Fadamiro Joseph Akinlabi, Adedeji Joseph Adeniran

Department of Architecture, The Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Adedeji Joseph Adeniran, Department of Architecture, The Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

The built environment is an historical document in the physical realm. They reflect the history of man in the past and their memories in the present should be studied to give direction to the future in this age of modernization and destruction of the “spirit of the city”. In Ile-Ife, Nigeria, an ancient Yoruba city termed “the source”, three such landscapes and their elements are uncommon examples. These are Oranmiyan Staff and site which is ancestral, Oke Mogun which is cultural and religious, and Oke Yidi battle ground which is socio-spatial. These three places were investigated with the aim of identifying their characteristic “memory spirit” towards their promotion as valuable ecotourism centres. To achieve this, 140 heterogeneous purposeful samples of Ile-Ife dwellers that have attained the age of accountability were randomly selected. Questionnaire containing variables on memories were administered on them. Results of the descriptive and inferential statistics of the nominal and ordinal data sets obtained had shown that the landscapes are soaked with different memories both positive and negative. The study has established significant correlation between place and memory with Chi-Square analysis as required by scientific enquiries. The study concluded with recommendations that the pains and pleasures memorably associated with these three landscapes could be turned into gains through ecotourism promotion strategies.

Keywords:

Place, Memory, Cultural Landscapes, Tourism, Heritage

Cite this paper: Fadamiro Joseph Akinlabi, Adedeji Joseph Adeniran, Place and Memory: An Evaluation of Ecotourism Potentials of Selected Cultural Landscapes in Ile-Ife, Nigeria, American Journal of Tourism Management, Vol. 3 No. 1A, 2014, pp. 20-32. doi: 10.5923/s.tourism.201401.04.

1. Introduction

A place is a space with identity[1]. The identity of a place is not just in name but in its character which could be physical or emotional. The emotional character a place exhibits, gives it the true identity which is symbolic and relates to human’s experience. Our memories and emotional experience of place may bring feelings of fear and death, love and life, struggle and violence. Thus, a place may be fascinating or frustrating, beautiful or horrifying, memorable or forgettable, liked or disliked[2]. Lynch[3] argued that an image of a place is “soaked with memories and meanings”. Consequently, the emotional meanings attached to or evoked by the elements of the urban environment is as important as or more important than the physical aspects of people’s imagery[4 cited in 1]. This concept of environmental attachment is also called “spirit of place”, “genius loci” or “topophilia” broadly defined “to include all of the human beings effective ties with the material environment”[5]. Langenbach[5] insisted that feelings that one has towards a place is more permanent and longer lasting when it is mixed with the memories of human incidents because of being the locus of memories. Indeed, as Rossi[6] pointed out, the union between man’s past and future “exists in the idea of the place that it flows through in the same way that memory flows through the life of a person”.The aim of this study is to evaluate the importance of the symbolic emotional memory of three selected cultural urban landscapes in Ile-Ife, Nigeria with a view to re-vitalizing their historic significance and ecotourism values. The three places which are representatives of their groups are: Oranmiyan Staff and site, Mopa, which is ancestral; Oke Mogun is a traditional and religious site while Oke Yidi, is a socio-spatial and political landscape.

2. Literature Review

Places where certain historic events occurred have been of great important in the African culture and are fast becoming urban cultural landscapes because of physical urban developments that have reached such places. They are often marked with monuments or designated as “taboo” places being seen as sacred. Such landscapes include place of conflict between communities, kingdoms or empires, sacred religious grounds and tomb stones of ancestral city founder. These landscapes are the physical presence of the past linked with the present and constantly relay the experiences of past generations and testify to the hopes and aspirations for the future. This assertion is true because life is annexation of space[7] and there is a tie between person and place. For instance, Aboriginal Australian people view the land around them everywhere filled with marks of individual and ancestral origins and dense with story and myth. Also, across the Tasman, in New Zealand, Maori beliefs emphasize connection to place and to the land as constitutive of identity[8].In pre-modern cultures from Australia to America and within contemporary cultures there is a basic notion of a tie between place and human identity[9,8]. It was argued that persons and places intermingle with one another in such a way that places take on the individuality of persons, while persons are themselves individualized and characterized by their relation to space. Malpas[8] also gave the example of Bachelard where “the life of the mind is given form in the places and spaces in which human beings dwell and those places themselves shape and influence human memories, feelings and thoughts” to emphasize this concept arguing that “the stuff of or inner lives is thus to be found in the exterior spaces or places in which we dwell, while those same spaces and places are themselves incorporated within us”.Places and cultural landscapes are interrelated because landscapes are places, and are defined as “sets of relational spaces each enjoying emotions, memories and associations derived from personal and interpersonal shared experience”[10]. For instance, in Berlin the historical “Gestapo Terrain” is now known as the site of the exhibit Topography of Terror and is a high-profile site confronting visitors with elements of history in order to make them think and contemplate. Also, Berlin’s memorial for the murdered Jews of Europe has emerged as “memory district”[11]. Till[11] investigated the intended meanings and functions of these sites of memory and discovered that, like elsewhere, trauma sites have turned out to be tourist magnets of “dark tourism”.In America, national trauma in collective memory is associated with December 7, 1941 when the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbour and September 11, 2001 when the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon collapsed after a terrorist attack. Indeed, as Kaelber[12] rightly put it, “trauma is not spatially amorphous but inscribed in place. Its analysis must address the physicality of a location and quite literally embodies a traumatic event and how people relate trauma to a physical space, interact with it, and commemorate it” and in this way structures of places are transposed into structures of memory.Furthermore, Tumarkin[13 cited in 12] named six epicenters of national trauma and tragedy as follows:Port Arthur Tasmania, the location of a former hellish penal colony and in 1996 of a massacre that claimed over seventy casualties; Shanksville, Pennsylvania a site related to the terrorist attacks in September 11; the Kuta region on Bali as a place of the deadliest terrorist attack in Indonesia’s history, in which more than 200 people were killed and another 200 people wounded in 2002; Moscow, targeted in several recent terrorist attacks and sieges; Sarajevo, the object of a Serbian siege and urbicide from 1992 to 1995; and Berlin, the headquarters of Nazi terror in world war II.According to Tumarkin[13], these traumascapes are “much more than physical settings of tragedies, they emerge as spaces where events are experienced and re-experienced across time” and such sites has capacity to trigger a mixture of elementary affective states-fear, sorrow, pain-including empathy.Till[11] argued that “people mark social spaces as haunted sites where they can return, make contact with their loss, contain unwanted presence, or confront past injustices” concluding that these places and sites “narrate national pasts and futures through the spaces and times of a city that is itself place of social memory”. Commenting on Till’s[11] illustration of this assertion with Berlin, Kaelber[12] exclaimed that the trauma infused into Berlin’s cityscape by its violent past could not be ignored and will continue to shape the past’s commemoration. It is in this process that a geographical location transforms into memorial site that is invested with meaning and invokes rituals of commemoration according to Jordan[14].In addition to the foregoing, Rapoport[15] asserts that ritual, especially as a religious practice, is important in urban contexts. For instance ritual played a central role in the operation of dispersed Mayan settlements which were unified through ritual[16]. In view of this and also to reinforce and maintain the cultural evolution and identity of cities, ritual landscapes are retained in urban settlements and designated as sacred. These sacred and ritual places may be for the worship of national deities or ancestral worship[17] (Obateru, 2003) and are the cultural religious elements of the city. The shrines are essentially cultural landscape elements in their domain and are for generational memories.

3. Ile-Ife: An Overview

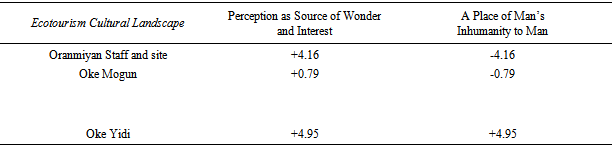

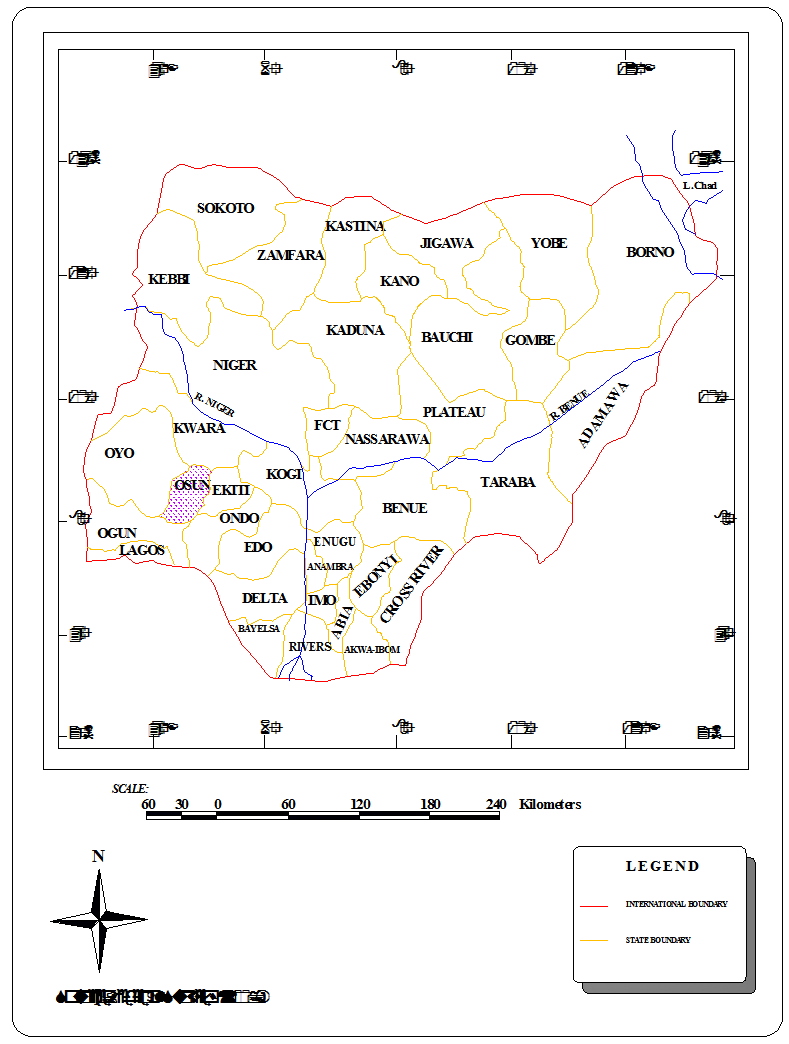

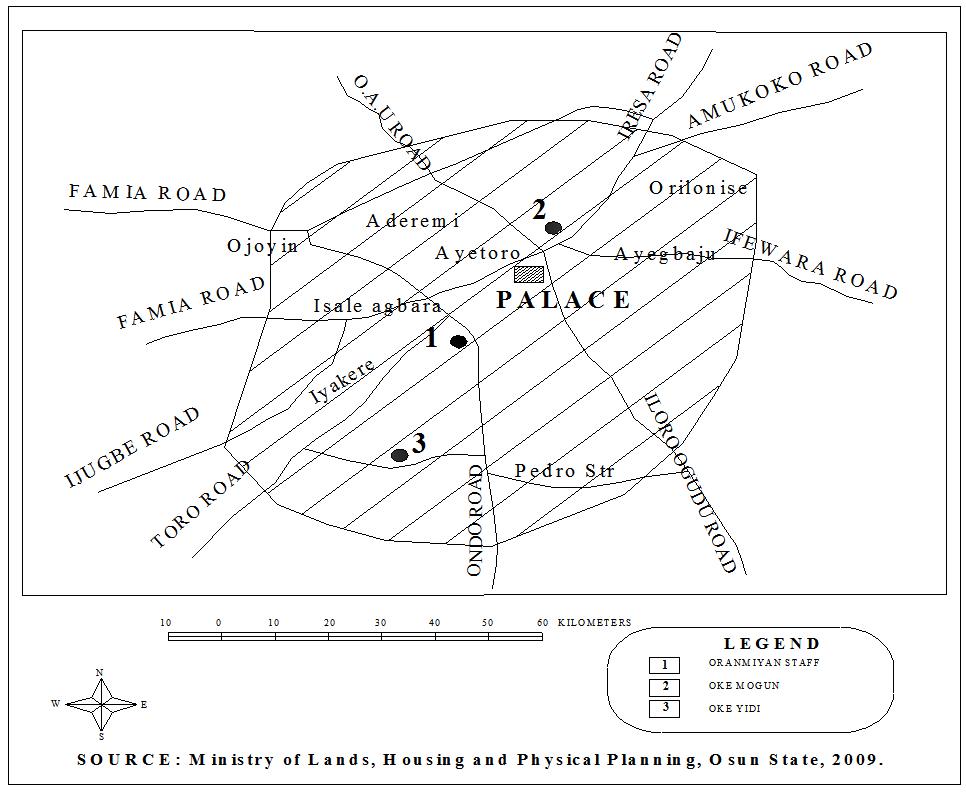

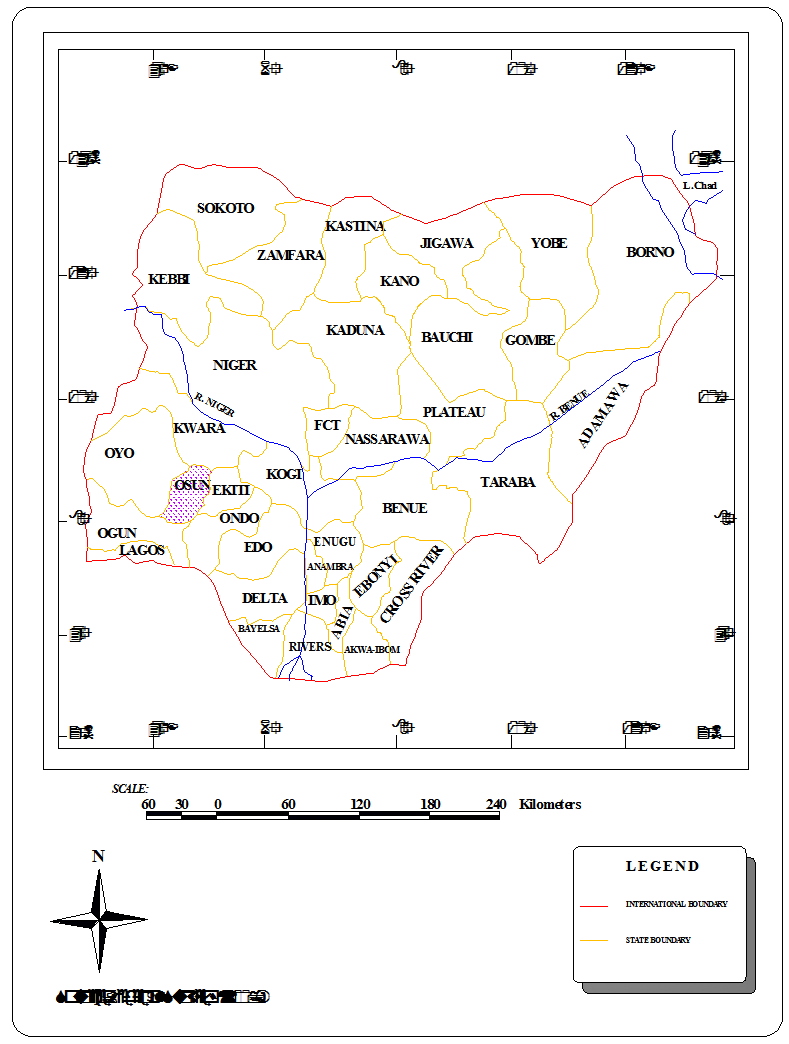

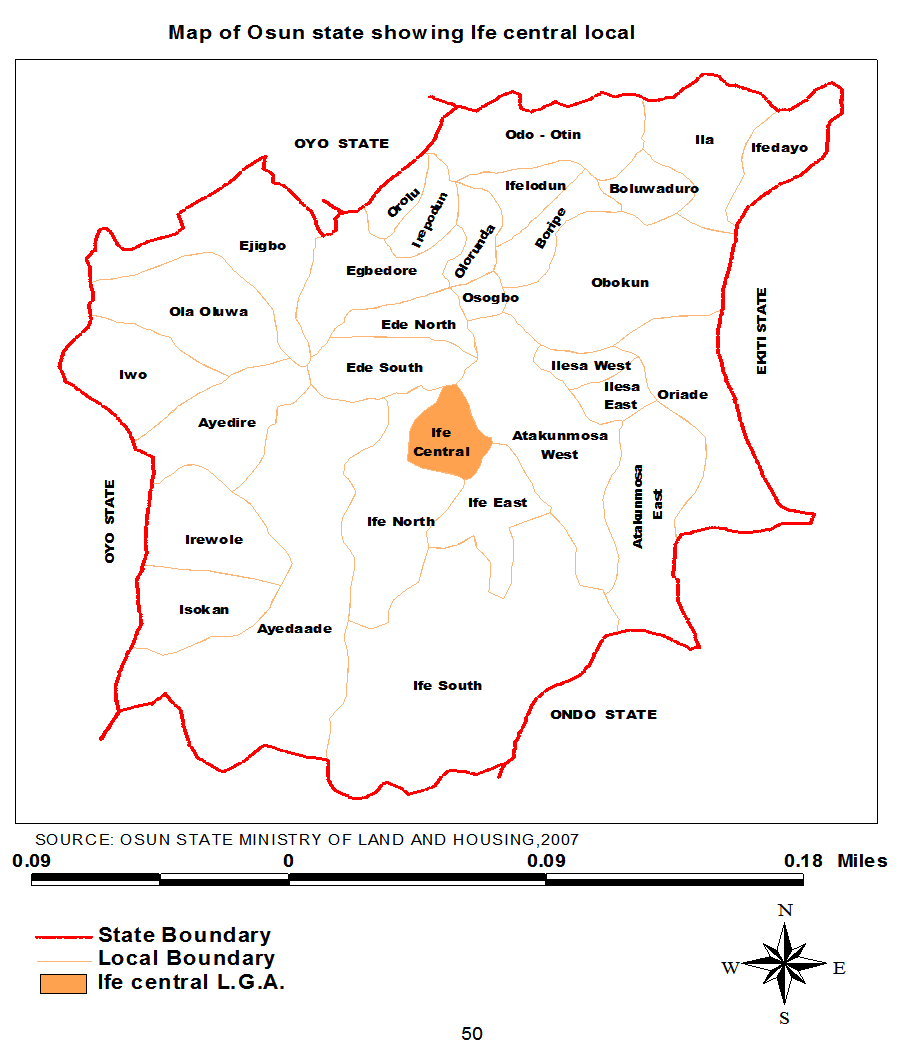

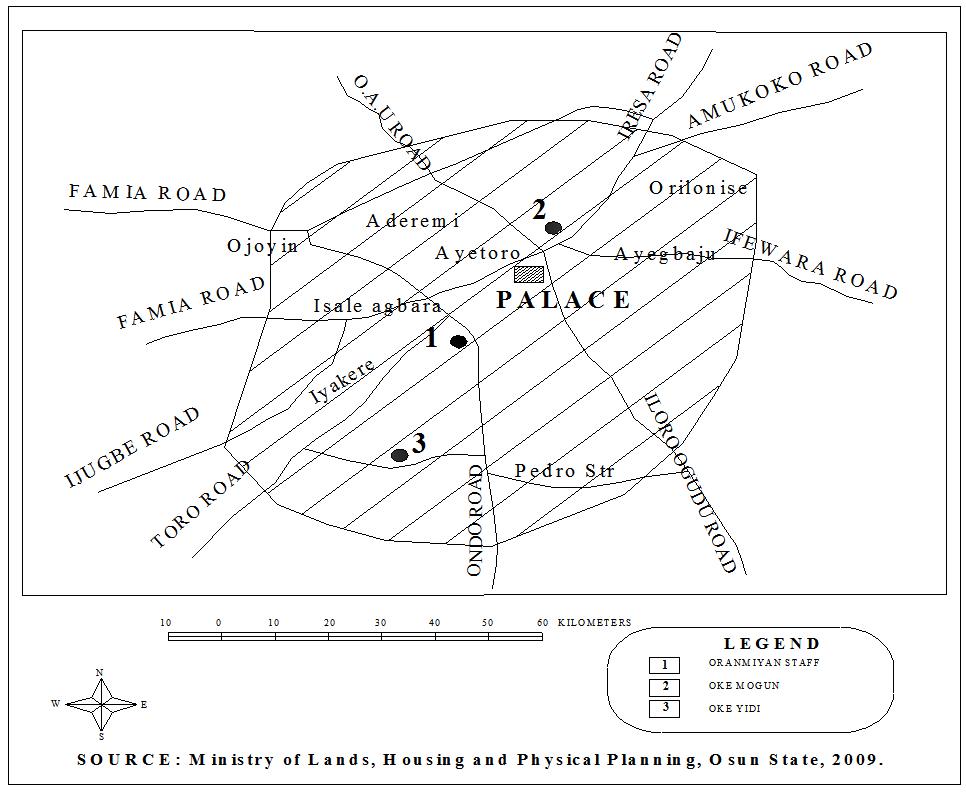

Ile-Ife is a southwest ancient city in Nigeria (Figure 1). It is a major city not only in Osun State (Figure 2) and Nigeria but also in the West African sub-region and the world at large. The city occupies a central position as the mythical home of the Yoruba race. Ile-Ife (Figure 3) founded by Oduduwa who in some version of the myth created the world at Ile-Ife while in others he arrived from outside[18] (Eades, 1980). The Yorubas consider Ile-Ife as the cradle of creation and civilization. “Legend says that it was at Ile-Ife that Oduduwa, sent by Olodumare, the Yoruba creator (god), established the first land upon the waters that covered the earth, thus founding Ife”. His sons spread to other parts of Yoruba to create further kingdoms[19, 20]. Obateru[19] asserts the primacy of Ile-Ife among Yoruba cities as the spiritual and theocratic capital city of Yoruba. Indeed, Yoruba tradition regards Ile-Ife not only as the centre of Yorubaland but also of the world where God created the earth and man[21,22].To corroborate his support of this historic-cultural origin of Ile-Ife, Obateru[17] asserts that this view may have been sustained by the possibility of Ile-Ife being the burial place of the great ancestor of the Yoruba aborigines. His conclusion was deduced from Mumford[23] who noted that:“Mid the uneasy wanderings of Paleolithic man, the dead were the first to have a permanent dwelling: a cavern, a mound marked by a cairn, a collected barrow. These were landmarks to which the living probably returned at intervals, to commune with or placate the ancestral spirits”.  | Figure 1. Map of Nigeria Showing Osun State |

| Figure 2. Map of Osun State Showing Ife Central and Ife East Local Government where the Three Ecotourism Cultural Landscapes are Located |

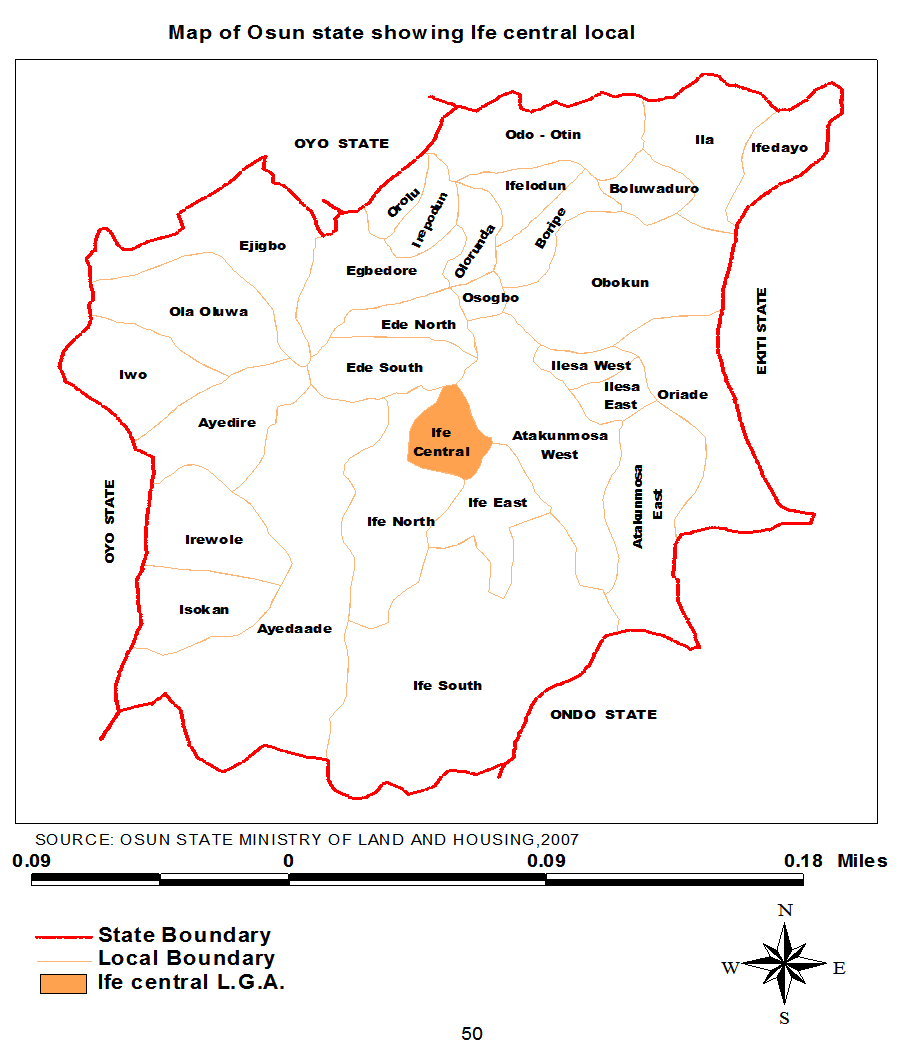

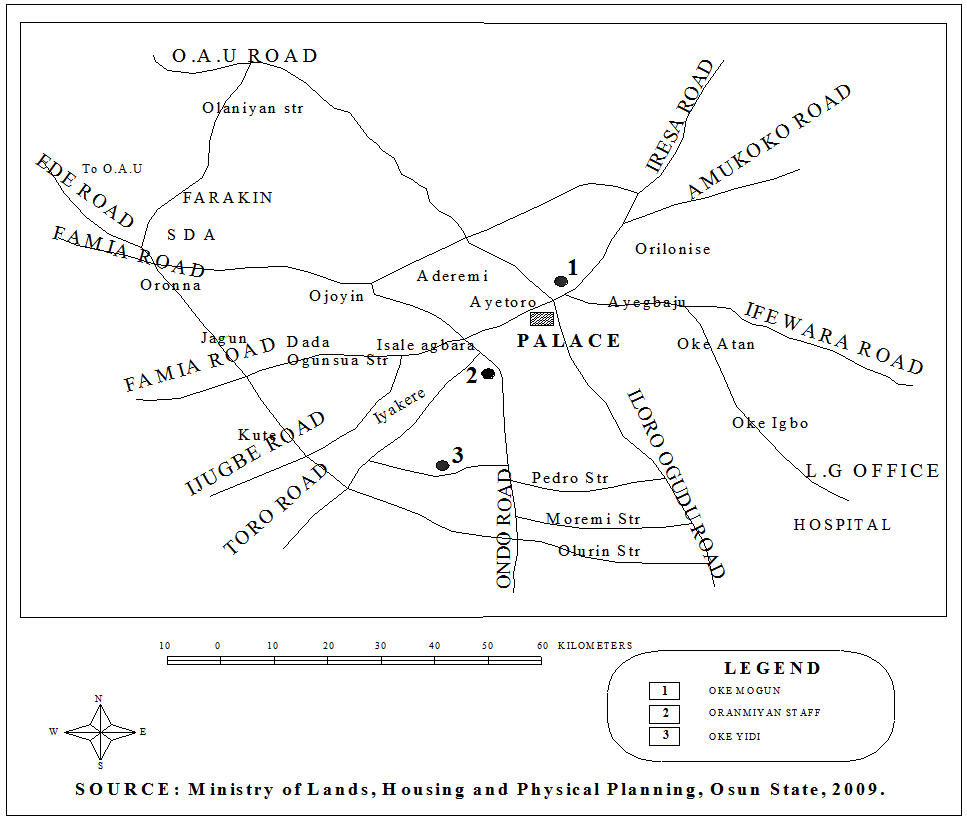

| Figure 3. Ile-Ife Township Map |

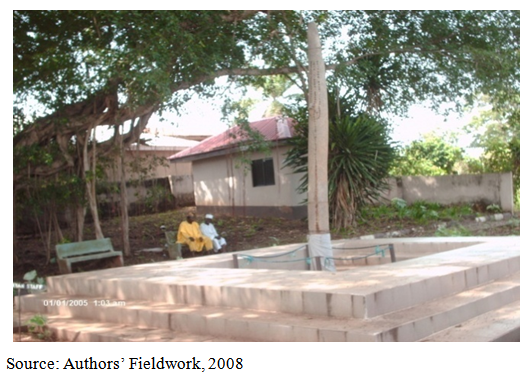

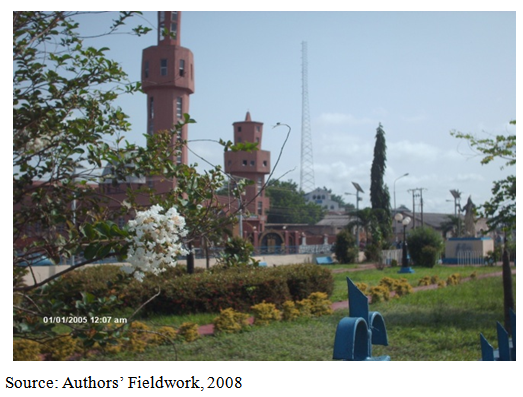

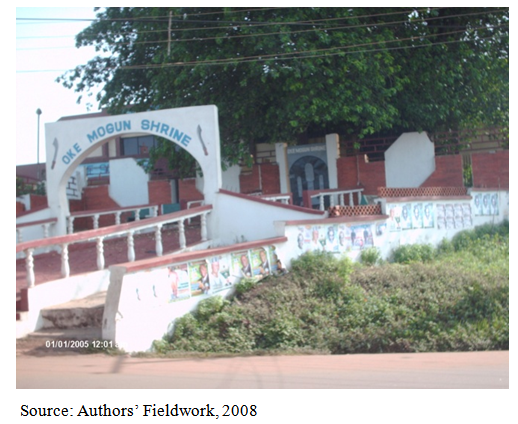

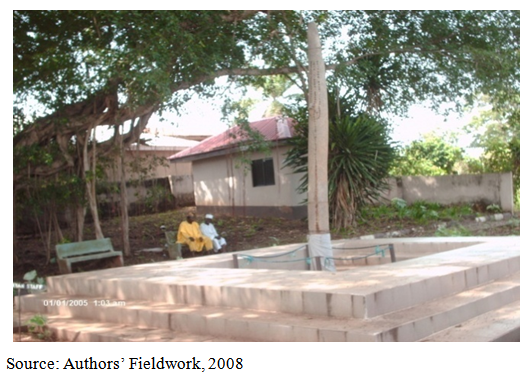

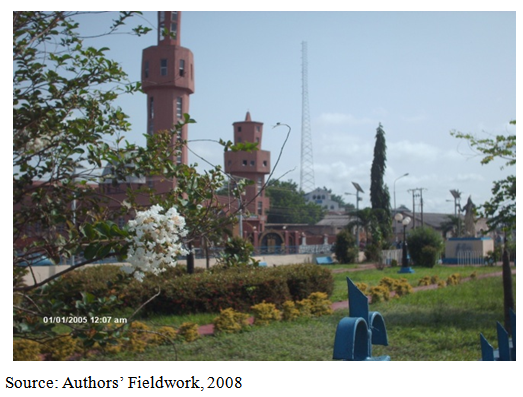

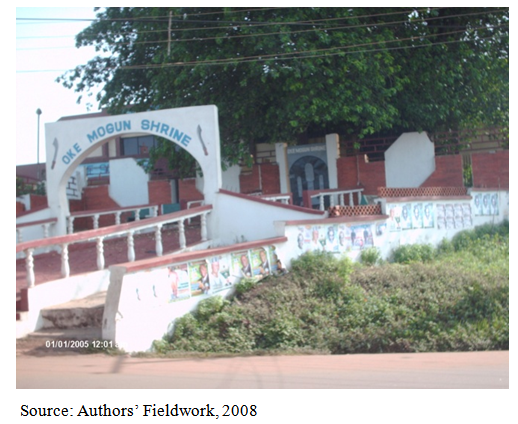

Thus, according to Obateru[17] Ile-Ife has commanded the reference of all Yorubas who have regarded it as their ancestral home and spiritual capital city since those primeval days, and even up to now. Oranmiyan Staff and site (Plates 1 and 2) with an area of 0.43 Hectare at Oranmiyan Street, Ile-Ife is one of such landmarks which is the tomb stone of Oranmuiyan the youngest of Oduduwa’s sons and the founder and first Alafin of old Oyo.Oduduwa was the founder of Ile-Ife whose shrine (Plate 3) is in the front of the Ile-Ife palace. Johnson[24 cited in 17] provided a complete description and interpretation of the staff (tomb stone ) as follow :“This obelisk is about 20 (twenty) feet in height, and about 4 feet square in width at its base; it tapers to a point, and has upon one face of it, several spike nails driven into it, and some carvings as of ancient characters. The nails are arranged in such an ordered manner as to render them significant. First, there are 61 in a straight line from the bottom upwards at intervals of 4 inches on either side of this and from the same level on top, two parallel lines of 31 nails each running downwards and curving below to meet those of the middle. Then in the space between these three rows of parallel lines, and about the level where they converge, is found the most conspicuous of the carvings.What is conjectured as most probable in these arrangements is that the 61 nails in midline represent the number of years Oranyan lived, and that the 31 each on either side indicates that he was 31 when he began to reign, and that he reigned for 31 years, the year he began to reign being counted twice as is the manner of the Yorubas, and that the carvings are the ancient characters Resh and Yod which stand for Oranyan”.It is an impressive granite monolith erected on the supposed grave of Oranyan (now pronounced as Oranmiyan). Oke Mogun is the location of the shrine of Ogun, the god/divinity of iron, hunting and war, a national Yoruba deity where the annual highest ceremonial, cultural and traditional religious worship in Ile-Ife called ‘Olojo” is celebrated. The shrine (Plate 4) is located at Enuwa Street, Ile-Ife in the palace neighbourhood.The shrine is also significant and symbolic in the procedure for the coronation of “Oni”, the royal ruler of Ile-Ife and traditional head of the Yoruba Kingdom. | Plate 1. showing Oranmiyan Staff and site, entrance to the second yard of the landscape and ancient trees, Ile-Ife, Nigeria |

| Plate 2. showing Oranmiyan Staff, its base and a renovated old structure on the site including garden furnitures, Ile-Ife, Nigeria |

| Plate 3. showing Oduduwa Statue located inside the Oduduwa Park in front of the Royal Palace of Oni of Ife, Ile-Ife, Nigeria |

| Plate 4. showing the renovated modern entrance, fence and shrine under a big forest tree of Oke Mogun, Ile-Ife, Nigeria |

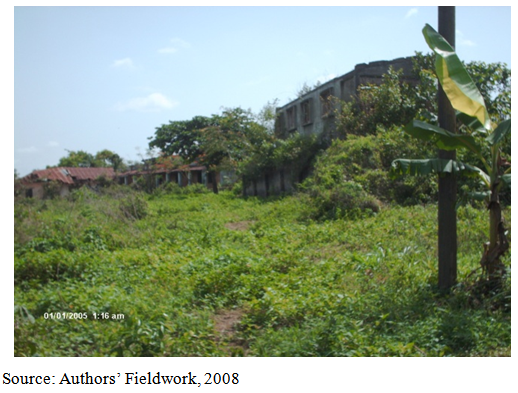

| Plate 5. Showing one of the dilapidated buidings at Oke Yidi war ground, Ile-Ife, Nigeria |

| Plate 6. Showing more dilapidated buildings at Oke Yidi war ground, Ile-Ife, Nigeria |

| Figure 4. Locations of the Three Cultural Landscapes in the Urban Core Areas of Ile-Ife, Nigeria |

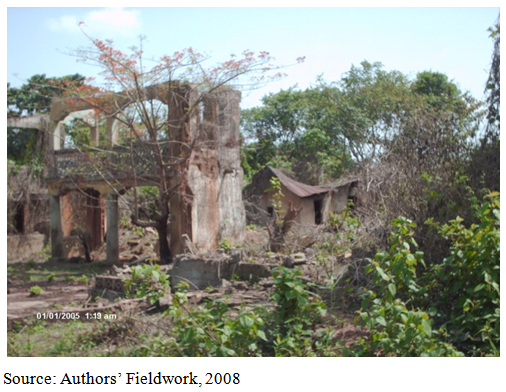

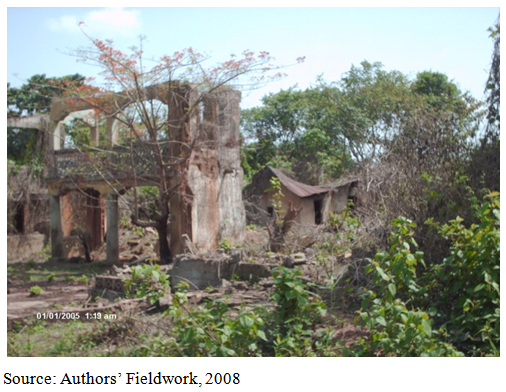

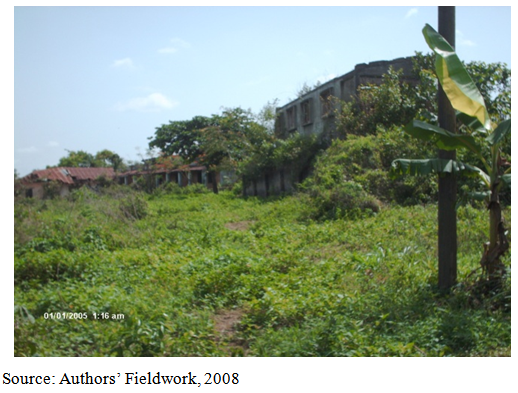

Oke Yidi is a neighbourhood in Ile-Ife. The striking character of this landscape is that it represents the physical memory of the last communal war between Ile-Ife and Modakeke with common boundary which occurred between 1996 and 1998 where thousands of lives were lost. The historic war had come in sequence since the 20th century. Oke Yidi (Plates 5 and 6) was the major battle ground in the war being a major common boundary between Ile-Ife and Modakeke. According to Obateru[17],“Modakeke (meaning “I keep quiet”) was founded by Oyo refugees probably in the early 1830s at the outskirt of Ile-Ife. As a result of Fulani invasion of northwestern Yorubaland, including Ife territory, a large number of Oyos and Ifes flocked into Ile-Ife for protection. Soon afterwards, trouble erupted between the Ifes and the Oyos and the latter were ordered to leave the city to resettle at its fringe”.By 1884 the population of this fringe settlement named Modakeke had risen to between 50,000 and 60,000 because of its rapid growth[24]. Traditionally, Ile-Ife has eight high chiefs controlling the eight quarters of the city, including Iraiye which is the core of Modakeke and controlled by Obalaye[17].

4. Research Methodology

Three historic memorable cultural landscapes (Figure 4) that are representatives of their groups were selected. These are Oranmiyan Staff and site, Ogun shrine at Oke-Mogun and Oke-Yidi, a riot site/location during the 1996-1998 Ife-Modakeke communal crises. The study population consists of all Ife dwellers while the sampling frame consists of heterogeneous respondents, those dwellers who have reached the age of accountability (at least 9 years) at the time of the riot and are indigenes of Osun State living in Ile-Ife/Modakeke.A total of 140 respondents were randomly selected to give their memory perception of the three selected historic cultural landscape through questionnaire administration. The questionnaire consisted of memory perceptions of the respondents on the selected places structured as follow:1.Most visually accessible place.2.Most memorable place. 3.Place with highest source of wonder and interest.4.Most perceived as a place of honor and fear.5.Most demoralizing place.6.Most lonely and impoverished place.7.A place of man’s inhumanity to man. 8.Most perceived as a place of violence and struggle.

5. Discussion of Findings

5.1. Ecotourism Cultural Landscapes with Positive Significance

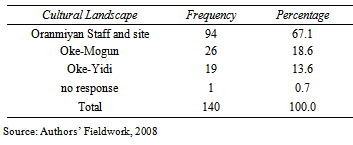

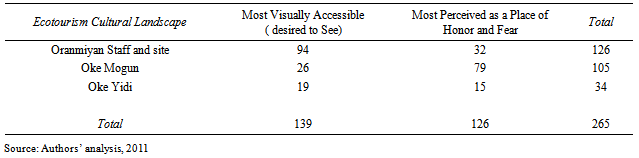

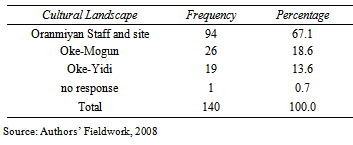

Table 1 shows the pattern of visual accessibility of the three selected cultural urban landscapes as reported by the respondents.Table 1. Visual Accessibility of the Selected Tourist Sites in Ile-Ife, Nigeria

|

| |

|

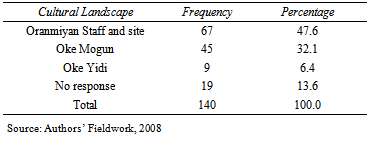

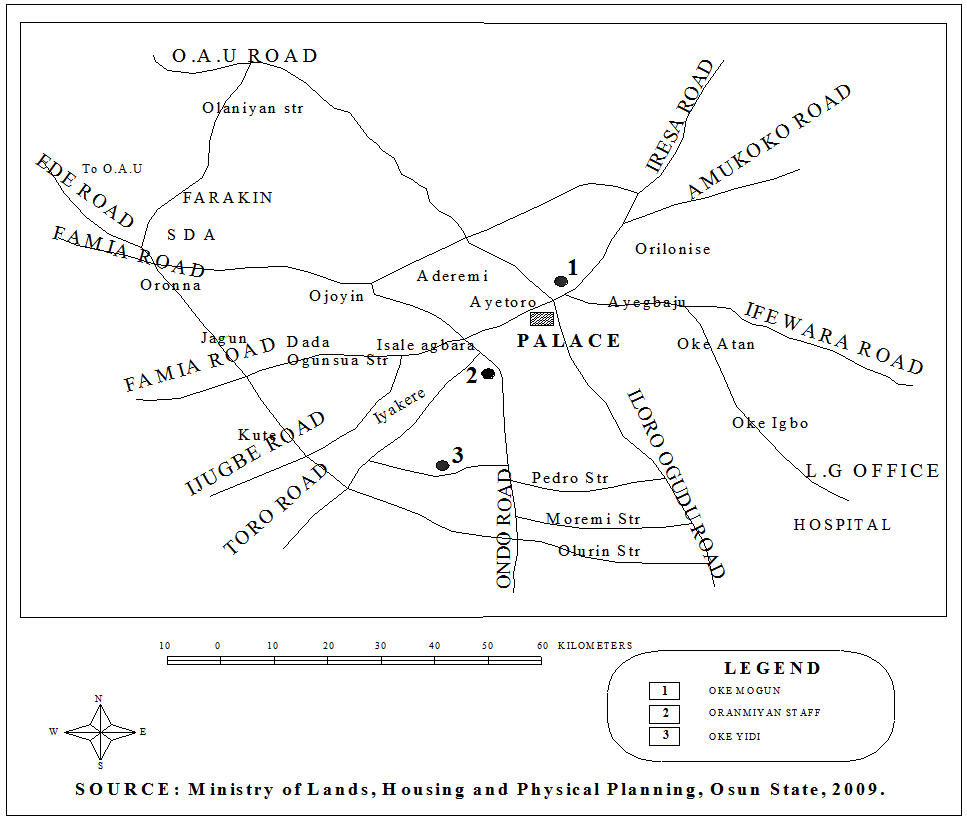

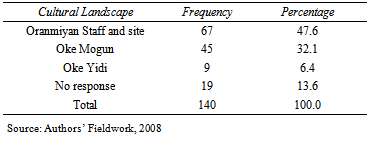

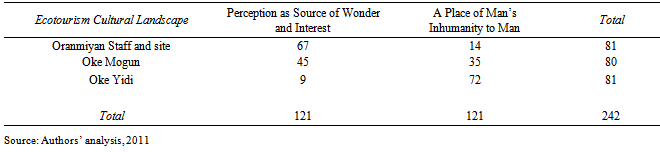

From table 1, the place with the highest visual accessibility is Oranmiyan Staff and site with 94 (67.1%), followed by Oke-Mogun, 26(18.6%) and Oke-Yidi, 19(13.06%) while a respondent (0.7%) gave no answer to this question. Obviously, the location of these ecotourism cultural landscapes (Figures 3 and 4) is not the only major cause of the wide variation in this variable because the three are in the heart of the city with equal spatial advantage but there may be emotional implication for the pattern. Oranmiyan Staff and site does not have any element that create fear and horror and so people willingly pass around it along their daily route being already in the heart of the city. This is not the case with Oke-Mogun, though also in the heart of the city. Oke-Mogun has some element of fear because it is a place of annual sacrifice and ritual during Olojo Festival which is the annual ritual of the whole ancient city and Yorubas in diasporas. On the other hand, the deserted nature of Oke-Yidi with many dilapidating unoccupied buildings coupled with the negative memory of horror of warlike riot will normally make many people divert their circulation route away from the place. Indeed, places can be attractive like an environmental magnet being centripetal while others may be repelling being centrifugal, depending on the spirit of each place. Table 2 shows the responses on the perception of wonder and interest of the selected three urban ecotourism landscapes in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. The frequency for Oranmiyan Staff and site is 67(47.6%), followed by Oke Mogun, 45(32.1%) and Oke Yidi war ground, 9(6.4%).Table 2. Perception as Source of Wonder and Interest of the Selected Tourist Sites in Ile-Ife, Nigeria

|

| |

|

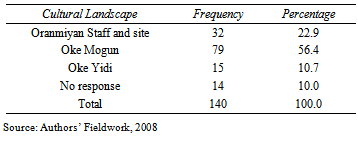

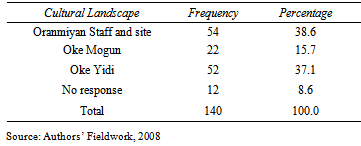

The implication of this pattern is that people do not create an interest in nor wonder about places of negative memories but about places of positive memories. In addition to this, the characteristics of Oranmiyan Staff as earlier described cannot but attract wonder in people’s memory of it. This is much similar to Oke Mogun considering the large crowds that worships there on annual basis during Olojo Festival. Oke Mogun is a place with a simple shrine under a tropical forest tree. People will normally wonder about such a place with traditional worship elements. In the case of Oke Yidi, the low interest may be attributable to the memories of negative event it attracts.Table 3 shows the response on the perception of honor and fear of the selected tourist sites in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Oranmiyan Staff and site has the frequency of 32 (22.9%), Oke Mogun, 79(56.4%), followed by Oke Yidi war ground 15 (10.7%). The highest value for Oke Mogun shows the level of reference the Yoruba people has for sacred religious grounds. Such reference is lesser for Oranmiyan Staff and site which does not attract general annual religious worship but is a monument for ancestral origin of the Yorubas but not equally worshipped. The low value for Oke Yidi shows that Yorubas have no honour nor regard for violence. Table 3. Perception of Honor and Fear of the Selected Tourist Sites in Ile-Ife, Nigeria

|

| |

|

5.2. Ecotourism Cultural Landscapes with Negative Significance

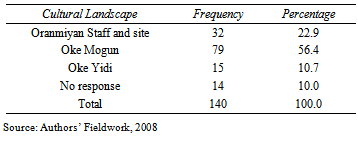

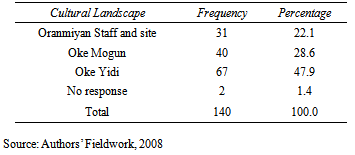

Table 4 shows the pattern and its magnitude of the landscapes that are most unforgettable. From the table, in descending order, Oke Yidi warlike riot ground has a frequency of 67(47.9%), Oke Mogun, 40(28.6%) and Oranmiyan Staff and site, 31 (22.1%). This implies that landscapes that have negative memories are not easily forgotten compared with landscapes of positive memory. While the pains of unpleasant experiences are inscribed indelibly in the memory, the joy of pleasurable events easily fades away. The memory of each experience that is retained in the places through which they flow differs. Pleasantness may fade completely to zero point while the “cells” of agony may never die.Table 4. Perception of the Highest Memorable of the Selected Tourist Sites in Ile-Ife, Nigeria

|

| |

|

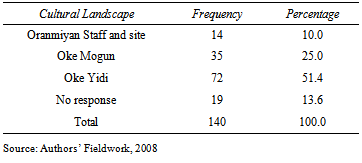

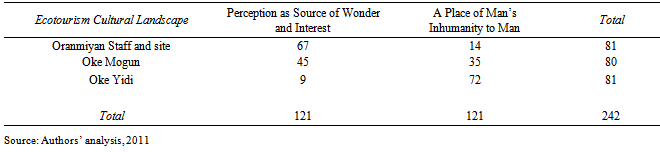

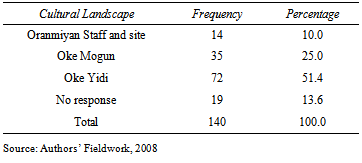

This picture is more clear in Table 5 which shows memory perception on the landscape of man’s inhumanity to man. From Table 5, Oke Yidi warlike riot ground has a frequency of 72 (51.4%), followed by Oke Mogun, 35 (25.0%) and Oranmiyan Staff and site, 14 (10.0%). Oke Yidi is the place where the blood of great warriors of the land was shed. Strong hands were hanged down and the torrents of bullets keeps re-echoing in the air years after the warlike riot.Table 5. Perception of the Place of Man’s Inhumanity to Man of the Selected Tourist Sites in Ile-Ife, Nigeria

|

| |

|

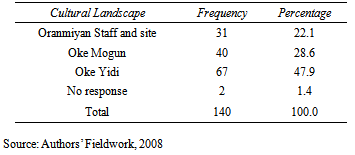

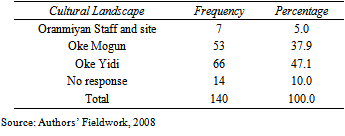

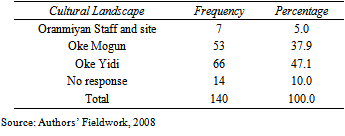

How can the memory of panic, horror, anguish, indignation and blood baths that have soaked the ground but still keeps flowing like run-off water in the minds of the people be wiped away by the “water” of time. Oke Yidi is the epitome of animalistic inhumane treatment of other human creatures. It will continue to be the black book of dark hours in the history of the city, a physical representation of history that should never be repeated! Presently, it is deserted with dilapidating buildings (Plates 4 and 5). On the other hand the response on Oke Mogun may not be unconnected with the nature of the ancestral worship that are carried out there especially during the coronation of new Ooni, the paramount king while that of Oranmiyan Staff and site, though scanty, may be attributed to the overwhelming conquering war-life of Oranmiyan during his lifetime.Table 6 shows the response on the most demoralizing landscape. Oke Yidi with frequency of 66 (47.1%) has the highest, followed by Oke Mogun, 53 (37.9%) and Oranmiyan Staff and site, 7(5.0%).Table 6. Perception of the Most Demoralizing of the Selected Tourist Sites in Ile-Ife, Nigeria

|

| |

|

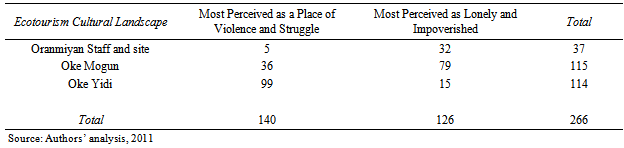

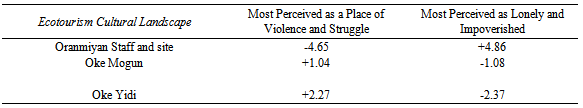

Definitely Oke Yidi and Oke Mogun present themselves as places with demoralizing elements in their history and current status. Oke Yidi is associated with pain and absence of peace. In the case of Oke Mogun, religious bias may have played a major role. Table 7. Perception as Place of Violence and Struggle of the Selected Tourist Sites in Ile-Ife, Nigeria

|

| |

|

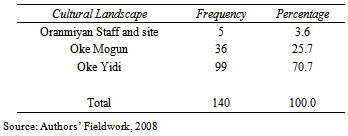

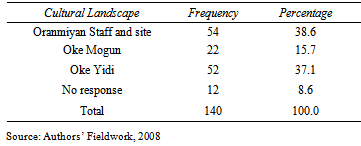

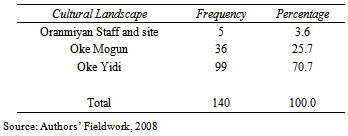

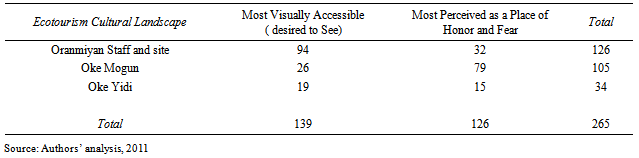

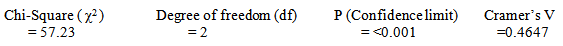

Table 7 shows the response on the ecotourism cultural landscape that is most perceived as a place of violence and struggle. Oranmiyan Staff and site, 5(3.6%) has the lowest followed by Oke Mogun, 36 (27.7%) and Oke Yidi, 99(70.7%) in ascending order. The value for Oke Yidi is an eloquent testimony of lingering memory of violence and age-less struggle for existence between the dwellers of the main city, Ile-Ife and the southern Modakeke. Little wonder that impoverishment and loneliness characterize the memory of such place as shown in table 8. From table 8, Oke Yidi with a frequency of 52(37.1%) is only inhabited at the borders, Oranmiyan Staff and site, 54(38.6%) is a parcel of landscape without any dwelling but a shrine while Oke Mogun with frequency of 22 (15.7%) is a shrine.Table 8. Perception of the Lonely and Impoverished of the Selected Tourist Sites in Ile-Ife, Nigeria

|

| |

|

5.3. Bivariate Statistical Correlations of Ecotourism Cultural Landscape Variables and Significance Variables

5.3.1. Case 1: Positive Significance of the Three Ecotourism Cultural Landscapes

Table 9a. Contingency table for Most Visually Accessible Place (desired to see) and Most Perceived as a Place of Honor and Fear of the Selected Tourist

|

| |

|

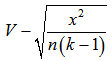

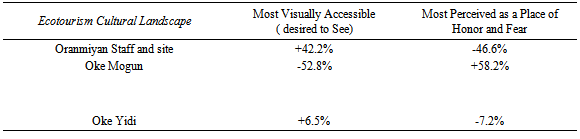

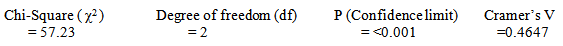

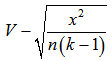

The Table value of χ2 is 13.816 and therefore much less than the calculated value which is 57.23 implying the rejection of null hypothesis 1, Ho1, stating that there is no (positive) significant relationship between types of ecotourism cultural landscapes and the memory spirit they embody. The conclusion is that there is significant relationship between types of ecotourism cultural landscapes and their embodied positive memory spirit.Cramer’s V (V) is used to determine Correlation from contingency tables when the number of rows and columns are not equal. The formula shows χ2 as Chi-square, n as Total number of observations and k as Number of rows or columns, whichever is smaller[25].

The Table value of χ2 is 13.816 and therefore much less than the calculated value which is 57.23 implying the rejection of null hypothesis 1, Ho1, stating that there is no (positive) significant relationship between types of ecotourism cultural landscapes and the memory spirit they embody. The conclusion is that there is significant relationship between types of ecotourism cultural landscapes and their embodied positive memory spirit.Cramer’s V (V) is used to determine Correlation from contingency tables when the number of rows and columns are not equal. The formula shows χ2 as Chi-square, n as Total number of observations and k as Number of rows or columns, whichever is smaller[25].  Pearson Chi-square is calculated as[26]:

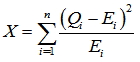

Pearson Chi-square is calculated as[26]: whereΧ2 = Pearson's cumulative test statistic;Oi = an observed frequency;Ei = an expected (theoretical) frequency, asserted by the null hypothesis;n = the number of cells in the table.

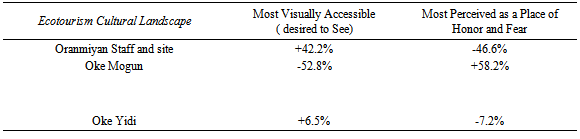

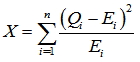

whereΧ2 = Pearson's cumulative test statistic;Oi = an observed frequency;Ei = an expected (theoretical) frequency, asserted by the null hypothesis;n = the number of cells in the table.Table 9b. Percentage Deviations

|

| |

|

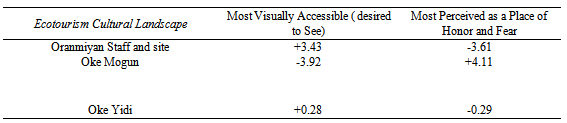

Table 9c. Standardized Residuals

|

| |

|

At 0.95Confidence limit and 0.0722 Standard Error, Lambda for Predicting Memory Significance of Ecotourism Cultural Landscape is 0.4206 and Estimated Probability of Correct Prediction when predicting Significance of Ecotourism Cultural Landscapes.

5.3.2. Case 2: Negative Significance of the Three Ecotourism Cultural Landscapes

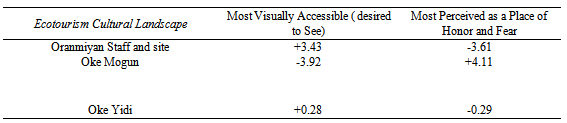

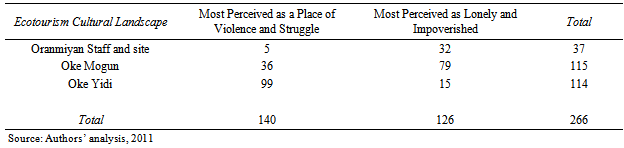

Table 10a. Contingency table for Most Perceived as a Place of Violence and Struggle and Most Perceived as Lonely and Impoverished of the Selected Tourist Sites in Ile-Ife, Nigeria

|

| |

|

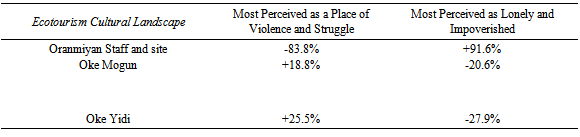

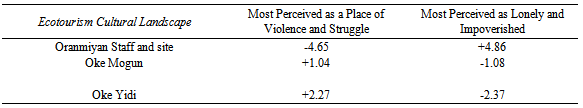

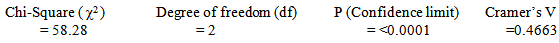

The Table value of χ2 is 13.816 and therefore lesser than the Calculated value which is 58.28 implying the rejection of null hypothesis 2, Ho2, stating that there is no (negative) significant relationship between types of cultural landscapes and the memory spirit they embody. The conclusion is that there is significant relationship between types of cultural landscapes and their embodied negative memory spirit. is 0.7245. Cramer’s V (V) and Pearson Chi-square formulae cited in Case 1 are equally applicable.

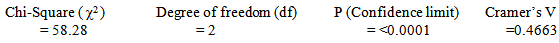

The Table value of χ2 is 13.816 and therefore lesser than the Calculated value which is 58.28 implying the rejection of null hypothesis 2, Ho2, stating that there is no (negative) significant relationship between types of cultural landscapes and the memory spirit they embody. The conclusion is that there is significant relationship between types of cultural landscapes and their embodied negative memory spirit. is 0.7245. Cramer’s V (V) and Pearson Chi-square formulae cited in Case 1 are equally applicable. Table 10b. Percentage Deviations

|

| |

|

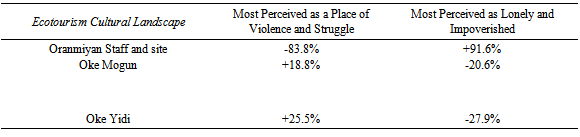

Table 10c. Standardized Residuals

|

| |

|

At 0.95 Confidence limit and 0.0702 Standard Error, Lambda for Predicting Memory Significance of Cultural Landscape is 0.3828 and Estimated Probability of Correct Prediction when predicting Significance of Cultural Landscape is 0.7052[27].

5.3.3. Case 3: Positive and Negative Significance of the Three Ecotourism Cultural Landscapes

Table 11a. Contingency Table for Perception as Most Source of Wonder and Interest and A Place of Man’s Inhumanity to Man of the Selected Tourist Sites in Ile-Ife, Nigeria

|

| |

|

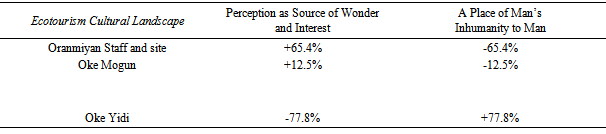

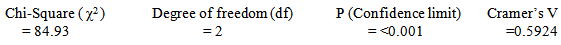

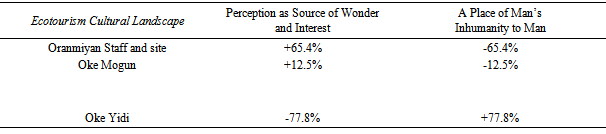

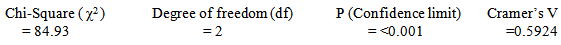

The Table value of χ2 is 13.816 and therefore lesser than the Calculated value which is 84.93 implying the rejection of null hypothesis 3, Ho3, stating that there is no (positive and negative) significant relationship between types of ecotourism cultural landscapes and the memory spirit they embody. The conclusion is that there is significant relationship between types of cultural landscapes and their embodied memory spirit both positive and negative Cramer’s V (V) and Pearson Chi-square formulae cited in Case 1 are equally applicable.

The Table value of χ2 is 13.816 and therefore lesser than the Calculated value which is 84.93 implying the rejection of null hypothesis 3, Ho3, stating that there is no (positive and negative) significant relationship between types of ecotourism cultural landscapes and the memory spirit they embody. The conclusion is that there is significant relationship between types of cultural landscapes and their embodied memory spirit both positive and negative Cramer’s V (V) and Pearson Chi-square formulae cited in Case 1 are equally applicable.Table 11b. Percentage Deviations

|

| |

|

Table 11c. Standardized Residuals

|

| |

|

At 0.95 Confidence limit and 0.0748 Standard Error, Lambda for Predicting Memory Significance of Cultural Landscape is 0.5207 and Estimated Probability of Correct Prediction when predicting Significance of Cultural Landscape is 0.7603. Bryman and Cramer (1997) suggest that 0.40 to 0.69 is a modest association while 0.70 to 0.89 is a high association. The Chi-square, Cramer’s V, Lambda and Estimated Probability tests clearly show association between types of cultural landscapes and the memory spirits that they evoke in all the tested pairs of positive significance (Case 1), negative significance (Case 2) and both combined (Case 3).

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

The symbolic value of the built environment and significant urban ecotourism cultural landscape and their elements in particular make them the physical documentation of past memorable events. The pains or gains, pleasures or punishments, life or death associated with such places create a constant re-echoing of the events and their outcomes in the memory of humankind. In the case of Ile-Ife, the memory of Oke Yidi is associated with pain and loss, Oke Mogun is an emblem of humankind’s craving for worship and its associated awe and sacredness while Oranmiyan Staff and site document the wonder of creation and ancestral spirit. The study has established relationships between types of ecotourism cultural landscapes and particular associated memory spirits. On the whole, place and memory are significantly connected and place is a solidified time in space.In view of this, the result of the study suggests that the three urban cultural landscapes and their elements should be promoted as Ecotourism Attraction Centres to tap their vast economic values and turn their associated memorable pains and pleasures into gains. This is definitely a duty for urban and landscape designers.

References

| [1] | Carmona, M., Heath, T., Oc, T., and Tiesdell, S. (2003) “Public Places-Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design” Oxford: Architectural Press. |

| [2] | Wyly, E.K. (2007) “Sense of Place” Urban Studies 200, Cities, November Accessedfromhttp://www.geog.ubc.ca/¬ewyly/u200/place.pdf. |

| [3] | Lynch, K. (1960) “The Image of the City” Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. |

| [4] | Knoz, P. and Pinch S. (2000) “Urban Social Geography: An introduction” Harlow: Prentice Hall. |

| [5] | Langenbach, R. (1984) “Continuity and Sense of Place: The Importance of the Symbolic Image” in Freeman, H. (ed.) Mental Health and the Environment. Great Britain: Churchill Livingstone. |

| [6] | Rossi, A. (1982) “The Architecture of the City” Cambridge MA: Mass. Press. |

| [7] | Swain, T. (1993) “A Place for Strangers” Cambridge University Press p . 39 |

| [8] | Malpas, J.E. (1999) “Place and Experience: A Philosophical Topography” Cambridge: University Press p.3 |

| [9] | Nuttall, M. (1993) “Place, Identity and Landscape in North-West Greenland” in Gavin D. Flood (ed) Mapping Invisible Worlds, Cosmos, Yearbook of the Traditional Cosmology Society, Edinburgh University Press pp 75-88. |

| [10] | Sheldrake, P. (2001) “Spaces for the Sacred: Place, Memory and Identity” Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University. |

| [11] | Till, K.E. (2005) “The New Berlin: Memory, Politics, Place. University of Minnesota Press. |

| [12] | Kaelber, L. (2007) “New Analyses of Trauma, Memory, and Place in Berlin and Beyond, A Review Essay”. Canadian Journal of Sociology Online May-June. |

| [13] | Tumarkin, M. (2005) “Traumascapes: The Power and Fate of Places Transformed by Tragedy” Melbourne University Press. |

| [14] | Jordan, J.A. (2006) “Structures of Memory: Understanding Urban Change in Berlin and Beyond” Stanford University Press. |

| [15] | Rapoport, Amos (1977) “Human Aspects of Urban Form: Towards a Man-Environment Approach to Urban Form and Design” Oxford, New York, Toronto, Sydney, Paris Frankfurt: Pergamon Press. |

| [16] | Vogt, E.Z. (1968) “Some Aspects of Zanacantan Settlement Patterns and Ceremonial Organization” in K.C. Chang (ed.) Settlement Archaeology, Palo Alto, California National Press pp. 154-173. |

| [17] | Obateru, O.I. (2003) “The Yoruba City in History: 11th Century to the Present” Ibadan, Nigeria: Penthouse Publication (Nig). |

| [18] | Eades, J.S. (1980) “The Yoruba Today” Cambridge University Press. |

| [19] | Embassy of the Federal Republic of Nigeria and GlobeScope, Inc. (2004) “About Nigeria” available athttp://www.2millionprayersfornigeria.org. |

| [20] | Globescope, Inc. (2004). History and People: Nigeria. Available athttp://www.nigeriaembassyusa.org/history.shtml |

| [21] | Ojo, A. (1966) “Yoruba Culture” London University Press pp. 194-195. |

| [22] | Bascom, W. (1969) “The Yoruba of Southwestern Nigeria” New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston pp. 9-11 |

| [23] | Mumford, L.(1961) “The City in History” Penguin Books pp. 104-105 |

| [24] | Johnson, S. (1969) “The History of the Yorubas” Lagos: C.S.S. Press, p. 146 |

| [25] | Székely, G. J. Rizzo, M. L. and Bakirov, N. K. (2007). "Measuring and testing independence by correlation of distances", Annals of Statistics, 35/6, 2769–2794. |

| [26] | Greenwood, P.E., Nikulin, M.S.(1996). A guide to chi-squared testing, J.Wiley, New York |

| [27] | Krzanowski, W. J. (1988) Principles of Multivariate Analysis: A User's Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. |

The Table value of χ2 is 13.816 and therefore much less than the calculated value which is 57.23 implying the rejection of null hypothesis 1, Ho1, stating that there is no (positive) significant relationship between types of ecotourism cultural landscapes and the memory spirit they embody. The conclusion is that there is significant relationship between types of ecotourism cultural landscapes and their embodied positive memory spirit.Cramer’s V (V) is used to determine Correlation from contingency tables when the number of rows and columns are not equal. The formula shows χ2 as Chi-square, n as Total number of observations and k as Number of rows or columns, whichever is smaller[25].

The Table value of χ2 is 13.816 and therefore much less than the calculated value which is 57.23 implying the rejection of null hypothesis 1, Ho1, stating that there is no (positive) significant relationship between types of ecotourism cultural landscapes and the memory spirit they embody. The conclusion is that there is significant relationship between types of ecotourism cultural landscapes and their embodied positive memory spirit.Cramer’s V (V) is used to determine Correlation from contingency tables when the number of rows and columns are not equal. The formula shows χ2 as Chi-square, n as Total number of observations and k as Number of rows or columns, whichever is smaller[25].  Pearson Chi-square is calculated as[26]:

Pearson Chi-square is calculated as[26]: whereΧ2 = Pearson's cumulative test statistic;Oi = an observed frequency;Ei = an expected (theoretical) frequency, asserted by the null hypothesis;n = the number of cells in the table.

whereΧ2 = Pearson's cumulative test statistic;Oi = an observed frequency;Ei = an expected (theoretical) frequency, asserted by the null hypothesis;n = the number of cells in the table. The Table value of χ2 is 13.816 and therefore lesser than the Calculated value which is 58.28 implying the rejection of null hypothesis 2, Ho2, stating that there is no (negative) significant relationship between types of cultural landscapes and the memory spirit they embody. The conclusion is that there is significant relationship between types of cultural landscapes and their embodied negative memory spirit. is 0.7245. Cramer’s V (V) and Pearson Chi-square formulae cited in Case 1 are equally applicable.

The Table value of χ2 is 13.816 and therefore lesser than the Calculated value which is 58.28 implying the rejection of null hypothesis 2, Ho2, stating that there is no (negative) significant relationship between types of cultural landscapes and the memory spirit they embody. The conclusion is that there is significant relationship between types of cultural landscapes and their embodied negative memory spirit. is 0.7245. Cramer’s V (V) and Pearson Chi-square formulae cited in Case 1 are equally applicable.  The Table value of χ2 is 13.816 and therefore lesser than the Calculated value which is 84.93 implying the rejection of null hypothesis 3, Ho3, stating that there is no (positive and negative) significant relationship between types of ecotourism cultural landscapes and the memory spirit they embody. The conclusion is that there is significant relationship between types of cultural landscapes and their embodied memory spirit both positive and negative Cramer’s V (V) and Pearson Chi-square formulae cited in Case 1 are equally applicable.

The Table value of χ2 is 13.816 and therefore lesser than the Calculated value which is 84.93 implying the rejection of null hypothesis 3, Ho3, stating that there is no (positive and negative) significant relationship between types of ecotourism cultural landscapes and the memory spirit they embody. The conclusion is that there is significant relationship between types of cultural landscapes and their embodied memory spirit both positive and negative Cramer’s V (V) and Pearson Chi-square formulae cited in Case 1 are equally applicable. Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML