-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2014; 4(1A): 45-54

doi:10.5923/s.arch.201401.06

The Value of Housing among the Poor in Ilesa, Osun State Nigeria

Adedayo Ayoola1, Dolapo Amole2

1Department of Architecture, Federal University of Technology, Akure. Nigeria

2Department of Architecture, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile- Ife, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Adedayo Ayoola, Department of Architecture, Federal University of Technology, Akure. Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

To date, housing still remains a problem to many Nigerians. Despite the fact that various housing policy has been formulated and implemented in the past, there is a severe shortage of adequate and affordable housing for the poor who constitutes a high percentage of the urban populace. In examining this developmental challenge, this article emphasises the need to understand the values of housing among the poor and the application of appropriate development strategies that could enhance optimum utilization of existing resources for effective housing delivery. A brief background information on the Ilesa settlement and housing situation is discussed. Also, the socio-economic characteristics of the poor in Ilesa are well enumerated. The paper also presents the respondents on various issues on housing values (e.g., house type, house size, preferred tenure status, position of housing on the list of needs and willingness to pay for housing). The survey approach was adopted and the instrument used was the questionnaire. The questionnaire was administered to three hundred and fifty (350) household heads in two wards located in the core of Ilesa, using the systematic sampling technique. The questionnaire elicited information on socio economic characteristics, perceptions, values and preferences in housing. Three hundred and twelve (312) questionnaire were returned and used for the analysis. The data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Analysis of the result indicated that family well being (52.6%) ranked as the highest housing value followed by economy (34.3%) while personal/social expression ranked lowest (13.1%). The results of the study also showed that majority (99.7%) of the respondents’ preferred home ownership to other forms of tenure and (68.6%) would rather build with mud blocks. The preferred house types among the poor in Ilesa are self contained bungalow (51.5%) and rooming apartment (32.1%), there is also the preference for few numbers of rooms in their houses due to financial constraints. Willingness to pay for housing and infrastructure was high among the respondents. The paper concludes that researchers and designers needs information on values to explain housing preferences as a basis for design criteria.

Keywords: Sustainable development, Housing, housing value, Housing needs, Perception and poverty

Cite this paper: Adedayo Ayoola, Dolapo Amole, The Value of Housing among the Poor in Ilesa, Osun State Nigeria, Architecture Research, Vol. 4 No. 1A, 2014, pp. 45-54. doi: 10.5923/s.arch.201401.06.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Sustainable development is a development that meets the need of the present without compromising the ability of the future generation to meet their own needs and values [1]. The concept of ‘value’ in particular have been explained as things in which people are interested, want, enjoy or feel as obligatory. The wants of each individual or groups varies from one to the other, most especially the world’s poor who are powerless and suffers from all kind of deprivation. The housing needs of all citizens particularly the urban poor need to be given overriding priority and be adequately met because the satisfaction of human needs and values is the major objective of development. The Governments of various levels in Nigeria had tried to formulate different housing policies or programmes to ensure that all citizens own or have access to decent and safe housing accommodation at affordable cost. It is perhaps pathetic that the poor that form the vast majority of the population of most developing nations are not given any consideration in the formulation of these policies. Turner [2], for example, emphasised that the well intentioned housing projects often provided for low income families were not only costly, rigid, but also depressing for their users. Unfortunately, they could only house a relatively wealthy minority at the expense of the majority. He further argued that these policies were founded on the ignorance and misunderstanding of the housing and settlement process, and that they represented an application of planning and housing concepts based on the experience of modern countries. According to Hassan [3], the lower income housing areas receive corresponding poorer public services and social amenities due to an inherent evaluative mechanism and economic rationality which causes services and welfare bureaucracies to adversely discriminate against the poor who need their services most. The essential housing needs of majority of people especially in developing nations, particularly people in poverty are not met. Beyond their basic needs these people have legitimate aspirations for an improved quality of life. This has resulted in the various slums and squatter settlements scattered across cities in most developing countries.The concept of values has been used in different context with various dimensions of meaning. However, identifying housing values of people has been a tremendous task for researchers. Information on housing values has been used in the past to define housing preferences of individuals and also as a basis for housing design. Housing values vary from one individual to the other, it varies from one economic group to the other, and from culture to culture. Values which have explained variance in housing preferences or housing decision process has been defined according to Williams (1951), cited in Ha &Weber, (1992), values are defined as things people are interested in, things that they want, desire to be or become, feel obligatory, worship and enjoy [4]. Values are modes of organizing conduct, meaningful, effectively invested patterned principles that guide human action. Beyer [5] further explains value as the totality of a number of factors such as individuals’ ideals, motives, attitudes and tastes. These factors are often determined by cultural background, education, habit and experience. Several significant researches have been conducted on housing values in the past [4, 5 ,6 ]. Ha and Weber [1992] conducted research to assess the housing value patterns and orientation of households. Value ranking was patterned to follow the paired comparison format which included family, personal, economy and social value statements. Cutler, [6] in his own study of housing values tried to identify values that were important in peoples housing choice. The study was able to identify values in the following dimensions, beauty, comfort, convenience, location, health, personal interest, privacy, safety, friendship activities and economy. Subsequent researchers have also used cutler’s scale or an improved version to investigate peoples housing choice, value or preferences. Mc Cray and Day [7] used a revised cutler’s scale in his own study of housing values, aspirations and satisfaction of rural urban residents. Rural residents indicated a higher preference for conveniences than the urban residents while Humphries [8] also used the same approach to examine the housing values, satisfactions and goal commitments among multi-unit housing residents. He discovered variations in cluster patterns of apartment renters and town house owners. It is however worthy of note that much study have not been done on housing values among income groups. This paper will be investigating the value of housing among the poor in particular. The poor usually constitute a distinct group with specific characteristics and values which are different from the rich and middle class. Hence for effective policies and sustainable housing provision for the urban poor, the meaning, values and importance they attach to different sectors of life have to be considered. This is especially so in housing where different meanings are attached to housing by different social classes of people. Since the concept of value is about personal feelings and likeness, housing programmes should be based on genuine local participation in order to ensure sustainability. The local people are in the best position to identify their needs in order of their priorities. In order to achieve sustainable housing policy formulation, people at the grassroots level must be given the opportunity to participate [9, 10]. The aim of the present study is to evaluate what values the poor attach to housing with a view of providing sustainable housing to the poor. Specifically, the objectives were to:(1) examine the housing values of the poor in the choice of a home. (2) identify the trade-offs the respondents make between housing and other spheres of life.

2. Review of Literature

- Poverty defies objective definition because of its multi-dimensional nature. Poverty is a concept that has many definitions. Poverty has social, cultural, economic, political, religious and more recently, environmental and physical dimensions [11]. Most authors now agree that poverty has multiple dimensions which go beyond simple income consideration to encompass other qualitative aspects of life such as ill-health, illiteracy, lack of access to basic services and assets, insecurity, powerlessness, social exclusion, physical isolation and vulnerability. Poverty is generally defined in terms of a lack or deficiency in some form. It generally now seems to be agreed that poverty is more than income, people have been defined as poor in spatial terms and in relation to a lack of services which other urban area residents have access to, education, health, good housing conditions, water, electricity, appropriate sewerage, land ownership and secure tenure etc.Poverty has been defined as the inability to attain a minimum standard of living (World Bank Report, 1990). The report constructed two indices based on a minimum level of consumption in order to show the practical aspect of the concept. While the first index is a country-specific poverty line, the second is global, allowing cross-country comparisons (Walton, 1990). The United Nations has introduced the use of such other indices as life expectancy, infant mortality rate, primary school enrolment ratio and number of persons per physician.Poverty has also been conceptualized in both the “relative” and “absolute” senses. This is generally based on whether relative or absolute standards are adopted in the determination of the minimum income required to meet basic life’s necessities. The relative conceptualization of poverty is largely income-based or ultimately so. Accordingly, poverty depicts a situation in which a given material means of sustenance within a given society is hardly enough for subsistence in that society (Townsend, 1962). What is most important to deduce from these different definitions is that, poverty must be conceived, defined and measured in absolute quantitative ways that are relevant and valid for analysis and policy making in that given time and space. The reason for this is that the absolute definition has to be adjusted periodically to take account of technological developments such as improved methods of sanitation and infrastructural development.Housing, in general, is the process of providing a residential environment made up of shelter, infrastructure and services but to others, it means more as it serves as one of the best indicators of a person’s standard of living and his or her place in the society [12]. Housing in this context refers not only to the physical structures and buildings meant for people to live in, the neighbourhood and infrastructure. It also involves the process of acquiring land, labour and finance [2]. Despite the importance of housing to the poor, low income or poor household face several difficulties in their bid to acquire housing. Apart from the limitation of income associated with their low income status, they are also subject to discrimination and bias in existing policies, regulations and practices [13]. More often than not the investors tend not to see the poor as a potential consumer of their products and hence, the housing provided does not suit the need of the poor who constitute a vast majority of our urban populace.The needs of the user population differ from one income group to the other, for example, the low income group prefers housing in close proximity to the city centre and centre of employment. Such needs as security and identity are appreciated by the middle and high income earners [10]. Users’ needs are informed by the socio-economic circumstances of the individuals, their cultural background and world views, and the political economic situation of the country at large [10].In order to formulate an appreciable housing policy, policy makers and designers must understand the housing values of the various income groups especially the poor whose voices are seldomely heard.Housing values according to Beamish et al, [14] is the concept used to explain the preferences and choices of people in selecting different types of housing. Roske [15] further defined housing value as the underlying criteria for choice in housing and other aspects of life.

2.1. The Concept of Housing Values

- Housing value is the means by which individuals intend to live. Beyer et al [5] illustrated that the hierarchy of values were based on four main values: economy, family (physical, mental health and family centrism), personal (aesthetics, leisure and equality) and social storage. Follow up study by Beyer et al on housing value paid attention to two kinds of values namely freedom and social prestige. Beyer [5] describes the four values as follows:-Economy- families in this cluster emphasized the economic uses of goods and services. They base choices on the selling price and what they consider as affordable or sound business judgement.Family- they emphasise factors that hold families together and also improve family relationships. They tend to influence the physical and mental well being of family members.Personal- families in this category take personal view of their physical and social environment. They are more individualistic and also desire independence and self expression.Social- families in this category are considered upwardly mobile and housing is viewed in terms of its effect on their social standing.Lin Shi [16] also acknowledged that most households do not hold just one housing value, but a hierarchy of values. Even in one household, different members hold different kinds of housing values. Lindamood & Hanna [17] observed that in making housing decisions families have to make a tradeoff between their different housing values. Abraham Maslow in his hierarchy of needs acknowledge that human wants are unlimited and when one is achieved another need emerges [18]. In essence, a complete satisfaction is impossible. When this kind of situation arises, the most important values have to be met one after the other and certain trade- offs will be made.

2.2. Sustainable Development and Housing Provision

- Sustainable housing provision is the gradual, continual and replicable process of meeting the housing needs of the populace, the vast majority of who are poor and are incapable of providing adequately for themselves [19]. It ensures housing programmes that are able to satisfy the aspirations of the people and not policies based on political or cultural bias. Sustainable housing provision requires proper definition of housing needs, and the participation of the end users to ensure their satisfaction. The general goal of sustainable development is to meet the essential needs of the world’s poor while ensuring that future generations have an adequate resources base to meet their own needs [20]. In order to realize sustainable housing provision the housing needs of the Nigerian population have to be put into proper consideration, and a framework to achieve this should be thoroughly worked out. Sustainable housing provision is thus contingent on such underlying factors as policy formulation and decision making, policy execution and monitoring, and social acceptability and economic feasibility. These factors must take into cognizance the bottom-up participatory approach in housing provision involving genuine local participation by people at the grassroots level [21]. Without reference to the perceptions and values of the people, most housing programmes often fail. This is because people in poverty are in the best position to identify their needs, and order their priorities. Attitudes towards space, use and organization of space, are all linked to cultural traditions, which are often best understood by the poor themselves.Local settlements have vast understanding of their environment, their local building resources and the ways of making the best uses of them. Thus housing that will be acceptable by the local settlements must have put into consideration the cultural, climatic, socio-economic circumstances of the people. This kind of housing can only be achievable if suggestions are welcomed from within the communities. At the level of planning and decision-making local participation is indispensable to sustainable housing.

2.3. The Study Population and Study Area

- Ilesha city is one of the ancient cities in the Yoruba kingdom of the South Western Nigeria, in Osun State, with a population of about 334,000 (2008 population Census). Formerly a caravan trade centre, Ilesha is today an agricultural and commercial city. Cocoa, kola nuts, palm oil, and yams are exported from there. There is an abundance of alluvial gold deposit in Ilesa. Ilesha was the capital of the Ilesha kingdom of the Oyo Empire. After Oyo's collapse in the early 19th century, Ilesha became subject to Ibadan before it was taken by the British in 1893. The town is now divided into two local governments, which were established in 1991. (See Figures 1 & 2) The two local governments are Ilesa East and Ilesa West Local Governments and their headquarters are at Iyemogun and Ereja respectively. Ilesa East has eleven (11) administrative wards while Ilesa West has ten (10) administrative wards which represent the residential districts. The residential districts consist of the central core which is traditional in its setting and pattern and the new residential areas. The central core is made up of compound houses, where all members of the extended family lived together. A cursory analysis shows that like most Yoruba cities, the highest concentration of the poor is found in the core area. As the city grew away from the traditional core, new residential areas are formed which are made up of houses and apartments owned by individuals or rented by families.

3. Methodology

- The study employed the survey method. A semi-structured questionnaire comprising both qualitative and quantitative data was designed to elicit information on the housing preferences of the poor. The questionnaire consists of two parts. Part A deals with the socio-economic characteristics of the respondents while Part B deals with the respondents’ housing preference. In administering the questionnaire, the study area was stratified into the two existing local government areas in Ilesa, namely; (Ilesa East and Ilesa West.). The purposive sampling method was adopted to select the poorest ward from each local government. (See figure 1 & 2) Two wards were selected for this study, Ilesa East Ward 5 (Ijamo) and Ilesa West ward 4 (Omofe, Idasa and Ita ofa).

| Figure 1. Map of Nigeria Showing Osun State |

| Figure 3. Map of Ilesa Showing the Study Area |

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Socio-economic Background

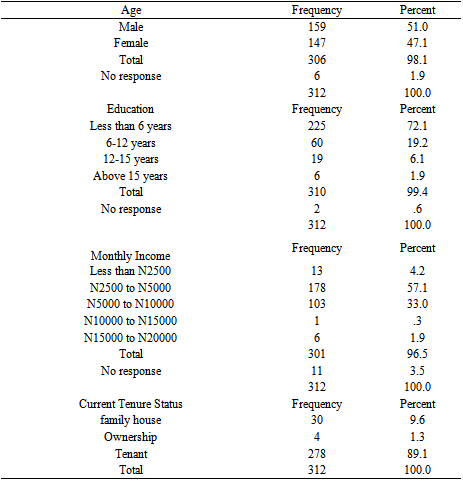

- The socio- economic variables investigated include sex, age, income, educational background and tenure status. Table 1 reveals that gender is evenly represented. Overall it can be seen that a total of 159 (51.0%) respondents were male while the female gender accounts for 147(47.1%).) The table also revealed that an overwhelming majority of the respondents 225(72.1%) had just primary school education while the university graduate are in a minority of 6 (1.9%). This confirms the literature (Jaiyeoba, 2011) that the poor has little or no level of education. It is noteworthy that the majority of the respondents are poor. Their very low monthly income depicts a high level of poverty among the respondents. As at September, 2010, 13(4.2%) of the respondents earned less than N2,500 per month, 178 (57.1%) of the respondents earned between N2,500 and N5,000 monthly, 103(33.0%) earned between N5,000 and N10,000 per month. The finding confirmed the United Nations (2009) findings that 61-80% of Nigerians citizens are poor based on the high level of people still living below the approved $1.25 per day ($37.5 per month= N5, 700 per month) in the country. The income of majority of the respondents fall far below the approved minimum wage (N7, 500) approved for civil servants in Nigeria. The study also revealed that majority of the respondents, 278(89.1%) lived in rented apartment while 30(9.6%) of them lived in family houses where they do not pay rents. Only a few percentage of the respondents, 4(1.3%) are home owners. The socio-economic background of the respondents reveals that poverty is evident in the study area. This has a lot of implications on residents’ ability to access housing and infrastructure. Poverty is one of the major hindrances to sustainable urban development.

|

|

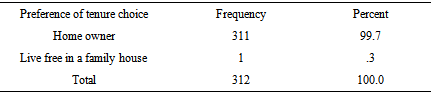

4.2. The Ranking of Housing on the List of Needs

- The result of the survey on the position of housing amongst the wish of needs of the respondents (Table 3) indicates that housing is ranked third after food and child education followed by personal business, clothing, vehicle and ranked lastly is marrying another wife. The result of the study shows that housing is very important in the life of the respondents. The implication of this is that, the respondents are willing to forfeit every other comfort of life for housing. Despite the situation they find themselves they are still ready to pay for housing. The result implies that home ownership is really a major part of the aspiration of the poor that must be met.

|

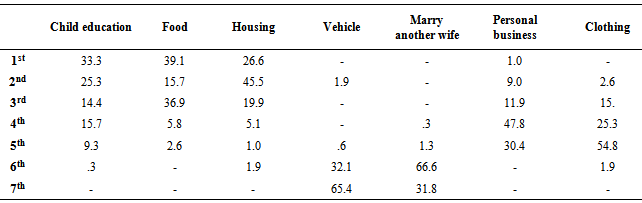

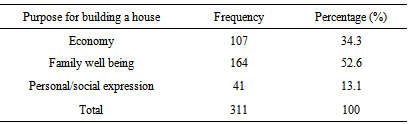

4.3. Ranking of Housing Values

- The ranking of three housing values were analysed to determine housing value ranking patterns based on the frequency of their selection. Family well-being appeared as the highest ranked value of the respondents, economic value was the second and personal/social expression last. The analysis of the respondents’ perception of what a house means (Table 4) indicated that the highest percentage (52.6%) ranked family well-being as the most important value while 34.3% of the respondents ranked economy as the second, they perceived a house as a means of increasing income. The least percentage of the respondents (13.1%) perceives a house as personal or social expression of self. These results are consistent with previous research (Ha and Weber, 1992). The implication of the result is that people in poverty also appreciate family values above all values. They value the comfort of their family above every other value. The implication of the result for sustainable housing is that culture and family background is a major determinant of housing choice.

|

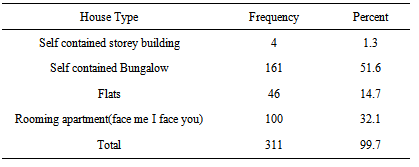

4.4. House Type Values

- Responses from the study (Table 5) show the highest percentage of respondents (51.8%) preferred to build a self contained bungalow while the lowest percentage (1.3%) preferred to build a self contained storey building. The study also showed that 32.2% of respondents’ preferred to build rooming apartment (face me i face you) while 14.8% of the respondents preferred to build a flat. Majority of the respondents had preference for self contained bungalow for family comfort and privacy. Income was also cited as a reason for their choice. The implication of the result indicates that family comfort and means of making income is a major reason behind the choice of houses the poor prefers. Asides the fact that they cherish their comfort they also want to make money from housing.

|

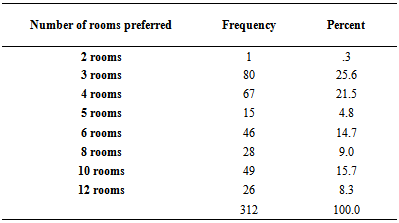

4.5. Room Numbers Values

- Table 6 shows that 25.6% majority of the respondents preferred 3 rooms, 21.5% of the respondents preferred 4rooms while 15.7% indicated their interest in 10 rooms, 14.7% preferred 6rooms, 9% prefers 8rooms and 4.8% indicate their preference for 5 rooms. These results show that the respondents preferred fewer number of rooms (3-bedroom and 4-bedroom) in their houses. The reason for their preference was based on privacy and affordability. However these results do not correlate with findings from other researchers like Jaiyeoba, [23] whose findings revealed that the low income earners preferred higher numbers of rooms for commercial purposes. Predictors of preferred number of rooms can be linked to the location and purpose why people want to build. The poor in Ilesa are willing to build what they can afford at the moment for their own personal use.

|

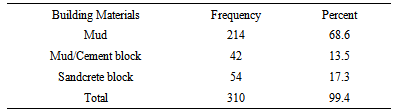

4.6. Building Material Values

- The study examined the type of materials the respondents preferred to build with (Table 7). The highest percentage of respondents (68.6%) preferred to build with mud while the lowest percentage (13.5%) are those who would build with mud/cement block. Few of the respondents (17.3%) would rather build with sandcrete block. However two (2) of the respondents did not answer the question. The result corroborated findings from researchers like Agbola, [24], and Agarwal, [25], who are of the view that mud block should be encourage as a building material to be adopted by the poor in building their own houses because it is cheap and readily affordable.

|

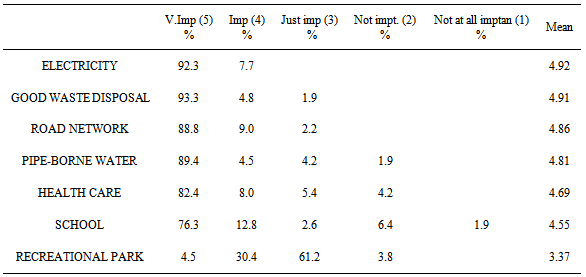

4.7. Ranking of Infrastructural Facilities in the Housing Environment

- The values the respondents attach to housing facilities indicate how important these facilities are to their housing.In measuring the level of importance of infrastructural facilities within the housing environments, respondents were asked to rank on a five point scale ranging from very important to not at all important. Table 8 shows the results of the analysis carried out on this issue.

|

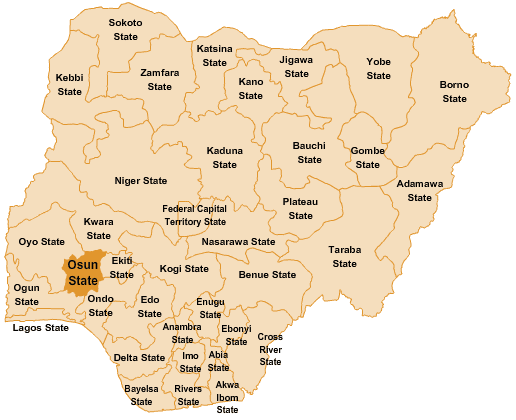

4.8. Willingness to Pay for Housing

- The study showed the analysis of the amount the respondents are willing to spend to construct a house. In Table 9, it can be seen that the highest the respondent can pay for housing is between N451, 000-N500, 000 while the least they are willing to pay is between N10, 000- N50, 000.

|

4.9. Predictors of Housing Values among the Poor

- There is a need to understand the relationship between housing preferences of the poor and socio-economic characteristics of respondents. This is with a view to understanding which of the socio-economic characteristics influences their housing preferences. The literature however observed that some socio-economic characteristics of the respondents like gender, age, education and income may influence people’s value to their housing.To fathom an explanation for the significant factors that may have been at play in the different housing values, a categorical regression was done.The analysis of all socio economic characteristics of the respondents and the preferred house size yielded a significant model (F9.271; p < 0.001), with adjusted R square = .173. This implies that the model explains 14.1% of the variance in the preferred house size, meaning other factors was at play. The significant predictor variable in this model were age (F= -.169, p < 0.001), education (F= -.224, p<0.001) and income (F= -.209, p <0.001) for income. All the socio economic factors influences preferred house type except sex. This is reflected in their beta weight value which is < than 0.001 and statistically significant. The factor that influences preferred tenure status is income (F=-.454, p< 0.001). The implication of the result is that a socio-economic characteristic affects people’s values of housing. This means peoples values are not constant and they vary from one person to the other. It is based on this that this study investigates the housing value of the poor.

4.10. Implications for Sustainable Development of Housing

- The socio-economic backgrounds of the respondents revealed that majority of the respondents are poor as they live far below the approved poverty line. They also have very low level of education as majority of them have just primary education. These have affected the quality of life in the environment. The respondent ranked infrastructural facilities as very important in their housing and irrespective of their low level of income they are willing and ready to pay for housing.Despite the fact that home ownership is the preferred housing tenure, majority of the respondents still live in rented apartment because they are poor and could not afford their own housing. Result of the study also indicated the housing preferences of the poor. Majority of the respondents (51.8%) preferred to build self contained bungalow for privacy and family comfort while the preferred number of room is 3bedrooms due to financial reasons. In order to realise sustainable housing provision the exact need of the people must be considered. This is necessary because the need of the people varies from one group to the other, and in order to provide housing that will be affordable and satisfactory to all group particularly the poor their needs must have been considered.The preferred building material among the poor is earth. Nigeria is currently experiencing drastic economic hardship and the building industry has been massively hit. The prices of imported materials have gone beyond the reach of the poor. If housing will be affordable for the masses there is the need to embrace indigenous building materials because they are cheap and readily available. This study has been able to confirm previous researches on general housing value patterns and also establish housing values of the poor. The study confirms previous researches that ranked family well being and economy as the highest value. The study has also been able to establish that socio economic factors also influence value. The result of the study will guide designers and policy makers in their decision process to understanding how people’s socio-economic characteristic influences their housing values.Now that we know the housing value of the poor from the study, it is necessary that the government’s policy on housing should reflect distinct characteristics, perception and values of the poor. Major reason for the failure of past housing policies could be traced to the lack of understanding of the wish of the people especially the poor who form a large majority of our citizenry.

5. Conclusions / Recommendations

- This study was carried out at Ilesa in Osun State, Nigeria. The main aim of the study is to examine the housing values of the poor who are mostly faced with the challenges of affordable housing. The previous attempts by government to provide housing for low income families has not yielded result, as the houses provided were too costly and unaffordable for the poor. The various National Housing Policy put in place by government in the past has failed to provide Nigerians access to a decent housing accommodation at affordable cost as a result of a limited understanding of what the users want or value.Achieving sustainable development requires a responsive housing policy that will be in consonance with the existing national and socio-economic realities of the country. There should also be a clear understanding of the meaning of housing to the poor, how important it is and its value to them for good policy formulation. In this regard, relevant housing development strategies should be identified and integrated to form part of existing housing policy. Part of the strategies should ensure and encourage greater participation of ordinary citizens in the affairs of their city and town through a degree of power decentralized to local authorities. Existing policy or programme should be reviewed to ensure adequate infrastructural development alongside housing delivery as well as the overall urban development.Also, to achieve this sustainable housing policy and programmes required to meet the housing needs of the people within available resources, due attention must be given to the culture, economy and history and social aspect of the people. It is also necessary to understand how the people live in terms of the type and quality of environment; how these have affected their productivity and performance in the economy in terms of minimum standards of space, dwelling types and community facilities they could access. From all indications, all the above parameters would further ensure a better housing policy formation.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML