-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Architecture Research

p-ISSN: 2168-507X e-ISSN: 2168-5088

2014; 4(1A): 15-26

doi:10.5923/s.arch.201401.03

Trends in Urbanisation: Implication for Planning and Low-Income Housing Delivery in Lagos, Nigeria

Akunnaya Pearl Opoko, Adedapo Oluwatayo

Department of Architecture, Covenant University, Ota, Ogun State, Postcode 110001, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Akunnaya Pearl Opoko, Department of Architecture, Covenant University, Ota, Ogun State, Postcode 110001, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Urbanization is a global phenomenon which is currently sweeping through developing countries like a wild fire. As a result of the magnitude and speed of urbanization in these countries many governments appear overwhelmed and unable to cope with its challenges. Consequently, basic infrastructure and services are rarely provided as urban growth proceeds haphazardly with severe threats to the well-being of the people and society. Lagos, Nigeria is one of the largest urban areas in the developing world which is currently grappling with the challenges of urbanization especially in the area of housing provision. The present work has been motivated by the current severe inadequate housing in Lagos. It is based on extensive literature review and archival retrieval of historical documents. The paper identified some salient features of the urbanization process in Lagos, Nigeria and the challenges they pose to adequate housing. These include rapid population growth and changing demographic structure; poverty and unemployment; difficulties in accessing housing delivery inputs; and lack of adequate capacity on the part of government. The paper further examined the implications of these challenges for providing housing especially for poor households and concluded that urbanization of developing cities if properly managed should bring about economic and social development.

Keywords: Urbanization, Low-income, Households, Housing delivery, Lagos

Cite this paper: Akunnaya Pearl Opoko, Adedapo Oluwatayo, Trends in Urbanisation: Implication for Planning and Low-Income Housing Delivery in Lagos, Nigeria, Architecture Research, Vol. 4 No. 1A, 2014, pp. 15-26. doi: 10.5923/s.arch.201401.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Urbanisation is not a recent phenomenon. Since the early 1800s, movements of people especially from the rural areas to more urban areas have been recorded [1]. Consequently, population of people residing in urban areas increased from 13% in 1900 to 49% in 2005 [2]. Numerically, this represented a move from 220 million people in 1900 to 3.2 billion people in 2005. By 2011, there were already 480 cities with populations in excess of one million as against 80 of such cities in 1950. Currently, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities [3], [2]. More than three billion people currently reside in urban centers and this figure is expected to rise to five billion by 2050. Perhaps most striking is the fact that most of the population growth in the coming decades will occur in low- and middle-income countries [1]. Africa is reportedly a late starter in the urbanization race [4]. However, it is urbanizing at such an alarming rate that predictions suggest Africa will enter the urban age around 2030 when half of Africans will live in urban areas [5], [4]. Nigeria is notably the most populous African nation and predicted to drive this population growth [6]. At current growth rate, one of its cities, Lagos will be the third largest city in the world with a population of over 24m by 2020 [7].Urbanization is driving the economies of most of the nations of the world especially developed nations [8]. Living in cities offers individuals and families a variety of opportunities [2]. It brings with it possibilities of improved access to jobs, goods and services for poor people in developing countries and beyond as globalization connects cities world-wide [1]. Being hubs for civilizations and culture and with their unquestionable potential, they are expected to offer employment, shelter, stability, prosperity, security, social inclusion and more equitable access to the services. All these, according to [5] would make lives safer, healthier, sustainable and more convenient.Urbanization in developing countries has followed a different trajectory from the above premise, leaving many overwhelmed urban residents and their governments in frustration, despair and confusion [9]. The physical manifestations of rapid urbanization in many developing countries like Nigeria are often chaotic and reflective of the profound and far-reaching demographic, social and economic transformations occurring in these countries. Unfortunately, the opportunities of urbanization are lost due to lack of adequate resources, basic infrastructure, services and well-conceived planning [5]. Urbanization process in Africa has consequently been described as “pseudo-urbanization” [9]. It is in the light of this that this paper examines the urbanization phenomenon and its implications for low-income housing in Lagos, Nigeria. This has become necessary in view of the critical role housing plays in the life of an individual and society at large. Housing provides shelter for man and his belongings from inclement weather and intruders.

2. The Nature and Scope of Urbanisation

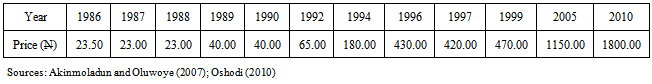

- Urbanization is a global phenomenon that has transformed and continues to alter landscapes and the ways in which societies function and develop [3]. Cities offer the lure of better employment, education, health care, and culture; and they contribute disproportionately to national economies [8]. Urbanization is one of the major demographic and economic phenomena in developing countries, with important consequences for economic development, energy use, and well being [2]. According to [10], definitions of “urban” vary from country to country. Basically, urbanization is the shift from a rural to an urban society, and involves an increase in the number of people in urban areas during a particular period [8], [2]. The United Nations Habitat in 2006 described it as the increased concentration of people in cities rather than in rural areas [11]. Urbanization is the outcome of social, economic and political developments that lead to urban concentration and growth of large cities, changes in land use and transformation from rural to metropolitan pattern of organization and governance. Urbanization also finds expression principally in outward expansion of the built-up area and conversion of prime agricultural lands into residential and industrial uses. This process usually occurs when a nation is still developing. The trend toward urbanization is a worldwide phenomenon, [2].According to [12], London was the major city of the world in the nineteenth century, being the first to reach the population of one million, a feat not attained by Paris until the mid-nineteenth century, New York until 1871, Berlin until 1880 and Vienna until 1885. Outside Europe the largest cities were Tokyo and Beijing. Today, the distribution of the world's largest cities is markedly different being dominated by cities in developing countries. UN (2012) revealed that by 2011 only three cities from the developed countries, namely Tokyo (37.2 million), New York (20.4 million) and Los Angeles (13.4 million) were among the world's top twenty cities. Lagos (11.2 million), Nigeria was ranked 19th. Literature suggests three features which distinguish the current trend of global urbanization. Firstly, it is taking place mainly in developing countries; secondly it is occurring rapidly and thirdly the severance of its occurrence and impact appear unevenly distributed across the globe, as [13] observed. Between 2011 and 2030, it is projected that the urban population of Ukraine will decline by 2 million and that of Bulgaria by 0.2 million [6]. Similarly, between 2030 and 2050, more countries like Japan, the Russian Federation, the Republic of Korea and Ukraine will experience varying degrees of reductions in their urban populations. Thus while many developed countries are either growing very slowly or are on the decline, populations of developing countries are growing rapidly [14]. The world urban population is expected to increase by 72 per cent by 2050, from 3.6 billion in 2011 to 6.3 billion in 2050. Virtually all of the expected growth in the world population will be concentrated in cities of developing countries whose population is projected to increase from 2.7 billion in 2011 to 5.1 billion in 2050 [6]. Lagos, Nigeria, for example is projected to have a population of 18.9 million which will place it as the 11th most populous city. This implies that most of the expected urban growth will actually take place in developing countries. Unfortunately, these are the countries that are ill-equipped to handle such enormous surge in population. Consequently, majority of the population increase will be accommodated via informal strategies. Amongst continents and even within a country or a city, urban growth is not uniform. Although the world has attained the 50% urbanization in 2007, Asia will achieve that feat by 2020, while Africa is likely to reach the 50 per cent urbanization rate benchmark in 2035 [6]. According to the 2011 Revision of the World Urbanization Prospects the urban areas of the world are expected to gain 1.4 billion people between 2011 and 2030, 37 per cent of which will come from China (276 million) and India (218 million). The report predicts that between 2030 and 2050 another 1.3 billion people will be added to the global urban population. With a total addition of 121 million people, Nigeria will be the second major contributor next to India (270 million). Together, these two countries are expected to account for 31 per cent of urban growth during 2030-2050 [6]. Such rapid growth of the population of the less developed regions, [10] combined with the near stagnation of the population in the more developed regions implies that the gap in the number of urban dwellers between the two will continue to increase [14]. This is evident in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Urban and Rural Populations by Development Group, 1950-2050. Source: UN (2012) |

2.1. Major Causes of Urbanization

- Several factors are responsible for urbanization. These include population dynamics, economic growth, legislative designation of new urban centers and increases in densities of rural trading centers. Early urbanization was attributed to the push and pull factors of rural-urban migration. Early migrants, usually males, went to the city in search of job and better life. Even in modern times, the lure of the city and the opportunities it should offer continue to be a major driving force of urbanization in many countries, [13], [15], [2]. In Africa, most people move into the urban areas because they are ‘pushed’ out by factors such as poverty, environmental degradation, religious strife, political persecution, food insecurity and lack of basic infrastructure and services in the rural areas or because they are ‘pulled’ into the urban areas by the advantages and opportunities of the city including education, electricity and water. Over the years, it has been argued that urban growth is attributable to natural growth, [13], [15], and [16]. [16] identifies demographic trends especially declining mortality rates in most developing countries which have not been matched by a corresponding decline in fertility. According to [15], research indicates that natural increase can be responsible for about 60% of urban population growth in some developing countries. While acknowledging that urban populations are still growing in sub-Saharan Africa, in many cases rapidly, [10] concurs that such growth is largely attributable to natural increase as births exceed deaths in towns, especially among the poorest sections of the population. The large-scale rural-urban migration required to generate sustained increases in urbanization levels has evaporated since the 1980s. On the contrary, [13] argues that “because rates of natural increase are generally slightly lower in urban than in rural areas, the principal reasons for rising levels of urbanization are rural–urban migration, the geographic expansion of urban areas through annexations, and the transformation and reclassification of rural villages into small urban settlements”. Natural increase is fuelled by improved medical care, better sanitation and improved food supplies, which reduce death rates and cause populations to grow. Data from various countries however strongly suggest that current urban population increase may after all be due to natural increase, [17]. The United Nations report asserts that many countries embarked on policies aimed at modifying the spatial distribution of their population by reducing migrant flows to large cities. Consequently, by 1976, 44% of developing countries reported implementation of such policies and by 2011, 72% of developing countries had put in place measures aimed at curbing rural-urban migration [17]. A third reason for urban growth is the reclassification of rural areas as urban or a change in the criteria for “urban” or annexation [13]. Over time, some rural areas accumulate sufficient population to qualify them to be classified as urban. In recent times the proportion of migrants to towns and cities who leave again – a phenomenon known as circular migration – has increased significantly [10]. Confronted by economic insecurity and other hardships worse than where they came from, [10] note that people behave as rationally in Africa as anywhere else. Rationality may therefore dictate relocation back to the rural area or even another urban area.

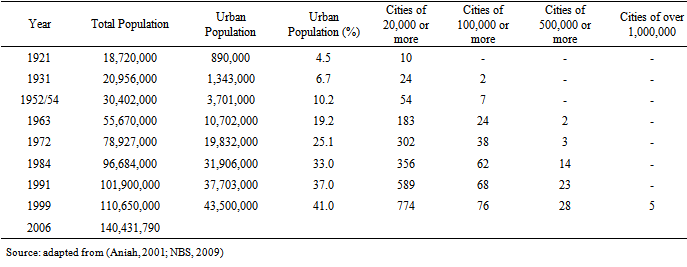

2.2. Overview of Urbanisation in Nigeria

- Available data on urbanization in Nigeria is largely conflicting (Gould 1995; Adepoju 1995; Oucho 1998). Abiodun (1997) opines that such data constrains effective discuss. UN-Habitat and the World Bank are the most frequently cited sources of urban population statistics. However, their data are sometimes misleading and appear exaggerated as opined by Potts (2012. In Nigeria, virtually every census since 1952 has been highly contested (Potts, 2012). This is perhaps due to both political and economic reasons. Economically, federal statutory allocation to states is influenced by their population. Thus states with reportedly low populations are disadvantaged in resource allocation from the federal level. Politically, in the democratic setting politics is a game of numbers and political parties controlling large population can be at an advantage. Population is also one of the indices upon which parliamentary representation is based. Despite the controversies, available data give sufficient indications of Nigeria’s urban status.

|

3. Method of the Study

- The bulk of data used for this paper was obtained from archival materials. This was complimented by observations and professional experience garnered in Lagos as both a researcher and teacher in the field of housing and urban development spanning almost three decades. The foregoing provided ample data needed to elucidate the salient features of urbanization in Lagos and how this has impacted on housing for the poor. Similar methodology has been adopted by Daramola and Ibem, (2010) and Ilesanmi, (2010).

4. The Study Setting

- With a total landmass of approximately 3,345 square kilometres, which represents almost 0.4% of the total land area of Nigeria, Lagos is the smallest state in the country [23], [34]. Lagos has a long history predating colonial period. It grew as a trade centre and seaport in the 15th century, [35]. However pre-colonial Lagos was mainly a fishing and farming settlement in the 17th century [36]. Owing to its physical characteristics, it became an important slave-exporting port in the eighteenth century [36]. With the advent of British colonial rule in West Africa, Lagos was among the pre-colonial cities that were favoured by the prevailing political and economic order [36]. From independence, Lagos was the capital of Nigeria [34] until 1991when the seat of federal government was moved to Abuja. It has however remained as the industrial and commercial hub of the country [37] and thus, attracts a good number of in-migrant and immigrant settlers. In addition to being the Federal Capital it was also a State in its own right, created on May 27, 1967 by virtue of the State Creation and Transitional Provisions of Decree No. 14 of 1967.

5. Growth of Lagos

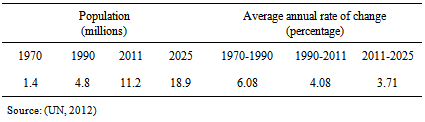

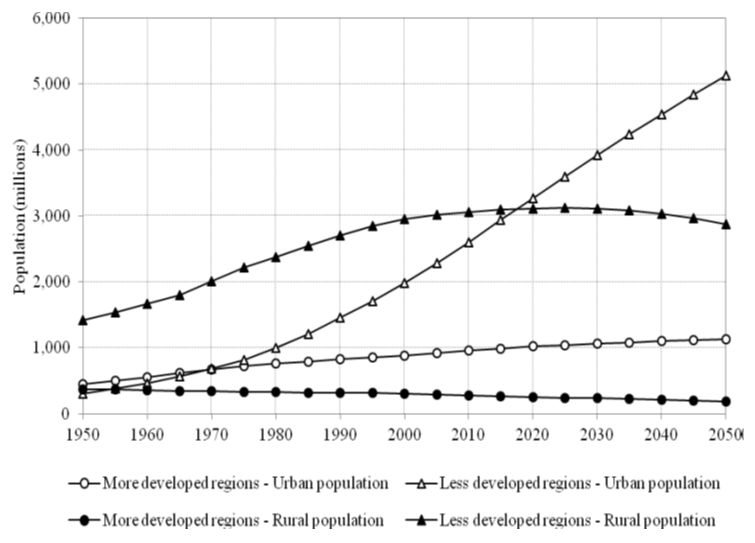

- Although controversies continue to trail Lagos population figures, there is a general concensus that population growth of Lagos has been very rapid [38], [39] and [39], [36], [40] and [41]. The city of Lagos has expanded dramatically since the colonial era, when it became the administrative headquarters of the country [23]. Expansion has not only been demographic but also spatial as frantic efforts are made to reclaim land from the ocean [36]. Figure 2 shows the growth of metropolitan Lagos between 1990 and 2000.The urban population in Lagos State grew from 267,400 in 1952 to 665,246 in 1963 at a rate of over 8.6% per annum [34]. United Nations statistics reveal that in 1995, Lagos became the world’s 29th largest urban agglomeration, with 6.5 million inhabitants and steadily moved up to the 23rd position in 2000 with 8.8 million people [4]. By 2002 Lagos metropolitan population had hit the 10 million population mark [4]. The World Urbanization Prospects 2011 Revision rated Lagos as the 19th most populous city in the world in 2011 with a population of 11.2million people and projected that by 2025, Lagos will overtake several other cities to become the 11th most populous city in the world with a population of 18.9 million [6]. Earlier predictions had indicated that the population of Lagos will rise to 16 million inhabitants by 2015 [4]. The population of Lagos and its average annual rate of change for the period between 1970 and 2025 are presented in Table 2.

| Figure 2. Growth of Lagos from 1900 to 2000. Source: Abiodun (1997) |

|

6. Urbanisation Challenges in Lagos

- As the pace of urbanization and urban growth proceed almost unabated in Lagos, the State government’s capacity to manage the consequences of undesirable urban trends decreased due to inadequate funding and institutional capacities [13], [7]. This is evident in poor services delivery, lack of adequate and affordable housing, proliferation of slums, chaotic traffic conditions, poverty, social polarization, crime, violence, unemployment and dwindling job opportunities [5]. The social, economic and environmental effects of these failures fall heavily on the poor, who are excluded from the benefits of urban prosperity.

6.1. Housing

- Construction of houses has not kept pace with urban rapidly expanding populations leading to severe overcrowding and congestion in slums. In some areas of Lagos, the cost of living has forced residents to live in low quality slums and shanty houses [2]. Slums are areas of concentrated disadvantage. Life in slums is characterized by serious problems of environmental pollution, lack of access to the basic social services, poverty, deprivation, crime, violence and general human insecurity and life-threatening risks and diseases [30], [11]. [43] reported that a 1981 World Bank assisted urban renewal project identified 42 “blighted areas” in the Lagos metropolis alone which over the years have risen to over 100 [44], [45]. Growth of slums has been attributed to public negligence and unabated population increase [34]. According to [21] 1.6 million new housing units were required between 1985 and 2000 and another 1.9 million units would be needed between 2000 and 2015. Thus a total of 3.5 million new units were estimated for the 1985-2015 period to adequately house Lagos residents. According to [44] and [46] the housing deficit in Lagos is currently estimated to be 5 million housing units representing 31% of the estimated national housing deficit of 18 million [44]. Consequently, the available few housing is expensive and unaffordable especially by poor households who are constrained to resort to informal housing procurement processes. Inability to afford better housing also force majority of residents to live in one room units. A 1970 Nigerian Government Urban Survey showed that 70% of the households in Lagos lived in one-room housing units [47]. By 2007, the figure had marginally risen to 72.3%, [48]. Percentage of Lagos households residing in one room however reduced to 68.1% the following year. This form of housing is depleting fast due to its unattractiveness to landlords in terms of economic gains and management challenges. The impact of rent control law recently introduced in the State is yet to be felt. It is expected to restrict the rent charged to tenants thereby allowing existing tenants to remain in place thus reducing resident turnover. In the past, such laws have been ineffective serving rather to reduce investment in building maintenance, construction of new housing. As deterioration of non-viable buildings continue, they fall into the hands of developers or higher income people who redevelop them to suit the tastes of higher income tenants. This process of property filtering known as gentrification has been reported in parts of Lagos by [34].

6.2. Demographic and Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Lagos Population

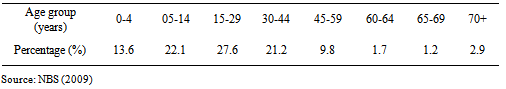

- It has been suggested that urbanisation is both a mirror of broad socio-economic changes in society and an instrument of socio-economic change. It affects societal organizations, the nature of work, demographic structures within and without the the family, people’s lifestyles and choices. The socio-economic characteristics statistics will assist in providing a better understanding of the likely patterns and trends of urban change [13]. Nigeria has a very young population [21]. Table 3 shows that 35.7% of the Lagos population falls below the age of 15 years while another 27.6% falls within the 15-29 years bracket. The master plan of Lagos was reportedly based on a projection of an average of 6.3 persons per household [21]. More recent data indicates that average household size appears to be on the decline from 4.28 persons/households in 2004 to 3.8 persons per households in 2008 [48]. This can be attributed to parents having fewer children on average as well as a gradual disintegration of the bonds which held members of the extended family together as nuclear family is gradually becoming the norm rather than the exception. In addition, due to the observed trend of career pursuit and late marriage, many young people are establishing homes which understandably are small in size. A reduced household size also implies more household formation and the need for more housing units. Constrained by availability and affordability, Lagos residents have gone into various housing sharing arrangements sometimes involving persons without any blood or marital relationship.

|

|

6.3. Living and Environmental Conditions

- Living conditions are worse among poor households living in the informal settlements with population density of about 20, 000 persons per square kilometre in the built-up areas, occupancy ratio of 8–10 persons per room and 72.5% of households living in one-room apartments [44]. In such settlements conditions are far from acceptable and constitute health hazard to the residents [50], [51]. By 2006, only 18.6% of Lagos households had access to treated water; 38.2% had flush toilets and 72.7% disposed refuse by unauthorized methods [48]. Serious overcrowding has also been observed with about four persons per room [34]. Overcrowding has adverse effects on sanitation and health, [52]. Low socio-economic status is known to be associated with a higher prevalence of major depression, substance abuse, and personality disorders Garbage and waste disposal problems in Lagos have aggravated long standing problems of seasonal flooding and sewage backup [32]. Land excavations and reclamation activities in parts of Lagos pose serious threat to the environment escalating incidences and severity of flooding. The problems of industrial pollution are enormous. Nigeria has about 5,000 registered industrial facilities and some 10,000 small scale industries operating illegally within residential premises [20]. Many of these are located in Lagos. They contribute to pollution through poor operational methods and waste management. According to the World Bank Report of 1990, the long term loss to Nigeria from environmental degradation was estimated to be about US$5 billion annually or the equivalent of the nation's annual budget [20].Due to its peculiar terrain, Lagos has been experiencing severe flooding. This has however been worsened by rising sea levels and other issues attributable to climate change. Urbanisation contributes significantly to climate change [14]. According to [15], rising sea levels due to global warming will take a heavy toll on cities because many are located on low ground close to the sea; 40% of the world's population lives within 65km (40 miles) of the sea. Lagos falls within this group. Lagos is essentially built on poorly drained marshlands [22]. Water is the most significant topographical feature in Lagos State, since water and wetlands cover more than 40% of the total land area within the State and an additional 12% is subject to seasonal flooding [23]. Poor people in developing countries are particularly vulnerable to floods, landslides, extreme weather and other natural disasters as they are more likely to live on dangerous floodplains, river banks, steep slopes and reclaimed land, and their housing is less likely to survive a major disaster [15].

7. Implications for Planning and Housing Development

- The urbanization trend in a city of the developing world like Lagos poses serious challenges for housing development. Housing is of significance because of its role in the socio-economic and political life of not only the individual but society at large. Some of these challenges are highlighted below:● Rapid population growth and changing demographic structure;● Poverty and unemployment;● Growth of slums and informal settlements; ● Lack of capacity on the part of government;● Difficulties in accessing housing delivery input (land, finance, building materials and labour); ● Prohibitive standards; and ● Environmental issues including climate change.These challenges have serious implications on the quality and quantity of housing demand in Lagos some of which are discussed below:

7.1. Rapid Population Growth and Changing Demographic Structure

- A closer look at the demographic data of Lagos reveals the following: a fast growing population; a predominantly young population; smaller household size; and preference for individualism. The combined implication of the above is the demand for more housing units to cater for the shelter needs of the resulting households. In doing this the current trend of smaller household size needs to be taken into consideration. However, it should also be noted that a household made up of predominantly young people will grow. Such young households are composed of young persons who are leaving parental homes to start off life on their own. The accommodation needs of such persons, especially when fund is scarce will normally be basic and compact. However with time they get settled and venture into marriage and child bearing. As their household size increase over the household lifecycle, more household space becomes needful. Thus while housing units may be initially small, changes over the household lifecycle demand for flexibility. Flexibility provides a household room to adjust as family circumstances and needs change over time. Inability to achieve this subjects a growing household to housing stress which can trigger mental and psychological disorders. On the alternative a household may be compelled to adjust to such stress by relocation to a more appropriate accommodation.

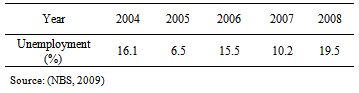

7.2. Poverty and Unemployment

- Government economic policies and programmes especially since the oil crisis of the 1980s have combined to erode the purchasing power of the average Nigerian. Not only has the national currency systematically been devalued, subsidies on basic items like fuel have been gradually removed and taxes and tariffs increased upward. Both public and private sectors have laid off some of their employees in a bid to reduce operational costs. Within the period, several industrial concerns have closed down while those still in business operate at levels far below their installed capacities. Lagos has a high proportion of both the unemployed and poor who come there with hopes of improving their conditions. This is because Lagos has remained the commercial capital of the country with more concentration of businesses than any other city in the country. Poverty and unemployment in the city has created and reinforced social exclusion.The UN Habitat [11] has cautioned that rising inequality in many parts of the world will generate tension and even conflict in cities and towns and therefore calls for social inclusion in cities like Lagos. Housing development especially for the poor has enormous capacity for redistribution of resources through creation of employment and income generation opportunities. These would normally be realized by utilizing opportunities created by the huge forward and backward linkages for which housing has been generally acclaimed. In addition, poverty raises the issue of affordability of housing whether for rental or owner-occupation. The current situation where residents spend up to 70% of their income on housing does not augour well for the social stability of the city. Inability to pay for accommodation has led to the incidence of homelessness and conversion of the under of fly-over-bridges for residence in Lagos. Such shelter is often made from recycled materials like cardboards, posters, nylon, zinc and even clothing.

7.3. Growth of Slums and Informal Settlements

- A major feature of the Lagos urban landscape is the proliferation of slums and informal settlements. These have evolved in response to government inability to provide adequate housing for the teeming population. These slums and informal settlements provide accommodation for majority of the people and are usually the first point of call for new migrants. However, they are urban manifestations of government neglect and lack. They evolve haphazardly on precarious locations prone to flooding, rising damp, building collapse, fire outbreak and epidemics [23]. Because of its limited landmass and difficult terrain characterized by marshy wetlands and high water table, suitable land for building is scarce in Lagos. Reclaimed land from ocean is usually beyond the reach of the poor. Building in difficult terrain requires careful planning as well as strict adherence to safety standards. The poor rarely comply with these. Proactive moves by government will curb the emergence of informal settlements. Such intervention will anticipate the directions of city growth and thereafter move in to plan the layout and provide basic infrastructure prior to people moving in. this way the chaos that is usually evident in informal settlements will be minimized. In addition, while government need not get involved in direct construction of houses, it should provide the guidelines for development and ensure compliance of the people through effective monitoring. Most of the houses in informal settlements are characterised by single storey house types depicting horizontal densification. Due to low floor area ratios in the emerging house types the capacity of the government authorities to efficiently and effectively supply needed services is further constrained.

7.4. Lack of Capacity on the Part of Government

- Political will is crucial to any government programme aimed at improving the living standard and quality of life of the people. To be able to provide the regulatory structure needed for housing, government capacity ought to be enhanced technically and morally. The number of qualified staff in Lagos is grossly inadequate to cope with the magnitude of housing development envisaged in the city. Tempo of current manpower development drive in the State should be increased to meet up with demand. Corruption is a worrisome cankerworm of the Nigerian society. However, it must not be allowed to mar professionalism and integrity.

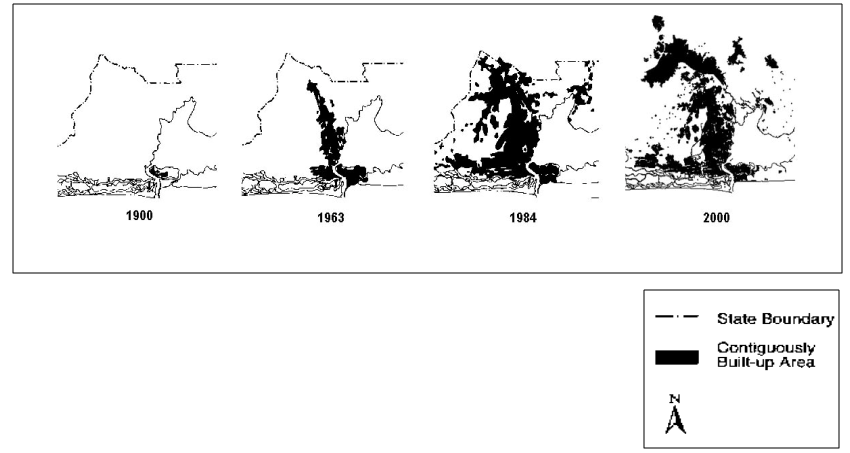

7.5. Difficulties in Accessing Housing Delivery Inputs

- As a result of the high cost of renting accommodation and the idiosyncrasies of shylock landlords, the average urban resident in Nigeria prefers to own his residence. This preference is observed to be very strong among Lagos residents. [53] has observed several other benefits of homeownership which include: creation of greater stability in the community, reduction of the tendency to vandalism and violent protests, enhancement of patriotic ardour and love for one’s home and community as well as facilitating the process of civic engagement with the affairs of the community and local government. Nonetheless, [44] found that about 60% of residents are tenants and have to pay rent as high as 50-70% of their monthly incomes. Thus access to decent housing whether on rental or owner-occupier basis has however remained a fleeting dream for many Lagos residents. This is mainly attributable to the difficulties encountered in accessing vital housing inputs like land, finance, building materials and labour. In spite of reforms in the housing finance sector which led to the establishment of the National Housing Fund in 1992, strengthening of the Federal Mortgage Bank and the formation of Primary Mortgage Institutions (PMIs) to advance and manage loans to contributors, housing finance remains a key bottle neck to housing delivery in Nigeria [49], [52]. According to [44] as at December, 2010, a total sum of N50.68 billion was approved out of which N23.89 billion representing 47% was disbursed to 16, 468 applicants through 57 PMIs. The average amount approved is equivalent to N1, 450, 692 (US$9, 359) per beneficiary. Significant numbers of Nigerians who are mainly in the informal sector of the economy were denied participation from this scheme because of low deposit mobilization, inability to track their monthly income and lack of formal titles to their land holdings. Mortgage financing and mortgage-backed securities exist in Nigeria at the moment in the rudimentary state at best. At present, a typical home buyer will have to make a down payment that range between 20 to 50% of the purchase price and then pay off the loan balance within 5 years. The problem of inadequate housing for the citizens in Lagos is further aggravated by the declining budgetary allocation for housing by the government. [44] found that in 2000, N667 million representing 4.05% of Lagos State budget was earmarked for housing while N776 million representing 1.42% was budgeted in 2005. Of N224.6 billion total budget for the year 2010, only N6 billion representing 2.7% was earmarked for housing. Owing to rapid urbanisation, access to land for housing development has become an almost insurmountable challenge. Land prices have been rising extraordinarily in the urban areas since the 1970s’ occasioned by the oil boom then and high rates of demand due to explosive urbanization. In recent years, the price of land has risen exponentially, making it unaffordable to many low and middle-income earners. Land is a major component in housing provision and delivery. Without land, houses cannot be built. Due to high cost of land, the urban poor are pushed to inaccessible locations for land, areas prone to disasters (steep slopes, rocky areas, too close to river channels, etc), and engage in minute subdivision of land and building below minimum standards. The problem of affordable housing in Nigeria is further exacerbated by the constraints imposed by the Land Use Act, a moribund and repressive Act that hinders mortgage financing and creates enormous obstacles to private sector involvement in the housing industry and which has constrained the transfer of titles and made mortgage finance extremely difficult. As a result of the Land Use Act, obtaining a Certificate of Occupancy (popularly known as C of O) has become a big time avenue for large scale corruption. Other constraints with land administration identified by [54] include regulatory and planning controls for building and construction that constrain the efficient utilization of the land, as well as high inflation rates in the Nigerian economy. These distortions are further exacerbated in Lagos by the city’s limited land supply and immense population density. Consequently, land speculation is very high. Similarly, fraudulent land transactions whereby a piece of land is sold to multiple unsuspecting buyers by unscroupolous land owners called 'omo oniles' is becoming increasingly rampantas reported by [34]. As suggested by [2006] reforms in land, capital and labour markets must be expedited to increase the inflow of capital from institutional sources and private sector. The rising cost of building materials has negatively affected urban development projects and the construction of housing. [44] reported that the rate of price increase for sharp sand between 1997 and 2005 ranged from N2,300 to N12,000. Price hike for an essential material in housing construction like cement rose from N23.50 per bag in 1986, N420 in 1997, N1, 150 in 2005 to N1, 800 in 2010, as shown in Table 5. During the same period, [44] found that the purchasing power of average resident in Lagos have declined with non commensurate income wage and commitment of over 40% of income to housing expenditure against the United Nations recommended 20%. Building materials used in the country are mainly imported at the expense of scarce foreign exchange. They are thus subject to inflationary trends in the economy. Of the over 11 million metric tonnes of cement required yearly in Nigeria, less than 50% is produced locally while the rest is imported. Prevalence of imported building materials can be attributed to the average Nigerian taste for imported materials and the lack of indigenous capacity to produce the needed quantity of materials. Besides, lending institutions would normally consider houses constructed of local materials as bad business either in the case of applying for loan to build the house or using such a house as collateral.

|

8. Recommendations

- The extent of the housing shortage in Lagos is enormous. The inadequacies are far-reaching and the deficit is both quantitative and qualitative. Urgent multi-faceted intervention is needed to address the situation since housing is affected by policies in other sectors.

8.1. Planning and Regulatory Framework

- Planning should be proactive and backed by reliable data. State agencies responsible for establishing new towns should open up new areas serviced with relevant infrastructure in order to tackle the growth of informal settlements. In selecting locations, precarious sites prone to natural disasters like floods should be avoided while effective strategies aimed at combating the possible dangers posed by climate change are also taken into account. In order to make the plots affordable to poor households, mixed developments catering for all income groups are advocated where profits made from the medium and high income groups would be used to subsidise the cost of low-income plots. Differential standards in plot size will also help to make plots affordable to the poor. Generally, while standards should aim at ensuring safety and sound construction, it should not restrict the potential opportunities of the poor to generate income within their neighbourhoods.

8.2. Finance

- Hitherto, majority of households have relied on their savings to access housing due to the weaknesses of the Nigerian housing market. The National Housing Fund which was expected to facilitate easy access to mortgage has proved to be a huge disappointment. There is a need to reorganize the National Housing Fund in order to make it more responsive to the needs of the people. Banks and other financial institutions should be mandated to set aside a percentage of their loanable funds to low-income households. Such directives should be monitored to ensure compliance.

8.3. Building Materials

- In order to address the issue of availability and affordability of building materials, concerted effort should be made at encouraging use of local building materials. Although this has been incorporated into the National Housing Policy, it has not yet been sufficiently translated to reality. Aside from enormous savings from foreign exchange, use of local building materials will enhance the indigenous technological base of the country. Government support for the cottage production of local building materials, components, fixtures, and fittings will reduce cost of housing construction while creating employment and income generation opportunities for urban residents. Small neighbourhood workshops often have cost advantages because of the low cost of transportation from the production centre or workshop to the building site. Such production centres and workshops can be established on co-operative basis and also serve as display and skill acquisition centres. To facilitate the use of such materials, appropriate standards should also be formulated for them.

8.4. Building Designs and Construction

- Several of the housing quality issues experienced in housing can be attributed to lack of use of adequately trained professionals generally known as quacks. Currently, draughtsmen who fall into this group are allowed to design certain categories of buildings. Such practice should not be encouraged. Activities of quacks have contributed significantly to the growth of slums in Lagos. Building designs and construction should take into account climatic, environmental and socio-economic characteristics of the people in order to ensure safety, comfort, affordability and livability among others.

9. Conclusions

- Urbanization is a inevitable process which unfortunately was not anticipated and planned for. The challenges posed by urbanization in a city like Lagos are many but not insurmountable. Tackling such challenges will require good knowledge of the characteristics of the people accessing the city as well as accurate projections of future urban growth. While housing should not be treated in isolation, sustained effort including adequate budgetary allocations and strengthening of relevant agencies are required to address the protracted housing challenge.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML