-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Tourism Management

p-ISSN: 2326-0637 e-ISSN: 2326-0645

2013; 2(A): 34-42

doi:10.5923/s.tourism.201304.04

Community Participation in Ecotourism: The Case of Bobiri Forest Reserve and Butterfly Sanctuary in Ashanti Region of Ghana

Ishmael Mensah1, Adofo Ernest2

1Department of Hospitality and Tourism Management, University of Cape Coast, Ghana

2Wildlife Division of Forestry Commission, Kumasi, Ghana

Correspondence to: Ishmael Mensah, Department of Hospitality and Tourism Management, University of Cape Coast, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Community participation which is a bottom-up approach by which communities are actively involved in projects to solve their own problems, has been touted by various stakeholders as a potent approach to ecotourism development since it ensures greater conservation of natural and cultural resources, empowers host communities and improves their socio-economic well-being. While many ecotourism projects have been developed in or near protected areas such as forest reserves, such projects sometimes exclude the local communities who depend on the natural resources in those areas. The major objective of this study was to investigate the nature and extent of participation of local communities in ecotourism development and management in the Bobiri Forest Reserve and Butterfly Sanctuary (BFRBS). Data for the study was collected from residents, members of traditional councils and members of forest management committees of the three communities adjoining the forest reserve namely Krofofrom, Kubease and Nobewam. Results of the study indicate that community involvement is elusive to a greater majority of the people and this is attributed to the low level of the forest-fringe communities’ involvement in the project though some community members had derived modest benefits. The communities can therefore be placed at the level of induced participation on Tosun’s (1999) typology which tallies with degrees of tokenism on Arnstein’s (1969) typology. The study has both policy and research implications relating to the achievement of sustainable tourism development at the host community level.

Keywords: Community Participation, Ecotourism, Development, Local, Project

Cite this paper: Ishmael Mensah, Adofo Ernest, Community Participation in Ecotourism: The Case of Bobiri Forest Reserve and Butterfly Sanctuary in Ashanti Region of Ghana, American Journal of Tourism Management, Vol. 2 No. A, 2013, pp. 34-42. doi: 10.5923/s.tourism.201304.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Ecotourism is a form of tourism widely considered as an opportunity for local people to derive positive socio-economic benefits from tourism development whilst conserving forests. According to[1], rural ecotourism development can help sustain viable rural communities and at the same time meet the needs of a new breed of tourists. This is because unlike conventional tourism, ecotourism thrives in relatively untouched natural environments commonly found in rural areas and does not make huge demands on investments in facilities and infrastructure.Also, in the area of forest conservation and management, community involvement or participation in ecotourism development has become a viable tool aside tradi tional methods such as law enforcement, control of timber extraction and preservation of endangered species. Thus community participation in ecotourism development could be seen as both a conservation and developmental tool. Drumm[2] defines community participation in ecotourism development as ‘ecotourism programs, which take place under the control and with the active participation of local people who inhabit or own a natural attraction’. Through the involvement of host communities, tourism can generate support for conservation among such communities as long as they derive some benefits[3]. Forests in Ghana are gradually disappearing. There was a two percent (135, 000 ha) loss of forest annually from 1990 to 2000 in Ghana[4]. In view of this there have been some interventions by both the Forestry Commission as well as Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) such as the Nature Conservation Research Centre (NCRC) aimed at promoting the conservation of forests through community participation in ecotourism development and management in some forest-fringe communities such as those around the Bobiri Forest Reserve and Butterfly Sanctuary (BFRBS).

1.1. The Context

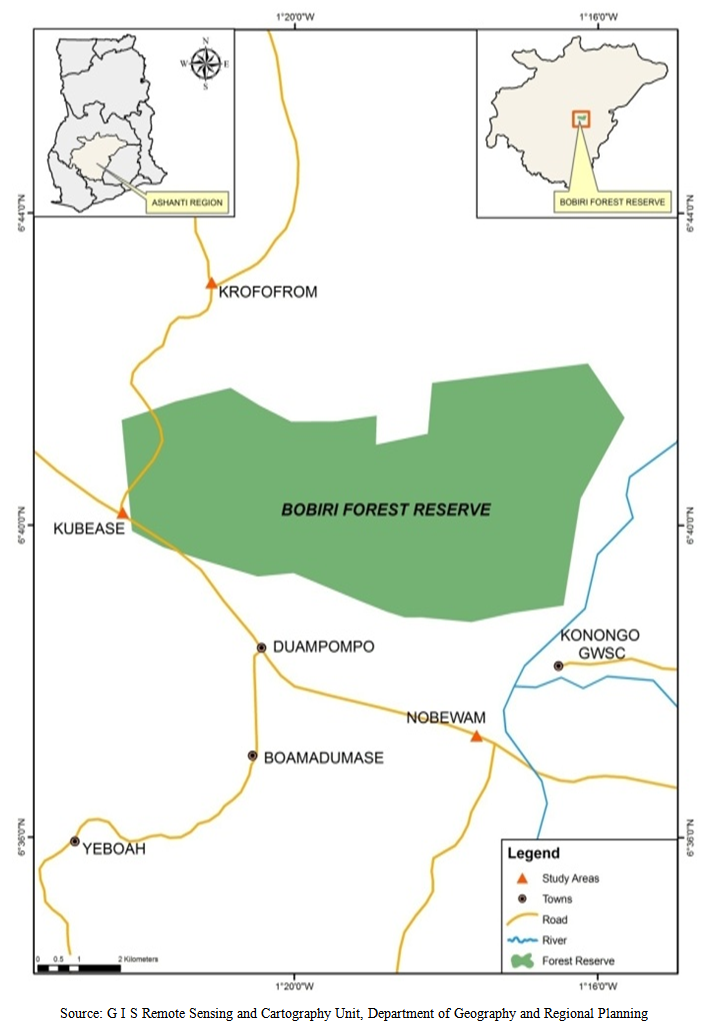

- BFRBS is one of the ecotourism sites designated by the Forestry Research Institute of Ghana (FORIG). Covering an area of 54.6 sq. Km (21.1 sq. Miles), it is the largest reserve in terms of total land area, administered by FORIG and one of the most beautiful forest reserves in West Africa. The reserve was created in 1939 when it was still an unexploited primary forest and falls within the Tropical Moist Semi-Deciduous Forest Zone. It lies between latitude 60 40’’ and 60 44’’ north of the equator and longitudes 10 15’’ and 10 22’’ west of the Greenwich. It hosts the Bobiri Forest Arboretum with about 100 indigenous tree species, 120 bird species and the Bobiri Butterfly Sanctuary with about 340 butterfly species as well as the Bobiri Guest House. The BFRBS is also rich in biodiversity, with 80-100 plants species per acre.

| Figure 1. Map of Bobiri Forest Reserve Showing the Study Areas. |

2. Conceptual Framework and Literature Review

- This section looks at the typologies of community participation as well as a review of the literature on rationale and benefits of community participation in ecotourism development.

2.1. Typologies of Community Participation

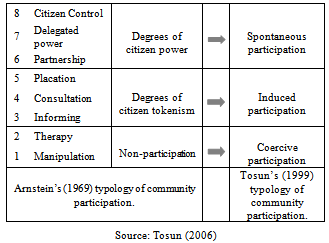

- The concepts of community involvement andcommunication participation which are one and the same thing, have received considerable academic interest. However, Arnstein’s[12] seminal work, Ladder ofParticipation has often served as a useful reference point. Arnstein[12] recognized that there are different levels of citizen participation, ranging from manipulation or therapy of citizens, where participation is a sham, through consultation, to citizen control regarded as genuine participation. The ladder of participation identifies eight levels of citizen participation (Figure 2). According to[12], citizen participation is the redistribution of power that enables have-not citizens to be deliberately included in the developmental decision-making process. It is the “means by which they can induce significant social reform, which enables them to share in the benefits of the affluent society” [12]. In this definition of participation, the most important point is the degree of power distribution. Arnstein[12] has conceptualized the degree of citizen participation in terms of a ladder or typology of citizen participation comprising of eight levels, which are classified into three categories relative to the authenticity of citizen participation. While the lowest category represents non participation, the highest category refers to degrees of citizen power and the middle category indicates degrees of citizen tokenism. However, some of the criticisms leveled against Arnstein’s typology are that it was developed in the context of developmental studies in general and not related to a particular sector of an economy[13]; it does not specifically deal with tourism development[14]; and it provides misleading results within a developing country context[15]. Tosun’s[16] Model of Community Participation (Figure 2) however, is situated within the context of community participation in tourism development. It considers community participation as a categorical term that allows participation of people, citizens or a host community in their affairs at different levels (local, regional or national).

| Figure 2. Normative Typologies of Community Participation |

2.2. Rationale and Benefits of Community Participation in Ecotourism Development

- Simons[17] is of the opinion that involvement of a community in any ecotourism project is vital for the overall success of that project. Brohman[18] supports this assertion and advocates for community participation as a tool for solving the problems of ecotourism in developing countries. For community participation to meet the expectations of a local community,[13] observed that the local community needs to be part and parcel of the decision-making body through consultation by elected and appointed local government agencies or by a committee elected by the public specifically for developing and managing ecotourism in their locality. Participation of host communities in ecotourism development and management could range from the individual to the whole community, including a variety of activities such as employment, supply of goods and services, community enterprise ownership and joint ventures[19]. According to[20], it is important to note that community participation in decision-making is not only desirable but also necessary so as to maximize the socio-economic benefits of ecotourism for the community. It is widely acknowledged that through community participation, host communities can participate in the decision-making process ([21],[22],[23],[24]). Moreover, one of the key underlying principles of ecotourism is that local communities must participate in tourism decisions if their livelihood priorities are to be reflected in the way ecotourism is developed ([20]). Engaging host communities in the decision-making process makes the planning process more effective, equitable and legitimate, since those who participate are representatives of the whole community and therefore project collective interests as well as those of their own group[25]. Cater[26] identifies revenue sharing, entrepreneurship and employment as well as sale of tourist merchandise as the forms in which community involvement in ecotourism could manifest. Ecotourism is more beneficial to local communities because it is more labour intensive and offers better small-scale business opportunities[27]. Since ecotourism takes place in the community, it is thought to be one of the best placed sources of employment opportunities for local communities, including women and the informal sector ([23],[27]). Community participation provides employment opportunities, as small business operators take advantage of abundant natural and cultural assets available in communities in developing countries to produce ecotourism products and services, including handicrafts[27]. Tosun[22] stressed that community participation through employment in the tourism industry helps local communities not only to support development of the industry but also to receive economic and other benefits. Tosun[22] further emphasized that in many developing countries community participation through employment of people in the industry or through encouraging them to operate small scale businesses, helps local communities to get more economic benefits rather than just creating opportunities for them to have a say in decisions made on tourism development. Participation in tourism through employment has more direct impacts on the lives of poor households, it helps to curb poverty at the household level by diverting the economic benefits of tourism directly to the family level[20]. Mbaiwa and Stronza[28] in a study of ecotourism among indigenous communities in the Okavango Region in Botswana found out that ecotourism had become the main source of livelihood of the members of those communities. Traditional livelihood activities that damaged the environment such as hunting, gathering, livestock, and crop farming had been replaced by ecotourism. Also, in a comprehensive study of ecotourism in Belize by[29] they found out that, all the local communities benefited significantly from tourism in the protected areas nearby by selling handicrafts and by providing accommodation and other services to tourists. However,[30] in a study on pro-poor tourism in the Kakum National Park Area of Ghana found out that residents had modest direct socio-economic benefits from tourism and that they gained more from associated interventions than from tourism.Other benefits associated with community participation in ecotourism are; conservation of natural and cultural resources ([31],[32]); empowerment of host communities ([33],[1]); and tourists’ appreciation and understanding of local cultures[31].Despite the benefits associated with community participation, it is rarely found in developing countries[22]. Dei[21] reported of discontent in some communities surrounding the Kakum National Park, as a result of their exclusion from the operations of the park. Li[23], in a study on community decision-making participation in tourism development in Sichuan Province, China, pointed out that there was weak local involvement in the decision-making process yet local communities received satisfactory benefits from tourism. He therefore concluded that integration of local communities into the decision-making process is not a final goal in itself but only one of the many ways through which community participation can be achieved. Also, the mode of distribution of the benefits of ecotourism engenders unfairness and inequalities among stakeholders ([34],[35]. He et al.[35] in a study in China, found out that the majority of economic benefits in three key ecotourism sectors namely, infrastructural construction, hotels/restaurants and souvenir sales went to stakeholders outside the local community. Mowforth and Munt[34]have also estimated that the proportion of total gross revenues from ecotourism that stays in the host community to be as low as 10 percent in certain countries, including Bahamas and Nepal.

3. Methodology

- The target population for the study were the residents of the six communities that fringe BFBS. However, three communities namely Krofofrom, Kubease and Nobewam were purposively selected for this study because they are entry points to the BFBS. A combination of both probability and non-probability sampling procedures were employed. According to[26] a community is not a homogeneous construct which means that there will be marked discontinuities socially, sectorally, spatially and temporally. Therefore, the population of the three communities was divided into three categories and a sample drawn from each. The categories were chiefs and elders, committee members and the general public. Chiefs, elders and committee members were purposively selected whilst the general public was randomly selected. The sample size of 168 included 12 chiefs and elders, six committee members and 150 of the general public from the three communities. The questionnaire employed for the study was divided into five main sections namely socio- demographic characteristics of respondents, community awareness of ecotourism, level of community involvement, community involvement in forest reserve management and benefits of ecotourism to the communities. Fieldwork was undertaken in January, 2011 by administering the questionnaires to local residents in selected households. The questionnaire had to be administered because the majority of respondents had limited literacy and could not complete the questionnaires on their own. Traditional leaders were contacted in the chiefs’ palaces and permission sought from them before the fieldwork commenced. At the end of the fieldwork 168 residents were interviewed in the three communities. Data collected from the field was analyzed using the Statistical Product for Service Solution (SPSS) Version 16.

4. Findings

4.1. Socio-demographics Characteristics

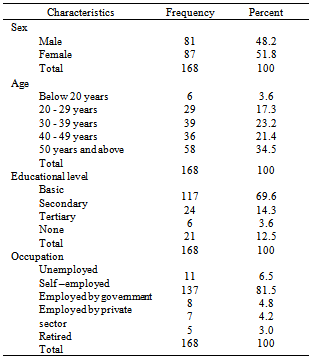

- Table 1 shows that out of the total of 168 respondents surveyed, there were slightly more females (51.8%). About one-third of the respondents (34.5%) were more than 50 years while the age group with the least number of people was those less than 20 years who accounted for 3.6% of the respondents. About 70% had acquired basic education 69.6%abanaand and only 3.6% had completed tertiary level education. There was therefore a general low level of education in the communities. The majority of respondents (81.5%) were self- employed with only 6.5% being unemployed. This could be due to the fact that the three communities are rural with the dominant economic activity being subsistence farming which is typical of forest-fringe communities.

4.2. Level of Community Awareness and Involvement in Ecotourism

- About 70% of respondents were aware of the existence of the BFRBS ecotourism project, an indication that residents of the three communities were largely aware of the ecotourism project. However, barely a quarter of respondents (25.6%) indicated that they knew about FOBF as shown in Table 2. The fact that a lot of local residents were not aware of FOBF, calls to question the efforts of FORIG at marshalling local support for ecotourism development so as to protect the forest reserve. In spite of the high awareness of the BFRBS ecotourism project, nearly half of respondents (49.4%) had never been to the project site.

|

| Figure 3. Areas of Community Involvement |

|

|

|

4.3. Benefits of Ecotourism to the Communities

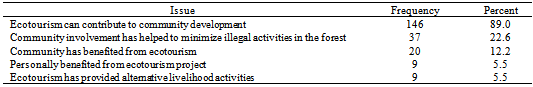

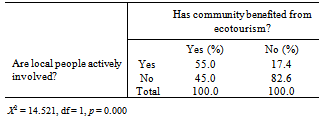

- The benefits derived from ecotourism at BFBS reflect the tokenism proposed by[16]. Only 12.2% of respondents indicated that their communities had benefited from the BFRBS ecotourism project whilst barely 9% of respondents indicated that they had personally benefitted (Table 4).This is against the background that 89% of respondents held the view that ecotourism could contribute to community development. The communities had high expectations of ecotourism as a tool for socio-economic development but in reality such expectations had not been met. The general dissatisfaction with the contribution of ecotourism to their socio-economic development could therefore stem from the fact that they had high expectations which had not been met.There was however a modicum of benefits derived by some members of the communities from ecotourism. For the 12.2% of respondents who indicated that their communities had benefitted from ecotourism at BFRBS, such benefits were conservation of the forest, prestige to the local communities, donation of books, sponsorship, provision of sign post, tourist information centre and employment.Some respondents also intimated that, some members of the communities were initially provided training in alternative livelihood activities such as tie-and-dye making, snail-rearing and bee-keeping which provided jobs to the local people to enable them to improve their well-being.

4.4. Community Participation and Perceived Benefits of Ecotourism

- A chi-square test at P ˂ 0.05 indicated a relationship between participation and perceived benefits of ecotourism as shown in Table 5. For those respondents who perceived their communities as having benefited from ecotourism, 55% of them also held the view that local people were actively involved in the ecotourism project compared to 45% who held a contrary view that local people were not involved. Also, for those who thought ecotourism had not benefitted their communities, only 17.4% of them held the view that local people were actively involved whereas 82.6% held the opposite view that local people were not actively involved. Therefore the greater the participation of communities in ecotourism development, the more positive the perceived benefits of ecotourism and vice versa.

|

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- This study investigated the nature and extent of participation of local communities in ecotourism development and management in the BFRBS. The findings have established that there is high level of awareness of the ecotourism project in the forest-fringe communities. Also, the study revealed that there is a low level of community participation in the ecotourism project in the BFRBS. The majority of people in the forest-fringe communities of Krofofrom, Kubease and Nobewam were not actively involved in almost all the activities of the project. They were only informed about the project which shows that there is one-way flow of information without feedback. The study found out that the level of participation of the communities in the ecotourism project and in the management of the forest reserve to be at the degree of tokenism in Arnstein’s[12] typology of community participation which is congruent with induced participation in Tosun’s[16] topology. The study further revealed that the communities around the BFRBS had not benefited much from the ecotourism project due to the low level of community participation in the project except for a modicum of benefits such as donation of books, sponsorship, tourist information centre and employment of some local people.There is the need for consensus among various stakeholders including the Forestry Commission, FORIG, NCRC and the communities to ensure that the communities are fully represented on key committees tasked with the management of ecotourism in the BFRBS to promote community participation in ecotourism development among forest fringe communities. There should also be fair representation of communities and other identifiable interest groups on such committees.It is also important that management of the BFRBS ensure that there is free flow of information between them and the local communities. In order to ensure two-way flow of information between them and the local communities, mechanisms should be put in place to ensure feedback from the local communities through the medium of community durbars and fora to help quell any rumour concerning any decision taken by the authorities. An essential ingredient in community participation is capacity-building. For local people to be in a better position to make meaningful contribution towards the development and management of ecotourism, they must have certain key competencies. Therefore, the Forestry Commission, FORIG and other stakeholders should put in place measures to build the capacity of the local people living around forest reserves through the provision of training in management, hospitality, tour guiding and other employable skills for the tourism industry. They should also facilitate access to credit by local entrepreneurs to enable them to partake in the socio- economic fortunes of the project. Also, training of local people in alternative livelihood activities such as art and craft making, bee keeping, mushroom growing and grass cutter rearing should not be seen as an end in itself but should be integrated with the needs of the tourism industry so that there will be a ready market for the products and services of trainees so as to ensure the sustainability of such interventions.Results of the study indicate that one area of concern in community participation in the BFRBS ecotourism project is revenue-sharing. It is imperative that revenue is shared between resource managers and land owners in a transparent and fair manner. The revenue entitlements of communities should be made known to the general public and should be managed by a well-constituted committee which should be given the authority to use the community’s share of the revenue for infrastructural development and other social interventions. Finally, future studies on community participation in ecotourism development should focus on the obstacles to full integration and involvement of communities. This will help find answers to what accounts for the current low levels of community participation in ecotourism development and management in some communities. Such findings will inform a well-conceived policy intervention to address the problem.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML