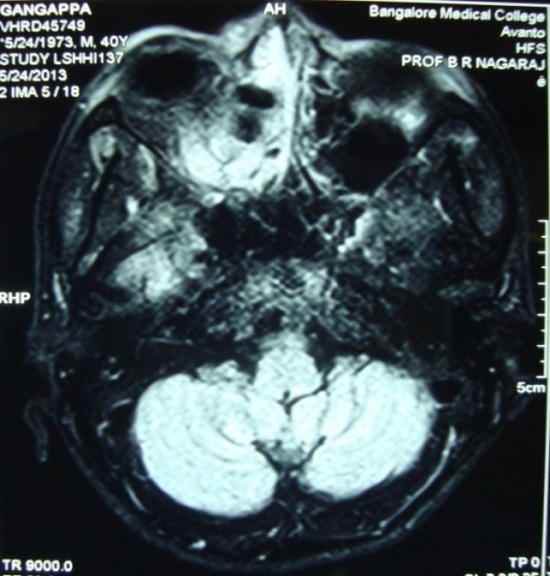

| Figure 3. MRI showing polypoidal soft tissue mass in the right maxillary, ethmoidal sinuses and in left maxillary sinus |

| Figure 4. MRI showing normal cavernous sinuses |

| Figure 5. Photomicrograph showing the broad aseptate hyphae of the fungus |

3. Discussion

- Invasive fungal sinusitis, previously thought to be a rare clinical entity is now being encountered more frequently. Being a disease which is hard to diagnose and treat, it has high mortality rates. In one study the overall survival rate was 49.7%, poor prognosis being associated with renal/liver failure, altered mental status, and intracranial extension [1]. A recent review showed that mortality was higher for mucormycosis infected patients (29%) as compared to patients with aspergillus infections (11%) irrespective of the underlying conditions. They also showed that diabetics had higher morbidity and mortality and concluded that high index of suspicion, early diagnosis and treatment could help reduce mortality rate [7].Acute invasive fungal sinusitis is an aggressive disease with a high mortality rate. Fungal invasion often occurs within the nasal cavity, most commonly at the middle turbinate. It manifests by sequentially involving the nasal cavity, sinuses, orbit and eventually the brain [8]. This makes our patient an atypical subject as he first manifested with ophthalmological symptoms with no symptoms indicative of nose or paranasal sinus involvement by the fungi such as fever or rhinorrhoea which are some of the most common presenting symptoms. Loss of vision as an initial symptom is an atypical manifestation of this condition. Chopra et al have reported this feature in 22% of the patients reviewed in their study [9]. The early ocular involvement with periorbital edema, chemosis, loss of vision and restriction of movements of extraocular muscles commonly occurs in cavernous sinus thrombosis [10] as was seen in this patient.Nasal mucosal findings are considered to be the most consistent findings and endoscopic examination is recommended in all high risk patients [4]. Our patient showed nasal endoscopic changes 8 days after manifestation of initial symptoms. Features suggestive of the aggressive nature of the disease such as mucoperiosteal thickening / opacification, bone erosion or orbital extension [11] were not present on the CT scans. No features suggestive of intraorbital or intracranial extension were found on the MRI either. These findings are suggestive of vascular route of dissemination.The poorly controlled diabetes of the patient could be a significant contributing factor in the rapid and fulminant progression of the disease with the atypical manifestations. Poorly controlled diabetes with acidosis impairs cellular immunity. This predisposes patients to develop mucormycosis as their neutrophils have reduced ability to phagocytose and adhere to the endothelial lining. The acidosis and hyperglycemia provide an ideal environment for fungal growth [12].The implications of this case are important because ophthalmological features in the absence of nasal symptoms or fever must be considered as an early manifestation of invasive fungal sinusitis. This is especially important in patients who are immunocompromised such as uncontrolled diabetes who also have other risk factors frequently such as old age, alcoholism, hepatic failure, drug abuse, post surgical or post traumatic events. As delay in diagnosis is one of the causes for high mortality, a high index of suspicion is needed and appropriate use of imaging and histopathological examination with prompt treatment can be life saving in these patients. Empirical treatment with liposomal amphotericin B has been given in patients with neutropenia and fever. It has shown similar efficacy when compared to conventional amphotericin B but lesser breakthrough infections and nephrotoxicity have been reported with it [13]. The role of empirical therapy in other risk groups is not clear. The effectiveness of antifungals in prophylaxis against invasive fungal sinusitis is not clearly elucidated. Although liposomal amphotericin B and posaconazole have been used [14], safety and efficacy data preclude routine prophylaxis. The role of intranasal amphotericin B spray remains unclear.

4. Conclusions

- Invasive fungal sinusitis must be suspected in all high risk patients despite absence of sinonasal symptoms and radiological features of the same. Serial endoscopic examinations with biopsy should be done when necessary and surgical debridement with empirical antifungal therapy should be part of the management protocol in such situations. Prophylactic strategies for high risk subpopulations needs to be further evaluated.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML