-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2014; 4(1A): 34-44

doi:10.5923/s.arch.201401.05

Spatial Implications of Street Trading in Osogbo Traditional City Centre, Nigeria

Joseph Adeniran Adedeji1, Joseph Akinlabi Fadamiro1, Abiodun Oluyemi Adeoye2

1Department of Architecture, The Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria

2Department of Architectural Technology, Osun State Polytechnic, Iree, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Joseph Adeniran Adedeji, Department of Architecture, The Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Street trading is one of the misuses plaguing the public open spaces in third-world cities. The effects of the activity on accessibility in city centres have transformed them into contested places for incompatible functions. The aim of this study is to analyze the characteristics of street trading and its implications on urban open spaces vis-a-vis the landscape and accessibility in the city centre. Purposive sampling of 12 streets and their streetscapes that are mostly used for informal trading in Osogbo were investigated. Total sample size of 180 informal traders was randomly selected from the streets to elicit necessary information on their activities. A descriptive analysis of the data collected through physical observation and questionnaire survey was carried out. The results show that the activity has serious negative impacts on accessibility, erection of illegal structures, traffic congestion, solid waste generation, auto-accidents and deface of urban aesthetics. Control option favours inclusive principles of postmodernism in the landscape design of streets and streetscapes as public infrastructure. The study concludes with recommendations on urban renewal strategies to ameliorate street trading in Osogbo and approach that could be adopted in other cities of developing countries at large.

Keywords: Cities, Illegal structures, Privatization, Public open spaces, Streetscapes, Street trading

Cite this paper: Joseph Adeniran Adedeji, Joseph Akinlabi Fadamiro, Abiodun Oluyemi Adeoye, Spatial Implications of Street Trading in Osogbo Traditional City Centre, Nigeria, Architecture Research, Vol. 4 No. 1A, 2014, pp. 34-44. doi: 10.5923/s.arch.201401.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Streets are the fundamental public spaces in every city, the life of social and economic exchange [1]. They are the paths of the traditional and modern cities through which the activities that sustain cities flow [2]. Thus, streets in cities symbolically represent the blood vessels in humans [3]. According to Sennett [4], since the beginnings of the Baroque era, urban designers and planners had thought about making cities in terms of efficient circulation of people on the city’s main streets. People, traffic and society, in their systematic movement through what Sennett identifies as the “arteries” and “veins” of the city, provide a life within the constructed body of the city. The society thus forms the metaphorical blood that courses through the city’s veins [5]. Unfortunately, the overflow, the wrong flow and the incompatible flow of human activities circulation along these veins and arteries are symbolic of a diseased city-body dying and decaying under the negative influences of street trading. This unequivocally suggests the need for diagnosis and prescription of environmental medication for the city-body, especially in the traditional cities of developing nations. In particular, the spatial impacts of street trading deserve attention.The significance of the street as a major component of urban form is thus evident. In terms of land use generally, accessibility and movement through the streets are premised upon economic activities. Tanimowo and Atolagbe [6] posit that relationships exist between intra-urban travels and urban land uses as a reflection as well as a determinant of the level of economy of an urban system. They argued that there is no urban economy without the land use activities and travels among them and that the activities and functions of the city are defined by its economy. Unfortunately, the city centres of unplanned traditional urban places are not in good spatial arrangements to enhance these relationships. As such the emerging volume of economic activities, both formal and informal, cannot cope with the required accessibility demands with resultant negative outcomes. Handy, Paterson and Butler [7] argue that a connected road network provides better accessibility, which is essentially lacking in traditional cities. This is true because linkages of circulation in terms of people and goods are important element of land use plan [8]. Furthermore, human beings are not made of one part but many. Similarly, in streetscape discussions, like another “living organism” the urban enclave is woven of many inter-related and inter-dependent fabrics. These include social, economic, political, educational and physical elements among others. In this gamut, the economic sector is often the “soul” or the “life-wire” and when it malfunctions the whole system is affected. In view of the high rate of urbanization in Africa which is presently put at 39% and urban Growth Rate of 3.2 (2005-2010) [9]; the economic sector of cities which naturally divides into formal and informal aspects is over-flooded. The formal sector, generally characterized by legality, statutory licensing, organization, and specific procedure of documentable mode of operation has been the traditional major employer of labour in urban centres. However, because of high rate of unemployment and poverty consequent upon geometric rate of urbanization and economic downturn, the informal sector is captured by Cross [10] as “economic activity that takes place outside the formal norms of economic transactions established by the state and formal business practices…..it applies to small or micro-businesses that are the result of individual or family self-employment. It includes the production and exchange of legal goods and services that involves the lack of appropriate business permits, violation of zoning codes, failure to report tax liability, non-compliance with labour regulations governing contracts and work conditions, and/or the lack of legal guarantees in relations with suppliers and clients.” It is characterized by easy entry and exit; reliance on indigenous resources; labour intensive and adapted technology; skills acquired outside the formal school system [11, cited in 12], and is now the highest employer of the urban work forces, not just in the African region but globally. For instance the informal economic sector accounts for up to 75% of non-agricultural employment in the Gambia [13], about 50% in Thailand, 75% in Morocco, 70% in Bangladesh (47% of construction and 95% of public transportation in the capital city of Lima), 51% in Philippines[14, cited in 15]. According to the World Bank [16] and Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia [cited in 15] the informal sector is estimated to account for about 75% of the total employment in sub-Saharan Africa, 89% in Pakistan and 75% in Brazil, 48% of non-agricultural employment in North Africa, 51% in Latin America and 65% in Asia. On the whole, informal sector in Africa is estimated to account for 60% of all urban jobs and over 90% of all new urban jobs [9].In Nigeria, the situations of urbanization, the scale of informal economic activities and their implications on the accessibility in city centres are not too different from those described for other parts of the globe. Nwaka [17] noted that Nigerian estimates at the turn of 21st century suggest that 43.5% of the population were living in urban areas, up from 39% in 1985, with projections that the urban population will reach 50% by the year 2010, and 65% by 2020 while the rate of urban population growth is thought to be 5.5% annually, roughly twice the national population growth rate of 2.9%. Arguing that information on the size and employment structure in the informal economy is hard to obtain, he posited that estimates suggest that the sector accounts for between 45% and 65% of the urban labour force, up from about 25% in the mid-1960s. Similarly, Adeyinka et al [15] argued that the informal economy in Nigeria accounts for about a third of the 50 million labour forces out of 123.9 million people in 1999. The informal economy is the highest employer of the urban poor because of the inability of the formal sector to cope with demand for jobs, goods and services [18]. These describe the consequential magnitude of the spatial impacts of street trading on the accessibility in traditional city centres with narrow, mostly unplanned and improperly laid out streets, including other outcomes.The concern of this study therefore is the analysis of the characteristics of street trading and its spatial implications on accessibility in the city centre of Osogbo, Nigeria with the view to recommending between exclusive approach of modernism and inclusive strategies of postmodernism. This is necessary because the urban public space has come to be defined by the architecture of the streets and this phenomenon has emerged as the fundamental defining character of the image of towns and cities [19, cited in 20].

2. Statement of Problem

- The informal economic sector operates majorly in public open spaces and is a generator of illegal or temporary structures like sheds and kiosks. It manifests in unauthorized street trading, indiscriminate occupation of public space in defiance of formal planning and land use arrangements, little regard for intrinsic beauty and suitability, zoning problems and land use conflicts, impediments to free flow of pedestrian and motorized traffic and congested transportation networks [21; 22; 23 cited in 20].Furthermore, as typical of other traditional African cities Osogbo urban streets and major traffic arteries and nodes that ought to enhance urban viability, facilitate social exchange, and provide urban aesthetics in terms of street landscaping and differentiation of peculiar traffic routes to enhance conviviality are presently infected with street trading activities and the accompanying illegal or temporary structures and waste generation. The indiscriminately located informal structure are placed either directly on the street or street precinct and goods displayed in them are spread directly to the street leading to business transactions right on the street!This has led to heavy competitive use of the same street space for vehicular and pedestrian circulation, cyclists, motorcycles and commercial activities. Every inch of open space along the major streets and transport nodes are used for one informal commercial activity or the other breeding high rate of undesignated and incompatible land uses and turning the streets to confused and highly contested traffic routes. Hence, the need for an analytical study of the situations in the city centre and recommendations for effective and workable solutions for sustainable functional urban streets.

3. Osogbo: The Study Area

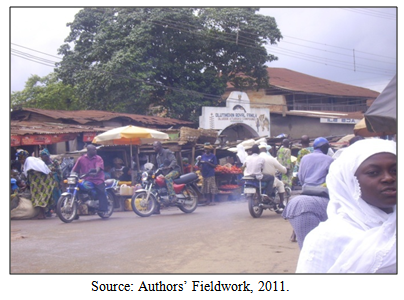

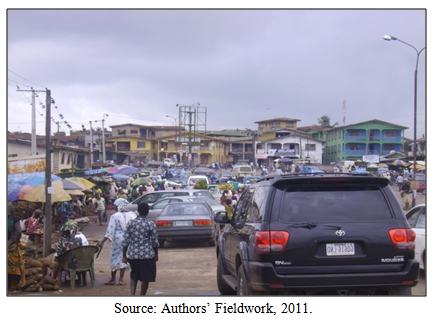

- Osogbo is a pre-colonial Yoruba ethnic city in the southwestern Nigeria located on Latitude 70 46’ 0” North and Longitude 40 34’ 0” East. The city has served as a commercial node since 1907 when the Nigerian railway station was established and the rail line passed through the town. Also, the city was the administrative headquarters of the former Osun Division. Currently, Osogbo with a total population of 139,573 according to the 2006 census [24] is the capital city of Osun State with well established formal commercial activities. The city is also the headquarters of Olorunda Local Government in the North and Osogbo Local Government in the south and has part of it in the west as Egbedore Local Government Area.The scale and pattern of informal structures and street trading varies within Osogbo. The traditional core of the city comprising of Oja-Oba, Olu-Ode and Isale Osun districts house informal commercial activities in spaces between buildings and in the residential units which largely consist of trading verandahs, sitting rooms converted to shops or shops attached to them and the two major “street markets”, Oja-Oba and Olu-Ode (Plate 1). In these street markets, informal businesses are carried out right on the street, in kiosks, workshops, sheds, under big umbrellas and corner shops. Oja-Oba doubles as a street market and major transport node and also as the nucleus of the Central Business District (CBD) in the Core Areas of the city (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Showing the major streets and Core, Intermediate and New Areas in Osogbo, Nigeria |

| Plate 1. Showing a typical street trading scene at Olu-Ode Street Market, Osogbo, Nigeria |

| Plate 2. Showing a typical street trading scene at Alekuwodo Street Market, Osogbo, Nigeria |

4. Theoretical Issues and Literature Review

- Intellectual debates on the best perception of the informal economy and street trading in particular based on inclusion or exclusion positions in public policies, impacts on urban land use and sustainable development, legality or illegality, categorization, economic roles and negative environmental impacts are established in the literature even though Nigerian case studies are scanty. The informal sector comprise of both mobile and stationary classes. Some of the mobile operators use motorized means like trucks and cars selling a range of items from herbal drugs, food items to sales promotion of GSM operators with heavy noise pollution. Others push carts, wheel barrows or hawk the goods placed on their head from one point of the street to another. The stationary class operates from informal structures who also at other times only use the structures as a distribution point for their goods or send out their young ones to hawk goods and services on the streets especially at peak traffic periods of the day while personally engaging in the enterprises at those stationary points. All the groups described above naturally fall within Cohen et al’s [25] most visible informal workers. The other two major classes according to Cohen et al’s classifications based on degree of visibility are the least visible informal workers who operate from homes selling or producing goods and services and the less visible workers who operate from small factories or repair workshops.According to Carr and Chen [26], the International Labour Organization is in support of informal-sector activities arguing that its inevitability has been recognized. Mitullah [27] insisted that “street and informal traders require laws that recognize their economic activities as an important component of the urban economy, and ensure their right to trading space”. Similarly, Obudho and El-shakhs [28] argued that the urban informal sector is one of the African urban system uniqueness and provided socio-cultural reasons for its home-based enterprises while Adeyinka et al [15] recognized that the urban informal sector activities play important roles in providing jobs for the teeming unemployed populace in Nigeria. Other “inclusionists” and “legalists” proponents include Manuh [29], Simon and Anders [30]. Simon and Anders [30] insist that the informal sector is “the process of enhancing individual and collective quality of life in a manner that satisfies basic needs, is environmentally, socially and economically sustainable, and is empowering in the sense that people concerned have a substantial degree of control over the process through access to the means of accumulating social power”. Similarly, Manuh [29] argue that the informal sector is a “safe haven” in view of its low capital requirement and ease of entry. They criticize the formal rules as unreasonably excessive, bureaucratically cumbersome and increases transaction costs [31]. The foregoing positions have been constantly faulted by the “illegalist” and “exlusionist” Schools on the Informal Sector. Their argument against the sector is premised upon key motivation as deliberate avoidance of operating overheads such as electricity and rental fees, commercial regulations and evasion of taxes as opposed to the formal sector [32; 33]. They recognize the unregulated activities of the informal sector as the origin of the worsening health and environmental problems of cities and argue that “if the informal sector thrives because of its informality, and because rules and regulations are minimal; does it make sense to try to formalize and integrate it into the formal economy with laws, codes, and standards that could disrupt its activities and growth?” [17].Street vending activities have been associated with improper disposal of refuse like in Lagos megacity which represents the extreme case of the accumulation of rubbish heaps in road mediums [20]. This and other negative consequences of street trading and informal commercial structures are most likely to increase in view of Skinner’s [9] argument that “the combination of urbanization, migration and economic development trends suggests that there has been a rapid increase in the number of street traders operating on the streets of African cities.” Consequently, eviction of street traders and demolition of informal structures is an international trend [34] just as there are already cases of street traders being removed in South Africa [cited in 9]. Kamunyori [35] reports that the council inspectors in Nairobi are constantly bribed by street traders to avoid eviction.According to a study of physical and socio-economic impact of street trading in Ibadan by Adeagbo [36], 77.8% of the street traders had shops but engaged in street trading due to lack of patronage, 22.2% of them cited inaccessibility to customers as reason for engaging in street trading and 91.7% claimed negative impact of weather on them. The study also discovered increase in travel time and period of discomfort for both passengers and pedestrians [37]. Enogholase [38] reported that no fewer than 15 persons were prosecuted by the mobile court in Benin, Edo State of Nigeria who contravened the state’s law on street trading on September 30th, 2009. In Owerri, Nigeria, it was discovered in a study by Chukuezi [39] that “most traders choose to mount their stalls at the intersection of major roads where there is a mix of commercial, residential and business properties where they would take advantage of high volume of customers both during the day and at night” while some traders display their wares along the curbside or the pavement. The study noted the encroachment to the road, space and creation of congestion, noise and garbage, unsanitary and hazardous workplaces that lack basic services.In Lagos metropolis, “informal entrepreneurs tend to construct their make-shift kiosks along drainage channels and also dump domestic wastes indiscriminately into drains, thereby causing blockage and consequently floods are frequently experienced in Orile and Coker” [40]. It was also posited that informal enterprises is a great threat to the environment, usually operating without authorization on public or private land, engage in illegal subdivision and rental of land and carry out unauthorized construction of informal structures [40]. The study of Adeyinka et al [15] on land use implications of informal sector in Lagos State equally revealed that kiosks, shops, temporary structures and open spaces are used for trading activities and are constructed of planks, bricks and blocks. The result of the study showed haphazard and uncoordinated development, encroachment of structures on streets and walkways with attendant reduction of road capacity especially at night resulting into congestion, pollution and filtration. Similar study [12] in Ogbomoso revealed the linear pattern of the informal sector enterprises using illegal structures along major transportation corridor and argued that the sector provides supplementary services to the major land uses making it “imperative that the sector is well integrated into land use planning process”.

5. Methodology

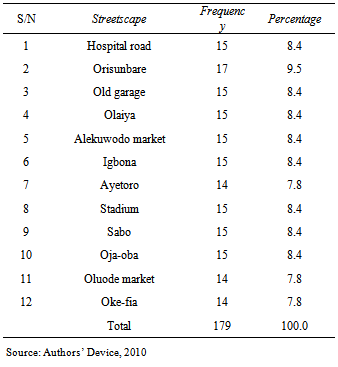

- Twelve most well-established street trading locations in Osogbo were purposely selected as shown in Table 1. These locations are major traffic routes and some of them are either illegal extensions of purpose-built markets or streets that are used as “markets”. The data collection instrument consisted of structured questionnaire, administered by trained Research Assistants that contained close-ended questions on characteristics of street trading and associated informal structures majorly gleaned from related literature.

|

6. Discussion of Findings

6.1. Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Street Traders

- Out of the 180 (100%) structured questionnaires administered, a total number of 179 (99.4%) was returned. Concerning the gender of the respondents, 107 (59.8%) were females, 70 (39.1%) were males. In view of this, the study corroborated the female gender bias of street trading.The age categories of the respondents were indicated as follow: 18-30years, 68(38.0%); 31-40years, 62(34.6%); 41-50years, 30(16.8%); over 50years, 15(8.4%); no response, 4(2.2%). This age pattern shows that majority of the street traders are less than 40 years of age, with the age bracket of 18-30 years being the highest. For them, street trading activities is their economic base and means of livelihood since they could not be employed in the formal sector.The marital status of the traders were indicated in the following descending order: married, 106(59.2%); single, 50(27.9%); widowed, 9(5.0%); separated, 5(2.8%); divorced, 2(1.1%); no response, 7(3.9%). The 106 number of married street traders meets their family needs with the income from the activity. The educational level of the respondents reveals a disturbing trend in the socio-economic life of the country. Secondary school leavers were 62 ((34.6%), 54(30.2%) had either NCE/HND or B.Sc. while primary school certificate holders were 35(19.6%) and 26(14.5%) had no formal education. 2(1.1%) of the respondents did not reveal their educational status. This pattern shows that street trading is no more for the illiterate folk but also engaged in by part of the multitude of unemployed higher institution graduates.The average monthly income level of the street traders was also revealed by the study as follow: 57(31.8%) earned below N5,000.00, 39(31.8%) earned between N5,000.00 and N10,000.00, 18(10.1%) earned more than N10,000.00 and up to N20,000.00, 12(6.7%) earned more than N20,000.00 and up to 30,000.00 while 40(22.3%) earned above N30,000.00. 13(7.3%) of the respondents did not respond on their average monthly income. A comparison between the highest educational level of 54(30.2%) and the number of highest monthly income level of 40(22.3%) indicate a serious low economic benefits of street trading activities for the highest educational level. Only about 29% earned above the country’s minimum wage.

6.2. Informal Structures and Construction Materials for Street Trading

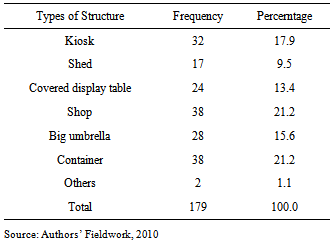

- Table 2 shows the types of informal structures used for street trading activities in Osogbo.

|

|

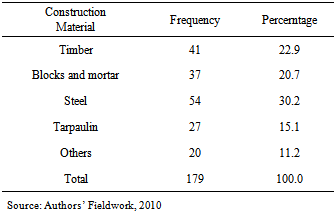

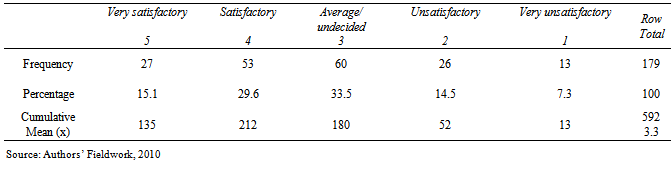

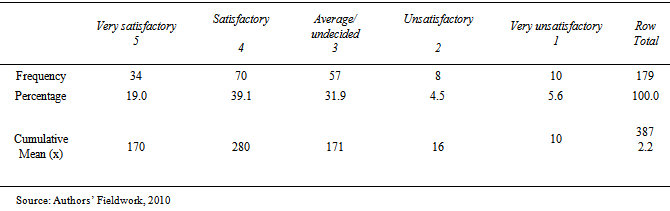

- The highest frequency for steel, 54(30.2%) here indicate a negative implication for the environment and users of these steel structures. This is true because steel is not biodegradable, has high heat storage capacity, high thermal conductivity, impairs users comfort and builds general environmental discomfort. This fact is better explained by Table 4 below showing the thermal comfort of the user street traders at hot periods on a 5-point Likert scale.From table 4, the mean (x) for the thermal comfort satisfaction measure at hot periods, which is most prevalent being in the tropics, of the street traders using these informal structures is 3.3. This value is below the satisfaction level of 4 and tends towards the unsatisfactory side of the Likert scale.

|

6.3. Social Amenities, Accidents and Government Raids

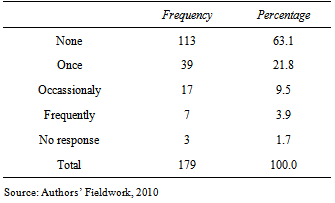

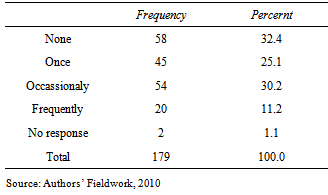

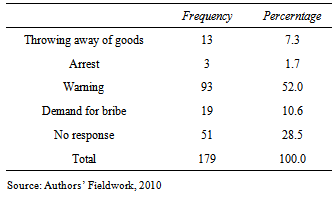

- Access to social amenities by street traders at the trading points was revealed by the study. 66(36.9%) had access to pipe borne water, 110(61.5%) had no access to pipe borne water while 3(1.7%) gave no response on this variable. Furthermore, 115(64.2%) had access to electricity supply, 62(34.6%) had no access to electricity supply while 2(1.1%) gave no response. Generally, the electricity supplies to those who have access to it have been acquired illegally being connected from nearby residential supply. In this way, the street traders are not paying commercial bills if they ever pay on the use of public social amenities. The same also applies to water supply which was primarily planned for the adjacent residential or institutional neighbourhoods. The problem of inaccessibility at street trading points is encapsulated and manifested in busy and heavy traffic volumes that lead to auto-accidents. Table 5 shows the incidence of auto-accidents at the trading points due to incompatible vehicular, trading, pedestrian and cyclists’ activities. From table 5, 39 (21.8%) experienced accident once, 17(9.5%) experienced accident occasionally, 7(3.9%) experienced accident frequency, 113(63.1%) indicated no experience of accident while 3(1.7%) gave no response.

|

|

|

|

|

6.4. Trading Activities, Waste Generated and Management

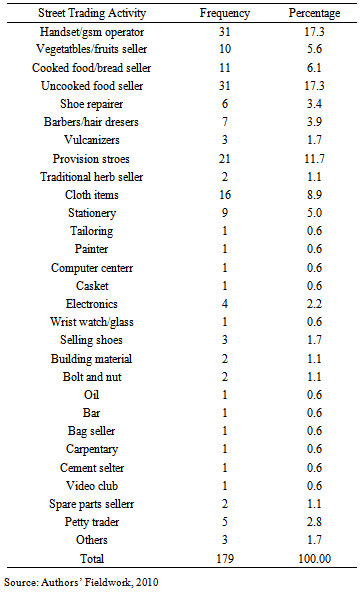

- Table 10 below indicates the types of trading activities from the study. High in the effects of street trading activities on major essentials of life are uncooked food seller, 31(17.3%); cooked food/bread seller, 11(6.1%); vegetables/fruit seller, 10(5.6%); provision stores, 21 (11.7%; all these giving a large total of 73(40.7%). The number of handset operator was 31(17.3%) followed by cloth items, 16(8.9). This pattern supports Maslow’s [41] physiological requirement of food in the hierarchy of human needs even though communication is also very important, this being an information age.

|

6.5. Street Traders Residence, Primary Employment, Number of Trading Locations, Years in Street Trading and Most Selling Time

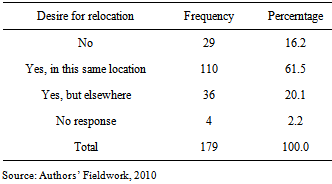

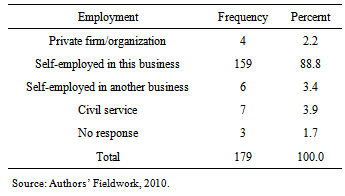

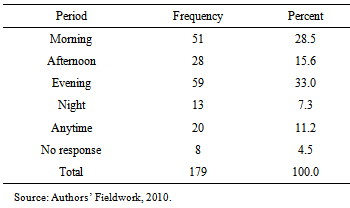

- The locations of the residence of the street traders in relation to their respective trading points were also identified. About 61(34.1%) live around their selling points, 52(29.1%) live about 1km away, 49(29.4%) live about 2km away, 1 (0.6%) live about 3km away, 12(6.7%) live more than 3km away while 4(2.2%) did not disclose their residences possibly for fear of prosecution. This picture indicates that majority of the traders live in the proximity of their selling point which to them will reduce or completely eliminate cost of transportation in order to maximize their profits. It is also very instructive that new urban residential neighbourhoods should be adequately planned to include necessary commercial facilities like corner shops and neighbourhood mini-markets for convenience of residents and traders especially for daily needs.Table 11 shows the employment pattern of the street traders. Majority of the respondents, 159(88.8%) are solely and self employed in that business, 6(3.4%) are self-employed in another business, 7(3.9%) are civil servants, 4(2.2%) are primarily employed in a private form/organization while 3(1.7%) decline their response. It is thus clear that the high rate of unemployment in the country is being stemmed by the informal sector including street trading.

|

|

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The study has revealed the values and vices of street trading. Attempts by the government in the past to deal with the situation proved abortive. This may not be unconnected with the non-inclusive approaches to solving the problem. The current situation intelligently suggests that inclusive principles of postmodernism should guide the solution to street trading problem in our cities to completely eliminate its vices or reduce it while benefiting from its values. With the emergence of post modernity it was found that street trading is a thriving and growing phenomenon that can be attached to the existing changes in the global economy [10]. Through postmodernism, a realistic response to the economic, cultural and social world of today is fashioned and individuals are able to gain control over their lives [42]. Postmodernist planning is thus more open towards the informal sector and it is expected to solve the problems of the informal sector by becoming formal. Consequent upon this understanding, the following recommendations become necessary: 1. Government at all levels should collaborate to embark on urban renewal project that will provide appropriate-sized shopping facilities at an appropriate space in the street trading points possibly by changing certain existing land-use if necessary.2. At the completion of such facilities, the removal of all informal trading structures should be enforced under the Development Control modality by relevant government agencies.3. The Ministry of Environment should embark on city-beautification scheme of necessary landscaping of the current street trading points.4. Existing environmental laws on street trading should be evaluated and if necessary reviewed for enforcement where they exist and new laws should be promulgated where necessary.5. Street Trading Control Task Force should be constituted and empowered to prosecute offenders to face the wrath of the law.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML