-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Optics and Applications

p-ISSN: 2168-5053 e-ISSN: 2168-5061

2014; 4(4A): 25-52

doi:10.5923/s.optics.201401.04

Optical Characterization of “Rondine®” PV Solar Concentrators

Antonio Parretta1, 2, Edgar Bonfiglioli1, Letizia Zampierolo1, Mariangela Butturi3, Andrea Antonini4

1Physics Department, University of Ferrara, Via Saragat, Ferrara (FE), Italy

2ENEA Centro Ricerche “E. Clementel”, Via Martiri di Monte Sole, Bologna (BO), Italy

3CPower Srl, Via Capitello di Sopra, Marano Vicentino (VI), Italy

4Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia (IIT), Nanostructures Department, via Morego, Genova (GE), Italy

Correspondence to: Antonio Parretta, Physics Department, University of Ferrara, Via Saragat, Ferrara (FE), Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The collection properties of nonimaging “Rondine® ” PV solar concentrators are investigated by indoor measurements of the angle-resolved optical efficiency. We illustrate two different methods to draw the optical efficiency curve. The first one, briefly called as “direct method”, is performed by producing a uniform and collimated beam of known flux impinging on the input aperture of the concentrator at different incidence angles, and by measuring the flux collected at the exit aperture. The second method, called “inverse method”, is based on a reverse illumination procedure, whereby a lambertian diffused light is produced at the exit aperture of the concentrator, and the radiance of the beam transmitted backwards from the input aperture is measured at different directions in space. The obtained results are similar for the two methods, but the “inverse method” is largely to be preferred for the simplicity of the experimental apparatus and the extreme quickness of execution.

Keywords: Solar Concentrator, Nonimaging Optics, Optical Characterization, Modelling and Analysis

Cite this paper: Antonio Parretta, Edgar Bonfiglioli, Letizia Zampierolo, Mariangela Butturi, Andrea Antonini, Optical Characterization of “Rondine®” PV Solar Concentrators, International Journal of Optics and Applications, Vol. 4 No. 4A, 2014, pp. 25-52. doi: 10.5923/s.optics.201401.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

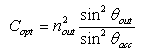

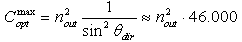

- The development and assessment of concentration photovoltaics (CPV) technology is facilitated by the use of optical characterization techniques that qualify the properties of the concentrator in terms of overall optical efficiency; this figure of merit is measured in conditions of perfect alignment with respect to the solar disk, as well as in function of the extent of misalignment [1-5]. The concentration system is usually assemblies of many optical and mechanical parts, so it is useful to proceed to the characterization of the individual components of the system to help their performance analysis. This process can be carried out both experimentally, in laboratory, or virtually, by using optical software. In this last case, the single components are assembled in a CAD model and tested in optical simulation software to extract the performance expected for the system as a whole. In this paper we will discuss two methods of characterization of concentration units, one of them having proved to be extremely powerful to measure the efficiency losses due to misalignment of the concentrator from the solar disk [6-24]. The characterization methods will be applied to two small concentration units called "Rondine" developed by the company CPower Srl [25-30]. Before explaining the two methods of characterization, it is useful to briefly summarize the basic concepts that underlie the behaviour of a solar concentrator [31-39]. A solar concentrator is an optical device that works mainly on direct solar radiation, and, in its simplest form, can be realized by using lenses or mirrors. In the first case we refer to refractive concentrators, in the latter case to reflective concentrators. In reality, a concentrator can be more complex, designed combining more elements of refractive and reflective nature. In a 3D or point-focus solar concentrator the incident rays are forced to cross increasingly smaller areas and at the same time to increase their angular divergence θ, as established by Liouville's theorem: A · sin2θ = const (valid for an ideal concentrator without optical losses). So, the concentrator increases the incident flux density, starting from about 900 W/m2 (a value typical of clear sky conditions) up to values, which depend on the optical concentration ratio,

:

: | (1) |

is the maximum angular divergence of output rays,

is the maximum angular divergence of output rays,  is the acceptance angle, that is the angle at which the efficiency of the concentrator drops to the 50% of the maximum, and

is the acceptance angle, that is the angle at which the efficiency of the concentrator drops to the 50% of the maximum, and  is the index of refraction of the medium embedding the receiver. When the SC is irradiated by the direct component of the sun, to collect all the direct irradiation it is necessary to have

is the index of refraction of the medium embedding the receiver. When the SC is irradiated by the direct component of the sun, to collect all the direct irradiation it is necessary to have  , where

, where  is the maximum divergence of direct sunlight incident on the Earth's surface, determined by the particular geometry of the Sun-Earth system [40]. The maximum optical concentration ratio is reached when the divergence of rays at output is

is the maximum divergence of direct sunlight incident on the Earth's surface, determined by the particular geometry of the Sun-Earth system [40]. The maximum optical concentration ratio is reached when the divergence of rays at output is  = 90° and

= 90° and  :

: | (2) |

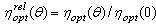

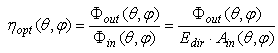

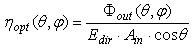

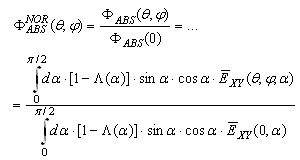

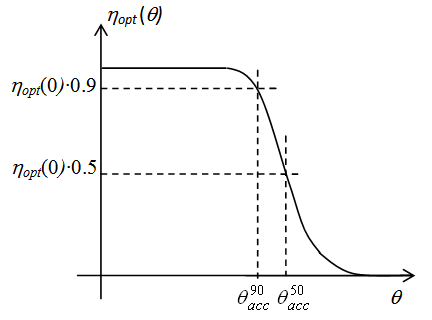

is defined as the ratio of the output to the input flux and significantly depends on the orientation of the concentrator with respect to the solar rays (see fig. 1). Besides the absolute efficiency

is defined as the ratio of the output to the input flux and significantly depends on the orientation of the concentrator with respect to the solar rays (see fig. 1). Besides the absolute efficiency  , it is useful to consider the relative, or normalized, optical efficiency

, it is useful to consider the relative, or normalized, optical efficiency  , which contains only the information of the effect, on the light collection efficiency, of misalignment of concentrator with respect to the solar disk.

, which contains only the information of the effect, on the light collection efficiency, of misalignment of concentrator with respect to the solar disk.2. The “Rondine” PV Concentrator

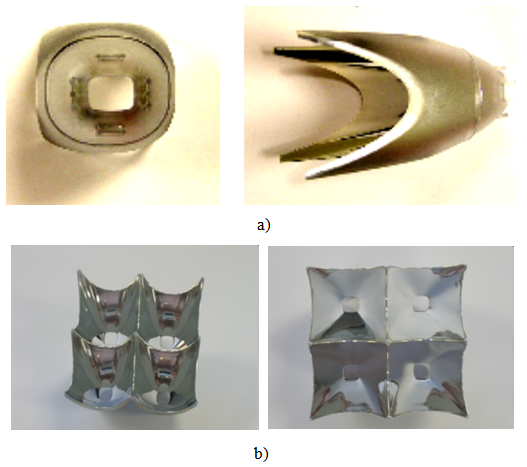

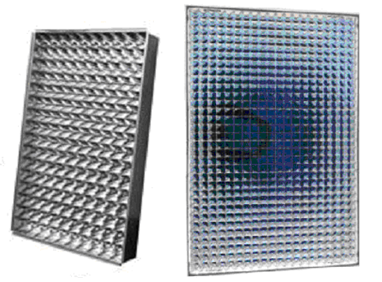

- The “Rondine” PV concentrator is a modular structure composed of original nonimaging optical units of the class of light cones, derived from the compound parabolic concentrator (see Figs. 2-4) [25-30]. The concentrator length has been defined to obtain about only one reflection for the rays entering parallel to the optical axis of the concentrator and striking the surface, to reduce the optical losses due to multiple reflections. The elementary concentrator has a squared input window and lateral apertures; in this way, many elementary units can be closely joined in a dense array, without losses due to the packaging. This approach gives the same angular tolerance like having perfectly flat-mirrored surfaces placed on the cut lateral planes. The absence of a symmetrical rotational axis gives an irradiance distribution on the solar cells without one single hot spot; this illumination profile reduces possible losses in FF due to the distributed series resistance of the devices.

| Figure 4. First installation of a 4kWp tracking Rondine Gen1system, at Ostellato (Ferrara, Italy) |

3. “Direct” Characterization Method

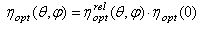

- With “direct” characterization method we briefly intend the “Direct Collimated Method”, DCM, whose detailed theoretical treatment can be found in refs [6, 7]. Here we summarize the basic principles of this method. The DCM consists, in principle, in drawing the optical transmission efficiency curve of the concentrator when it is irradiated by a parallel and uniform beam at different orientations in space, the transmission efficiency being defined as the ratio between output and input flux as function of the polar θ and azimuthal φ angles of incidence of the beam:

| (3a) |

is the area of input aperture projected along direction (θ, φ). If the input aperture is planar and with area Ain , Eq. (3a) simplifies as:

is the area of input aperture projected along direction (θ, φ). If the input aperture is planar and with area Ain , Eq. (3a) simplifies as:  | (3b) |

| Figure 5. Basic scheme of the Direct Collimated Method (DCM) |

| (4) |

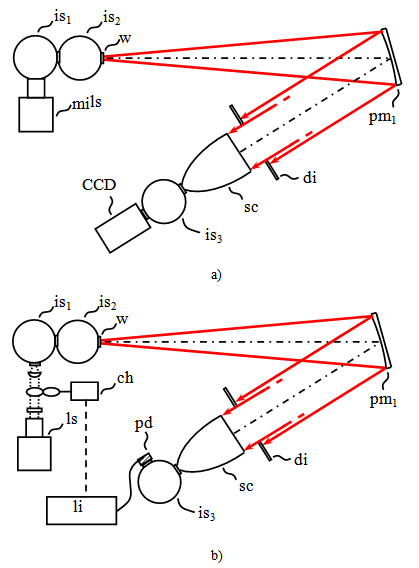

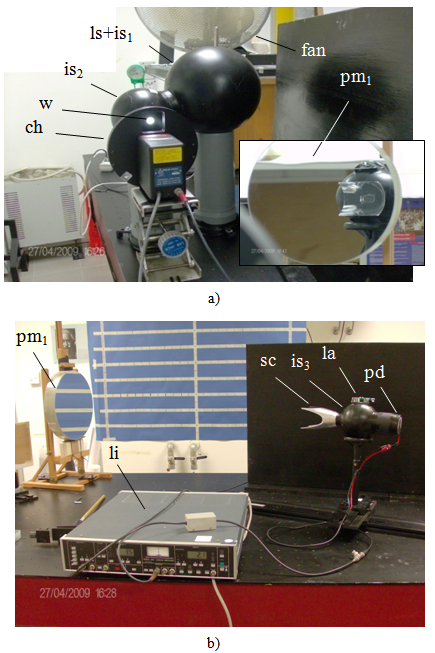

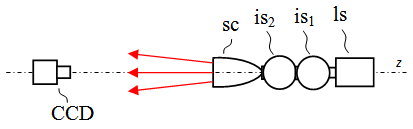

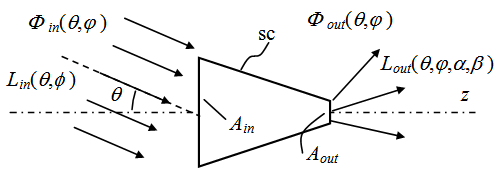

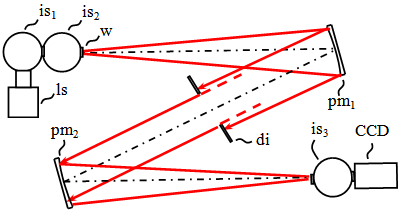

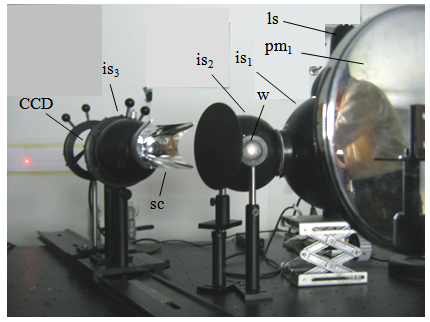

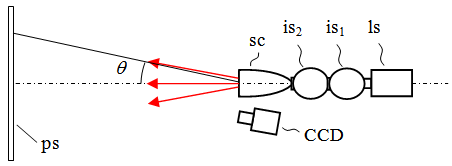

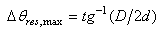

is the efficiency relative to 0° incidence. To draw out the optical efficiency curve experimentally, we have to prepare the ±0.27° divergent beam with a uniform irradiance distribution on the cross section and with an orthogonal section area sufficiently large to include the input aperture area of the concentrator. Then it is necessary to measure the flux Φout (θ, φ) collected at the exit aperture of the concentrator for different orientations of the concentrator respect to the incident beam. The polar incident angle θ is sufficient to define the orientation of the concentrator when it has a cylindrical symmetry, like a standard CPC; for other concentrators, like the “Rondine” in this paper, it is necessary to consider also the azimuthal incident angle φ. We will limit, however, our study with the DCM method only to two azimuthal orientations for the Rondine Gen1, those parallel to the two edges of the input aperture profile, and to one azimuthal orientation for the Rondine Gen2, that parallel to one edge of input aperture profile. To prepare the collimated beam we use a light source (ls) which illuminates two coupled integrating spheres (is1) and (is2) (see the two configurations of Fig. 6 that will be discussed later): the light produced at the output window (w) of (is2) is a diffused light with Lambertian intensity distribution. The use of two integrated spheres instead of one is preferred to have a better integration of light inside the sphere used as source of diffused light. If the window (w) is placed at the focal point of the parabolic mirror (pm1), then the light beam reflected by the mirror is quasi-collimated with a maximum angular divergence fixed by the window dimension and the mirror focal length. To obtain the 0.27° divergence, it is necessary to adjust the ratio between window (w) diameter and mirror focal length to ~1:100, the same ratio between Sun diameter and Sun-Earth distance. The quasi-collimated beam is then selected by diaphragm (di) and directed to the solar concentrator (sc), whose output flux is measured by coupling the exit aperture with a third integrating sphere (is3), and measuring the irradiation level inside the sphere by a suitable radiometric unit. By this way the optical efficiency

is the efficiency relative to 0° incidence. To draw out the optical efficiency curve experimentally, we have to prepare the ±0.27° divergent beam with a uniform irradiance distribution on the cross section and with an orthogonal section area sufficiently large to include the input aperture area of the concentrator. Then it is necessary to measure the flux Φout (θ, φ) collected at the exit aperture of the concentrator for different orientations of the concentrator respect to the incident beam. The polar incident angle θ is sufficient to define the orientation of the concentrator when it has a cylindrical symmetry, like a standard CPC; for other concentrators, like the “Rondine” in this paper, it is necessary to consider also the azimuthal incident angle φ. We will limit, however, our study with the DCM method only to two azimuthal orientations for the Rondine Gen1, those parallel to the two edges of the input aperture profile, and to one azimuthal orientation for the Rondine Gen2, that parallel to one edge of input aperture profile. To prepare the collimated beam we use a light source (ls) which illuminates two coupled integrating spheres (is1) and (is2) (see the two configurations of Fig. 6 that will be discussed later): the light produced at the output window (w) of (is2) is a diffused light with Lambertian intensity distribution. The use of two integrated spheres instead of one is preferred to have a better integration of light inside the sphere used as source of diffused light. If the window (w) is placed at the focal point of the parabolic mirror (pm1), then the light beam reflected by the mirror is quasi-collimated with a maximum angular divergence fixed by the window dimension and the mirror focal length. To obtain the 0.27° divergence, it is necessary to adjust the ratio between window (w) diameter and mirror focal length to ~1:100, the same ratio between Sun diameter and Sun-Earth distance. The quasi-collimated beam is then selected by diaphragm (di) and directed to the solar concentrator (sc), whose output flux is measured by coupling the exit aperture with a third integrating sphere (is3), and measuring the irradiation level inside the sphere by a suitable radiometric unit. By this way the optical efficiency  of the concentrator relative to the on-axis direction (0° incident angle) is obtained.

of the concentrator relative to the on-axis direction (0° incident angle) is obtained. , it is necessary to make a further measurement of

, it is necessary to make a further measurement of  . This is done by removing the concentrator (sc), decoupling it from sphere (is3), and orienting the collimated beam from mirror (pm1) towards a second parabolic mirror (pm2) (see Fig. 7), which will provide to re-focalise the beam inside the same integrating sphere (is3). For this measurement, it is required the knowledge of the spectral reflectance of (pm2).

. This is done by removing the concentrator (sc), decoupling it from sphere (is3), and orienting the collimated beam from mirror (pm1) towards a second parabolic mirror (pm2) (see Fig. 7), which will provide to re-focalise the beam inside the same integrating sphere (is3). For this measurement, it is required the knowledge of the spectral reflectance of (pm2). | Figure 7. Schematic of the experimental configuration A applied to the measure of the flux at 0° incidence. A similar schematic applies for the experimental configuration B |

| Figure 8. A plastic globe is undergoing manufacture for the coating of the inner layer of BaSO4 |

| Figure 9. Photo of the apparatus for DCM measurements with configuration A |

| Figure 10. Intensity distribution of light on the cross section of the quasi-collimated beam produced for DCM in the configuration A |

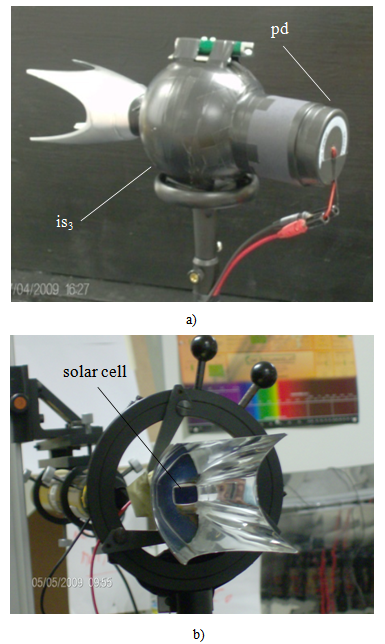

| Figure 12. a) Photo of the Rondine Gen1 closed on the integrating sphere (is3) (SPHERE mode); b) Photo of the Rondine Gen1closed on the high efficiency solar cell (CELL mode) |

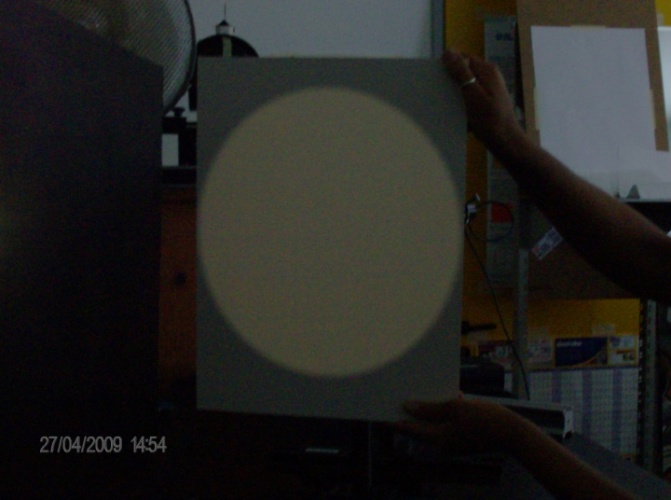

| Figure 13. Projection of the parallel beam on a lambertian diffuser after reflection from pm1 |

| Figure 14. Plot of the intensity of light measured on a 100x100mm2 square cross section of the parallel beam after reflection from pm1 |

4. “Inverse” Characterization Method

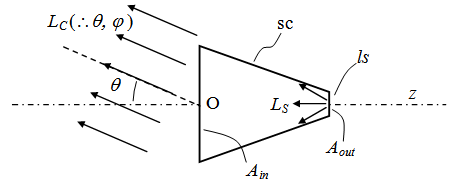

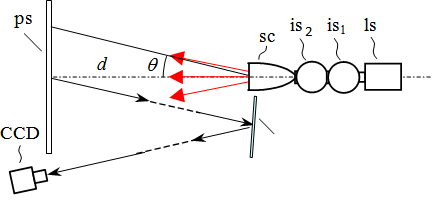

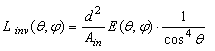

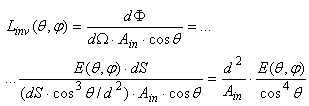

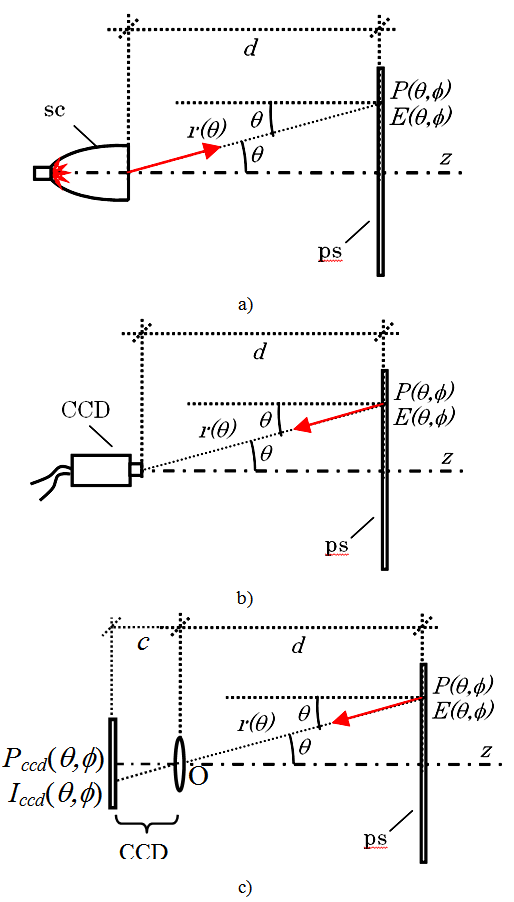

- The “inverse” method, initially known as ILLUME (Inverse Illumination Method), was later revisited and improved, assigning the new name of “Inverse Lambertian Method” (ILM). The theoretical details are given in ref. [6]. The ILM greatly simplifies the experimental apparatus for measuring the angle-resolved transmission efficiency, both relative and absolute, and drastically reduces the number of measurements. The method consists in irradiating the concentrator (sc) in a reverse way by placing a planar Lambertian light source (ls) of uniform radiance LS at the exit aperture, and in measuring the radiance Linv(θ, φ) of the light emitted by the concentrator from the input aperture as function of the different orientation in space, characterized by the polar emission angle θ and the azimuthal emission angle φ (see Fig. 15) (here we use for simplicity the same symbols for the angular direction of the rays incoming to and out coming from the input aperture). When inversely illuminated, the concentrator becomes a light source whose radiance will no longer be constant, because the concentrator changes the angular distribution of the rays emitted by the lambertian source (ls), before they are emitted from the entrance opening.

| Figure 15. Basic scheme of the inverse lambertian method (ILM) |

| Figure 16. Schematic of the experimental ILM apparatus |

| (5) |

| (6) |

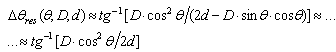

, it may happen that the optics of the CCD is not always adequate to capture the entire inverse image at the distance d between concentrator and screen. In this case, that we have effectively experienced, it is possible to double the optical path between the screen and the CCD interposing a mirror (mi) between the CCD and the screen, as shown in Fig. 17.

, it may happen that the optics of the CCD is not always adequate to capture the entire inverse image at the distance d between concentrator and screen. In this case, that we have effectively experienced, it is possible to double the optical path between the screen and the CCD interposing a mirror (mi) between the CCD and the screen, as shown in Fig. 17.  | Figure 17. When the full inverse image on the screen cannot be captured by the CCD objective, then the help of a mirror (mi) can double the optical path between screen and CCD |

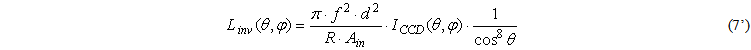

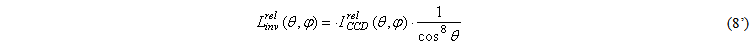

on the planar screen is transformed into the radiance Linv(θ, φ) of the concentrator by the following expression (see the Appendix):

on the planar screen is transformed into the radiance Linv(θ, φ) of the concentrator by the following expression (see the Appendix): | (7) |

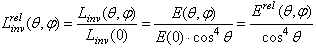

, that is the radiance normalized to the 0° value, it is sufficient to measure the normalized irradiance on the screen,

, that is the radiance normalized to the 0° value, it is sufficient to measure the normalized irradiance on the screen,  :

: | (8) |

where f is the focal length of CCD and R the reflectivity of the lambertian screen. The normalized radiance now becomes:

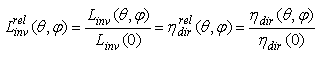

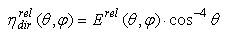

where f is the focal length of CCD and R the reflectivity of the lambertian screen. The normalized radiance now becomes: We have demonstrated [6, 8-11, 13, 15, 18] that the relative inverse radiance profile

We have demonstrated [6, 8-11, 13, 15, 18] that the relative inverse radiance profile  coincides with the relative optical efficiency profile

coincides with the relative optical efficiency profile  of the concentrator operating in the direct mode (DCM) when the direct beam is strictly parallel. When the direct beam is not strictly parallel, we have to take account of its divergence and to put it as the uncertainty on the measured efficiency. We have therefore for the optical efficiency of the concentrator:

of the concentrator operating in the direct mode (DCM) when the direct beam is strictly parallel. When the direct beam is not strictly parallel, we have to take account of its divergence and to put it as the uncertainty on the measured efficiency. We have therefore for the optical efficiency of the concentrator: | (9) |

is obtained from Eq. (8) or (8’) depending if we are operating with a simulation program or with experimental measurements. We conclude this part highlighting the fact that the radiance

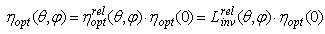

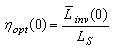

is obtained from Eq. (8) or (8’) depending if we are operating with a simulation program or with experimental measurements. We conclude this part highlighting the fact that the radiance  summarizes all information relating to the light collection properties of the concentrator in relation to its orientation with respect to the solar disk.The inverse method as discussed until now seems to allow determining only the relative angle-resolved optical efficiency of the concentrator, by processing the intensity image produced on the planar screen by the concentrator irradiated in the inverse way. To obtain the absolute efficiency as indicated by Eq. (9), we should ask the direct method for help to measure the on-axis optical efficiency

summarizes all information relating to the light collection properties of the concentrator in relation to its orientation with respect to the solar disk.The inverse method as discussed until now seems to allow determining only the relative angle-resolved optical efficiency of the concentrator, by processing the intensity image produced on the planar screen by the concentrator irradiated in the inverse way. To obtain the absolute efficiency as indicated by Eq. (9), we should ask the direct method for help to measure the on-axis optical efficiency  . If it were really so, we should need to set-up also the direct method apparatus just for one measurement, and the advantages of the inverse method in terms of simplicity of the experimental apparatus should be lost. Fortunately, new developments of the theory [6, 9, 10] provide a way of obtaining

. If it were really so, we should need to set-up also the direct method apparatus just for one measurement, and the advantages of the inverse method in terms of simplicity of the experimental apparatus should be lost. Fortunately, new developments of the theory [6, 9, 10] provide a way of obtaining  also by the inverse method. It can be shown in fact that the on-axis efficiency

also by the inverse method. It can be shown in fact that the on-axis efficiency  can be obtained by the expression:

can be obtained by the expression: | (10) |

and

and  are radiances measured on the image recorded by the CCD camera oriented towards the input aperture of the concentrator irradiated in the inverse mode (ILM) (see the schematic of the apparatus in Fig. 18).

are radiances measured on the image recorded by the CCD camera oriented towards the input aperture of the concentrator irradiated in the inverse mode (ILM) (see the schematic of the apparatus in Fig. 18).  is the average radiance of the whole input aperture, whereas

is the average radiance of the whole input aperture, whereas  is the radiance of the receiver, the exit aperture, corresponding to the radiance of the Lambertian source.

is the radiance of the receiver, the exit aperture, corresponding to the radiance of the Lambertian source. becomes independent of that of

becomes independent of that of  and requires the removal of those components. As the optical efficiency

and requires the removal of those components. As the optical efficiency  ≤ 1, we will always have

≤ 1, we will always have  ≤

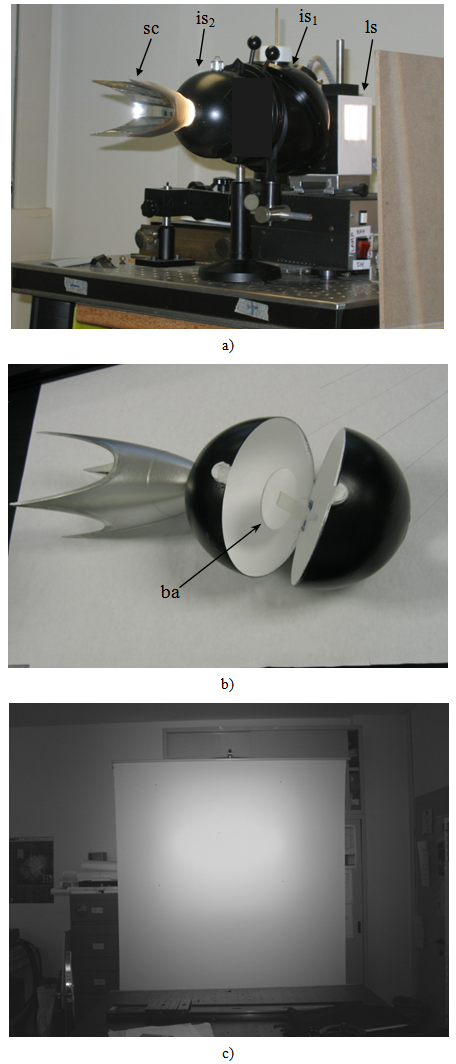

≤  .To produce the Lambertian source on the back of the concentrator (sc), we can use a light source (ls) and a pair of integrating spheres (is1) and (is2) as already done when applying the direct method (see Fig. 19a). A Xenon arc lamp is the best choice to simulate the direct solar spectrum, whereas the integrating sphere is the best choice to obtain a lambertian light source [43-47]. The concentrator is grafted on to the output window of (is2) as shown in Fig. 19b, where it is also shown the “baffle” (ba) at the centre of the sphere. The baffle has the function to filter the direct light coming from sphere (is1) and assures a lambertian distribution of light at the exit window of (is2). The planar screen is placed in laboratory at a proper distance from the source and there the characteristic light image, leaved by the inverse beam as a fingerprint, is produced (see Fig. 19c).

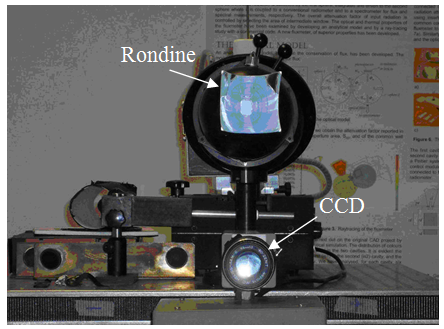

.To produce the Lambertian source on the back of the concentrator (sc), we can use a light source (ls) and a pair of integrating spheres (is1) and (is2) as already done when applying the direct method (see Fig. 19a). A Xenon arc lamp is the best choice to simulate the direct solar spectrum, whereas the integrating sphere is the best choice to obtain a lambertian light source [43-47]. The concentrator is grafted on to the output window of (is2) as shown in Fig. 19b, where it is also shown the “baffle” (ba) at the centre of the sphere. The baffle has the function to filter the direct light coming from sphere (is1) and assures a lambertian distribution of light at the exit window of (is2). The planar screen is placed in laboratory at a proper distance from the source and there the characteristic light image, leaved by the inverse beam as a fingerprint, is produced (see Fig. 19c). | Figure 21. Photo of the Rondine during ILM measurements. The CCD is placed just below at short distance |

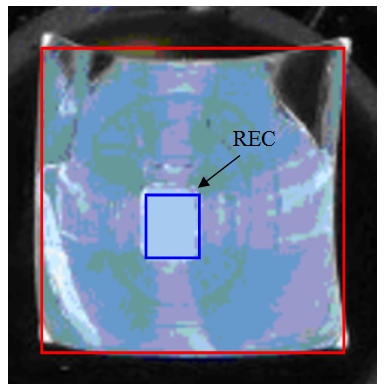

is equal to the ratio between the average intensity of the red region and the uniform intensity of the blue region.

is equal to the ratio between the average intensity of the red region and the uniform intensity of the blue region. | Figure 22. Image of the front side (on-axis) input aperture of Rondine1. The blue frame surrounds the area of the receiver (REC); the red frame surrounds the total input area |

| (11) |

. Eq. (11) applies at any distance between the CCD and the concentrator, since the radiance is constant with distance.

. Eq. (11) applies at any distance between the CCD and the concentrator, since the radiance is constant with distance. 5. Experimental and Simulated Results

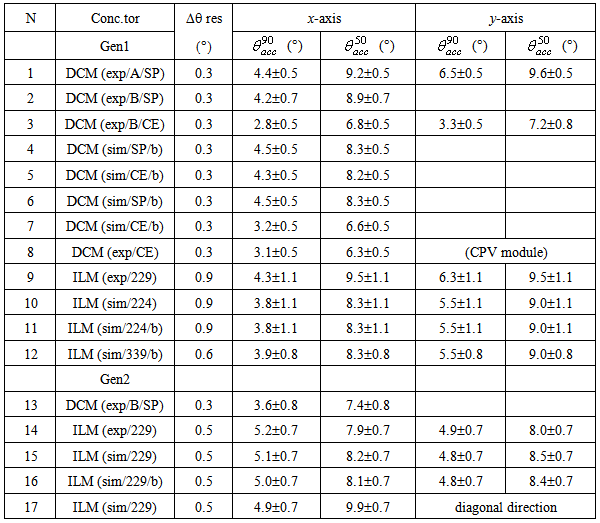

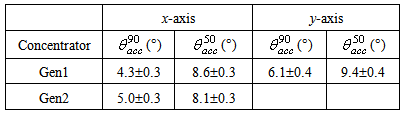

5.1. Transmission Efficiency by the Direct Method

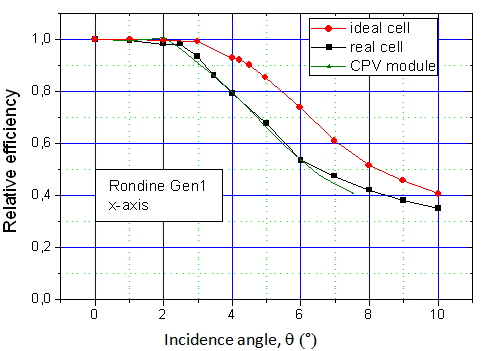

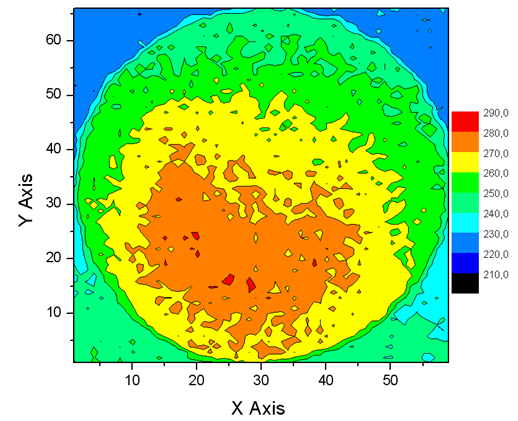

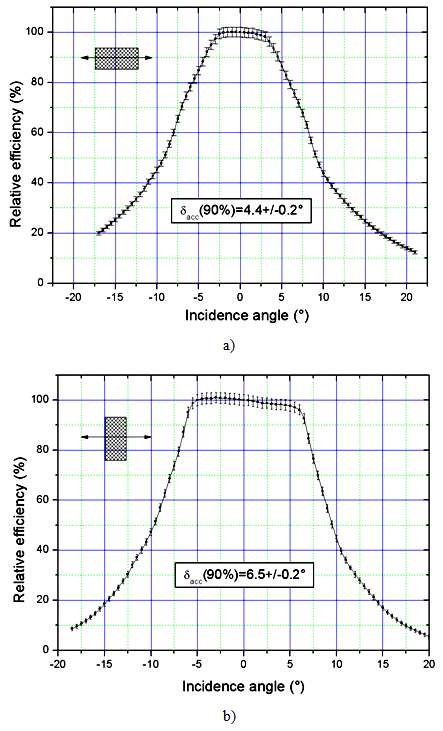

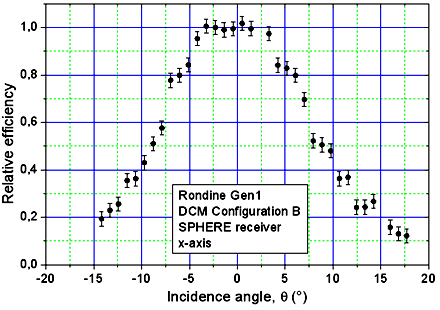

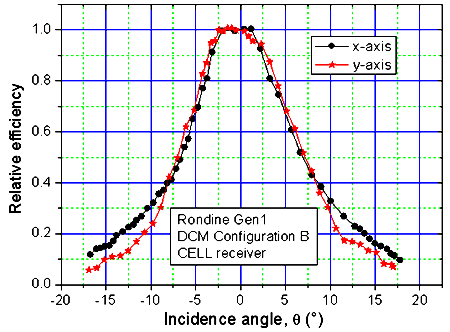

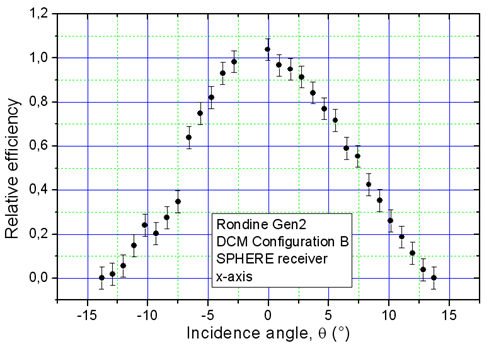

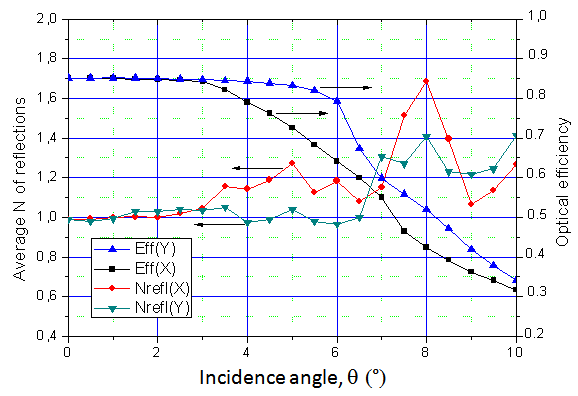

- We start discussing the results of measurements made by the DCM, configuration A. Fig. 23 shows the experimental curves of optical efficiency obtained for the Rondine Gen1 concentrator. The dashed rectangle represents the exit aperture of the concentrator and the arrow indicates the direction of the plane of incidence of the quasi-parallel beam. The exit aperture of the concentrator however is not a simple rectangle as the corners are smoothed (see Fig. 2a). The x-profile (y-profile) has been traced parallel to the major (minor) edge of the exit aperture. Fig. 23 shows that the x-profile and y-profile are slightly distorted, as expected as an effect of lack of symmetry of the intensity distribution of the parallel beam (see Fig. 10). The acceptance angles measured for the x-profile and y-profile at 90% of the 0° efficiency are 4.4±0.2° and 6.5±0.2°, respectively. The acceptance angles measured for the x-profile and y-profile at 50% of the 0° efficiency are 9.2±0.2° and 9.6±0.2°, respectively. As it can be seen from Fig. 23b, the y-axis efficiency at 0° does not correspond to the maximum value, due to the slight distortion of the profile. The errors assigned to the acceptance angles are random errors derived from the intensity measurements carried out by the CCD camera inside the integrating sphere (is3), so they do not include systematic errors like those introduced by the use of a non perfectly symmetric and uniform beam (see Fig. 10), nor the angular divergence imposed to the beam.

| Figure 23. a) Relative efficiency of the Rondine Gen1 concentrator traced along the x-axis. b) Relative efficiency of the Rondine Gen1 concentrator traced along the y-axis |

| Figure 24. Normalized efficiency of Rondine Gen1 traced along the x-axis with the DCM, configuration B, and SPHERE type receiver |

| Figure 25. Relative efficiency of Rondine Gen1 traced along the x-axis and y-axis with the DCM, configuration B, and CELL receiver |

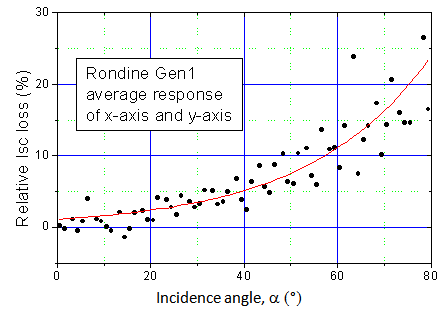

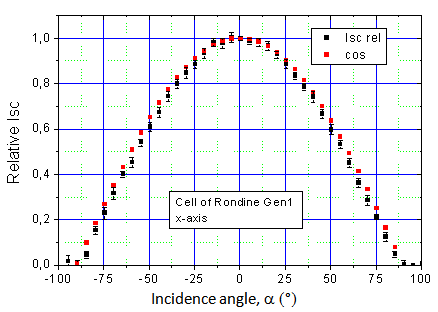

| Figure 27. Plot of the short-circuit current Isc of the Rondine Gen1 cell, normalized to 0° incidence, as function of the polar incidence angle α. The Isc is compared to the cosine function |

| (12) |

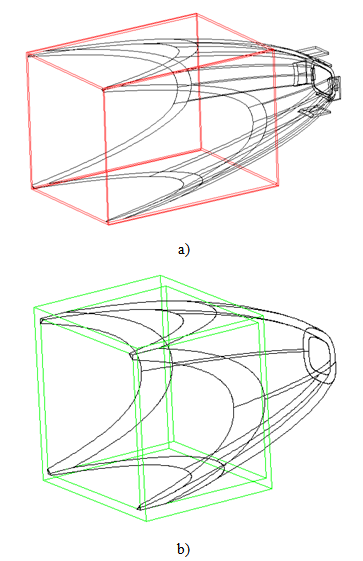

| Figure 29. CAD model of Rondine Gen1 (a) and Rondine Gen2 (b) after the addition on the front aperture of four planar ideal mirrors. The two prototypes are shown with a different scale |

| (13) |

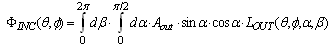

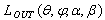

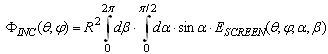

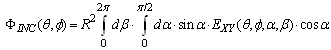

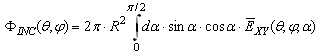

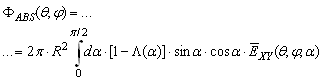

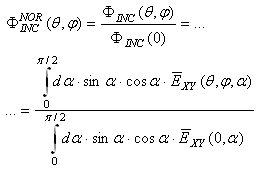

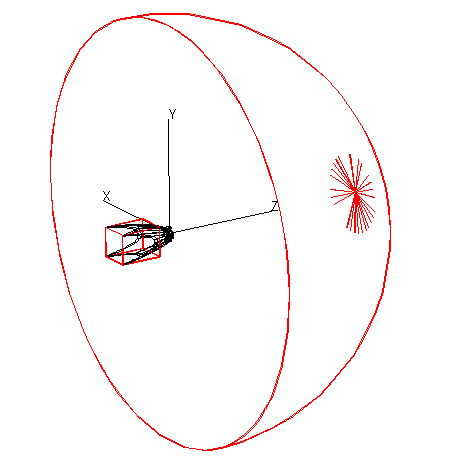

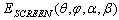

is the radiance of the light emitted from the exit opening. The flux ΦINC(θ, φ) can be expressed as function of the irradiance measured on the hemispherical screen (see Section 5.6), ESCREEN (θ, φ, α, β):

is the radiance of the light emitted from the exit opening. The flux ΦINC(θ, φ) can be expressed as function of the irradiance measured on the hemispherical screen (see Section 5.6), ESCREEN (θ, φ, α, β): | (14) |

| (15) |

. The flux ΦINC(θ, φ) now becomes:

. The flux ΦINC(θ, φ) now becomes: | (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

of Eq. (18) and the function

of Eq. (18) and the function  of Eq. (19) for the x-axis (φ = 0; long edge of the exit aperture) of the Rondine Gen1. They are reported in Fig. 30.

of Eq. (19) for the x-axis (φ = 0; long edge of the exit aperture) of the Rondine Gen1. They are reported in Fig. 30. we measure an acceptance angle of 4.5±0.2° at 90% of 0° efficiency and 8.3±0.2° at 50% of 0° efficiency. For the function

we measure an acceptance angle of 4.5±0.2° at 90% of 0° efficiency and 8.3±0.2° at 50% of 0° efficiency. For the function  we measure an acceptance angle of 4.3±0.2° at 90% of 0° efficiency and 8.2±0.2° at 50% of 0° efficiency. The two functions

we measure an acceptance angle of 4.3±0.2° at 90% of 0° efficiency and 8.2±0.2° at 50% of 0° efficiency. The two functions  and

and  are practically overlapping and no shrinkage of the curve

are practically overlapping and no shrinkage of the curve  is observed; this means that the effect of the angle of incidence of light focused from Rondine Gen1 on the solar cell is negligible and does not alter the shape of the

is observed; this means that the effect of the angle of incidence of light focused from Rondine Gen1 on the solar cell is negligible and does not alter the shape of the  curve compared to the

curve compared to the  curve. This behaviour is expected also for

curve. This behaviour is expected also for  and

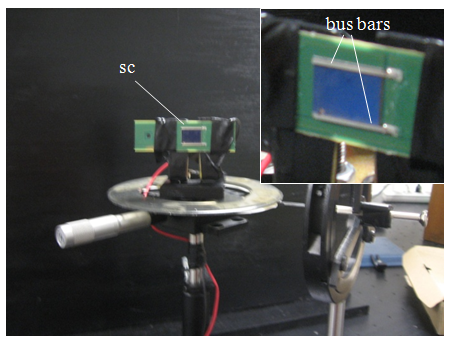

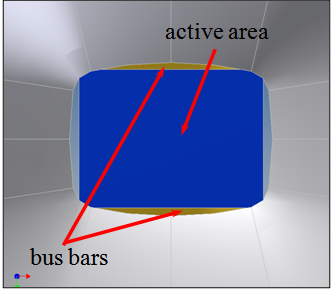

and  (y-axis), because the Λ(α) function is the same for the two azimuthal orientations. This confirms our assumption that the optical loss (narrowing of the transmission efficiency curve) associated with the transition from the SPHERE to the CELL mode operation, does not depend on the optical loss of the bare solar cell, and then must be sought elsewhere. Watching carefully the status of receiver in the Rondine Gen1, we noticed that the coupling between the concentrator and the solar cell is not optimal. In fact, for the characterization work, we used as receiver a bare solar cell, the same mounted in the module, but without encapsulation and just placed faced to the exit opening. The result is that the active area of the cell does not completely fill the exit opening, so part of light is lost at the periphery of the cell, causing the reduction of the transmission efficiency, as observed experimentally (see Fig. 25). The fact is illustrated in Fig. 31, where it is shown the detail of the receiver in the Rondine Gen1. The bus bars affect mainly the y-axis operation of the concentrator, as they are exposed to the concentrated light in the upper and lower part of the receiver; also the x-axis is affected by the slightly shorter length of the cell respect to the exit opening. We expect therefore to have shrinkage of the efficiency curve along both the x-axis (long edge of exit aperture) and y-axis (short edge of exit aperture), as it was effectively observed (see Fig. 25).

(y-axis), because the Λ(α) function is the same for the two azimuthal orientations. This confirms our assumption that the optical loss (narrowing of the transmission efficiency curve) associated with the transition from the SPHERE to the CELL mode operation, does not depend on the optical loss of the bare solar cell, and then must be sought elsewhere. Watching carefully the status of receiver in the Rondine Gen1, we noticed that the coupling between the concentrator and the solar cell is not optimal. In fact, for the characterization work, we used as receiver a bare solar cell, the same mounted in the module, but without encapsulation and just placed faced to the exit opening. The result is that the active area of the cell does not completely fill the exit opening, so part of light is lost at the periphery of the cell, causing the reduction of the transmission efficiency, as observed experimentally (see Fig. 25). The fact is illustrated in Fig. 31, where it is shown the detail of the receiver in the Rondine Gen1. The bus bars affect mainly the y-axis operation of the concentrator, as they are exposed to the concentrated light in the upper and lower part of the receiver; also the x-axis is affected by the slightly shorter length of the cell respect to the exit opening. We expect therefore to have shrinkage of the efficiency curve along both the x-axis (long edge of exit aperture) and y-axis (short edge of exit aperture), as it was effectively observed (see Fig. 25). | Figure 31. a) Particular of the solar cell with the horizontal (x-axis) bus bar of the grid; b) The bus bar appears slightly exposed at the exit opening of the Rondine Gen1 |

= 4.5±0.2°,

= 4.5±0.2°,  = 8.3±0.2°, whereas the curve of the non-optimised cell presents the following acceptance angles:

= 8.3±0.2°, whereas the curve of the non-optimised cell presents the following acceptance angles:  = 3.2±0.2°,

= 3.2±0.2°,  = 6.6±0.2°. These results are consistent with what obtained experimentally by operating, respectively, in the in SPHERE mode (ideal absorber = optimised cell) and in the CELL mode (non-optimised real cell).

= 6.6±0.2°. These results are consistent with what obtained experimentally by operating, respectively, in the in SPHERE mode (ideal absorber = optimised cell) and in the CELL mode (non-optimised real cell). | Figure 33. Schematic section of a small region of the Rondine Gen1 CPV module |

| Figure 34. Experimental normalized efficiency of Rondine Gen2 traced with the DCM, configuration B, and SPHERE receiver |

5.2. Transmission Efficiency by the Inverse Method

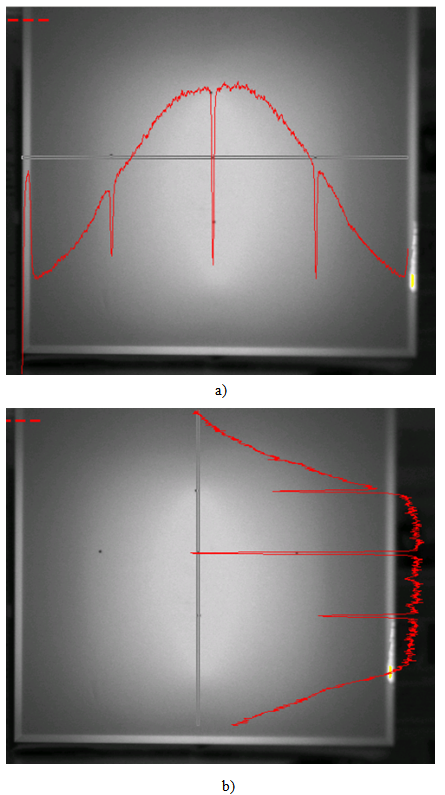

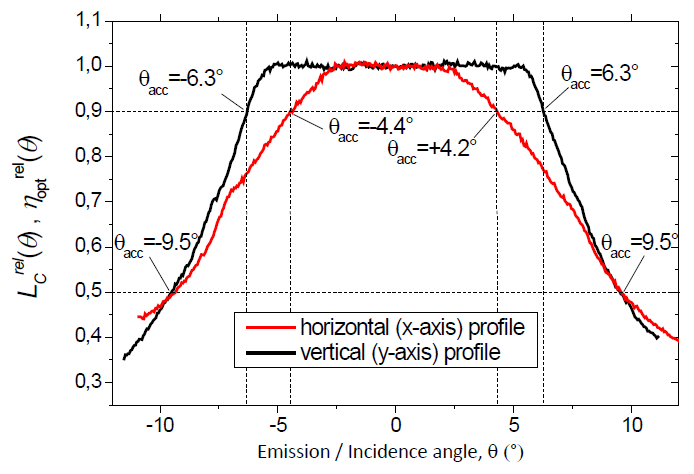

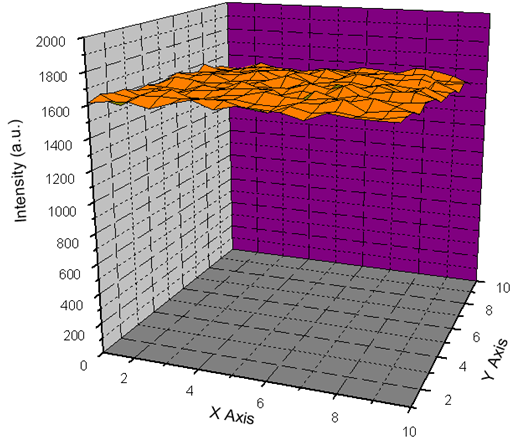

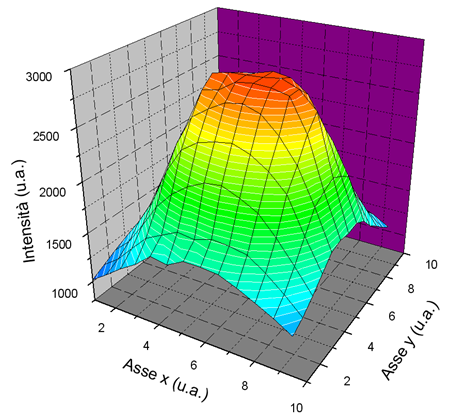

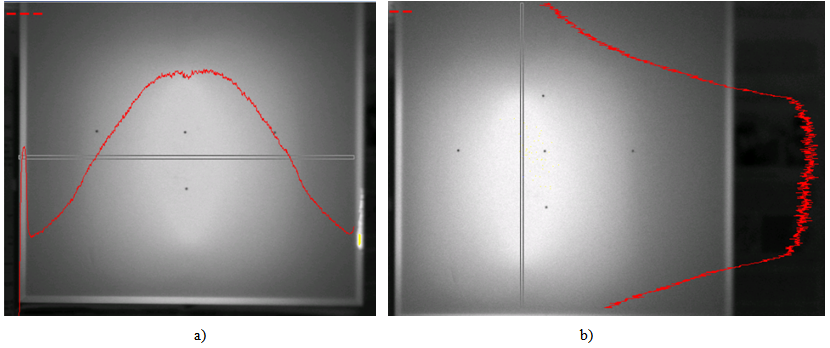

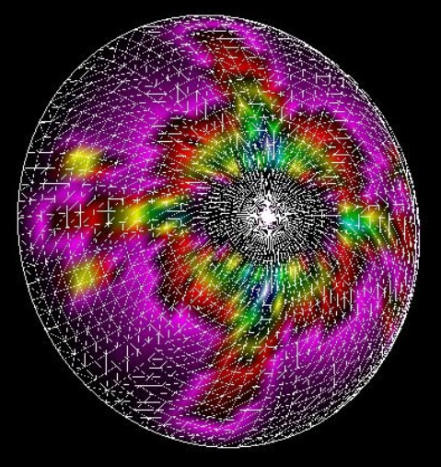

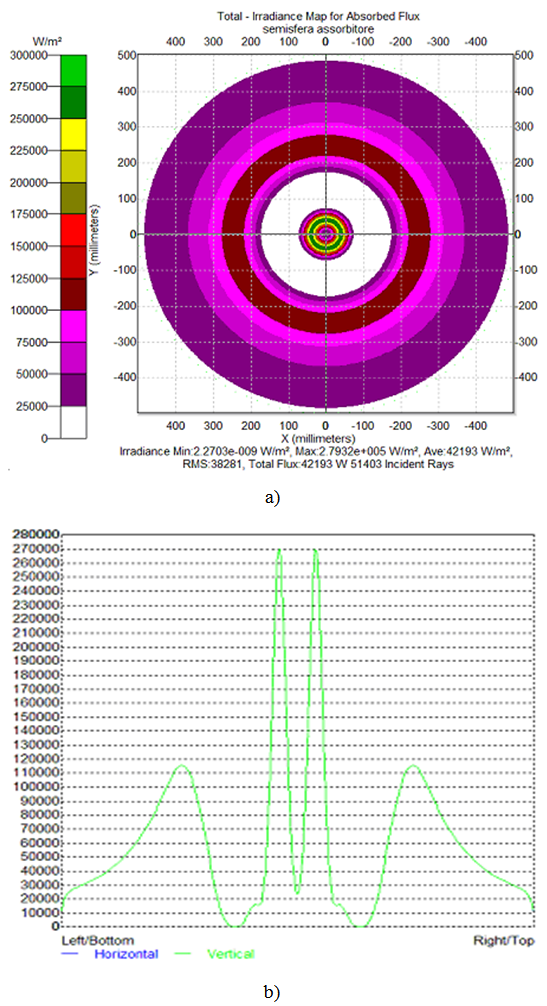

- We discuss here the results of the experimental measurements made by ILM on the Rondine Gen1. The schematic of the experimental apparatus is that reported in Fig. 16. Fig. 35 shows the three-dimensional irradiance map produced on the screen. It represents the quantity EC (θ, φ) introduced in Section 4. It has an elliptical form, reminiscent of the exit opening of rectangular shape. By using HiPic, we drew the horizontal and vertical profiles of the irradiance on the screen (see Fig. 36). Differently from the calibration profiles of Fig. 20, these profiles were traced centering the inverse image and avoiding the black dots. Normalizing EC (θ, φ) and applying Eq. (8), we finally obtain the normalized radiance

, equivalent to the normalized efficiency

, equivalent to the normalized efficiency  (see Eq. (9)).

(see Eq. (9)).  | Figure 35. Three-dimensional view of the irradiance map produced on the screen by the inverse light from Rondine Gen1 |

| Figure 36. Analysis by HiPic of the ILM image produced by Rondine Gen1. The irradiance profiles (red lines) are traced along the horizontal (x-axis) (a) and vertical (y-axis) (b) directions |

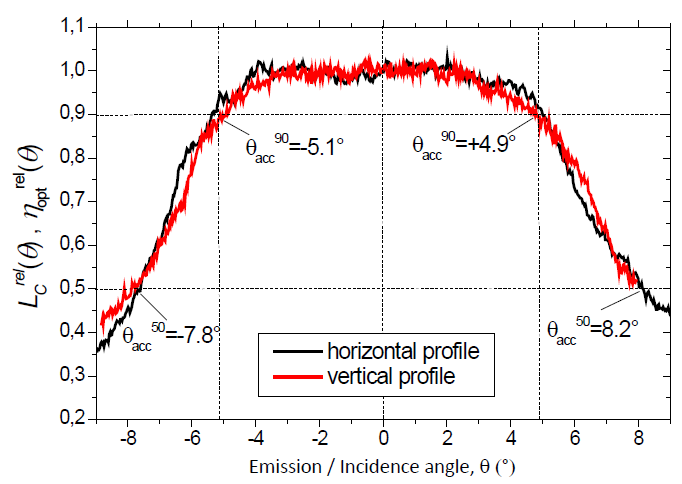

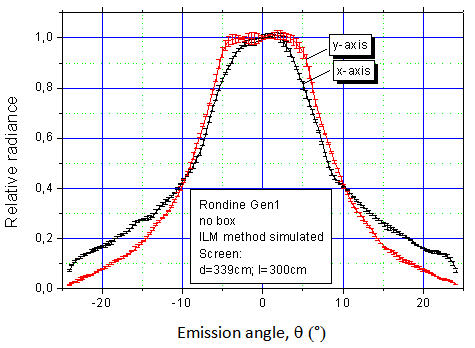

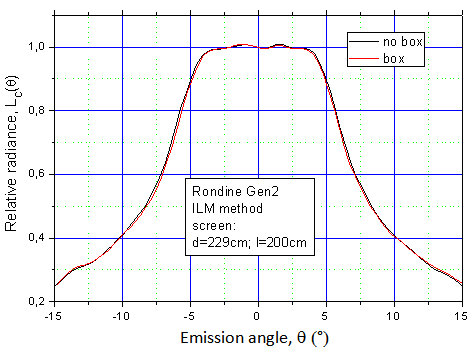

has been calculated for two crossed azimuthal directions, the horizontal (x) and vertical (y) axes, parallel to the edge of input aperture, and are shown in Fig. 37.The measured acceptance angles are: 4.3±0.2° (x-axis) and 6.3±0.2° (y-axis) at 90% of 0° efficiency and 9.5±0.2° for both axes at 50% of 0° efficiency, in good agreement with the experimental results of direct method configuration A (see Fig. 23) and configuration B, SPHERE receiver (see Fig. 24).

has been calculated for two crossed azimuthal directions, the horizontal (x) and vertical (y) axes, parallel to the edge of input aperture, and are shown in Fig. 37.The measured acceptance angles are: 4.3±0.2° (x-axis) and 6.3±0.2° (y-axis) at 90% of 0° efficiency and 9.5±0.2° for both axes at 50% of 0° efficiency, in good agreement with the experimental results of direct method configuration A (see Fig. 23) and configuration B, SPHERE receiver (see Fig. 24).  | Figure 40. Relative angle-resolved radiance of emission of the Rondine Gen1 without side box, irradiated by the ILM method, traced along the x-axis (dark line) and the y-axis (red line) |

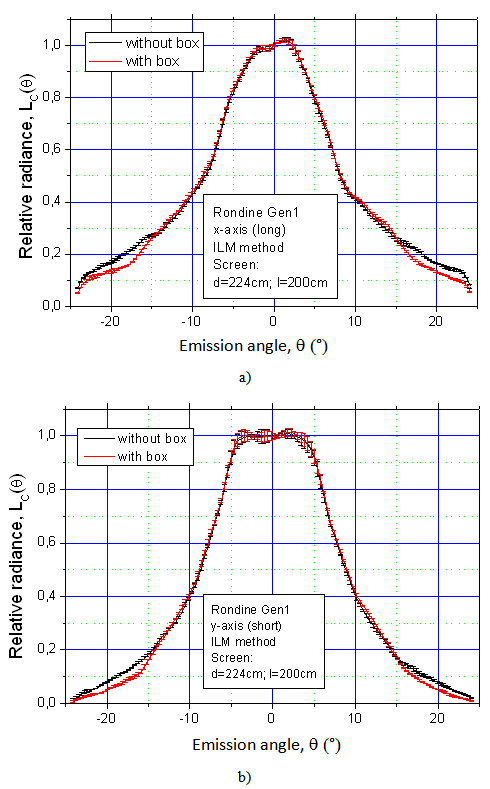

, normalized as

, normalized as  and finally transformed into the relative radiance

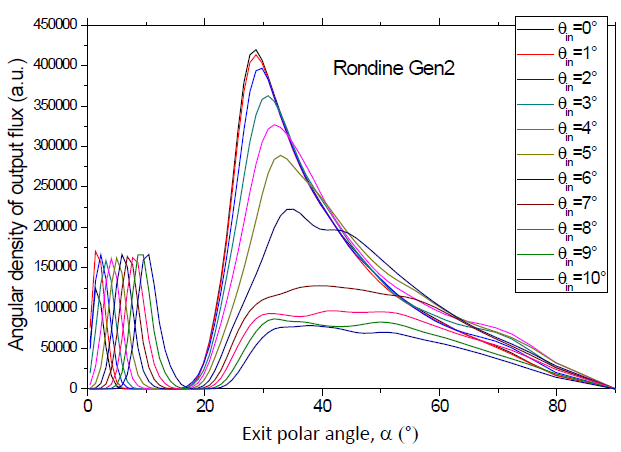

and finally transformed into the relative radiance  following Eq. (8). The radiance profiles, equivalent to the transmission efficiency

following Eq. (8). The radiance profiles, equivalent to the transmission efficiency  , extracted for the x and y directions overlap very well, demonstrating the accuracy of the optical fabrication process of Rondine Gen2. The measured acceptance angles are: 5.1±0.2° (x-axis) and 4.8±0.2° (y-axis) at 90% of 0° efficiency and 8.2±0.2° (x-axis) and 8.5±0.2° (y-axis) at 50% of 0° efficiency, in good agreement with the experimental results. The inverse radiance was simulated also for the Rondine Gen2+box and the resulting curves, averaged over the x and y-axes, are compared in Fig. 42. Fig. 42 shows that the real Rondine Gen2 concentrator, whose side planar walls were removed (see Fig. 2), behaves exactly as it had the same walls as ideal mirrors.

, extracted for the x and y directions overlap very well, demonstrating the accuracy of the optical fabrication process of Rondine Gen2. The measured acceptance angles are: 5.1±0.2° (x-axis) and 4.8±0.2° (y-axis) at 90% of 0° efficiency and 8.2±0.2° (x-axis) and 8.5±0.2° (y-axis) at 50% of 0° efficiency, in good agreement with the experimental results. The inverse radiance was simulated also for the Rondine Gen2+box and the resulting curves, averaged over the x and y-axes, are compared in Fig. 42. Fig. 42 shows that the real Rondine Gen2 concentrator, whose side planar walls were removed (see Fig. 2), behaves exactly as it had the same walls as ideal mirrors. | Figure 41. ILM map of irradiance produced on the planar screen by the inverse light from Rondine Gen2 (no box) at d = 229 cm |

| Figure 42. Simulated inverse radiances vs. emission angle of Rondine Gen2, with and without box, averaged over the x and y directions, with the ILM method at d = 229 cm |

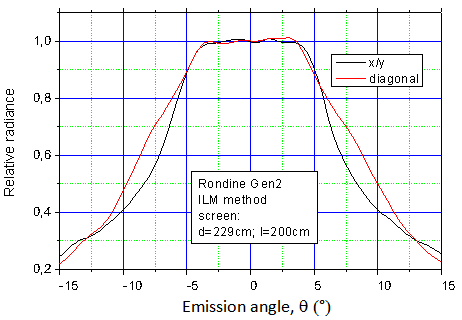

≈ 5.0±0.2°,

≈ 5.0±0.2°,  ≈ 8.4±0.2°, diagonal direction:

≈ 8.4±0.2°, diagonal direction:  = 4.9±0.2°,

= 4.9±0.2°,  = 9.9±0.2°. Then, in order to increase the collection capability of the Rondine Gen2 along the direction of tracking, it could be convenient to have the tracking direction parallel to the diagonal of the opening entrance. This is valid for misalignments >

= 9.9±0.2°. Then, in order to increase the collection capability of the Rondine Gen2 along the direction of tracking, it could be convenient to have the tracking direction parallel to the diagonal of the opening entrance. This is valid for misalignments > , because, as it can be seen in Fig. 43,

, because, as it can be seen in Fig. 43,  is improved of ≈ 20%, but

is improved of ≈ 20%, but  remains constant.

remains constant.  | Figure 43. Simulated inverse radiances vs. emission angle of Rondine Gen2, calculated along the x/y direction and along the diagonal direction, with the ILM method at d = 229 cm |

|

, obtained experimentally. The on-axis front image of Rondine Gen1 input aperture is shown in Fig. 22. It is clearly visible the central rectangular region of the receiver (the exit aperture). The radiance of the receiver in Fig. 22 is slightly underestimated due to the presence of the baffle at the centre (see Fig. 19b). By correcting this effect, we obtain a better estimate of

, obtained experimentally. The on-axis front image of Rondine Gen1 input aperture is shown in Fig. 22. It is clearly visible the central rectangular region of the receiver (the exit aperture). The radiance of the receiver in Fig. 22 is slightly underestimated due to the presence of the baffle at the centre (see Fig. 19b). By correcting this effect, we obtain a better estimate of  which, together with the average radiance

which, together with the average radiance  of the whole image, gives

of the whole image, gives  = 84.0±1.0% (see Eq. (10)). For the Rondine Gen2 concentrator we obtain

= 84.0±1.0% (see Eq. (10)). For the Rondine Gen2 concentrator we obtain  = 86.0±1.0%.

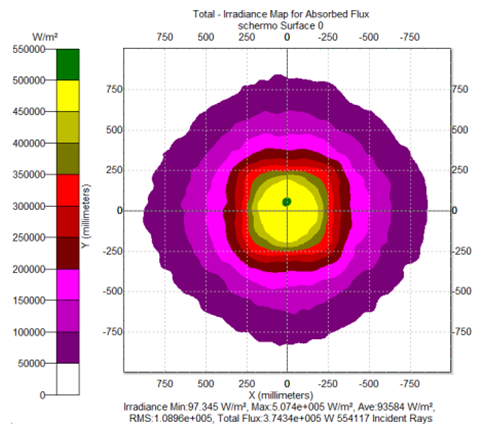

= 86.0±1.0%.5.3. Flux Distribution on the Receiver

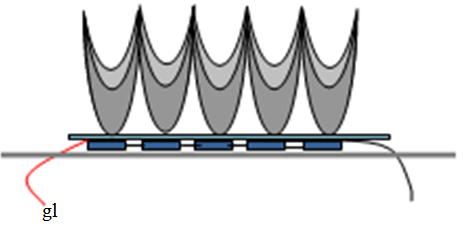

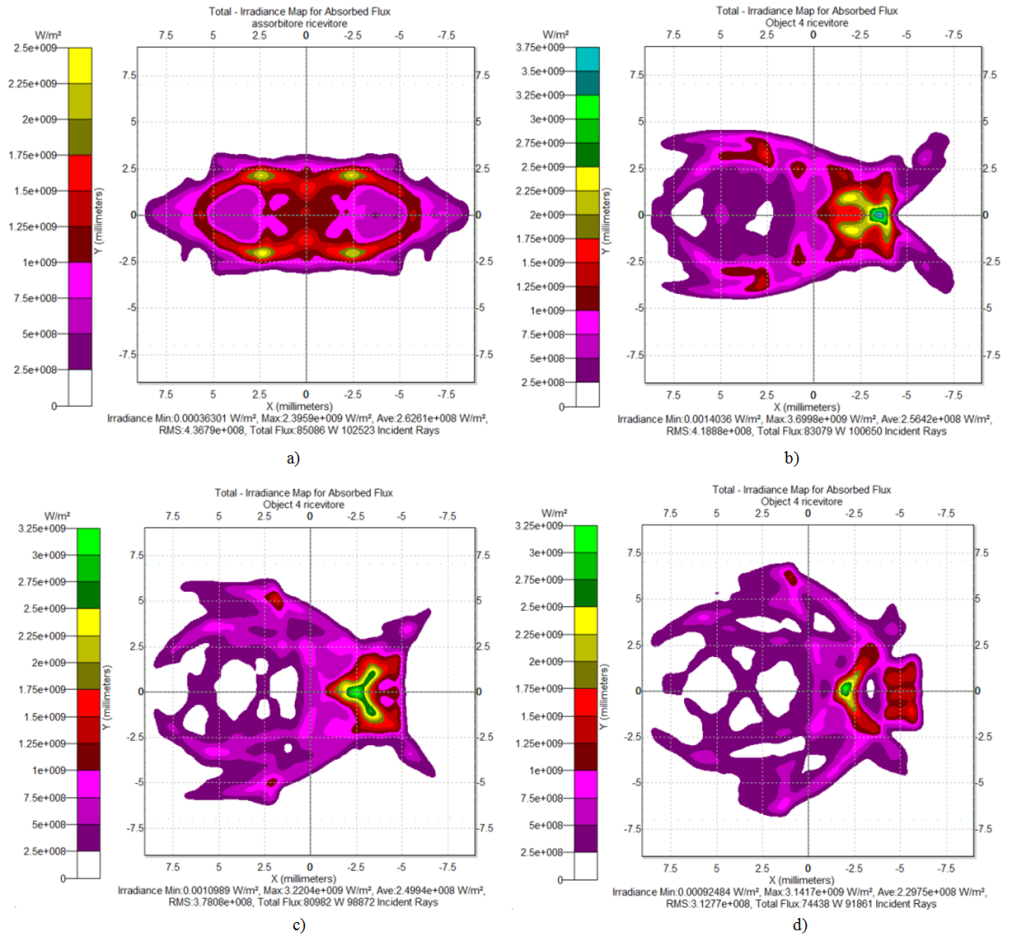

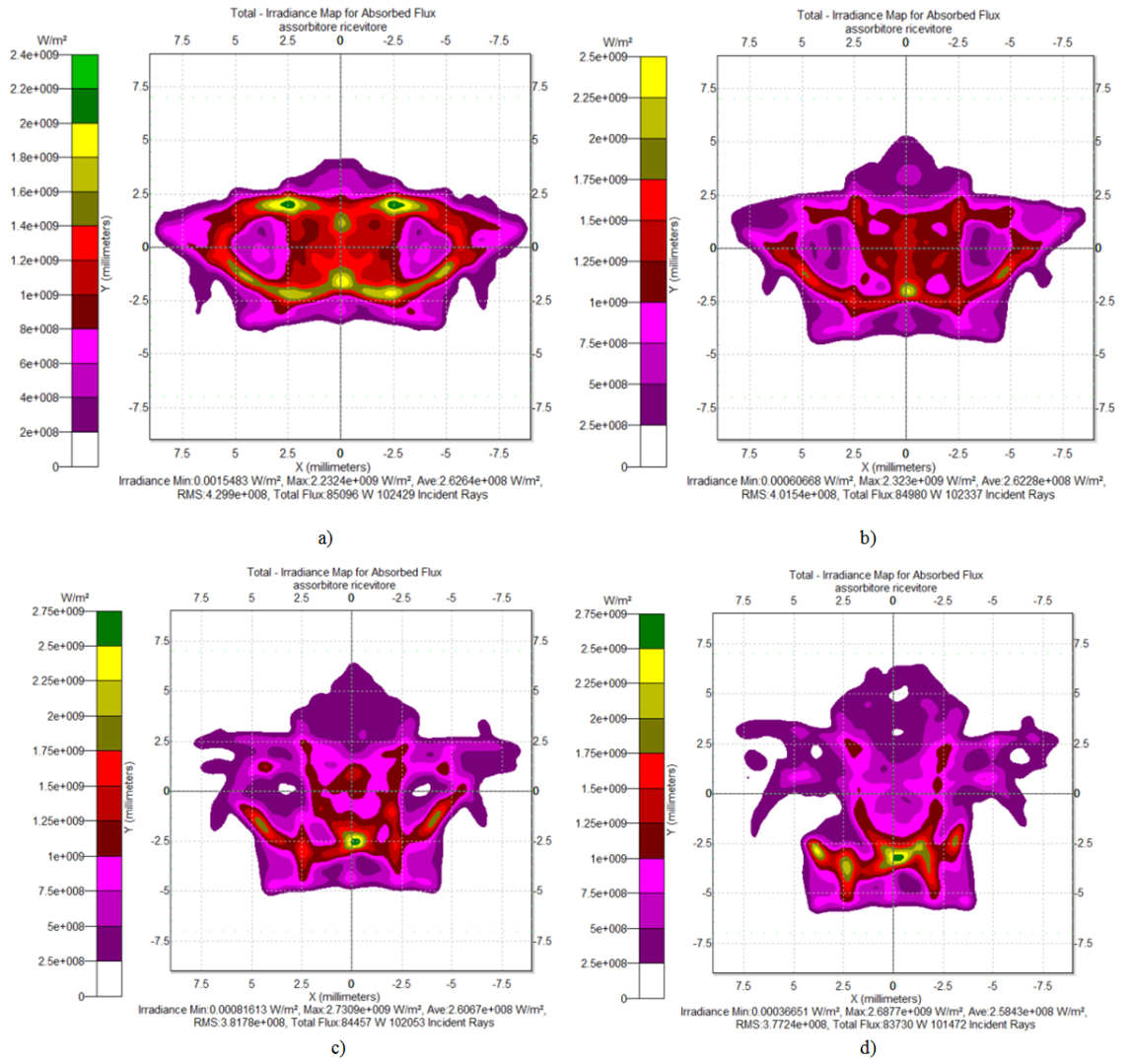

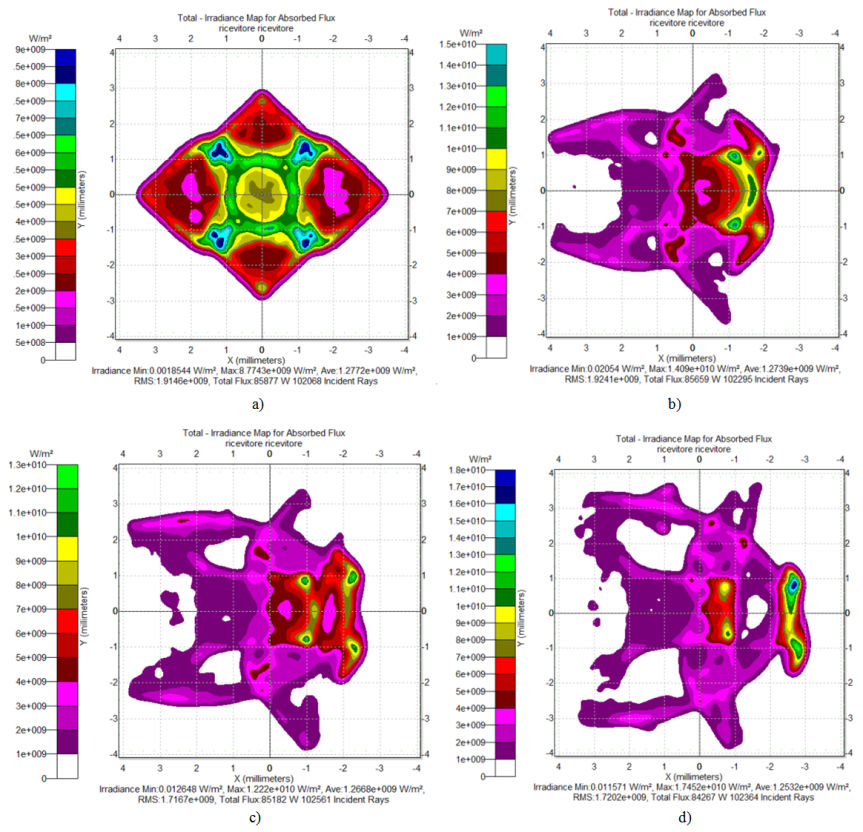

- The analysis of the spatial distribution of output flux from a PV concentrator is important because of its strong influence on the conversion efficiency [39, 50-53]. As it has been demonstrated in previous works [7, 38], a canonical 3D-CPC, aligned with the Sun, presents an unacceptable flux distribution, mainly focused on the optical axis. To work around this problem, the Rondine concentrator, belonging to the class of the light cones, was obtained modifying a 3D-CPC as follows: by truncating it, deforming the lateral surface, squaring the entrance opening and finally removing the lateral walls (see Fig. 2). The effect of this CPC redesign is the mixing of rays and a better distribution of flux, particularly when the Rondine is aligned with the Sun (θ = 0°). We start considering the Rondine Gen1. Fig. 44 shows the simulated maps of irradiance on the receiver at different angles of incidence of a collimated beam in direction of the x-axis.Fig. 45 shows other simulated maps for the collimated beam bent at different angles towards the y-axis. Fig. 46 shows some simulated maps of irradiance on the receiver for the Rondine Gen2. From Figs. 44-46 we see, first of all, that the output flux is distributed well on the receiver when the Rondine is aligned with the Sun; in addition, the flux distribution affects the entire surface of the receiver even for angles of incidence within the acceptance angle

. The geometry of the two Rondine concentrators, therefore, does not require a secondary mixer, normally used in combination with a cone of light as a CPC.

. The geometry of the two Rondine concentrators, therefore, does not require a secondary mixer, normally used in combination with a cone of light as a CPC.  | Figure 44. Maps of irradiance of Rondine Gen1 output flux at some incidence angles of the collimated beam along x-axis: 0.0° (a), 2.0° (b), 3.0° (c), 4.0° (d). Number of input rays: 100k |

| Figure 45. Maps of irradiance of Rondine Gen1 output flux at some incidence angles of the collimated beam along y-axis: 1.0° (a), 2.0° (b), 3.0° (c), 4.0° (d). Number of input rays: 100k |

| Figure 46. Maps of irradiance of Rondine Gen2 output flux at some incidence angles of the collimated beam: 0.0° (a), 2.0° (b), 3.0° (c), 4.0° (d). Number of input rays: 100k |

5.4. Number of Reflections of Transmitted Rays

- In an ideal 3D-CPC concentrator, the average number of reflections is low and almost constant with the incidence angle within

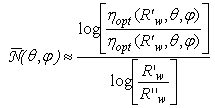

[7]. In the case of Rondine concentrator, the length was defined to obtain about only one reflection for the entering rays parallel to the optical axis, to reduce the optical losses by multiple reflections. The procedure used by us to estimate the average number of reflections of the transmitted rays of a collimated beam incident at different angles is discussed in a previous work [7]. Here we simply bring the final formula:

[7]. In the case of Rondine concentrator, the length was defined to obtain about only one reflection for the entering rays parallel to the optical axis, to reduce the optical losses by multiple reflections. The procedure used by us to estimate the average number of reflections of the transmitted rays of a collimated beam incident at different angles is discussed in a previous work [7]. Here we simply bring the final formula: | (20) |

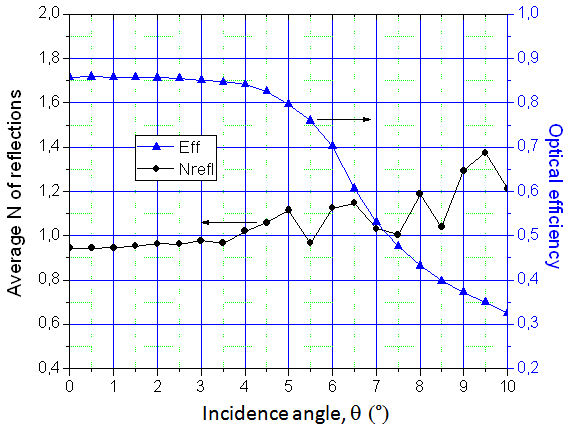

is the average number of reflections. To apply Eq. (20), we have carried out a fast series of DCM simulations to get the optical efficiency of Rondine vs. the polar angle for reflectances R'w = 0.83 and R''w =0.87, close to the specular reflectance of Rondine Rw = 0.85 (see Section 2). Fig. 47 shows that the average number of reflections

is the average number of reflections. To apply Eq. (20), we have carried out a fast series of DCM simulations to get the optical efficiency of Rondine vs. the polar angle for reflectances R'w = 0.83 and R''w =0.87, close to the specular reflectance of Rondine Rw = 0.85 (see Section 2). Fig. 47 shows that the average number of reflections  is equal to one at the optical axis, as expected, then grows and reaches a maximum at around

is equal to one at the optical axis, as expected, then grows and reaches a maximum at around  , as it was also found with an ideal 3D-CPC [7].

, as it was also found with an ideal 3D-CPC [7]. | Figure 47. Simulated curves of absolute optical efficiency of Rondine Gen1 and corresponding curves of average number of reflections obtained by applying Eq. (20). The curves refer to x and y-axes |

maintains always very near to one below the acceptance angle

maintains always very near to one below the acceptance angle  . The optical efficiency at 0° is ~0.85, the same value of the specular reflectance Rw, as required for one reflection. This result agrees with our previous on-axis ILM measurements on Rondine Gen1:

. The optical efficiency at 0° is ~0.85, the same value of the specular reflectance Rw, as required for one reflection. This result agrees with our previous on-axis ILM measurements on Rondine Gen1:  = 0.84±0.01 (see last part of Section 5.3) and represents therefore a further validation of ILM method. Fig. 48 shows the results of average number of reflections for the Rondine Gen2.

= 0.84±0.01 (see last part of Section 5.3) and represents therefore a further validation of ILM method. Fig. 48 shows the results of average number of reflections for the Rondine Gen2.  is now slightly lower than one on the optical axis, effect of the lower concentration ratio of Gen2 respect to Gen1 (see Fig. 3) and of the stronger deformation of the Gen2 geometry respect to the canonical CPC, which reduces multiple reflections of rays near the edges of input aperture [7].

is now slightly lower than one on the optical axis, effect of the lower concentration ratio of Gen2 respect to Gen1 (see Fig. 3) and of the stronger deformation of the Gen2 geometry respect to the canonical CPC, which reduces multiple reflections of rays near the edges of input aperture [7].  shows a monotonic growing with θ, without a maximum at the acceptance angle

shows a monotonic growing with θ, without a maximum at the acceptance angle  as observed in Gen1, probably as a further cause of its strong differentiation from the ideal CPC geometry.

as observed in Gen1, probably as a further cause of its strong differentiation from the ideal CPC geometry. | Figure 48. Simulated curve of absolute optical efficiency of Rondine Gen2 and corresponding curve of average number of reflections obtained by applying Eq. (20) |

= 0.86±0.01 (see last part of Section 5.3).

= 0.86±0.01 (see last part of Section 5.3). 5.5. Angular Distribution of the Transmitted Flux

- To study the angular distribution of the transmitted rays, we have coupled the Rondine with a hemispherical screen, of internal radius R, whose inner wall has been set as an ideal absorber, making coincide the centre of the exit aperture of Rondine with the centre of the hemispherical screen (see Fig. 49).

| Figure 49. Layout of the configuration used for the simulation of the angular distribution of light transmitted by the Rondine Gen1 |

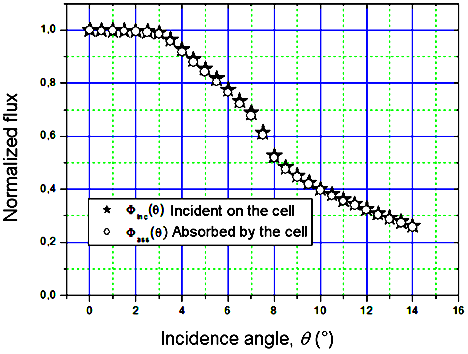

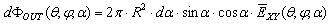

obtained irradiating the Rondine Gen1 by DCM is shown in Fig. 50. As we are interested to study the distribution of output flux as function of only the polar angle α, we transform the irradiance EXY (θ, φ, α, β) in the β-symmetrized function

obtained irradiating the Rondine Gen1 by DCM is shown in Fig. 50. As we are interested to study the distribution of output flux as function of only the polar angle α, we transform the irradiance EXY (θ, φ, α, β) in the β-symmetrized function  by setting the rotational symmetry. Fig. 51 shows an example of rotational map

by setting the rotational symmetry. Fig. 51 shows an example of rotational map  and the corresponding radial profile. The radial profile of Fig. 51b is plotted as function of r, distance of the projected point on the screen from the optical axis; then we have: sinα = r / R, with R screen radius.

and the corresponding radial profile. The radial profile of Fig. 51b is plotted as function of r, distance of the projected point on the screen from the optical axis; then we have: sinα = r / R, with R screen radius. | Figure 50. Rondine Gen1 3D map of the irradiance  produced on the internal surface of the hemispherical screen produced on the internal surface of the hemispherical screen |

| Figure 51. Rondine Gen1 map of the β-symmetrized irradiance projected on the XY plane (a) and corresponding radial profile for θ=5° incidence along the y-axis (φ =90°) (b) |

corresponds to the output radiance of Rondine,

corresponds to the output radiance of Rondine,  , after β-symmetrization:

, after β-symmetrization:  . We can write therefore for the elemental flux in the α, α+dα interval:

. We can write therefore for the elemental flux in the α, α+dα interval: | (21) |

| (21) |

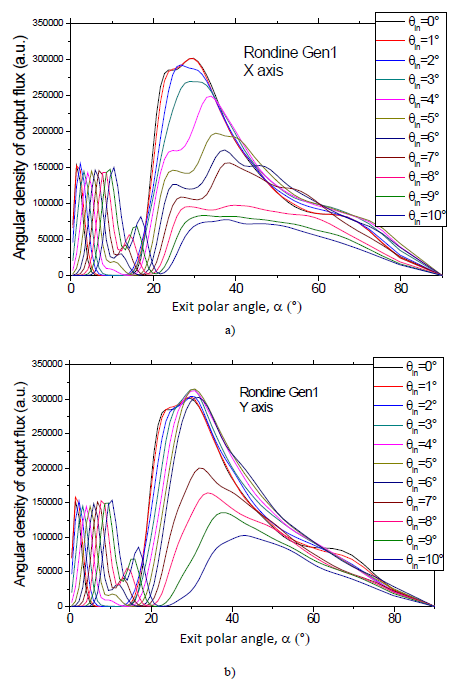

has been simulated for the Rondine Gen1 along the x-axis (φ = 0) and the y-axis (φ= 90°), for α varying in the 0°÷10°, and the results are shown in Fig. 52. Figs. 52a and 52b show that, apart from a minor peak near 0°, in the Rondine Gen1 most of the outgoing flux has a divergence between about 20° and 80°, with a large peak at around 30° which tends to move to the right at increasing the input incidence angle.

has been simulated for the Rondine Gen1 along the x-axis (φ = 0) and the y-axis (φ= 90°), for α varying in the 0°÷10°, and the results are shown in Fig. 52. Figs. 52a and 52b show that, apart from a minor peak near 0°, in the Rondine Gen1 most of the outgoing flux has a divergence between about 20° and 80°, with a large peak at around 30° which tends to move to the right at increasing the input incidence angle. | Figure 52. Angular density distribution of the output flux transmitted by the Rondine Gen1 (+box) as function of ten incidence polar angles of the parallel beam at input: θin = 0.0°-10.0° with steps of 1.0°. (a) The beam is oriented towards the x-axis (φ =0°). (b) The beam is oriented towards the y-axis (φ =90°) |

| Figure 53. Angular density distribution of the output flux transmitted by the Rondine Gen2 (+box) as function of ten incidence polar angles of the parallel beam at input: θin = 0.0°-10.0° with steps of 1.0° |

6. Conclusions

- We have described two methods for the optical analysis of light concentrators with a detailed characterization of two specific nonimaging concentrators already employed in low concentration photovoltaic module. The first presented technique is a conventional “direct” method (DCM) which simulates the direct solar irradiation; the second one is the recently developed “inverse” method (ILM) where the concentrator is reversely used as illuminator, applying a proper extended light source at the exit aperture of the concentrator. We have demonstrated the equivalence between the two methods to get the angle-resolved optical efficiency of the optics by experimental and simulated measurements. We have also demonstrated that ILM is significantly more advantageous than DCM when dealing with small size concentrators, in terms of handiness and operating speed. Besides the measurements of optical transmission efficiency, we report the results of simulations for other relevant parameters characterizing the optics: the average number of the light-rays’ reflections on the reflective wall of the concentrator under test; the spatial flux distribution on the receiver; the angular distribution of light at the output of the concentrator. Analysing these results, we can conclude that the “Rondine®” light concentrators here evaluated show optical properties appropriate for CPV applications. In particular, the following points are particularly relevant: high optical efficiency when the concentrator is well aligned toward the Sun; high acceptance angles, which allow the use of these concentrators on two-axis PV solar trackers with pointing accuracy within ±4°; absence of hot-spots on the receiver, thanks to an adequate spatial and angular distribution of the light flux at the output of the concentrator.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- We acknowledge with gratitude the help provided by dott. Mauro Campa during the experimental measurements on the Rondine.

Appendix

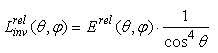

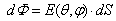

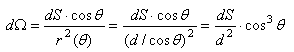

- When the inverse method is simulated, the planar screen is configured as an ideal absorber and the profile of the measured incident irradiance

(see Fig. A1a) is converted into the profile of the radiance distribution function of the concentrator,

(see Fig. A1a) is converted into the profile of the radiance distribution function of the concentrator,  , by the (cosθ)-4 factor. Indeed, if

, by the (cosθ)-4 factor. Indeed, if  is a point on the screen,

is a point on the screen,  the corresponding incident irradiance and dS an elementary area around

the corresponding incident irradiance and dS an elementary area around  , the flux through area dS is

, the flux through area dS is  and it is confined within the solid angle

and it is confined within the solid angle  given by:

given by: | (A1) |

direction will be therefore expressed by:

direction will be therefore expressed by: | (A2) |

| (A3) |

| (A4) |

| (A5) |

| Figure A1. (a) Schematic of the irradiation of the planar screen (ps) by the inverse light produced by the solar concentrator (sc). (b) Process of recording by the CCD of the image produced by the irradiance map produced on the planar screen.  is a point on the screen and is a point on the screen and  is the corresponding incident irradiance. (c) The CCD is schematised as a lens and a plane representing the image sensor of the CCD; is the corresponding incident irradiance. (c) The CCD is schematised as a lens and a plane representing the image sensor of the CCD;  is a point and is a point and  is the intensity (irradiance) on the CCD sensor is the intensity (irradiance) on the CCD sensor |

is:

is: | (A6) |

is the reflected irradiance, and

is the reflected irradiance, and  is the radiance of the screen. The flux reflected by the unitary area of (ps) and flowing inside the solid angle by which the unitary area is seen by point

is the radiance of the screen. The flux reflected by the unitary area of (ps) and flowing inside the solid angle by which the unitary area is seen by point  is:

is: | (A7) |

. The intensity of the CCD image at point

. The intensity of the CCD image at point  , proportional to the irradiance incident at that point, is therefore:

, proportional to the irradiance incident at that point, is therefore: | (A8) |

| (A9) |

| (A10) |

| (A11) |

| (A12) |

References

| [1] | D. Fontani , P. Sansoni, E. Sani, S. Coraggia, D. Jafrancesco, L. Mercatelli, “Solar divergence collimators for optical characterisation of solar components”, Int. J. of Photoenergy, Volume 2013, Article ID 610173-1, 10 pages. |

| [2] | P. Sansoni, D. Fontani, F. Francini, A. Giannuzzi, E. Sani, L. Mercatelli, D. Jafrancesco, “Optical collection efficiency and orientation of a solar trough medium-power plant installed in Italy”, Renewable Energy, 36 (2011) 2341-2347. |

| [3] | F. Francini, D. Fontani, P. Sansoni, L. Mercatelli, D. Jafrancesco, E. Sani, “Evaluation of Surface Slope Irregularity in Linear Parabolic Solar Collectors”, Int. J. of Photoenergy, Volume 2012, Article ID 921780-1, 6 pages. |

| [4] | D. Jafrancesco, E. Sani, D. Fontani, L. Mercatelli, P. Sansoni, A. Giannini, F. Francini, “Simple methods to approximate CPC shape to preserve collection efficiency”, Int. J. of Photoenergy, Volume 2012, Article ID 863654-1, 7 pages. |

| [5] | P. Sansoni, F. Francini, D. Fontani, “Optical characterisation of solar concentrator”, Optics and Lasers in Engineering, 45 (2007) 351-359. |

| [6] | A. Parretta, “Optics of solar concentrators Part I: Theoretical models of light collection”, Int. J. of Optics and Applications, 3 (2013) 27-39. |

| [7] | A. Parretta and A. Antonini, “Optics of Solar Concentrators. Part II: Models of Light Collection of 3D-CPCs under Direct and Collimated Beams”, Int. J. of Optics and Applications, 3 (2013) 72-102. |

| [8] | A. Parretta, A. Antonini, M. Butturi, P. Zurru, "Optical simulation of Rondine® solar concentrators by two inverse characterization methods", Journal of Optics, 14 (2012) 125704 (8pp). |

| [9] | A. Parretta, A. Antonini, M. Butturi, E. Milan, P. Di Benedetto, D. Uderzo, P. Zurru, “Optical Methods for Indoor Characterization of Small-Size Solar Concentrators Prototypes", Advances in Science and Technology, Vol. 74 (2010) pp. 196-204. Trans Tech Publications, Switzerland. |

| [10] | A. Parretta, A. Antonini, E. Bonfiglioli, M. Campa, D. Vincenti, G. Martinelli, “Il metodo inverso svela le proprietà dei concentratori solari”, PV Technology, n. 3, Agosto/Settembre 2009, pag. 58-64. |

| [11] | A. Parretta, A. Antonini, E. Milan, M. Stefancich, G. Martinelli, M. Armani, "Optical efficiency of solar concentrators by a reverse optical path method", Optics Letters, 33 (2008) 2044-2046. |

| [12] | A. Parretta, F. Aldegheri, D. Roncati, C. Cancro, R. Fucci, "Optical Efficiency of "PhoCUS" C-Module Concentrators", Proc. of the 26th EPSEC, Hamburg, Germany, 5-9 September 2011. |

| [13] | A. Parretta, L. Zampierolo, A. Antonini, E. Milan, D. Roncati, "Theory of "Inverse Method" Applied to Characterization of Solar Concentrators", 25th European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference, Feria Valencia, 6-10 September 2010, Valencia, Spain. |

| [14] | A. Parretta, L. Zampierolo, G. Martinelli, A. Antonini, E. Milan, C. Privato, "Methods of Characterization of Solar Concentrators", 25th European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference, Feria Valencia, 6-10 September 2010, Valencia, Spain. |

| [15] | A. Parretta, D. Roncati, "Theory of the "Inverse Method" for Characterization of Solar Concentrators", “Optics for Solar Energy (SOLAR)", Advancing the Science and Technology of Light, The Westin La Paloma, Tucson, AZ, USA, June 7-10, 2010. |

| [16] | A. Parretta, G. Martinelli, A. Antonini, D. Vincenzi, "Direct and inverse methods of characterization of solar concentrators", "Optics for Solar Energy (SOLAR)", Advancing the Science and Technology of Light, The Westin La Paloma, Tucson, AZ, USA, June 7-10, 2010. |

| [17] | A. Parretta, L. Zampierolo, D. Roncati, "Theoretical aspects of light collection in solar concentrators ", "Optics for Solar Energy (SOLAR)", Advancing the Science and Technology of Light, The Westin La Paloma, Tucson, AZ, USA, June 7-10, 2010. |

| [18] | A. Parretta, A. Antonini, M.A. Butturi, P. Di Benedetto, E. Milan, M. Stefancich, D. Uderzo, P. Zurru, D. Roncati, G. Martinelli, M. Armani, “How to "Display" the Angle-Resolved Transmission Efficiency of a Solar Concentrator Reversing the Light Path", 23rd EPVSEC, 1-5 September 2008, Feria Valencia, Valencia, Spain. |

| [19] | A. Parretta, A. Antonini, M. Stefancich, G. Martinelli, M. Armani, “Optical Characterization of CPC Concentrator by an Inverse Illumination Method”, 22nd EPVSEC, Fiera Milano, 3–7 September 2007, Milan. |

| [20] | A. Parretta, A. Antonini, M. Stefancich, V. Franceschini, G. Martinelli, M. Armani, “Laser Characterization of 3D-CPC Solar Concentrators”, 22nd EPVSEC, Fiera Milano, 3–7 September 2007, Milan. |

| [21] | A. Parretta, A. Antonini, M. Stefancich, G. Martinelli, M. Armani, “Inverse illumination method for characterization of CPC concentrators”, SPIE Optics and Photonics Conference, San Diego, California (USA), 26-30 August 2007. Optical Modeling and Measurements for Solar Energy Systems, ed. by Daryl R. Myers, Proc. of SPIE Vol. 6652, 665205, (2007). |

| [22] | A. Parretta, A. Antonini, M. Stefancich, V. Franceschini, G. Martinelli, M. Armani, “Characterization of CPC solar concentrators by a laser method”, SPIE Optics and Photonics Conference, San Diego, California (USA), 26-30 August 2007. Optical Modeling and Measurements for Solar Energy Systems, edited by Daryl R. Myers, Proc. of SPIE Vol. 6652, 665207, (2007). |

| [23] | M. Stefancich, A. Antonini, E. Milan, G. Martinelli, M. Butturi, P. Zurru, P. Di Benedetto, D. Uderzo, A. Parretta, “Optical Tailoring of Flat Faceted Collector for Optimal Flux Distribution on CPC Receiver”, Int. Conference on Solar Concentrators for the Generation of Electricity or Hydrogen, ICSC-4, March 12-16 2007, El Escorial, Spain. |

| [24] | E. Bonfiglioli, “Sviluppo di metodi per la caratterizzazione ottica indoor di concentratori solari”, Tesi di Laurea in Fisica ed Astrofisica, Università degli Studi di Ferrara, A. A. 2007-2008, Ferrara, Italy. |

| [25] | A. Antonini, M.A. Butturi, P. Di Benedetto, D. Uderzo, P. Zurru, E. Milan, M. Stefancich, M. Armani, A. Parretta, N. Baggio, “Rondine® PV Concentrators: Field Results and Developments”, Progress in Photovoltaics 17 (2009) 451-9. |

| [26] | A. Antonini, M.A. Butturi, P. Di Benedetto, D. Uderzo, P. Zurru, E. Milan, M. Stefancich, A. Parretta, N. Baggio, "Rondine PV Concentrators: Field Results and Innovations", 24th EPVSEC, Hamburg, Germany, 21-25 September 2009. |

| [27] | A. Antonini, M.A. Butturi, P. Di Benedetto, D. Uderzo, P. Zurru, E. Milan, A. Parretta, N. Baggio, "Rondine PV Concentrators: Field Results and Progresses", 34th IEEE PVSC, Philadelphia, US, 7-12 June 2009. |

| [28] | A. Antonini, M.A. Butturi, P. Di Benedetto, E. Milan, D. Uderzo, P. Zurru, M. Stefancich, A. Parretta, M. Armani, N. Baggio, "Field testing per la tecnologia di concentratori a disco e per moduli “Rondine”", Proc. of “ZeroEmission Rome 2008”, Rome, Italy, 1-4 October 2008. |

| [29] | A. Antonini, M.A. Butturi, P. Di Benedetto, D. Uderzo, P. Zurru, E. Milan, M. Stefancich, M. Armani, A. Parretta, N. Baggio, “Development of "Rondine" Concentrating PV Module - Field Results and Progresses”, 23rd EPVSEC, 1-5 September 2008, Valencia, Spain. |

| [30] | A. Antonini, M. Stefancich, P.Zurru, M. Butturi, P. Di Benedetto, D. Uderzo, E. Milan, G. Martinelli, M. Armani, A. Parretta, N. Baggio, L. Secco, “Experimental Results of a New PV Concentrator System for Silicon Solar Cells”, 22nd EPVSEC, 3–7 September 2007, Milan, Italy. |

| [31] | J. Chaves, Introduction to Nonimaging Optics, 2008 (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, (London: Taylor and Francis)). |

| [32] | J.J. O’Gallagher, Nonimaging Optics in Solar Energy, 2008 (Morgan & Claypool Publishers, Lexington, KY). |

| [33] | R. Winston, J.C. Miñano, P. Benítez, 2005, Nonimaging Optics (Amsterdam: Elsevier, (New York: Academic)). |

| [34] | W.T. Welford and R. Winston, 1989, High Collection Nonimaging Optics (San Diego, CA: Academic). |

| [35] | A. Luque, 1989, Solar Cells and Optics for Photovoltaic Concentration, Adam Hilger, Bristol and Philadelphia. |

| [36] | W.T. Welford and R. Winston, 1978, The Optics of Nonimaging Concentrators, Light and Solar Energy, Academic Press. |

| [37] | R. Winston, Principles of Solar Concentrators of a Novel Design, Solar Energy, 16 (1974) 89-95. |

| [38] | A. Antonini, M. Stefancich, J.Coventry, A. Parretta, “Modelling of compound parabolic concentrators for photovoltaic applications”, Int. Journal of Optics and Applications, 3 (2013) 40-52. |

| [39] | A. Parretta, G. Martinelli, M. Stefancich, D. Vincenzi and R. Winston, “Modelling of CPC-based photovoltaic concentrator”, Proc. of SPIE, Vol. 4829, 2003, pp. 1045-1047. |

| [40] | Wilbert, B. Reinhardt, J. DeVore, M. Röger, R. Pitz-Paal, C. Gueymard, R. Buras, “Measurement of Solar Radiance Profiles With the Sun and Aureole Measurement System”, J. of Solar Energy Engineering, 135 (2013) 041002 1-11. |

| [41] | F. Grum and G. W. Luckey, “Optical Sphere Paint and a Working Standard of Reflectance”, Applied Optics, 7 (1968) 2289-2294. |

| [42] | MARCON Costruzioni Ottico Meccaniche, Via Isonzo 4, 30027 San Donà di Piave (VE), Italy.http://www.marcontelescopes.com/prodotti/ottica.php |

| [43] | A. Parretta and G. Calabrese, "About the Definition of "Multiplier" of an Integrating Sphere", Int. J. of Optics and Applications, 3 (2013) 119-124. |

| [44] | A. Parretta, H. Yakubu, F. Ferrazza, P.P. Altermatt, M.A. Green and J. Zhao, “Optical Loss of Photovoltaic Modules under Diffuse Light”, Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, 75 (2003) 497-505. |

| [45] | A. Parretta, P.P. Altermatt and J. Zhao, “Transmittance from Photovoltaic Materials under Diffuse Light”, Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, 75 (2003) 387-395. |

| [46] | P. Maddalena, A. Parretta, A. Sarno and P. Tortora, “Novel Techniques for the Optical Characterization of Photovoltaic Materials and Devices”, Optics and Lasers in Engineering, 39 (2003). |

| [47] | A. Parretta, H. Yakubu, F. Ferrazza, “Method for Measurement of the Hemispherical/Hemispherical Reflectance of Photovoltaic Devices”, Optics Communications, 194 (2001) 17-32. |

| [48] | A. Parretta, C. Privato, G. Nenna, A. Antonini, M. Stefancich, “Monitoring of concentrated radiation beam for photovoltaic and thermal solar energy conversion applications”, Applied Optics, 45 (2006) 7885-7897. |

| [49] | A. Parretta, A. Antonini, M. Stefancich, "Codice di calcolo "LS-CCD" per l'analisi dell'immagine prodotta intercettando un fascio di luce con un diffusore", SIAE, Registro Pubblico Speciale per i Programmi per Elaboratore, Numero progressivo 007144, Ordinativo D006364, 15 Aprile 2009. |

| [50] | D. Vincenzi, M. Stefancich, S. Baricordi, C. Malagù, M. Pasquini, F. Gualdi, G. Martinelli, A. Parretta, A. Antonini, “ffects of irradiance distribution unevenness on the ohmic losses of point-focus and dense-array CPV systems”, 24th EPVSEC, Hamburg, Germany, 21-25 September 2009. |

| [51] | E. Franklin, J. Coventry, “Effects of Highly Non-uniform Illumination Distribution on Electrical Performance of Solar Cells”, ANZSES Solar Conference, 2002, Newcastle, Australia. |

| [52] | A. Antonini, M. Stefancich, D. Vincenzi, C. Malagà, F. Bizzi, A. Ronzoni, G. Martinelli, “Contact grid optimization methodology for front contact concentration solar cells”, Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, 80 (2003) 155-166. |

| [53] | R. Leutz, A. Suzuki, A. Akisawa, T. Kashiwagi, “Flux uniformity and spectral reproduction in solar concentrators using secondary optics”, ISES Solar World Congress, Adelaide, 2001. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML

. Here it is shown the typical efficiency curve of a solar concentrator based on the nonimaging optics (NIO). The efficiency curve contains the relevant information of the acceptance angle, the angle at which the efficiency drops to the 50% of the maximum value (to the 90% of the maximum value for PV applications)

. Here it is shown the typical efficiency curve of a solar concentrator based on the nonimaging optics (NIO). The efficiency curve contains the relevant information of the acceptance angle, the angle at which the efficiency drops to the 50% of the maximum value (to the 90% of the maximum value for PV applications)