-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Plant Research

p-ISSN: 2163-2596 e-ISSN: 2163-260X

2014; 4(4A): 1-7

doi:10.5923/s.plant.201401.01

The Practice of Local Wisdom of Tobelo Dalam (Togutil) Tribal Community in Forest Conservation in Halmahera, Indonesia

M. Nasir Tamalene1, Mimien Henie Irawati Al Muhdhar2, Endang Suarsini2, Fatkhur Rochman2

1Biology Education, Khairun University Jalan Bandara Babullah, Ternate, Indonesia

2Biology Education, State University of Malang Jalan Semarang 2, Malang, East Java, Indonesia

Correspondence to: M. Nasir Tamalene, Biology Education, Khairun University Jalan Bandara Babullah, Ternate, Indonesia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The TobeloDalam (Togutil)tribal community has inherited local wisdom in managing the forest resources from their ancestors. The loss of these local wisdom values have led to the ecological crisis which creates an imbalance situation in the ecosystem. The community is expected to realize that the ecological crisis can be saved back through local wisdom. To save the ecological crisis, the society ethics of the native tribes needs to be gained back. A participant observation and open interviews were done to investigate this issue. In the participant observation, the researchers were involved in the informants’ daily activities. Open interviews were also conducted at this stage. There were 21 informants; 12 persons come from the area of river Tayawi and 9 persons come from river Suwang. The results of the research revealed the fact that the local wisdom possessed by the TobeloDalam (Togutil) tribal community has been manifested in their concept of philosophy of life, the knowledge of the physical environment, and the conservation of the forests. Local wisdom in the management of the forest resources can still survive despite the influence from outside. The local wisdom is eternal since the people maintain their philosophy of life, HidupBasudara (live in harmony) which contains a belief that people and nature need to live side by side. The practice of local wisdom-based conservation that takes the form of the sacred forest of Gosimo, Matakau, Pohon Kelahiran (Tree of Birth) and Pohon Kematian (Tree of Death) is a part of local knowledge that continues to be taught to the next generation. It becomes an invaluable ancestral heritage in forest conservation.

Keywords: Local Wisdom, Tobelo Dalam (Togutil), Forest Conservation

Cite this paper: M. Nasir Tamalene, Mimien Henie Irawati Al Muhdhar, Endang Suarsini, Fatkhur Rochman, The Practice of Local Wisdom of Tobelo Dalam (Togutil) Tribal Community in Forest Conservation in Halmahera, Indonesia, International Journal of Plant Research, Vol. 4 No. 4A, 2014, pp. 1-7. doi: 10.5923/s.plant.201401.01.

1. Introduction

- Indonesia has resources and biodiversity that are very important and strategic for the survival of the people. It is not solely because of its position as one of the world's richest countries in biodiversity (mega-biodiversity), but because of its close linkages with the richness of local culture diversity possessed by this nation (mega-cultural diversity). The founders of Republic of Indonesia have already realized that Indonesia is an archipelago country that has pluralist political system and laws and diverse socio-cultural condition. The "Bhinneka Tunggal Ika" philosophically indicates respect for that diversity [1]. It is further said that from the diversity of the local systems, there is some traditional wisdom that is respected and practiced by indigenous communities in Indonesia. They are: 1) the dependence of humans on nature that requires a positive harmony, in which they become a part of the nature itself, which should be kept and preserved in balance; 2) mastery over the specific indigenous rights as exclusive and/or shared ownership communities (communal property resources) or collectively known as indigenous territory (in Maluku, known as the petuanan, in large parts of Sumatra are known for ulayat dan tanahmarga) that binds all citizens to maintain and manage it for justice and shared prosperity as well as to help avoid the exploitation by outside parties.Many examples of cases showed that the persistence of communal or collective ownership system can prevent excessive exploitation of the local environment; 3) system knowledge and structure of cultural settings ('Government') which providesability to solve the problems they face in the utilization of forest resources; 4) Allocation System and customary law enforcement resources to secure the resources from excessive use, either by the community itself or by the outside community; 5) Mechanism of equitable distribution of the results of the "harvest" of natural resource belonging together that could dampen social jealousy in the midst of the community. Local wisdom is a part of the cultural local knowledge that is formed through a process of learning by way of observation, testing, practice and its spread in people [2]. Local knowledge is stored in the minds of locals, either individually or in groups. The meaning of local knowledge is much broader than the term "traditional wisdom" a memorable static or less adapted to changes. Everything is 'traditional' is not always able to resolve the question of natural resources and the environment, or in tune with the aspects of preservation. Local knowledge is constantly evolving. It may be a result of a merger between the experiences in the community with the knowledge of an outsider [3]. Local traditional wisdom in accordance with its origin is one of the cultural heritages that exists in the society and is orally administered by community groups concerned. Local wisdom includes knowledge, whether it is obtained from the previous generation as well as from a wide range of experience in the present. Local wisdom could be interpreted as a set of knowledge, values and norms of a particular form of adaptation and life experience of a social group who lives in a certain location [4]. The environment and the life experiences have taught humans to develop patterns of thinking and patterns of a specific action; because that is the only way they can make peace with the environment, with themselves, with each other and with members of other groups.There is one of the indigenous communities living in remote forests of Halmahera Island, namely the Tobelo Dalam (Togutil). Remote indigenous community of Togutil is known to have had knowledge of the utilization and preservation of natural resources, biological diversity, including knowledge of the utilization of genetic resources in agriculture. However, knowledge systems, owned by community Togutil have not been well documented. The documentation of the Togutil knowledge system will be very meaningful for adding information about the diversity of genetic resources that are utilized by the community of Togutil that have the potential to be developed further in the program of agricultural cultivation as well as efforts to prevent the occurrence of erosion [5]. Togutil tribe lives are very dependent on hunts, sago, and simple agricultural systems [6]. The loss of forest resources means the destruction of most of the tribal life of the Togutil indigenous community because it was claimed as their habitat since long time ago.Togutil tribal community’s dependence on nature makes them have a nomadic life pattern. They will move to a new area if they have run out of fruit and animals to eat in that place. They were known as the owner of the forest in Halmahera because it was them who first explored it. Togutil tribal community live from hunting and gathering forest products. They eat sago (Metroxylon sagu Rottb) as the source of carbohydrate. At this time, most of them are farmers (Togutil non-nomaden residents) and some still depend on forest products, although they have been familiar with the farming system (the Togutil temporary residents). In addition, they hunt for food, look for rubber from damar tree (Agathis dammara (Lamb.) Rich.), and collect Maleo eggs (Macrocephalon maleo) to be sold or exchanged with the residents in the village on the market days. Togutil people believe in the spirit of the ancestors that occupy the entire natural environment [7, 8]. Togutil community believes the existence of the supreme power and authority known as Jou Ma Dutu, the owner of the universe or is usually called aso gikiri-moi which means the soul or life. Togutil people, however, never do the rites of worship. They never mention the term or name specific to the original religion system. The original beliefs of the Togutil are centered on respect and worship to the ancestors which are depicted in various spirits occupying the whole environment in the form of a natural object (nature) as well as the objects of copyright works of man (culture) that have power to influence success and failure.Togutil live in the remote areas of Halmahera. They are nomads and semi nomads grouped in a particular community. The other Togutil can be found in some areas such as Tobelo, Dodaga, Kao (near Gunung Sembilan), Wasilei (Dodaga Village, Tukur-Tukur, Tutuling Jaya, Toboino (Totodoku), and at Maba and Buli. Every primitive tribe has claimed their own territory. The area is generally bounded by hills, rivers, or certain trees. The area is a region where they search for food through hunting and cultivating. There will be conflicts between communities if they have passed other tribe’s territory. In general, people in North Maluku recognize Togutil as a primitive and there is only one group of the tribes inhabits the forests of Halmahera. This tribe lives in their respective communities such as Togutil Tobelo, Togutil Kao, Togutil Dodaga, Togutil Wasilei, Togutil Suwang, Togutil Maba and Togutil Tayawi. This means that by organizing small groups, they have tried to maintain their livings.From the perspective of culture, the concept of biodiversity cannot be separated from the human factors which have a responsibility towards the sustainability of the diversity that exists on Earth. UNESCO and UNEP in the World Summit on sustainable development held in Johannesburg in 2002 stated that sustainable development covers both cultural diversity and biodiversity. It is to protect biodiversity and simultaneously appreciate and recognize the rights and role of the local people as the main agents that maintain and shape the biodiversity. UNESCO declared that we will not be able to understand and conserve our natural environment if we do not understand the culture of the human beings who make up the nature. Cultural diversity is a reflection of the biodiversity. The statement means that each culture builds on knowledge, practices, as well as other cultural representations in utilizing and maintaining environmental sustainability and natural resources [10]. Those things are reflected in the everyday life and local traditions that is local wisdom.The local wisdom of Tobelo Dalam (Togutil) tribal community is unique regarding the management of forest resources on the island of Halmahera. In many cases, local wisdom in managing forest resources has become extinct along with the decimation of biodiversity, but early in the 21st century, the discourse on local wisdom has been a focus of government as an important part in development programs in the future. The existence of ecological crises lately has led to a new awareness that ecological crisis can be saved back through local wisdom in Tobelo Dalam tribal community (Togutil). To save the ecological crisis, it is necessary to review the native ethics, local wisdom and wealth, and to solve the ecological crisis which is mainly caused by errors of perspective and behavior of modern society.

2. Materials and Methods

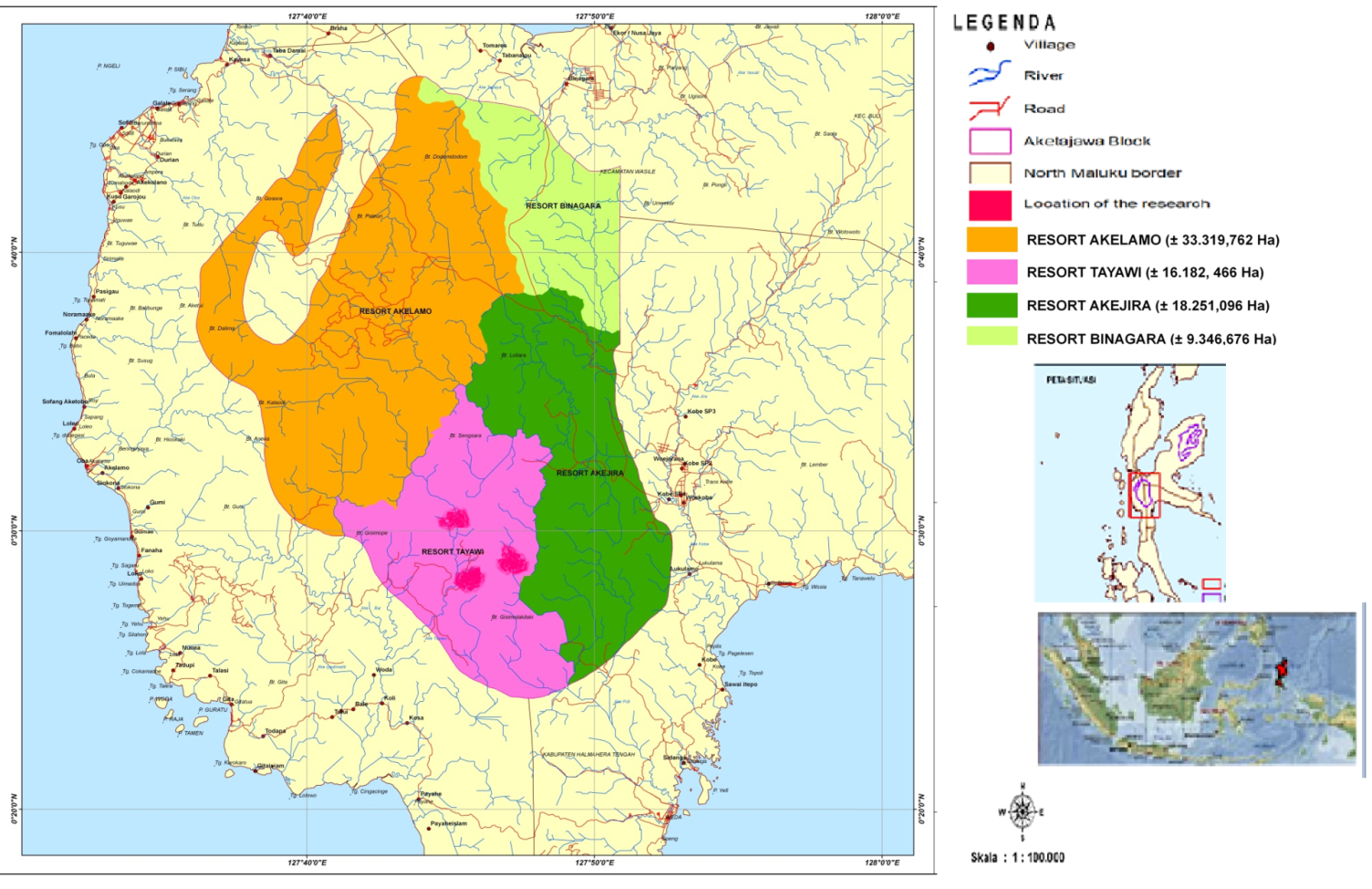

- The study was carried out in May to August 2014. The method of this research is in-depth observations and interviews. The interviews were used to obtain data about the local wisdom of Tobelo Dalam (Togutil) tribal community in the practice of forest conservation in Halmahera. The observation done was a participant observation meaning that the researchers were involved in the informants’ daily activities. Open interviews were also conducted at this stage. Purposive sampling technique was employed to choose the informants who are regarded as experts in local wisdom of Togutil. Informants cannot speak Bahasa Indonesia. Thus, they were assisted by a translator. The study was conducted in regions along the Tayawi in Koli and river Suwang in Gita, district Oba, Tidore Islands (Figure 1). There were 21 persons involved in this study, 12 people come from the region of the river Tayawi and 9 people come from the region of the river Suwang.

| Figure 1. Location of the Research (Halmahera Island) |

3. Results and Discussion

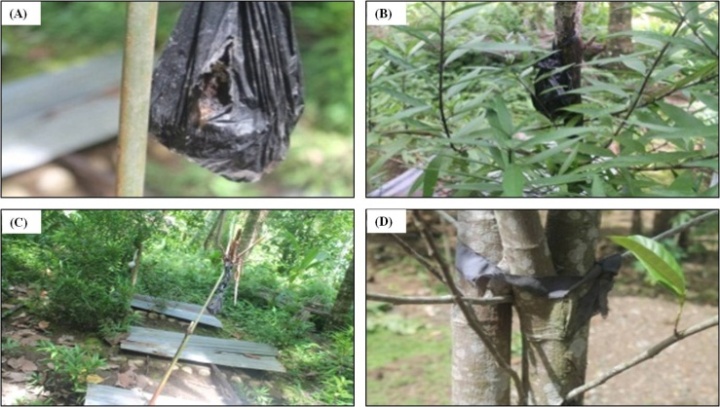

- Local wisdom can still be found in the community of Tobelo Dalam (Togutil). It includes the view of life; knowledge of the physical environment and conservation in the management of forest resources; Here are some form of local wisdom that has been practiced by the tribal community of Tobelo Dalam (Togutil):Kermat Gosimo ForestThe Sacred Forest of Gosimo is found in the community of Tobelo Dalam (Togutil). Gosimo is derived from the Tidorelanguage which means older people (ancestors) while in Ternate called Himo-himo. There are two types of Gosimo forests, namely Gosimo male forest and Gosimo female forest. Both types of the forest are bounded by river Tayawi and the area is unknown because it is pamali (taboo) to be measured. Each person is not given permission to enter the forest. They are not allowed to cut and take timber or forest products from the forest. In principle, people can only enter the hallowed forest when there are specific ceremonial purposes, such as: community safety when there is a ceremony for the sick person. The ceremony is not performed by a tribal community Tobelo Dalam (Togutil) but done by people outside of this community, that is, certain people who have supernatural powers derived from the village of Gita. This ceremony is done to appease the ancestor (the owner of the forest). Spells will be read and some gifts will be delivered to the owner of the sacred Gosimo forest. Tribal Community Tobelo Dalam (Togutil) has the view that the forest is part of their belief structure. Prohibition to enter the Gosimo forest area has already become a tradition in the community of Tobelo Dalam (Togutil). There is an early warning informed orally to their children, the communities surrounding the forest, and guests from various cities in Indonesia, even abroad. Everyone is forbidden to cut and take timber or other forest potential because it will pose a danger to one's own as well as his family. The forests are sacred to the people in Tobelo Dalam (Togutil); therefore, they need to protect them.Although the local wisdom is not familiar with the term conservation, local community have been practicing plants and animals conservation. They determine a community forest areas or sites that are sacred to be protected together. Such local wisdom has been proven to save a region along with their contents with various forms of restrictions for those who break them [11,12]. Local wisdom will guarantee the success because it contains norms and social values that show how they should establish a balance between resource carrying capacity of the natural environment with the lifestyle and needs of mankind as an illustration from a social point of view about poverty. By digging and developing local wisdom, poverty can be prevented because the natural resources have been maintained for the next generation. Results of other studies have proven that traditional religions and local cultural practices have contributed to forest conservation [13]. Traditional belief against something taboo helps enforce the rules for the preservation of the environment, for any person has to refrain from the use of resources in vain, mainly related to the Holy places. In particular, the important role of these practices in the conservation of biodiversity is essential for the protection of forests and other natural resources. The practice of local wisdom traditions strengthens the emotional relationship between Tobelo Dalam tribal communities (Togutil) and their environment.The combination of the physical and psychological aspects form an emotional attachment to the environment so as to establish the attitude of caring for the environment. Tribal community Tobelo Dalam (Togutil) has long been settled and cultivating along the river Tayawi and river Suwang, although some families still live as semi nomadic. This community believes that living close to the water and forests will provide benefits to their lives and their families. Indigenous communities of Tobelo Dalam (Togutil) have a philosophy of life, namely; Basudara. This principle prioritizes life that is based on the principle of unity and togetherness among fellow community as well as with nature. For instance, hunting results or the results of the forest will be shared collectively in communities that live side by side. They view the forests as a friend and a home for them so the forests need to be protected.MatakauMatakau is a concept of forests or land protection for social, economic, and ecological community conducted by the tribe of Tobelo Dalam (Togutil). This concept is a part of the traditional knowledge that is constantly kept up to now. Matakau in practice is that if a forest area or land owned by the community of Tobelo Dalam (Togutil) is taken secretly without the knowledge of the owner of the land, it will be exposed to Matakau. Matakau is placed next to or inside the forest/land that has the potential for economic (Figure 2). Someone affected by Matakau will not be able to walk and stand at the location where the person is taking the resources from the forest or area belonging to the tribal community of Tobelo Dalam (Togutil). Someone affected by Matakau can be cured if they are discovered by the owner of the land. The extreme impact of the Matakau on people is causing pain and even death. The forest or land protection established by the Tobelo Dalam tribal community (Togutil) is actually the real form of local wisdom-based forest conservation practice which combines the main principle of traditional knowledge that is the relationship with nature and the relationship with other human beings.

| Figure 2. Matakau to protect the plants (A) Matakau Plant Conservation house (B) |

| Figure 3. Trees of birth Lansium domesticum (A) Sida rhombifolia (B), Trees of death Bambusa glaucescens (C) Artocarpus heterophyllus (D) |

4. Conclusions

- The community of Tobelo Dalam (Togutil) has local wisdom that is realized through the concept of philosophy of life, the knowledge of the physical environment, and the conservation of forests. Local wisdom in the management of forest resources can still survive despite the influence from outside the culture, due to some constituents which come from tribal community itself, namely the relationship between the factors of the local community with nature that is transmitted through the philosophy of hid up Basudara (live in harmony). This philosophy is believed to be a guideline for living with nature. The practice of local wisdom based conservation that takes the form of the sacred forest of Gosimo, Matakau, tree of birth and tree of death is local knowledge that continues to be shared with the next generation because the local wisdom is an ancestral heritage which has conservative meaning to preserve the forest.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML