-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Textile Science

p-ISSN: 2325-0119 e-ISSN: 2325-0100

2014; 3(1A): 6-14

doi:10.5923/s.textile.201401.02

Colour and Fastness Properties of Natural Dyed Wool for Carpets: Effect of Chemical Wash

Shruti Gupta1, Deepali Rastogi2

1Department of Textile Design, National Institute of Fashion Technology, Himachal Pradesh, 176001, India

2Department of Fabric and Apparel Science, Lady Irwin College, New Delhi, 110001, India

Correspondence to: Shruti Gupta, Department of Textile Design, National Institute of Fashion Technology, Himachal Pradesh, 176001, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

In the present study the effect of chemical washing on colours obtained by natural dyes on wool was studied. Colour values of natural dyed wool were determined in terms of L*a*b* values. Samples were assessed in terms of the colour fastness to rubbing, washing and light. A wide gamut of colours were obtained after dyeing of wool with different natural dyes and mordants. Chemical washing brings about significant changes in the colour and fastness properties of natural dyed wool yarn. The colours however, remain stable after chemical washing. It is therefore possible to select a gamut of colours from the shade cards of natural dyed wool yarns.

Keywords: Natural dyes, Wool yarns, Chemical Washing, Colour Values, Fastness Properties

Cite this paper: Shruti Gupta, Deepali Rastogi, Colour and Fastness Properties of Natural Dyed Wool for Carpets: Effect of Chemical Wash, International Journal of Textile Science, Vol. 3 No. 1A, 2014, pp. 6-14. doi: 10.5923/s.textile.201401.02.

1. Introduction

- The word wool was called “wull” in old English, “wullo” in Teutonic, and “wlna” in Pre- Teutonic days. Wool is the fibre from the fleece of domesticated sheep. It is a natural, protein, multicellular, staple fibre. The fibre density of wool is 1.31g/cm³, which tends to make wool a medium weight fibre [1].Dyed wool is customarily used for the pile. This can vary enormously in quality. Early safavid rugs use soft fleecy wool of the highest quality, while Turkish and Caucasian village rugs generally use fairly coarse, harsh wool. Silk is used for more sumptuous rugs and is rarely encountered in village rugs, although it is used in small quantities to embellish Turkoman, Caucasian and Turkish rugs. Cotton is frequently used for details in early safavid and Indian rugs, in later Ghiordes rugs, Turkoman Saryk rugs and in Ottoman Bursa rugs. Usually it is undyed, but a blue dyed cotton is used in Bursa rugs. Silver and silver-gilt thread wrapped on a silk core is found brocaded in some safavid rugs and in later Turkish count rugs like Hereke and Koum Kapou [2]. Basically wool, like all other hairs, animal horns, and finger-nails, is composed of a special protein called Keratin, which differs from others on account of its high-sulphur content. Raw wool, however, may contain between 30 and 70 per cent of impurities [3].Wool undergoes various wet treatments both before and after dyeing, that concern the dyer. Efficient preparatory treatments of the material are the key to good dyeing’s, whilst the success of subsequent wet treatments is generally reliant on the proper selection and application of suitable dyes. Since the conditions of post-dyeing processes are usually more severe than those of any normal aftercare treatments, dyeing’s that have proved satisfactory during the processing will possess more than adequate fastness properties for consumer use.Technical requirements also depend on whether the fibre needs to be dyed as loose fibre (‘loose stock’), combed wool in the form of an untwisted strand of parallel fibres from the combing operation (‘top’), yarn or fabric. With each type of substrate particular criteria have to be met in order to produce the required quality of colour, and this is usually achieved through variations in the dyeing conditions.Woven fabric requires both very level dyeing and excellent fastness properties, the latter being necessary to withstand the remainder of the finishing processes. These range from the removal of spinning oils by a scouring treatment of a few minutes duration in a weakly alkaline detergent solution to more severe treatments in steam (decatising), boiling water (crabbing and potting), chemical treatments (setting) and mechanical treatments of wet fabric (milling), all of which impart particular characteristics required for the end use of the wool fabric. It may be necessary also to treat the dyed fabric with 5% sulphuric acid solution, followed by drying and baking (carbonizing), to facilitate the removal of burrs. None of these treatments will be encountered by the fabric after it leaves the factory and they are all more severe than conditions encountered in normal aftercare [4]. Dyes used for dyeing of wool are acid, basic, chrome, metal-complex and reactive dyes [5]. Many developing countries already have long traditions of natural dye use and possess the raw materials to extract dyes. Natural dyed products thus represent a good opportunity for value-added exports from countries that already are world leaders in textile manufacturing [6].Mordants are considered to be an integral part of the natural dyeing process. It is believed that it is not possible to dye with natural dyes in the absence of mordants [7]. The term ‘Mordant’ has been derived from the Latin word ‘mordere’, meaning ‘to bite’ or to take hold of. Mordants are chemicals in the form of metal salts which are needed to create an affinity between the fibre and pigment, thus allowing certain dyes with no affinity for the fibre to be fixed on it. If the dye is capable of dyeing the fibre directly, then the mordant helps to produce faster shades by forming an insoluble compound of mordant and dyestuff with the fibre itself [8]. Mordanting can be done at three stage namely : Prior to dyeing called premordanting, at the time of dying called simultaneous or co- mordanting and after the completion of dyeing called as post mordanting.The use of natural dyes can be traced back to antiquity and oriental rugs in the museums of all over the world happen to be living evidence of the ancient art of ‘natural dyes’ mystery and prestige, employing vegetable, animal and mineral sources. The unique artistry and colour harmonies of each rug depicted the cultural and historic tradition of thousands of years. The entire dyeing process, from mordanting the woollen skeins to make them respective to colour, to extraction of colour and dyeing varied from local conditions, different size lots and source of the colouring matter, contributing to many a different shade called ‘abrash’ a deficit, which was however found to be desirable quality in rugs made with traditional dyes. The intrinsic beauty of a rug, improved upon age with maturing of colour and softening of fibres on the pile surface. Development of artificial colours with the advent of chrome synthetic dyes gave out solid areas of colour unrelieved by abrash and retained a harsh brightness in the shades. This was accentuated by the rise in demand and pressure of increased of orders from the western importing countries enforcing compromise on indigenous patterns and doing away with natural dyes, to speed up production. However, the concept of colour development of carpets is subject to change from time to time as per the taste and trends prevalent in the buyer countries. The present demand into develop colours using natural dyes with solidity of shades without any variation and abrash [9]. The process consists of, firstly, a chlorinating agent which causes modification of the surface scales on wool. The ‘rounding’ of the scales produces lusture. The rate of modification is very pH dependent. Under acidic conditions free chlorine is liberated and the reaction is so rapid that only the surface will be affected. Under alkaline conditions the reaction is slower and more easily controlled. Secondly, sulphuric acid is used which helps in removing excess dye from the fibre, hence imparting good fastness. Thirdly, sodium hydroxide is used which swells the wool fibre. This action could be described as ‘softening up’. Lastly, acetic acid is used to neutralize the wool fibre so that fibre do not decompose. The major objective is to achieve a quantified, reliable method of chemical washing, weather manual or in existing mill machinery, which will give reproducible results as well as silkiness, lusture and colour modification [10].Chemical washing is an important process in carpet making which is given to impart lusture, soft feel and to prevent felting. However, not all dyes can withstand such a severe treatment. Natural dyes pose further problem as most of them are extremely sensitive to change in pH.In this study an attempt has been made to observe and standardize the colour changes in natural dyed wool on subjecting to chemical washing.

2. Materials and Methods

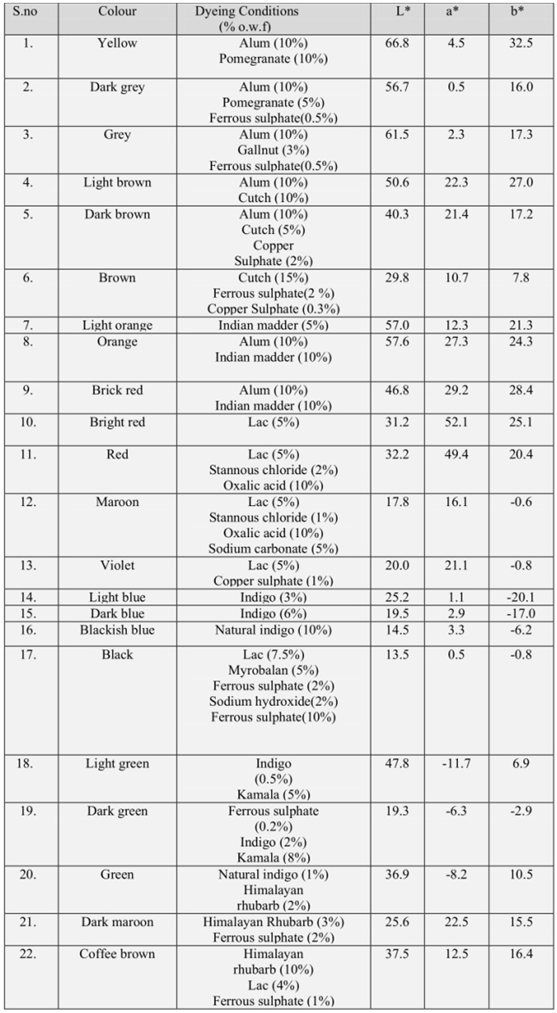

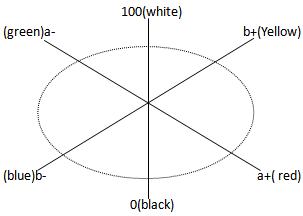

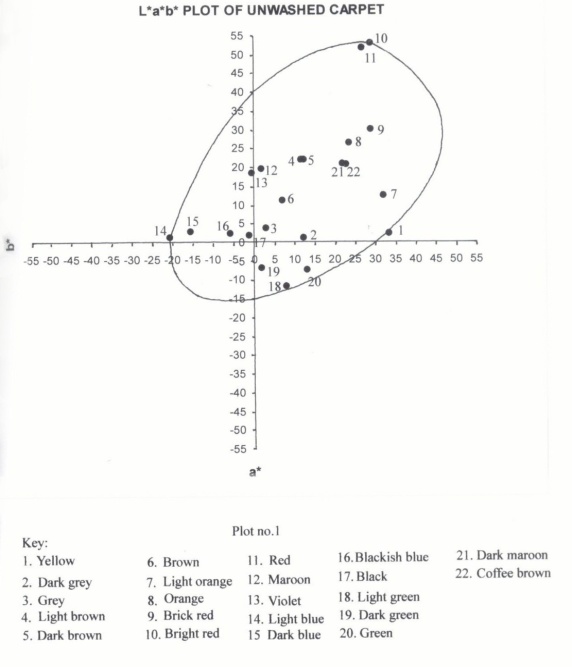

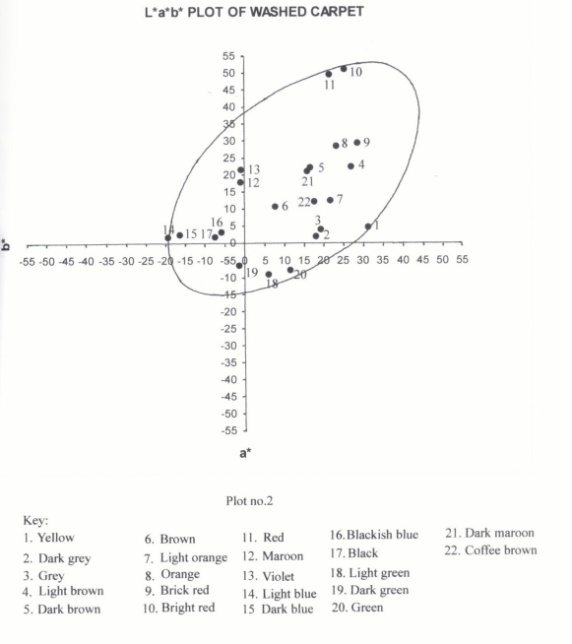

- The study was carried out to see the effect of chemical washing on colours obtained by natural dyes on wool. Samples were assessed in terms of the colour fastness to rubbing, washing and light. Colour values of natural dyed wool were determined in terms of L*a*b* values. All the dyes were available in powder form and were obtained from Alps Industries Ltd., Sahibabad. The selected dyes were Pomegranate fruit rind (Punica granatum), Gall nuts (Quercus infectoria), Cutch (Acacia catechu), Indian madder (Rubia cardifolia), Lac dye (Luccifer lacca), Myrobalan (Terminalia chebula), Indigo (Indigoferra tintoria), Kamala (Mallotus philippensis), Himalayan Rhubarb (Rheum emodi).The chemicals used were Calcium hypochlorite (Bleaching powder), sulphuric acid, sodium hydroxide, acetic acid, oxalic acid, ammonia, sodium carbonate sandofix NITI (dye- fixing agent), lissapol N (non-ionic detergent), aluminium potassium sulphate (alum), tartaric acid, ferrous sulphate, stannous chloride. Scouring of wool yarn hanks was carried out with Non-ionic detergent at 60°C for 45 minutes. Mordanting was carried out at material liquor ratio of 1:20. It was done with: (a) alum and tartaric acid (b) ferrous sulphate and (c) copper sulphate. All the dyeing’s were carried out at a material to liquor ratio of 1:20. After dyeing the neutralization was done at room temperature for 20 minutes. Sodium hydroxide was added to the bath and dyed yarns were entered in it. The solution was drained, yarn was squeezed and washed. Soaping was done with lissapol at 60ºC for 20 minutes.Chemical washing to the carpets were given to impart the lusturous, silky features to the carpets. The solutions for chemical washing ware made with chlorination bath-26.6g bleaching powder/litre, Sulphuric acid solution-10 ml/litre, Sodium hydroxide solution-13.3g/litre, Acetic acid solution-9.3ml/litre.The dyed yarns were thoroughly rinsed with water and were subjected to the sequence of treatments: Dipping in chlorination solution for 15 minutes, Draining the solution and rubbing the yarns for 2 minutes, thorough washing of yarns with cold water, 3 dips in the sulphuric acid solution, Dipping in sodium hydroxide solution for 2-3 minutes, Thorough washing of yarns with water, Neutralizing by dipping the yarns in acetic acid solution, final washing of yarns with cold water.After dyeing the samples, it is necessary to determine their colour value according to a standard system of measurement. Colour is defined as the sensation which is created in the brain by a message stimulated by the impact of radiation of a particular wavelength (usually 400-700nm for visible light). In 1931 Commission International de Eclariage provided the CIE system for numerical specification of colour. In the study L*a*b* values of both chemical washed and unwashed samples were determined using the ACS spectrophotometer interfaced with an IBM-PC. The L*a*b* colour space or the An Lab colour space is a 3-D colour space which helps to measure colour by calculating the L* a* b* values of a colour. In this colour space, L* indicates lightness and darkness of samples. The values of L* range between 0 to 100. Value of 0 signifies hypothetical black and value of 100 signifies hypothetical white. a* and b* are the chromaticity co-ordinates. The significance of a*and b* value is:+ve values of a* signifies redness-ve values of a * signifies greenness +ve values of b* signifies yellowness-ve values of b* signifies blueness

| Figure 1. A diagram depicting the significance of L*a*b* values |

3. Results and Discussion

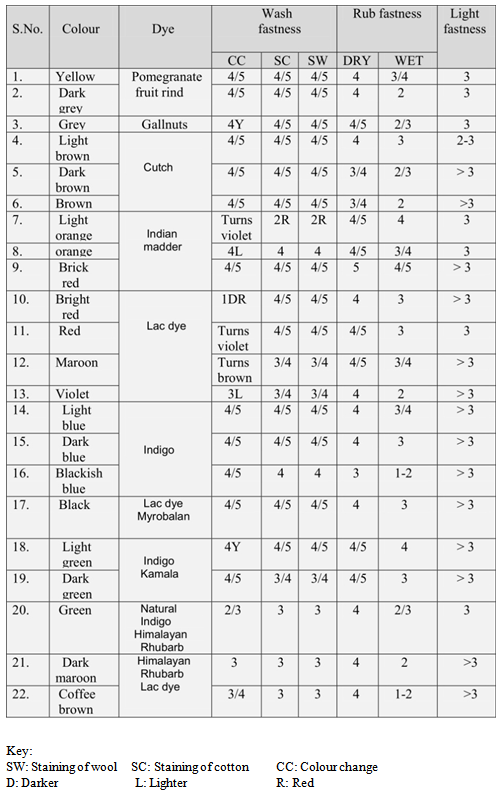

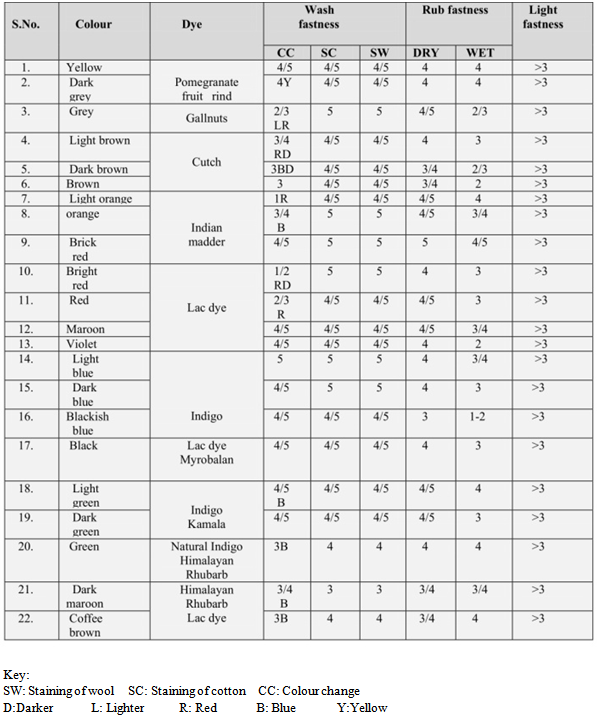

- The present research was conducted to study the effect of chemical washing on colour and fastness properties of natural dyed wool. A coloured good, during its use, may undergo colour change. The colour change can occur due to two reasons (a) the dye itself gets converted inside the fibre thereby getting converted into colourless or differently colour compound (b) It gets detached from the substrate.Wash fastness of the dyed samples was determined according to the ISO-2 method. The results obtained for the wash fastness of natural dyed wool are given in Table 1.Pomegranate fruit rind dyed samples showed very good wash fastness rating of 4/5, even after mordanting with ferrous sulphate.Samples dyed with gallnut showed good wash fastness but it turned a little yellow. Cutch and indigo dyed samples showed good fastness properties. The samples dyed with Indian madder turned violet in the case of light orange colour and there was staining on undyed wool and cotton.Lac dyed samples became redder and darker on washing. The samples turned violet and brown in the case of red and maroon colour respectively. The sample obtained by dyeing with a combination of lac and myrobalan dye was black in colour and showed good fastness rating of 4/5. Dyed samples obtained by a combination of indigo and kamala dye showed good fastness properties but samples obtained by a combination of indigo and himalayan rhubarb showed average wash fastness rating of 3/4. The samples obtained by dyeing with a combination of himalayan rhubarb and lac dye showed good wash fastness rating of 3/4 -4.The samples were tested for their fastness to light by placing the dyed samples in Xenon arc filament light fastness tester, Suntest CPS+. The light fastness of all the natural dyed samples are given in Table 1. All the dyed samples have shown good light fastness rating of 3 or above except in the case of cutch dyed sample which is light brown in colour which gave the rating of 2/3.The rub fastness of the dyed samples were tested in dry and wet conditions. The rub fastness of all the natural dyed samples are given in table 1.

|

|

| Graph 1. L*a*b* plot of unwashed Carpet |

| Graph 2. L*a*b* plot of washed Carpet |

|

4. Conclusions

- There has been an increasing interest in natural dyes as the people are becoming aware of ecological and environmental problems related to the use of synthetic dyes. Use of natural dyes cuts down significantly on the amount of toxic effluent resulting from the dye process. In the manufacture of carpets a chemical wash is given with a chlorinating agents, acids and alkalis. The dyed wool has to withstand these treatments. In the present research an attempt was made to study the effect of chemical washing on colour and fastness properties of natural dyed wool. The dyed samples were tested for their colour value and fastness properties, such as wash, rub, light. The results obtained from the study shows that a wide gamut of colours were obtained after dyeing of wool with different natural dyes and mordants. There was a change in colour after chemical washing. The colour change observed were pomegranate fruit rind and gallnuts dyed samples became lighter and yellower, cutch, lac, and Indian madder dyed samples became darker. All the samples dyed with combinations of dyes became darker and brighter after chemical washing. The wash fastness of natural dyed wool yarn in general was good for all the dyes ranging from 3/4-5. Chemical washing brings about significant changes in wash fastness properties of natural dyed wool yarn. The wash fastness of all the dyeings either improved or remained unaffected on chemical washing. The light fastness of most of the natural dyed samples before and after chemical washing was above 3.The dry rub fastness was good for all the dyes ranging from 4-4/5 but the wet rub fastness was not so good. After chemical washing the wet fastness improved in the case of pomegranate, indigo, lac, cutch and combination dyes. Chemical washing brings about significant changes in the colour values and fastness properties of natural dyed wool yarn. The colours however remains stable during subsequent washing. Thus, it can be concluded that carpets can be made successfully using natural dyed wool yarn.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML