-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Health Science

p-ISSN: 2166-5966 e-ISSN: 2166-5990

2015; 5(3A): 14-16

doi:10.5923/s.health.201501.05

Lichen Striatus in an Adult Female

Al Ratrout JT1, Al Nazer N1, Ansari NA2

1Department of Dermatology, Qatif Central Hospital, Kingdom of Saudia Arabia

2Departments of Pathology, Bahrain Defence Force Hospital and Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland Kingdom of Bahrain

Correspondence to: Ansari NA, Departments of Pathology, Bahrain Defence Force Hospital and Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland Kingdom of Bahrain.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Lichen striatus is a not uncommon linear, self-limited skin eruption in children of unknown aetiology. It rarely affect adults, and is characterized byabrupt onset of pink, tan or hypopigmented small coalescent papules distributed in a linear configuration following Blaschko's lines usually on the extremities or around the trunk, and on the face in 10% of cases. The main differential diagnoses are lichen nitidus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN), linear morphea and lichen planus. Here we describe a case of an adult woman with itchy linear erythematous violaceous tiny papules with atrophy on the right side of the neck and face, diagnosed as lichen striatus on the basis of clinical and histopathological features. The unusual findings and diagnostic challenge are discussed.

Keywords: Lichen striatus

Cite this paper: Al Ratrout JT, Al Nazer N, Ansari NA, Lichen Striatus in an Adult Female, Journal of Health Science, Vol. 5 No. 3A, 2015, pp. 14-16. doi: 10.5923/s.health.201501.05.

1. Introduction

- Lichen striatus (LS) is an uncommon, self-limiting, linear dermatosis, which usually affects children, especially girls, between 5-15 years of age [1]. Rarer in adults, its incidence is slightly higher in women [2-4]. The cause is unknown, but it is considered by many authors as a manifestation of mosaicism, characterized by the presence of clones of genetically abnormal epithelial cells that, through a precipitating event, can be recognized by the immune system and induce the affected skin to generate an inflammatory cell mediated response [5, 6].There is an association between atopy and LS, which may contribute to its pathogenesis. Multiple studies report an increased incidence of LS in those with family history of atopy (asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis) [7], and it has also been suggested that the altered immune status of these patients might act as a predisposing factor to trigger the process. Trauma, pregnancy and drugs are also reported as precipitating factors [8, 9]. The diagnosis is essentially clinical in children but can be difficult in adults because of its rarity, so histopathological confirmation is needed especially in unusual sites such as the face.Here we report a female with 6 months history of severe itchy rash on the chin immediately after delivery. Histopathology confirmed the clinical diagnosis of lichen striatus.

2. Case Report

- A 38 year old female presented with 6 months history of itchy tiny erythematous papules over the chin extending to the right side of the neck in linear arrangement, becoming flatter with atrophy with progression (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Atrophied erythematous papules over the chin extending to the right side of the neck in linear arrangement |

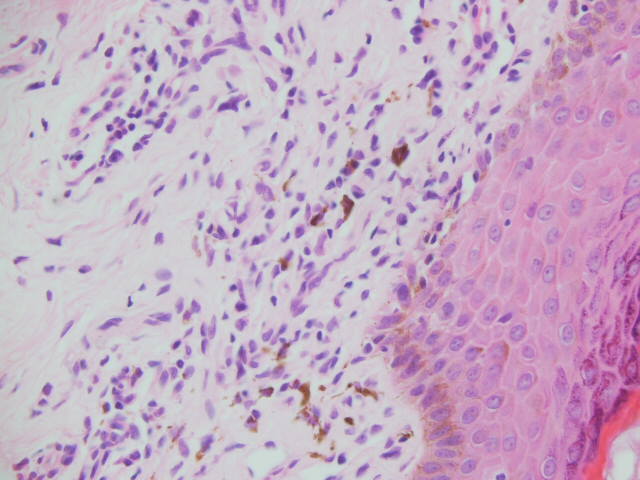

| Figure 2. Lichenoid (interface) inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes, some lymphocytes are within the basal epidermis (H&E, x400) |

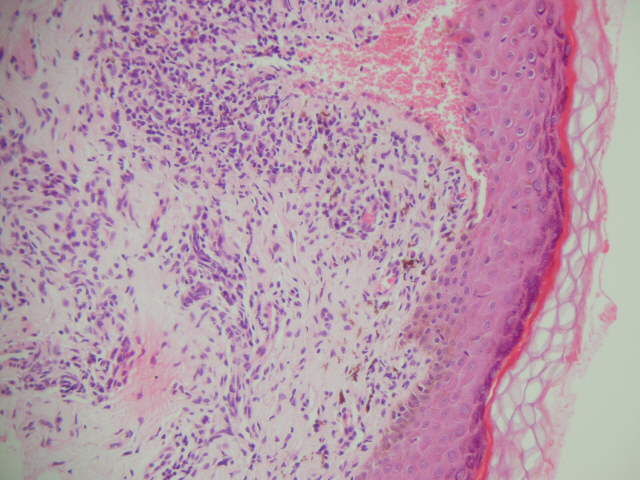

| Figure 3. Basal epidermal damage has led to focal subepidermal cleft. A deep component to the inflammatory infiltrate can also be seen (H&E, x200) |

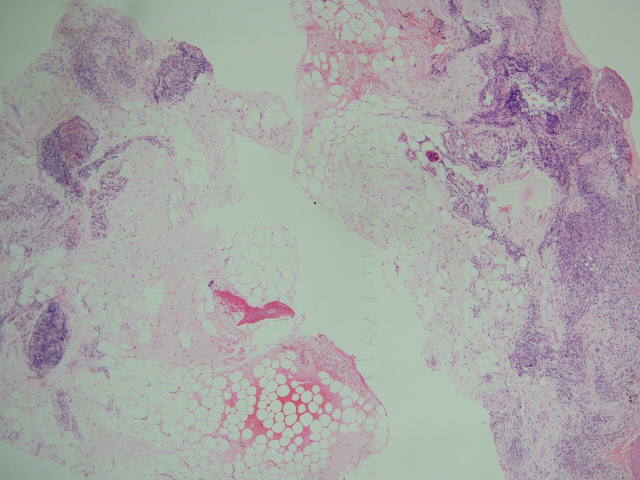

| Figure 4. Scanning power of skin biopsy reveals the lobular arrangement of inflammatory cells at the deep aspect – corresponding to perieccrine involvement – a good clue at low power (H&E, x25) |

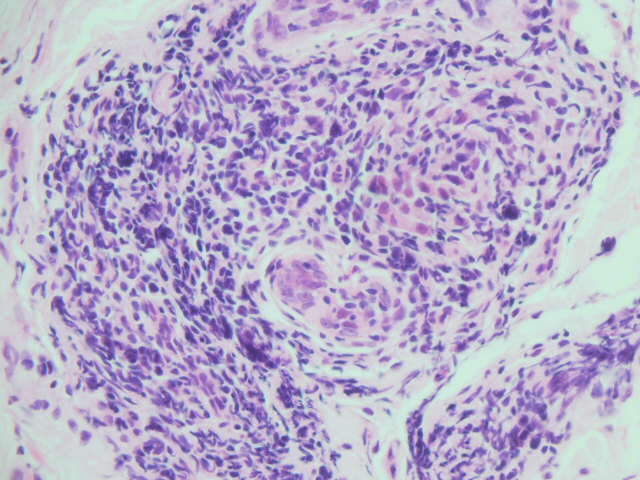

| Figure 5. Accentuation of inflammatory infiltrate around eccrine glands (H&E, x400) |

3. Discussion

- Lichen striatus (LS) is a self-limiting, acquired linear inflammatory dermatosis that is seen primarily in children and is uncommon in adults. The aetiology is unknown although there is an association with personal or family history of atopy. Certain triggering factors have been identified including infections, vaccines, pregnancy (as in the case of our patient), stress, drugs, skin trauma, and contact dermatitis [2, 8, 9, 10].Lesions begin as small (1-5mm) erythematous slightly scaly papules which form an interrupted or continuous line usually on the extremity or around the trunk following Blaschko's lines. Involvement of the chest or face (present case) is unusual. LS lesions are usually asymptomatic but when occuring in adults tend to be extensive and itchy [2, 11], sometimes requiring symptomatic treatment. The usual natural course is spontaneous resolution within 12 months. Nail involvement can occur including nail plate thinning, longitudinal ridging, splitting, and nail bed hyperkeratosis.The differential diagnosis of an acquired dermatosis in linear configuration includes linear lichen planus, linear morphea, inflammatory linear verucous dermatosis, linear epidermal naevus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal naevus, linear psoriasis, linear Darier’s disease, and incontinentia pigmenti [12]. Histopathological examination is therefore required and will provide a firm diagnosis in conjunction with the clinical features. Histopathology of LS reveals a predominantly lichenoid (interface) lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with a variable (absent to significant) degree of spongiotic dermatitis in addition. There is often hyperkeratosis and focal parakeratosis. On account of the interface dermatitis and subsequent basal epidermal damage with apoptotic cells and melanin incontinence, the features may closely resemble those of lichen planus. A striking additional feature in lichen striatus is a deep component to the inflammatory infiltrate centered around the deep dermal vascular plexus and adnexae especially perieccrine gland involvement [2, 12]. This latter feature is a helpful pointer to the diagnosis, as it was in the current case. Spongiosis (intercellular epidermal oedema) is often seen in biopsies of lichen striatus, and sometimes microvesicles containing Langerhan’s cells are formed. Sometimes spongiosis predominates over lichenoid inflammation, as for example in the rare entity adult blaschkitis. Adult blaschkitis is a term introduced in 1990 by Grosshans and Marot [13] to describe an acquired inflammatory linear eruption in adults consisting of pruritic papules and vesicular eruptions along the lines of Blaschko. It is regarded as a variant of lichen striatus and, apart from the mainly spongiotic histological pattern, differs from classical lichen striatus in its quick resolution and frequent recurrence.The treatment of LS includes topical steroids and in recent times immune modulator drugs such as the calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus and pimecrolimus have shown efficacy in this setting [2, 14-15].

4. Conclusions

- Although lichen striatus usually presents on the limbs of children and adolescents, it can uncommonly be seen in adults on sites other than the limbs, for example the face, as our case demonstrates. Lichen striatus should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any linear acquired inflammatory dermatosis irrespective of the patient’s age or site of involvement. Furthermore, histological features very often help provide a definitive diagnosis, and so biopsy is recommended.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML