-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Prevention and Treatment

p-ISSN: 2167-728X e-ISSN: 2167-7298

2015; 4(2A): 1-10

doi:10.5923/s.ijpt.201501.01

Mild Cognitive Impairment and Driving Habits

Ioanna Katsouri 1, Loukas Athanasiadis 2, Evangelos Bekiaris 3, Katerina Touliou 3, Magda Tsolaki 4

1Department of Occupational Therapy, Technological Educational Institution (TEI) of Athens, Athens, Greece

21st Department of Psychiatry, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

3Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Hellenic Institute of Transport, Athens, Greece

43rd Department of Neurology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

Correspondence to: Magda Tsolaki , 3rd Department of Neurology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction: In everyday clinical practice physicians, psychologists and occupational therapists often discuss with patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) about safe driving. They try also to determine the ability of a person with Cognitive Impairment to drive. The aim of this study was to examine the behaviour of elder drivers with MCI compared with healthy elderly and define their differences in driving habits. Methods: We identified consecutive 60 participants, 44 patients with MCI and 16 Healthy Controls. All the participants were assessed with a neuropsychological battery: Mini Mental State Examination-MMSE, Clock-drawing Test, Functional Rating Scale of Symptoms of Dementia (FRSSD) scores and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and a driving questionnaire containing 33 questions with 52 sub-questions. Results: The 92.3% of patients with MCI renewed their driving licence compared to 60% of normal subjects (χ2(1)=4.403, p=0.036). Considering only those participants who still drive, normal subjects drive more kilometres per month than patients with MCI (χ2(5)=12.767, (p=0.026). Conclusions: Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment realize their difficulty in driving and drive fewer miles, however, they renew their license for fear of losing this ability.

Keywords: Mild cognitive impairment, Driving, Elderly, Occupational therapy

Cite this paper: Ioanna Katsouri , Loukas Athanasiadis , Evangelos Bekiaris , Katerina Touliou , Magda Tsolaki , Mild Cognitive Impairment and Driving Habits, International Journal of Prevention and Treatment, Vol. 4 No. 2A, 2015, pp. 1-10. doi: 10.5923/s.ijpt.201501.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- As population ages the number of older drivers on the road will continue to increase and the incidence of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) will also grow. There are only few studies which have investigated the impact of MCI on driving ability, and they have used different methods to define MCI and to examine the driving ability. There is currently very little consensus on what test batteries may be helpful in determining driving ability. The above issues present a problem in generalising the findings, and due to the shortage of available data, the picture that has emerged is, so far, inconclusive, as to whether people with MCI diagnosis are safe to drive [1]. The results of others studies suggest that medical warnings may help to prevent body lesions from road crashes. The data also suggest that incentives for physicians to offer such warnings increase their frequency. According to Donald et al [2], Physicians warnings to patients who are potentially unfit to drive may contribute to a decrease in subsequent trauma from road crashes, yet they may also exacerbate mood disorders and compromise the doctor-patient relationship. The main risk of such practices is that, taken to the extreme, they could result in a limited driving privilege for patients who might be inherently safe drivers [3].The desire and need to drive for independence and mainly the community mobility to engagement in occupations are a pressing issue for the older adults due to the age related functional changes that may interfere with driving performance and safety. For 31 million licensed drivers older than age 65 (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration) [4] and 13 million Americans older than age 15 who report a limitation in instrumental activities of daily living, clinical resources to address their community mobility needs are insufficient [5]. Several methods have been used to determine a person’s ability to drive: neuropsychological scales, driving simulators and evaluation under real driving conditions (on - road testing). Studies on the validity and reliability of these tests in the evaluation of driving ability showed mixed results.

1.1. Mild Cognitive Impairment

- There are several brief screening instruments which can adequately detect dementia. Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (aMCI) is believed to represent a transitional stage between normal healthy ageing and dementia. In particular, aMCI patients have been shown to have higher annual transition rates to Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) than individuals without cognitive impairment. Despite the big interest investigating the neuroanatomical basis of this transition, there remain a number of questions regarding the pathophysiological process underlying aMCI itself [6]. Neuropsychological batteries, neuroimaging (Magnetic Resonance Imaging-MRI), Positron Emission Tomography (PET), Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) and blood proteins levels are used as biomarkers to discriminate patients with MCI who will progress to AD or other types of dementia from MCI patients who will stay stable or return to normal ageing.A number of recent studies in aMCI have also shown specific impairment in connectivity within the default mode network (DMN), which is a group of brain regions strongly related to episodic memory capacities. However to date, no study has investigated the integrity of the DMN between patients with aMCI and those with a non-amnestic pattern of MCI (naMCI) [7]. So although there are many AD biomarkers until today, we cannot discriminate yet easily patients with aMCI from patients with other kinds of MCI and patients with MCI who will progress to AD in certain time.

1.2. Driving in Older Adults

- Driving and community mobility are identified as Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) [8] in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework. Driving is a dimension within the functional spectrum of mobility [9]. Community mobility is defined as “moving around in the community and using public or private transportation, such as driving, walking, bicycling, or accessing and riding in buses, taxi cabs, or other transportation systems” [10]. For many people with medical impairment, driving remains the most appreciated IADL once basic needs regarding their activity of daily living are fulfilled [11] Occupational therapy practitioners must use their clinical judgment to evaluate driving as an IADL and address clients’ community mobility. This judgment may be based on observation of ADL and IADL performance or on results from an evaluation using evidence-based tools, and it may result in recommendations for interventions to promote mobility or an appropriate pathway for referral [12].Both driving and community mobility provide the opportunity for people to participate in education, work, leisure, social participation, and other IADLs. The overwhelming preference for driving is expected in an auto mobile dependent society such as the United States, in which daily occupations are often dependent on the ability to drive [13]. Access to a private vehicle, either as a driver or as a passenger, affords considerable independence for seniors when completing their daily activities. Driving an automobile in older adulthood is associated with prolonged health and independence [14]. With the growing number of older people living in society, safe transportation for seniors is becoming a global issue and must include a focus on both drivers and passengers [15]. There are opportunities for occupational therapists to address older driver safety within both medical and social models of health. Occupational therapists should develop community transition groups to help drivers plan for a successful driving retirement [16]. The evidence for interventions focusing on the older driver was grouped under the following themes: educational interventions, interventions addressing cognitive-perceptual skills, interventions addressing physical fitness, simulator training to address driving skills, and behind-the- wheel training to address driving skills [17]. The presence and role of occupational therapy should increase in USA- Australia and local policy making agencies and in transportation companies to facilitate attention to older adult participation through engagement in community mobility [18]. In the future it seems necessary for OTs in Sweden to undergo specialized training and perform the assessments on a regular basis to maintain a high level of competence as driving assessors [19].

1.3. Driving Assessment in People with AD and MCI

- So far the effect of screening for AD and cognitive impairment on patient, caregiver, or clinician decision making or societal outcomes in correlation with driving has not been examined.The Occupational therapy assessment of people with AD aims to identify the remaining skills, to assess the environmental factors and determine the individual's interests. In the early stages of cognitive decline our interest focuses on safety. In this field, assess the ability of moving with orientation, the use of objects for the purpose for which they are intended and individual problems that affect safety [20]. Patients with MCI may present minor impairment in IADL, [21] more demanding in terms of cognitive function, such as shopping, handling money, cooking, housekeeping and using the telephone. However, persons with MCI have subtle changes in IADLs and participation that can decrease quality of life, can increase quality of life, can increase safety risk, and may be predictive of continued functional decline [22]. To determine the ability of someone with dementia to drive several methods have been used: neuropsychological scales, driving simulators and evaluation under real driving conditions (on - road testing), with mixed results regarding their validity and reliability [23] [24]. There are few methods to underline driving risks in patients with early dementia and MCI. It is well known that structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI) of the hippocampus—a biomarker of probable AD and a measure of disease severity in those affected - is linked to objective ratings of on-road driving performance in older adults with and without aMCI. Another study appears warranted to better discern patterns of brain atrophy in MCI and AD and whether these could be early markers of clinically meaningful driving risk. Mild atrophy of the left hippocampus was associated with less-than-optimal ratings in lane control but not with other discrete driving skills. Decrements in left hippocampus volume conferred higher risk for less-than-optimal lane control ratings in the patients with MCI. These findings suggest that there may be a link between hippocampus atrophy and difficulties with lane control in persons with amnesic MCI. Further study appears warranted to better discern patterns of brain atrophy in MCI and Alzheimer’s disease and whether these could be early markers of clinically meaningful driving risk [25]. But sMRI is an expensive examination. However assessing a person’s fitness to drive when they have cognitive impairment is problematic [1]. Drivers with cognitive impairment referred for a driving assessment were accurately categorised as unsafe, safe, or in need of further testing, by using DriveSafe and DriveAware, with only 50% needing an on-road assessment. Further research is required to replicate these findings [26]. Drive Safe is a measure of awareness of the driving environment, and DriveAware is a measure of awareness of driving ability. Driving performance was assessed using these two tools, then via standardised on-road assessment within one week. Outcomes of on road testing were based on agreement between the occupational therapist and driving instructor, and categorised as either: pass, conditional pass (restrictions on license, for example automatic vehicle only), downgrade to a learner’s permit, or fail [27]. Thousands of older drivers present themselves, or are reported to licensing authorities annually as being potentially unfit-to-drive and requiring testing. Occupational therapists are asked by the licensing authorities in USA/North Europe to report off- and on-road assessment findings to be used in fitness-to-drive decisions. Whereas there are many standardised assessments of cognition⁄sensation that are predictive of driving performance, at present there is neither a consistent nor an agreed and accepted worldwide approach to use these assessments nor reporting their findings to licensing authorities. This means that the assessment experience can vary for the client and licensing decisions may not be based on the best evidence. Furthermore, the competency standards for driver assessment that are widely used require the inclusion of physical, sensory and cognitive components in a comprehensive off-road assessment. Today there are very few low-cost, face-valid, off-road assessment batteries available today. The Occupational Therapy-Driver Off Road Assessment (OT-DORA) Battery [28] and The Occupational Therapy Home Maze Test (OT-DHMT) which is part of the OT- DORA Battery and used in licensing recommendations for older and/or functionally impaired drivers. Previously published research has been conducted to investigate the predictive validity, inter-rater reliability and establish norms for this timed test with normal and cognitively impaired drivers. The validity of the test further supported when it was found that there was no statistically significant difference between time taken to complete the test for right and left handed people aged 18-69, t(33)=1.59, p=0.12 (95%CI: - 0.63 to 5.08) [29]. However, some functional deficits do not necessarily preclude driving and Occupational Therapy Driver Assessors (OTDAs) play an important role in maintaining and promoting the driving independence of individuals with activity limitations or participation restrictions [30] [31].Specialist Occupational Therapy Driver Assessors and driver licensing authorities require on-road assessment procedures that are both valid and reliable. Assessment validity may be influenced by both test route characteristics and driver characteristics [32]. The existing international guidelines, which recommend specialised on-road testing when driving safety is doubtful for patients with MCI, highlight the importance of assessing executive dysfunction and caregiver concern about driving [33]. Driving simulators provide another avenue to evaluate the driving capacity of older adults. They also enable evaluation of driving skills in a highly standardized fashion that on road evaluations cannot achieve. Driving simulators are now affordable and may also be more cost-effective and time efficient than on-road driving evaluations [34]. The specific performance measures included; approach speed, number of brake applications on approach to the intersection (either excessive or minimal), failure to comply with stop signs, and slower braking response times on approach to a critical light change. Evidence from driving simulator and on-road driving studies provide a basis for understanding which driving behaviours may be compromised in MCI patients. Driving simulators allow for assessment of response to road hazards in a safe and controlled environment [35]. In Greece we have a simulator too at the Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Hellenic Institute of Transport in Thessaloniki and we have done pilot measurements with our sample.

2. Method

- Participants were outpatients of the Memory and Dementia Outpatient Clinic of the 3rd Department of Neurology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, with cognitive complaints. Participants were diagnosed with MCI according to Petersen and Winblad criteria, by a group of specialized health professionals. Neurological examination, neuropsychological and neuropsychiatric assessment, medical/social history, neuroimaging examination and blood tests were performed to support the diagnosis of MCI.Two questionnaires were combined and administered to patients and a third one created by the research team. The first one was a user questionnaire AGed people Integration, mobility, safety and quality of Life Enhancement through driving (AGILE) [36] new one adjusted in patients with dementia. The basic idea of AGILE project was to allow elderly people to continue driving safely as long as possible, because driving as individualistic transport mode has become quasi a necessity to keep up with current mobility standards. The aim of the (AGILE) [37] initiative is the development of a new set of training, information, counselling and driving ability assessment and support tools for the elderly, evaluating their full range of abilities. From the data collected, guidelines for the design of automotive human machine interfaces (HMIs) for the older drivers will be deducted.The second was “A questionnaire driving in patients with dementia” and contains 40 questions. It shows good reliability and validity (a Cronbach = .80) [38]. The new questionnaire contains 33 questions with 52 sub-questions. In particular, we asked for information about the following topics:● Personal information: Gender, age, driving license details, any vehicle-related accidents, they evaluate themselves as a good or bad driver etc. ● Opinions about age-related training and assessment: Whether they had an age-related assessment already, what they think about age-related assessment in general, whether they are willing to retrain they driving skills, how such testing should be carried out etc. ● Physical & mental fitness: questions concerning moving parts of the body, vision, auditory perception, vascular problems, attention, memory etc.● Driving habits: which kind of traffic situations they are trying to avoid, and how they compare their driving style today to the times when they were 45 years old.One hundred twenty seven people were examined for their ability to drive at 3rd Department of Neurology at “G.Papanikolaou” General Hospital of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki between December 2012 and July 2014. We identified consecutive sixty participants, 44 patients who had MCI and 16 Healthy Controls and we excluded participants with other diagnosis as MCI due to Depression, AD, Depression, etc. All the participants were examined with a neuropsychological battery: Mini Mental State Examination-MMSE [39] [40], Clock- drawing Test [41], Functional Rating Scale of Symptoms of Dementia (FRSSD) [42] and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) [43]. Healthy Controls were examined too with the same neuropsychological battery.Screening tools such as MMSE, have been used extensively in driving research studies to discriminate MCI from dementia in collaboration with Criteria for MCI and Dementia. Some studies have shown the MMSE is correlated with driving performance, while few studies have shown the predictive validity of the MMSE in determining on-road performance [44]. We used the MMSE (maximum score = 30, with scores <24 indicative of dementia) as an indicator of baseline cognitive functioning [41]. The strongest predictor of decision to report was the combination of caregiver concern about the patient's driving and abnormal Clock Drawing Test, which accounted for 62% of the variance in decision to report at the same time as or without a road test (p <0.01) [33].

3. Statistics

- Data analysis included descriptive statistics and univariate analysis. The Shapiro-Wilk test for normality was used to assess the normality assumption for continuous variables. The chi-squared test was used to test for independence between categorical variables. Comparisons of location parameters between two independent groups were conducted using the independent samples t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test depending on the normality assumption. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. SPSS 21.0 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY) was used for statistical analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Personal Information

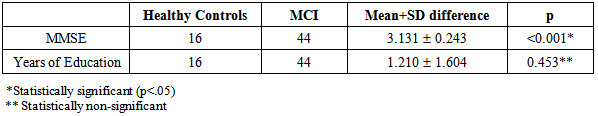

- The demographic characteristics are as follows: 60 participants, 16 (26.7%) Healthy Controls and 44 (73.3%) with MCI. Our sample consists of 47 (73.4%) males and 13 (20.3%) females.Age: “<55” 7 (11.9%), “55-64” 7 (11.9%), “65-74” 16 (27.1%), “75-84” 26 (44.1%), “>=85” 3 (5.1%).Marital status: Married 39 (69.6%), divorced 1 (1.8%), single 5 (8.9%) and widowed 11 (19.6%). Retired: yes 52 (81.3%), no 7 (10.9%). Occurrence of MCI is independent of sex (p=0.981), age groups (p=0.202) and marital status (p=0.327). The mean (±sd) MMSE score of Healthy Controls is 29.31 (±0.48) while the mean for years of education is 12.94 (±4.29). The mean MMSE and mean years of education in patients with MCI is 26.18 (±1.40) and 11.73 (±5.86) respectively. There is no significant difference in years of education between healthy controls and patients with MCI (p=0.453) while there is a significant difference in MMSE between the two groups (t(58)=12.888, (p<0.001).

|

4.2. Opinions about Age-Related Training and Assessment

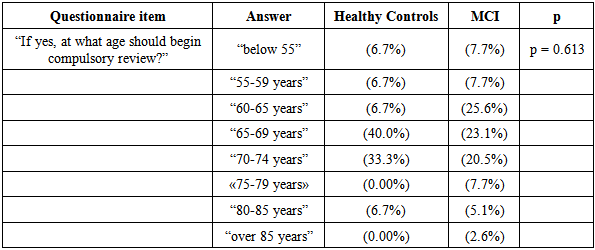

- In the question “Should there be a mandatory retesting of drivers based on age?” Healthy Controls group answered yes (100%) and MCI answers yes (90.9%), no (9.1%). There is independence between two variables (p = 0.539). The result of the question "Should there be a mandatory retesting of drivers based on age?" is independent of diagnosis. In the question “If yes, at what age should begin compulsory review?” here is independence between the two variables (p = 0.613). The effect of the question "At what age should begin compulsory review?" is independent of the diagnosis.

|

|

4.3. Physical & Mental Fitness

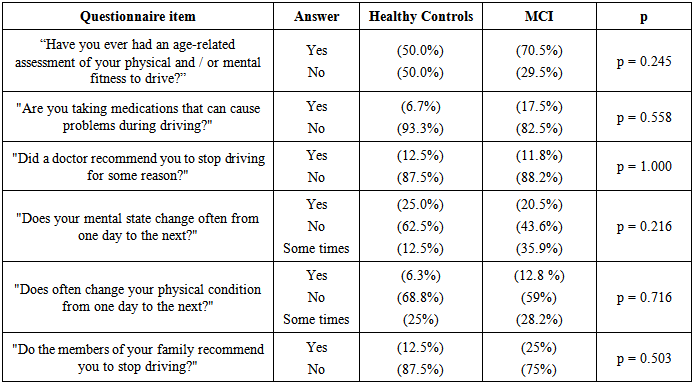

- There was no statistically significant association between the physical and mental fitness questions and diagnosis.

|

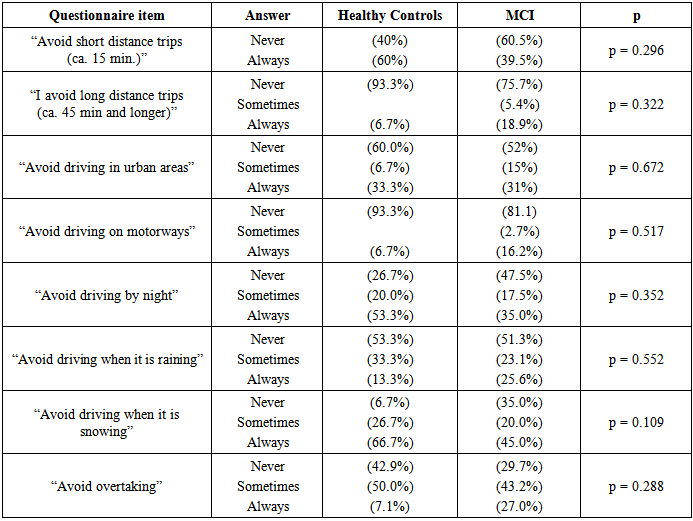

4.4. Driving Habits

- In the question "How many car accidents did you have while you were driving a car in total since you obtained your driver's license Healthy Controls answered “none” (43.8%), “1-2 times” (43.8%), “3-4 times” (12.5%) and MCI patients answered “none” (40.9%), “1-2 times” (45.5%), “3-4 times” (13.6%). There is independence between the two variables (p = 0.979). The result of the question "How many car accidents did you have while you were driving a car overall since you obtained your driver's license?" is independent of the diagnosis. Although there is a difference this difference is not significant.

|

5. Discussion

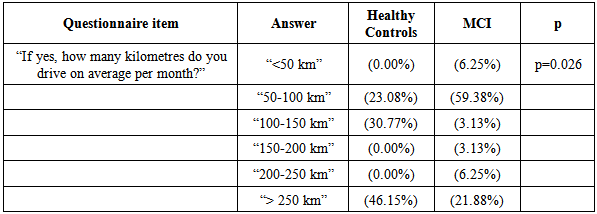

- Although equipment modifications can be made to vehicles to adapt them for drivers with physical impairment, interventions addressing cognitive and perceptual impairments are more challenging. The progressive nature of some diagnoses such as dementia may make the resulting cognitive impairment less responsive to intervention. Improvement in cognitive skills in people with dementia may not be possible, and driving rehabilitation services focus on assessing when driving cessation is required. In people with general age-related declines with more stable cognitive –perceptual performance skills of driving may improve their behind-the-wheel performance, reduce their crash risk, and prolong their driving and community mobility [45].Recent studies have examined the driving performance of individuals with MCI, as it has been hypothesized that driving may be added to the list of complex instrumental activities of daily living in which the performance of individuals with MCI is expected to be impaired [46]. Many health conditions are associated with impairment that may impact upon safe driving and crash risk [47]. Cognitively impaired older adults may be at increased risk of unsafe driving. Individuals with insight into their own impairments may minimize their risk by restricting or stopping driving. It will be important to determine, how driving practices change over time and what factors influence decisions to restrict or stop driving for people with cognitive impairment [48]. MCI refers to a stage of cognitive decline between normal ageing and very early dementia. In everyday clinical practice Occupational Therapists often have to determine the ability of a person with MCI to drive. Due to the increasing proportion of older people with cognitive deficits and the increased risk of accidents in this population, it is essential to find a reliable tool for assessing the driving capacity of this population. In our study (5.3 %) MCI patients were involved in a car accident while driving a car during the past two years and none of the Healthy Controls. According to Shaw et al [49] “safe transportation for seniors encompasses a dynamic interaction of person (driver) and environmental - related factors and a commitment by seniors to manage their driving safety”. Other findings suggest a need for more participatory research that includes seniors in the research process. Application of universal design principles to the design of vehicle safety features is suggested as a strategy that will extend their usability to people with a wider range of abilities and experiences. Opportunities for seniors to share strategies that maintain their community mobility with other seniors are also suggested as beneficial. Further research will ensure that as seniors age, they can continue to access and use safety features while driving a private vehicle. The conceptualization of the themes and issues from this study will inform the development of a national survey to further elicit seniors’ experiences and needs with regard to safe transportation. The interaction of variables related to the person and vehicle technology and the influence of this interaction on use of these devices and driving strategies should also be explored. In our research, we found that patients with MCI did worse in almost every question than Healthy Controls. Yet, 92.3% of patients with MCI renewed their driving license compared to 60% of Healthy Controls (χ2(1)=4.403, (p=0.036).The aim of our study was to describe driving behaviors of people with Mild Cognitive Impairment. All the participants were assessed with a driving questionnaire. The results describe driving habits, whether they had an age-related assessment already, what they think about age-related assessment in general, whether they are willing to retrain they driving skills, how such testing should be carried out. Which kinds of traffic situations they are trying to avoid, difficult driving conditions, like rush hours, darkness, and bad road-surface conditions etc. Similar to the Kowalski et al [48], Cognitively impaired older adults may be at increased risk of unsafe driving. Individuals with insight into their own impairments may minimize their risk by restricting or stopping driving. The purpose of this study was to examine the influence of cognitive impairment on driving status and driving habits and intentions. Participants were classified as cognitively impaired, no dementia single (CIND-single), CIND-multiple, or not cognitively impaired (NCI) and compared on their self-reported driving status, habits, and intentions to restrict or quit driving in the future. The groups differed significantly in driving status, but not in whether they restricted their driving or reduced their driving frequency. CIND-multiple group also had significantly higher intention to restrict/stop driving than the NCI group. Reasons for restricting and quitting driving were varied and many individuals reported multiple reasons, both external and internal, for their driving habits and intentions. Regardless of cognitive status, none of the current drivers were seriously thinking of restricting or quitting driving in the next 6 months. It will be important to determine, in future research, how driving practices change over time and what factors influence decisions to restrict or stop driving for people with cognitive impairment the reasons reported by participants for restricting driving or stopping driving altogether were varied. When current drivers were examined (n = 179). The cognitive groups did not differ in whether they reduced their driving frequency over the last year (χ2 (2) = 0.722, p > 0.05) or preferred not to drive in/restricted their driving to certain situations (χ2 (2) = 0.537, p > 0.05). The cognitive groups also did not differ significantly in their average number of driving restrictions (F(2, 178) = 0.422, p > .05). The older adults with CIND-single made an average of 2.36 (SD = 2.83, range = 0–9) restrictions, CIND-multiple made an average of 2.81 (SD = 2.53, range = 0–8) restrictions and the older adults with NCI made an average of 2.90 (SD = 3.10, range = 0–10) restrictions. In the literature, currently, there are a few empirical studies of driving performance and MCI, although the criterion used for defining MCI often differs between studies, and so it is difficult to say how general sable and applicable the findings may be. This has generally been interpreted as behaviour compensating eventual age-related problems in driving. However, the compensation hypothesis has also been questioned by asking whether the changes in driving habits truly reflect compensation of diminished skills in relation to travel times and weather conditions that is associated with retirement and other age-related life style changes [50]. The relatively few studies which have investigated stopping behaviour at intersections for drivers with MCI found no differences in stopping violations compared to healthy controls [35]. Future work should also examine other factors (e.g. personality) that may impact an individual’s driving habits and intentions, as well as measure insight by comparing self-report to other report and objective measures of both driving ability and abilities that might impact safe driving ability. An individual with cognitive impairment might be aware of a declining skill, but the area of impairment might have little impact on their safe driving capacity [49]. According to Donald et al [2], A total of 100,075 patients received a medical warning from a total of 6098 physicians. During the 3-year baseline interval, there were 1430 road crashes in which the patient was a driver and presented to the emergency department, as compared with 273 road crashes during the 1-year subsequent interval, representing a reduction of approximately 45% in the annual rate of crashes per 1000 patients after the warning (4.76 vs. 2.73, P<0.001). The lower rate was observed across patients with diverse characteristics. No significant change was observed in subsequent crashes in which patients were pedestrians or passengers. Medical warnings were associated with an increase in subsequent emergency department visits for depression and a decrease in return visits to the responsible physician. Previous findings that older drivers engage in strategic self-regulatory behaviours to minimize perceived safety risks are primarily based on survey reports rather than actual behaviour. Patients with (AD) displayed further restrictions of driving behaviour beyond those of healthy elderly individuals, suggesting additional regulation on the basis of cognitive status. These data provide critical empirical support for findings from previous survey studies indicating an overall reduction in driving mobility among older drivers with cognitive impairment [51]. There is evidence to suggest that those with a diagnosis of MCIor mild dementia use self-regulation to reduce their driving, e.g. not driving at night, sticking to well-known routes and avoidance of driving at peak times [52] suggesting that many are aware when driving ability starts to decline [1]. In our study considering only those patients who still drive, Healthy Controls drive more kilometers per month than patients with MCI (χ2(1)=12.767, p=0.026). Older adults with clinically-defined dementia may report reducing their driving more than cognitively normal controls. However, it is unclear how these groups compare to individuals with clinically-defined MCI in terms of driving behaviours. Thus, older adults with clinically-defined MCI, as well as those with dementia, avoided some complex driving situations more than cognitively intact adults [52].While a practical driving assessment is the golden standard, it may be difficult to compel individuals to undertake this, particularly if no overt problems are evident. The differences in MCI sub-types (amnestic vs. non-amnestic) also warrant further investigation and few studies could be found that specifically explored this area in respect to practical or real world driving skills. It could be that different subtypes of MCI have different effects on driving ability, and this could lead to the development of interventions that could delay driving cessation for a number of MCI patients [1]. Guidelines official guidance available for individuals and clinicians currently appears to offer inconsistent classifications and no clear pathway for action. According to Sommer et al [36], Demographic changes increase the need for fair and valid fitness-to-drive assessment in older drivers. In a self-report survey, 473 older drivers stratified by age (55–64, 65–74, >74 years) were asked about their driving habits, crash history, compensatory driver behaviour, and attitude towards age-based reassessment. The results showed an increase in the proportions of subjects reporting crash involvement and the subjects reporting full legal responsibility for the latest crash in older age groups. The reported use of different compensatory strategies and adaptation techniques was also higher in the older age groups. Medical fitness-to-drive screenings are not able to deal with the complexity of this paradoxical finding, because medical diagnoses do not take into account adaptation and compensation in older drivers. Age-based reassessments limited to medical screenings therefore carry an increased likelihood of false positive classifications that would unnecessarily reduce the quality of life of sufficiently safe older drivers. This risk could, however, be reduced by a client-centred approach focused on practical fitness-to-drive, providing older drivers with the opportunity to show whether they are able to cope with functional deficits in more realistic driving settings. Such an approach is in line with theoretical occupational therapy foundations.

6. Conclusions

- Since qualitative studies indicate that a particular worry for those diagnosed with a dementia is the loss of their driving license, it is reasonable to suppose that this would also be the case for those diagnosed with MCI. It is clear that this is an area that warrants further research, and that there exists a need for a defined clinical pathway and clearer legislation [1].In our research, we found that patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment realize their difficulty in driving and drive fewer miles, they renew however their license for fear of losing this ability. However, this risk could be reduced by an occupational therapy approach.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML