-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2014; 4(6A): 19-27

doi:10.5923/s.sports.201401.03

Long-term Sport Development in Portuguese Futsal Players

João Serrano1, Shakib Shahidian1, Nuno Leite2

1School of Sciences and Technology, University of Évora, Évora Codex, Portugal

2Department of Sport Sciences, Exercise and Heath, University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro, Portugal

Correspondence to: João Serrano, School of Sciences and Technology, University of Évora, Évora Codex, Portugal.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Characterization of long-term athlete development of experts is a process that could identify the underlying mechanisms of excellence in sports and define the patterns that make it possible to reformulate the dynamic process of talent identification. The objective of the study was to identify differences in the long-term athlete development in three competitive levels of futsal players: expert, intermediate and non-expert. The participants filled out a questionnaire, based on retrospective information. The results showed significant differences among all competitive levels in the futsal starting age, in the inactivity period between seasons and in the time spent in training activities.

Keywords: Competitive level, Early specialization, Expertise

Cite this paper: João Serrano, Shakib Shahidian, Nuno Leite, Long-term Sport Development in Portuguese Futsal Players, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 4 No. 6A, 2014, pp. 19-27. doi: 10.5923/s.sports.201401.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In recent years numerous studies have been carried out with the aim of identifying the factors responsible for obtaining sport expertise [1]. Williams and Hodges [1] report that development of expertise is dependent on a complex set of factors which include hereditary, genetic and environmental factors, and within these, the most important factors are the influence of family members and coaches, as well as the individual motivation for practice. Usually, the term sport expert is associated with an athlete with competencies at an advanced stage of development, and one who makes more and faster decisions, as a result of a longitudinal process of acquisition and expression of differentiated sport skills [2]. Singer and Janelle [3] have analyzed various factors that influence acquisition and expression of high levels of sports performance. They have presented primary factors (genetic, psychological and sport preparation that is related to the quantity and quality of training) and secondary factors (context, socio-cultural - which includes family support and its influence on continued involvement in the sport, relative age and population density). Reilly et al. [4] have demonstrated the importance of anthropometric, physiological and psychological aspects, as well as mastery of specific technical skills in identification of talents in football, while Williams and Reilly [5] state that parental support, encouragement of the coaches, dedication and commitment to training, training conditions and significant opportunities for practice are fundamentals. Simon and Chase [6] maintain that 10 years of practice are needed to achieve expertise in individual sports. Ericsson et al. [7] conducted a research that supports this idea, however, they added the need for this practice to coincide with critical periods of biological and cognitive development, concluding that the sooner and the more specific the practice, the greater the possibilities for the athlete to achieve expertise. The studies of Ericsson et al. [7, 8] are the basis of the theory of deliberate practice which maintains that it is the number of hours of specific sport practice, associated with high levels of motivation that determines the level of performance in a sport. Côté et al. [9] suggest that there are key-periods in sport specialization, with an emphasis on the influence of participation in a wide range of activities, and not only in the sport with the greatest interest. This research team [9-11] presented the Developmental Model of Sport Participation (DMSP), which considers three stages of sport participation and development before reaching expertise: -sampling stage (6–12 years): children given the opportunity to sample a range of sports, develop a foundation of fundamental movement skills and experience sport as a source of fun and excitement; -specialization stage (13–15 years): when the child begins to focus on a smaller number of sports and, while fun and enjoyment are still vital; sport-specific emerge as an important characteristic of sport engagement; and -investment stage (16+ years): when the child becomes committed to achieving a high level of performance in a specific sport and the strategic, competitive and skill development elements of sport emerges as the most important. The most effective learning occurs through participation, in what they called deliberate practice. This form of practice requires effort, is not inherently enjoyable and is specifically designed to improve performance. Helsen et al. [12] found a positive linear relationship between the hours of practice and mastery of specific skills, which may play an important role as a predictive parameter. Furthermore, Baker et al. [13] showed that experts in field hockey, netball and basketball accumulated more hours in practice of specific sports than non-experts, finding on the one hand, that the number of training hours in each sport increases considerably, from the early stage to specialization, and on the other, that there is a significant negative correlation between the number of other activities and the number of hours required to achieve high performance in sports. Ward et al. [14] studied two groups of football players: expert and sub-expert players in a retrospective study and noted that the expert players who spent more time on decision-making activities during the games had higher levels of motivation and had greater parental support. They concluded that the diversity of activities practiced in the early stages of sports development, are more benefitial at the level of motor proficiency than the specific skills of the sports activity. Identification of talent in football, futsal or other sports is a constantly evolving process, whose dynamics have attracted the attention of several research teams. According to Reilly et al. [4], talent identification is a more complex process in team sports than in individual sports, referring, particularly in football, to the importance of external factors such as opportunity for practice, absence of injuries, quality of technical supervision provided by the coaches during the stages of development and also personal, social and cultural factors. Williams and Hodges [1] have identified practice and instruction as the key ingredients for athletes achieving success. One possible approach is through evaluation of the history of athletes with high performance levels, based on which one could identify the underlying mechanisms and define the patterns that make it possible to reformulate the process of talent identification. A review of the available information regarding the history of elite athletes reveals basically two lines of approach: on the one hand, there is the theory of deliberate practice (already presented above) and on the other hand, there is the theory of diversified practice (for example the studies of Baker et al. [2, 13, 15], that essentially contradicts the former, and which believes that, among several relevant variables, practicing non-specific sports activities, in which the dynamic of decision making is required, by athletes at the early stages of their physical and cognitive development, increases the skills necessary for the main sport, providing an active contribution with regard to psychomotor and multilateral development. This contribution is reflected in subsequent achievements in areas of specialization, facilitating intrinsic motivation and providing an environment conducive to acquisition of motor and physiological skills. They conclude that these athletes need fewer training hours in their specific sports activity to become experts.Several works have been published in order to help clarify this point. For example, the results obtained by Ward et al. [14] in analyzing the long-term development of high performance football players do not support the position of deliberate practice, while the results obtained by Leite et al. [16], with high performance athletes (in roller hockey, football, basketball and volleyball), value diversified practice, and not early specialization, as a decisive variable. Côté [17], examining the early stages of development of expert athletes, has also found that early specialization does not seem to be essential in order to achieve high performance in adult development stage. Memmert et al. [18] have reservations with regard to the theory of deliberate practice, questioning the transfer that may result from specific training in tactical creativity in team sports with ball. Memmert et al. [18] and Williams and Ford [19] maintain that practicing other forms of sports, with common characteristics to those of the main sport, especially in generic aspects of pattern recognition, anticipation and decision making, can partially replace some of the many hours of specific sport practice, required to obtain the expertise in team sports. Leite et al. [16] consider that these common features are related to repeated dynamics of decision-making during the game, within the context of a confined space that requires development of spatial pattern recognition skills with a high degree of physical fitness. They state, for example, that participation in different aerobic activities may provide beneficial cardiovascular effects, improving performance in sports that place a high demand on aerobic energy systems, such as roller hockey, volleyball, football or basketball. Long-term athlete development has been a line of research proposed by a variety of national governing bodies to offer a first step in considering the approach to talent development. The model, which is primarily a physiological perspective, presents an advancement of understanding of developing athletic potential alongside biological growth. It focuses on training to optimize performance longitudinally, and considers sensitive developmental periods known as “windows of opportunity” [20]. Despite advances over the last decade with regard to long-term athlete development, a review of the literature supports the statements of Leite et al. [16] who state that the development of expertise and talent identification in sports remains a major topic of debate. A review of the current state of knowledge reveals an interest in contributions that may be presented for clarifying issues related to the long-term preparation and development of futsal players in Portugal. The main purpose of this study was to identify differences in the variables related to the long-term athlete development, such as the age at which participation in the sports and in futsal started, the number of months of inactivity between the seasons and, further, the amount and type of sports activities in which the players participated during their career as well as the time spent in training at each stage of preparation, in three competitive levels: expert, intermediate and non-experts.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants

- Participants in this study consisted of 317 senior male futsal players from three distinct competitive levels: expert, represented by professional players from teams that, in the last three sports seasons (between 2007 and 2010), ranked in the first three places in the 1st division of the Portuguese futsal championships (n= 60); intermediate, consisting of players from the 2nd and 3rd division teams of the Portuguese futsal championships (n= 106); and non-expert, represented by amateur players in Évora district futsal championships (n = 151). The “ditrict” level is the lowest level of the Portuguese Futsal Ranking System.

2.2. Measures

- The questionnaires, validated by Leite and colleagues and used in some recent studies [16, 21], with athletes in team sports, such as basketball, volleyball, roller hockey and soccer, were adapted to futsal. The first part of the questionnaire was devoted to variables related to the long-term sport development of the player during his career, such as the age at which participation in the sports started (sport starting age), the age at which participation in futsal started (futsal starting age) and the number of months of inactivity between the seasons (inactivity period between seasons). In the second part, the amount and type of sports activities, in which the players participated throughout their long-term sport development (number and type of sports practiced), as well as the time spent in training (average hours practice per week) at each stage of preparation was assessed. In this case, the players' responses were grouped, using the following ordinal scale: 0; 1 (corresponding to 1 to 3 hours); 2 (corresponding to 3 to 6 hours); 3 (corresponding to 6 to 9 hours); 4 (corresponding to 10 or more hours). The ordinal scale was chosen because it is easier for players to recall such information (for example that they trained between 1 and 2 hours) than exactly how many minutes they trained at a certain stage in their long-term athlete development [16, 21]. The proposal presented by Leite et al. [16, 21] was used, for categorization of sports activities: the main sport (in this case, futsal); team sports (collective with opposition), individual sports and combat sports. A fifth category, representing a combination of several types of the above-mentioned sports, was considered for statistical treatment purposes.

2.3. Procedures

- The protocol for data collection consisted of the following phases: (1) the Portuguese futsal team coach provided the contacts (e-mail addresses) of the coaches of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd division teams of the Portuguese futsal championship; (2) the coordinator of the Soccer Association of Évora provided the contacts of coaches of the teams participating in the Évora district futsal championship; (3) the coaches were contacted and the objectives of the study were explained; (4) 20 questionnaire samples were sent to each participating coach, accompanied by an explanatory text, requesting that answers be obtained as soon as possible; (5) the questionnaires were given to the players by their coaches, with a brief explanation as to how they should be filled; (6) two weeks after the questionnaires were sent, the coaches were contacted again (by telephone) to arrange collection of the responses; (7) the responses to the survey were collected directly from the coaches at the end of training sessions.

2.4. Analysis

- The collected responses were recorded in a computer spreadsheet, for descriptive analysis of the data. Long-term athlete development and sports preparation was subdivided, as suggested by Leite et al. [16] and Leite and Sampaio [21], into four stages: initiation (6 to 10 years of age), orientation (11 to 14 years), specialization (15 to 18 years) and adult development stage (19 years and older), they make an adaptation of Côté’s DMSP model [9-11] considering one more stage. Statistical inference consisted of direct comparison between all groups, using the Kruskal-Wallis test and between pairs of groups, through inferential analysis, using the Mann-Whitney test for nonparametric data. Statistical differences were tested using a significance level of 5%. Bonferroni adjustments were applied to correct for multiple tests [8]. All data were analyzed with version 16.0, SPSS statistical package for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

2.5. Reliability of Retrospective Information

- Since the questionnaire relies on the retrospective memory of the players, and given the complexity and depth of the gathered information, the consistency and temporal stability of retrospective information was assessed, using a methodology similar to that used by other researchers [16, 18, 21]. In this study 39 players (12% of the sample) were asked to complete the same questionnaire again, six months after completing it for the first time (re-test questioning). Analysis of temporal stability of responses, through calculating the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the obtained responses, at the two stages of data collection shows significant correlations (p <0.01) for all considered variables. The obtained correlation coefficients for the long-term development variables, sport starting age and futsal starting age were r= 0.936 and r= 0.931, respectively. For the development stages, the correlation coefficients in all four stages (initiation, orientation, specialization and adult) varied between 0.801 and 1 for the number of sports practiced; between 0.711 and 0.926 for the type of sports practiced; between 0.851 and 0.987 for the average hours practice per week and between 0.856 and 0.998 for presence in training.The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Évora.

3. Results and Discussion

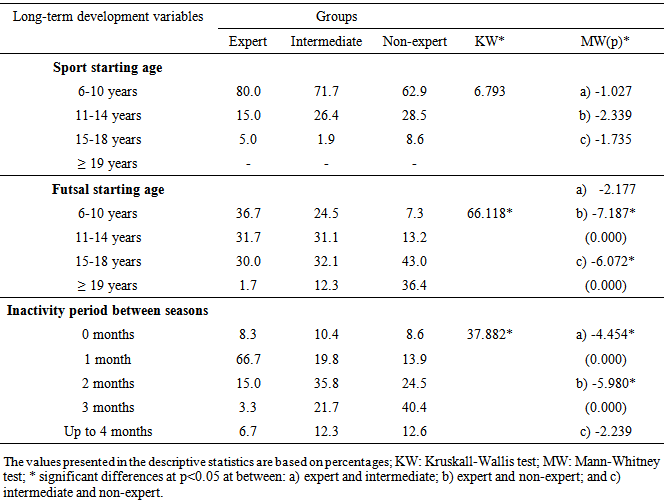

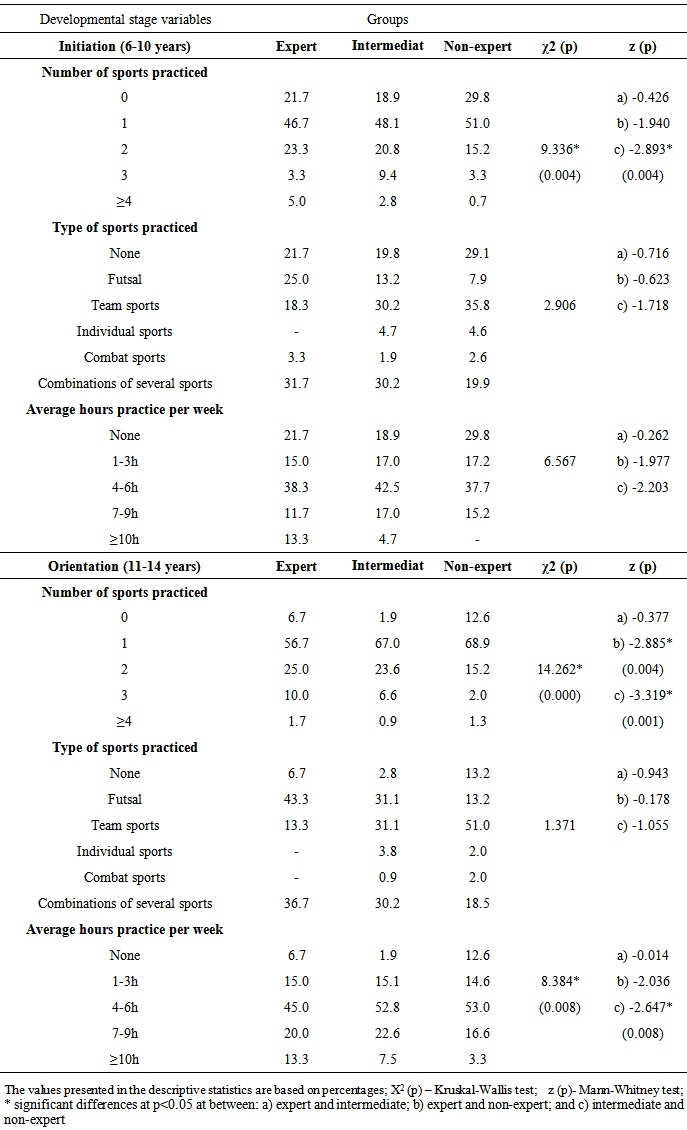

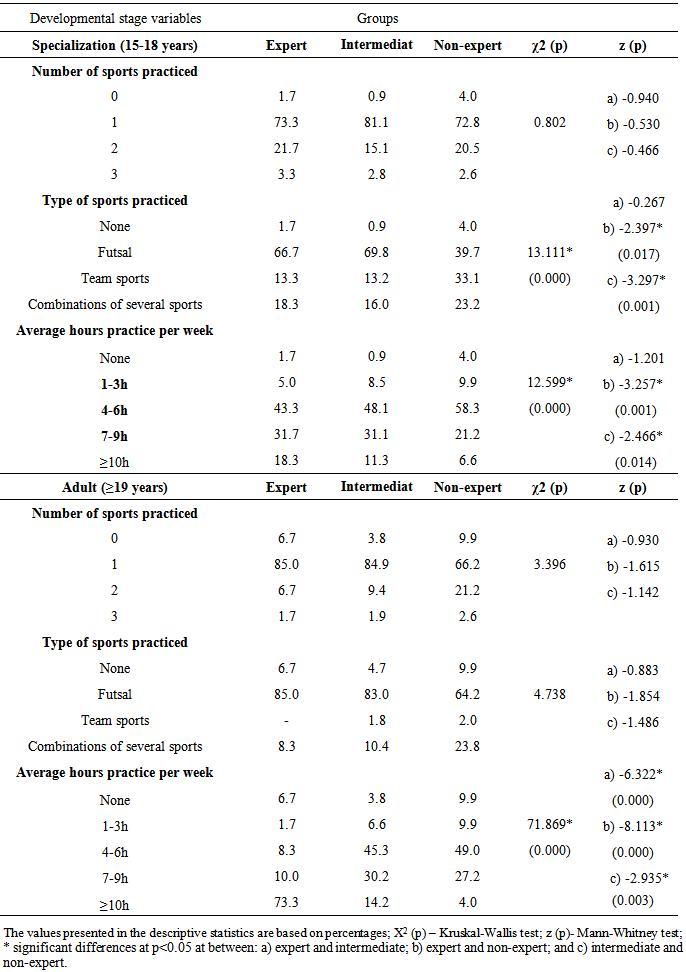

- Table 1 presents the results of descriptive (values expressed as a percentage of the total in each group) and inferential statistics for the long-term variables studied.Tables 2 and 3 summarize the results of descriptive (values expressed as a percentage of the total in each group) and inferential statistics for the variables related to the stages of sporting development: the number and type of sports practiced (specific and non-specific) and number of hours of training involved (average hours practice per week).

|

|

|

3.1. Long-term Development Variables

- Concerning the sport starting age (Table 1), though there was a tendency for starting the sport very early in the groups corresponding to higher competitive level, there were no significant differences between the different groups of players; at any level of competition, more than 90% of the players began participating in sports before 14 years of age.The main differences between groups with different competitive levels were in two main areas: one related to the history of sports practice, which includes futsal starting age (Table 1), the other resulting from the competitive level of practice, with emphasis on the inactivity period between seasons (Table 1) and the time spent in training activities (Tables 2 and 3).The futsal starting age (Table 1) showed statistically significant differences (p< 0.001) between non-expert group and the other groups and there was a trend towards an earlier start in the case of the players at the higher competitive level. While more than 68% of expert players and more than 55% of the intermediate players started playing futsal before 14 years of age, about 80% of non-expert players began playing after 15 years of age. It should be noted that futsal is a relatively new sport, compared to football. There has been a lower development of this sport in Évora (non-experts group), compared to other districts of the Portugal, characterized by championships with a reduced number of teams. This reflects, on the one hand, demographic and structural issues in the country, and on the other, issues related to the image, media attention and expectations that have been created with regard to football and ensuring a professional future. At present, for example, a player may be registered in different clubs in more than one sport (for example football and basketball), as long as it is not futsal and football (because they belong to the same federation and there cannot be two processes from the same player). It is important to allow the players to practice several sports simultaneously, especially at the early stages of development, thus allowing for expertise to occur in the appropriate phases (15 to 18 years old) and not too early. These results at the non-experts level present a well known situation in this region: the players start playing football and go through their whole long-term development in this sports activity. In transition to adult development stage, and since there is no process to facilitate adaptation (neither at the competitive level, nor at the human or emotional levels), players with fewer resources (technical, tactical, physical, psychological or other) are passed over, and futsal provides an opportunity for them to continue physical activity, in a team sport that is very similar to the sports activity that was their first choice, the football. A factor that could contribute towards correcting this situation is for the players to be able to participate in these two sports, football and futsal, simultaneously, throughout their sports development. In this case, the players would have all the necessary tools available when they have to decide their specialization. It is natural that at this point, the futsal level in Évora district is well below that of this sport in other districts of the country. It would be interesting to see if this gap also exists at the level of female competitions, since there is no Women's Football Championship in the region, and the players go through the period of development in futsal.Statistical analyses revealed significant differences in inactivity period between seasons (Table 1) between the expert group and the other groups (p< 0.001), with a tendency to increase in the groups at the lower competitive level; while 75% of expert players have a period of inactivity of less than one month between seasons, about 70% of the players of the intermediate players and about 77.5% of the non-expert group have two or more months of inactivity between seasons. In the case of the non-expert players this fact is easily justified, given that the Évora futsal championship has a small number of teams (8 or 9), with the competitive period reduced to 7-8 months. For the intermediate group the competition period does not exceed 8-9 months, except for the teams participating in the final stages of the championship. In the case of the expert group whose competition lasts for 10-11 months, participation in trainings and competitions of national futsal team completely fills the schedule, leading to the succession of seasons, almost without any interruptions. These results seem to indicate that the inactivity of the non-expert is related with the competition rules and probably not explained from the lower level of the players, so, it should be a topic of discussion and interest in future research.

3.2. Development Stages

- The statistical analyses revealed significant differences between groups in number of sports practiced (Tables 2 and 3) only in the early stages of development (in the initiation stage: z=-2.893, p= 0.004 between the intermediate and the non-expert group; in the orientation stage: z= -2.885, p= 0.004 between the expert and the non-expert group, and z= -3.319, p=0.001 between the intermediate and the non-expert group), which confirms the results of Ward et al. [14], who evaluated the development of high performance football players. As the players go through the stages of sports development, there is a tendency to reduce the number of sports practiced. However, at the adult stage (19 years and beyond), there is a reversal of this trend, in non-experts group. At this stage, 66% of players in the non-experts group only play futsal, while in the other groups (experts and intermediates) this number reaches 85%. The other sport that the non-expert players practice is always football, which reinforces the idea expressed above, that a large percentage of non-expert players who reach the futsal do so in the later stages of development, many of them as adults and as a result of dissatisfaction with or lack of opportunity in football. The reasons why non-expert athletes play other sports in a late phase of their sporting careers can suggest the need to be engaged with sport when athletes do not have success in main sport, topic potential for future research.With regard to the type of sports practiced (Tables 2 and 3) there are only significant differences between the non-experts group and the other groups (z= -2.397, p=0.017 between the expert and the non-expert group, and z= -3.297, p= 0.001 between the intermediate and the non-expert group), at the specialization stage (15 to 18 years old). There is, in all groups, a progressive specialization in futsal, with this sports activity becoming increasingly more important along the stages of development. It is also clear that the groups with the highest competitive level demonstrate the earliest interest in futsal, which reinforces the ideas presented regarding the number of sports practiced. For example, in the orientation stage (11 to 14 years old), while 43.3% of the expert players and 31.1% of intermediate players already practice futsal, only 13.2% of the non-experts players practice this sport. This difference is even more pronounced at the specialization stage (15 to 18 years old), with values of 66.7%, 69.8% and 39.7% respectively, and at the adult stage (19 years and beyond), with values of 85.0%, 83.0% and 64.2%, respectively. It is also important to mention the reduced number of individual sports in general and of combat sports in particular (less than 5%) in the long-term development of futsal players, regardless of the level or the stage of development. While their potential is recognized in terms of motor skills or psychological capacities, these types of sports, from the outset, allow little transfer for technical and tactical specifics of futsal.These results could indicate that early specialization is required in futsal, which would be in line with the theory of deliberate practice that emphasizes early specialization [7], but would contradict what happens in other sport activities, as supported by the work of Baker et al. [13] and Leite et al. [16], reinforcing the idea that this is an open issue [16]. Probably, the participants of this study started to play futsal because it is the sport with higher social and cultural impact in Portugal and not because this sport requires an early specialization. Leite et al. [16] defend early diversification instead of early specialization, based on their results regarding the complexity of the processes underlying acquisition of skills in the sport, and the diversity of ways to achieve specialization, depending on the sport activity involved. The relevance of the present study is especially warranted because there have been no published studies about the long-term development of futsal players. The fact that it is a relatively recent sport activity and relevant only in countries in South America such as Brazil, in Southern Europe, such as Spain, Italy and Portugal and in some countries in Eastern Europe, justifies the little reference to this sport activity in research studies in Anglo-Saxon or American literature, where more frequent references to football or other types of indoor sports with greater popularity, such as basketball, volleyball or handball, can be found.As stated by Baker et al. [13] and Leite et al. [16], it is important to provide an objective determination of the accumulated contribution of different sports activities, practiced outside the area of specialization, to the performance level of adult players. The question of transfer among sports activities is an area of great potential for research in the coming years. Williams and Ford [20] particularly emphasize the need to evaluate aspects such as concentration, dedication and ability to motivate for intense training, which influence the development of young athletes at different stages throughout their career.The variable average hours practice per week (Tables 2 and 3) shows a differentiated behavior along the different stages of development. While in the initiation stage there are no significant differences between the groups, there are significant differences between the experts group and the non-experts group (z= -2.647, p= 0.008) in the orientation stage. In the specialization stage there are significant differences between the non-experts group and the other groups (z= -3.257, p= 0.001 between the experts group and the non-experts group, and z= -2.466, p= 0.014 between the intermediates group and the non-experts group). In the period after specialization (adult stage, 19 years and beyond) the differences become significant among all competitive levels (z= -6.322, p< 0.001 between the experts group and the intermediates group, z= -8.113, p< 0.001 between the experts group and the non-experts group, and z= -2.935, p= 0.003 between the intermediates group and the non-experts group). At this last stage of development, more than 80% of the expert players spend 7 or more hours on training, while in the corresponding intermediate players this figure is about 40%, decreasing to about 30% in non-expert players.One must keep in mind that rather distinct groups are being analyzed in this case study: while the expert group is composed of professional players, who regularly train 1-2 times per day (73.3% of the players over 18 years train 10 hours or more per week), the players in the non-experts group are amateur and regularly train twice a week (about 69% of the players train 6 hours or less per week). The intermediates group presents an intermediate value for this assessment variable, reflecting the common pattern of the tendency for an increase in the number of hours of weekly practice with the increase in the competitive level of the players. These results confirm the indications of Baker et al. [2], regarding the clear commitment of experts to training in the later stages of sports development.

3.3. Study Limitations

- The main limitation of this study was the use of data collected based on retrospective memory of the players. Despite safeguarding consistency of the answers, there are always some reservations regarding this type of information, which is a viable alternative, given that the current developments in creation and management of electronic databases, open the doors for future longitudinal studies based on official records of the clubs or scientific observation of the sports activity which can confirm the results published here.These findings and the diversity of approaches evident in literature review, regarding long-term athlete development of experts justify the current interest in carrying out further research in this area, in particular, using a sample that would make it possible to compare the players of international championships, to clarify whether futsal presents specific characteristics with regard to a need for early specialization and deliberate practice of the players who achieve expertise. Inclusion of football players in a future sample could also be helpful in order to try to understand if the question of deliberate practice versus diversified practice, the first demonstrated in this study for the long-term development of futsal players, the second demonstrated, for example, by Leite et al. [16] for basketball players, are supported scientifically at the level of motor control, since in the case of the first it is the lower limbs that are the active technical limbs, while in the latter, it is the upper limbs, with differentiated connections to the brain. It would also be interesting to adapt the questionnaire in such a way as to try to clarify other issues that remain open in the literature, such as the importance of parental support and coaches on the players’ dedication and commitment to training or the practice of a wide range of non-specific sports with a strong component of dynamics of decision making during key periods of development, which might be crucial to achieving expertise in futsal. Still, as other opportunities for new studies in this area, it might be of interest to use questionnaires to gather information from the coaches, and to find out their opinion regarding the specific characteristics that make it possible for players to be classified as experts in futsal.

4. Conclusions

- This study has contributed towards a better understanding of the long-term development of expert futsal players in Portugal and to identify the underlying mechanisms, using the expert players as a reference. The main differences between players of the three competitive levels considered (expert, intermediate and non-expert) can be grouped in two main areas: one related to the history of sports practice, the other resulting from the competitive level of practice. Given the results of this study, it can be stated that the pattern that characterizes the long-term athlete development of experts in futsal in Portugal has the structure similar to the Côté model (DMSP), with the following characteristics: they are players who begin practicing various sports, including futsal, in the early stages of development, (stage of sampling or diversify practice); have a tendency for progressive specialization; and, after the age of 15 to 18 years, the investment to achieve a high level of performance in futsal is based in a short period of inactivity between seasons (less than one month) and a growing commitment to the modality in terms of hours of training and persistence in training. The persistence for training is a variable that can be of interest for future research, where it is fundamental to evaluate the influence of family members and coaches, as well as the individual motivation for practice.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML