-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Zoology

p-ISSN: 2325-002X e-ISSN: 2325-0038

2012; 2(5): 38-46

doi: 10.5923/j.zoology.20120205.01

Diversity and Abundance of Butterfly Species in the Abiriw and Odumante Sacred Groves in the Eastern Region of Ghana

Beatrice T. Nganso1, Rosina Kyerematen2, Daniel Obeng-Ofori3

1African Regional Postgraduate Programme in Insect Science (ARPPIS), University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, P. O. Box LG PMBL59, Ghana

2Department of Animal Biology and Conservation Science, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, P. O. Box LG 67, Ghana

3College of Agriculture and Consumer Science, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, P. O. Box LG PMB L 68, Ghana

Correspondence to: Beatrice T. Nganso, African Regional Postgraduate Programme in Insect Science (ARPPIS), University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, P. O. Box LG PMBL59, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Sacred groves in Ghana have been adopted as one of the strategies to mitigate the loss of biodiversity. They are seriously under threat from anthropogenic activities. A six month survey of the butterfly fauna in the Abiriw and Odumante sacred groves in the Akwapim North and South Districts, respectively of the Eastern Region of Ghana was conducted to characterize resident butterfly species diversity and abundance. The transect count method and charaxes traps were used to sample the butterflies. Analysis of butterfly diversity in these groves, which range in size from 400 m2 to 250 m2, was used to evaluate their effectiveness in achieving conservation objectives. Community diversity was characterized in terms of, (a) number of species accumulated versus sampling effort, (b) nonparametric richness estimates, (c) Simpson’s and Shannon-Weiner Indices of Diversity, and (d) Complementarity of communities. A total of 1169 individual butterflies were trapped across all sites representing 89 species from 10 families. Butterfly species richness and evenness in the Abiriw grove was higher than that of the Odumante grove, however, the Abiriw grove harboured a resident community that was not distinctive from the Odumante grove. These findings add to the body of knowledge that indicates that large groves are the foundation of successful conservation programs. Nonetheless, it was observed that both groves harbour a number of species that appear vulnerable to dynamics of forest fragmentation based on changes in their relative abundance across sites. The findings are discussed in the context of potential indicator species and theoretical predictions of at-risk species.

Keywords: Butterfly Diversity, Sacred Grove, Fragmentation, Protected Areas

Cite this paper: Beatrice T. Nganso, Rosina Kyerematen, Daniel Obeng-Ofori, "Diversity and Abundance of Butterfly Species in the Abiriw and Odumante Sacred Groves in the Eastern Region of Ghana", Research in Zoology, Vol. 2 No. 5, 2012, pp. 38-46. doi: 10.5923/j.zoology.20120205.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Sacred groves sometimes referred to as sacred forests around the world represent a traditional form of community-based conservation. Throughout the ages, they have been protected for several generations for a variety of reasons including religious practices or ceremonies, as burial grounds and for their watershed value[1, 2]. These community-protected forests are often associated with traditional regulations or rules such as taboos, totems and myths that deter human exploitation within the groves. These complex traditional rules have long preserved the integrity of sacred forests and appear to have a crucial conservation role in maintaining biodiversity in sacred groves. There are an estimated 2,000–3,200 sacred groves in Ghana, about 80% of which occur in the southern half of the country[3]. They ranged in size from hundreds of hectares of forest to small areas of about 0.5 ha containing single trees or a few stones[3]. Sacred groves in Ghana were once part of continuous forest cover, but now mostly exist as relict forest patches embedded in an agro-pastoral landscape[4]. In some regions in the country, sacred groves also represent the only remaining examples of old growth forest vegetation harbouring rare, endemic and/or endangered species[5]. It is in this context that these indigenous forests can be used to guide reforestation or ecosystems recovery efforts in a landscape increasingly devoid of forested areas outside the existing protected area network. Ghana’s sacred groves have also been adopted as one of the in situ strategies to mitigate the loss of biodiversity[6]. Despite their high conservation value, Ghana’s sacred groves have been completely destroyed and/or reduced in size[7]. This situation could be attributed to (i) rapid population growth and its attendant problems of urbanization, migration, and resettlement, (ii) increased dependence on western technology, and (iii) the growing influence of foreign religions and beliefs[8]. In an attempt to conserve these indigenous fetish forests,[9] outlined a management strategy for Ghana’s sacred groves that advocates the following: (i)Legislation to reinforce the traditional regulations regarding use and access; (ii) Provision of resources to improve local people's capability to manage their groves; and (iii) Nationwide inventory of the groves and the biological resources they contain. Concerning the nationwide inventory of biological resources within sacred groves, most surveyshave focused on their botanical, ethno-botanical or socio-cultural functions[10, 11]. Few attempts have been made in the country to assess the diversity of insects in sacred groves. Comprehensive and long term studies are needed to assess the diversity of insects in all sacred groves in Ghana in order to better understand their crucial role in in situ conservation of biodiversity. The present study was therefore undertaken to assess the extent to which some sacred forests may contribute to the conservation of the country’s forest-butterfly species. To this end, a comparative analysis of butterfly community structure of the Abiriw and Odumante sacred groves in the Eastern Region of Ghana was conducted to assess their relative similarities and dissimilarities. The focus of this study was on isolated forest fragments in the Moist Semi-Deciduous Forest Zone of Ghana, the region of the country where remaining forests are most imminently imperilled.A focal group of insect, the butterfly species, was used to quantify two aspects of community diversity, species richness and species composition, in the two forest fragments. Butterflies have been beneficially exploited in studying numerous aspects of tropical forest ecology in natural, managed and degraded ecosystems. This is largely because member species show a diversity of relative sensitivities to environmental change, and they are tightly intertwined with ecological systems as both primary consumers (herbivores) and as food items. An assessment of the abundance and diversity of butterfly species in sacred groves can therefore indicate the role of sacred groves in biodiversity conservation, and also serve as a goodindication of the health of the environment in and around the groves.

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Study Sites

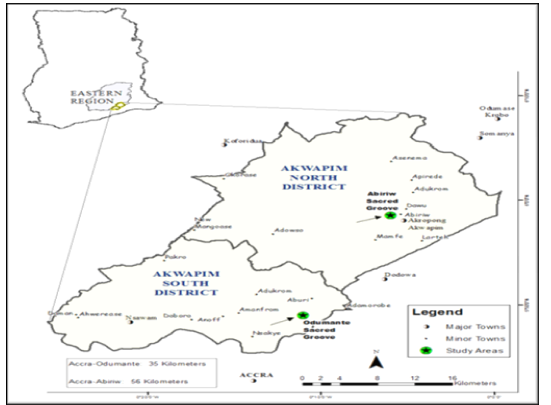

- The forests of Ghana comprise four increasingly dry vegetation zones. These are arranged as concentric bands, beginning with the Wet Evergreen Forests in the southwestern corner of the country, extending outward through the Moist Evergreen, Moist Semi-Deciduous, and Dry Semi-Deciduous Forest Zones[12]. The study was conducted in two isolated forest fragments namely Abiriw (05° - 48’ N; 00° - 06’ W) and Odumante (08° - 82’ N; 00° - 02’ W) groves both located in the Moist Semi-Deciduous Forest Zone of Ghana.. The Abiriw and Odumante groves are located in the Akwapim North and South Districts respectively of the Eastern Region of Ghana (Figure 1). The sacred groves range in size from 400 m2 to 250 m2. Individual sacred groves fall under the jurisdiction of local traditional councils, and permission from village elders to enter and collect from each grove was required and secured. The Abiriw sacred grove is a gazette reserve called the Bosompra Forest Protected Area; meanwhile the Odumante grove is a long protected sacred grove. Each sacred grove is completely surrounded by an anthropogenically derived farm bush savannah matrix. The Abiriw grove contains the Bosompra stream, which is the main water body draining the Abiriw township. Due to laxity in enforcing some of the customary laws that deter human exploitation of the forest resources, there has been increasing over-exploitation of these resources (e.g. logging, fuel wood harvesting, farming etc.) in the Abiriw grove. The Odumante grove has been well preserved for several generations however, due to the economic constraints that local communities are facing, the grove is exploited for fuel wood, used as a burial ground by local people and a site for acting of local movies.

2.2. Sampling Methods

- Typical fruit-baited charaxes traps and transect walk-and-counts were used to sample butterflies. One transect of 250 m was established from the edge of the forest to the forest interior and 5 charaxes traps were hung in each sacred site. Individual traps within areas were separated from each other by at least 50 m and by no more than 250 m. Conscious effort was made to set up all traps in similar micro habitats within areas of closed canopy forest. Sampling was carried out monthly during the rainy season (June, July and October) and dry season (December, January and February). Sampling was done during these months based on the availability of local field guides in the respective sacred sites. Sampling at a given site consisted of baiting the charaxes traps with mashed, fermenting or rotting banana with beer and retrieving trap collections after 4 days. At each site, one transect route and edges of the sacred grove were walked to sample butterflies. Sampling was done under sunny conditions mostly between 9:00 am and 4:00 pm. All butterflies seen within 2.5 m on either side of the transect route and edge of sacred grove and up to 5 m in front of the observer were recorded[13]. For those that could not be identified on the spot, photographs were taken with a digital camera for later identification.

2.3. Species Handling and Identification

- Standard field handling of specimens captured from charaxes traps consisted of firmly squeezing the thorax to disable the specimen[14]. The specimens were placed in glassine envelopes and stored for subsequent laboratory processing comprising identification, drying, spreading, pinning, photographing and labelling. Each processed specimen was labelled with a unique code that describes the exact place and date of collection. Butterflies collected were identified to the species level using a variety of taxonomic treatises, including[15],[16], and[17]. Difficult specimens were identified in consultation with Mr. A. R. Sigismund, an expert on insects and butterfly identification in Ghana.

| Figure 1. Map showing Abiriw and Odumante Sacred Groves in the Akwapim North and South Districts in the Eastern Region of Ghana |

2.4. Data Analysis

- Data from the two sources (fruit-baited charaxes traps and transect walk-and-counts) were pooled to obtain total butterfly diversity per study sites and per sampling period. The Student t-test was used to test the significant variation in the number of butterflies per family between sites, the total butterfly abundances between sites and between the wet and dry season in each grove[16]. For each site, the overall species accumulation curve was generated using the EstimateS program, Version 8.0[18]. The number of samples was used as the index of sampling effort. EstimateS was also used to compute richness estimates based on a variety of nonparametric estimators such as: e.g. Chao1, Chao2, ICE (Incidence-based Coverage Estimator), ACE (Abundance-based Coverage Estimator), Jackknife 1 and Jackknife 2 for Abiriw and Odumante sacred groves. The Margalef, Shannon-Weiner and Simpson species richness and diversity indices were computed for each site and for the wet and dry season in each site. The similarity or complementarity between sites and the wet and dry season in each site based on the number of shared species among the butterfly fauna was measured using the Morisita–Horn index (MHSij) and the Bray–Curtis index (Sjk)[19]. The computation was carried out using the EstimateS program.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Butterfly Abundance in the Respective Sacred Groves

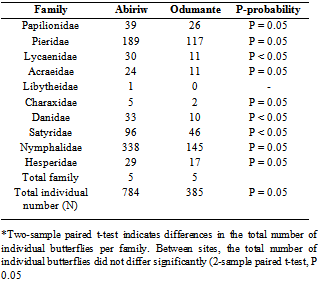

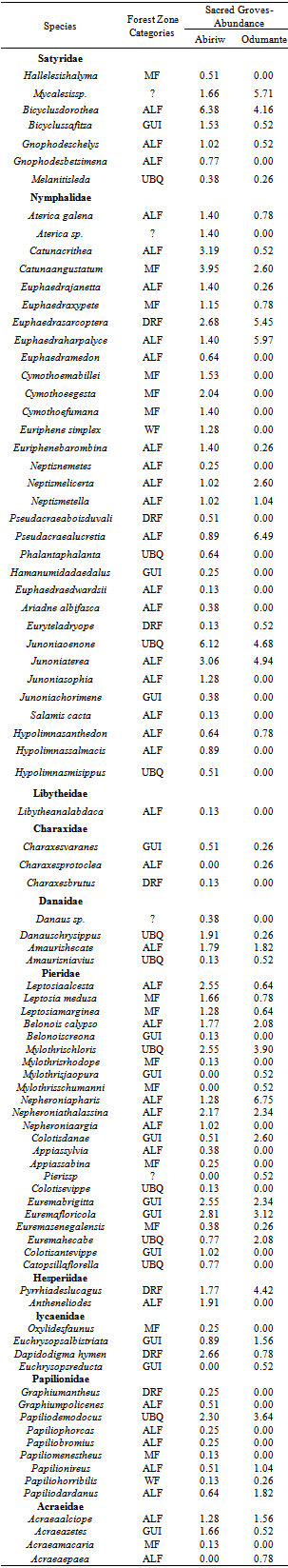

- Each site was sampled 6 times throughout the course of the study, resulting in a total of 1169 individuals captured across all sites combined. Eighty nine species were collected in total from all sites combined, belonging to ten families (Appendix 1). All but nine of the 89 species collected (Papiliodemodocus, Catopsiliaflorella, Euremahecabe, Mylothrischloris, Danauschrysippus, Amaurisniavius, Melanitis Leda, Hypolimnasmisippus and Junoniaoenone) are comfortable in closed forest in good condition[20]. Five butterfly species (Bicyclussafitza, Melanitisleda, M. libya, Ypthimomorphaitonia, and Charaxes varanes), which are endemic to the forest habitat were collected in four sacred groves and two forest reserves during a year-long survey of fruit-feeding butterfly conducted by[4] in Kumasi, Ashanti Region of Ghana. Three of these species (Bicyclussafitza, Melanitisleda and Charaxes varanes) were trapped in the Abiriw and Odumante sacred groves. All but thirteen of the 89 species are specialized on savannah habitat (Appendix 1). Greater than 60 % of those collected are considered either moist forest specialists or species found in all forest subtypes, which is as expected given the location of our study sites well within the Moist Semi-Deciduous Forest Zone. In both sacred groves, the two families that recorded the highest butterfly abundance and richness were the Nymphalidae and Pieridae families (Table 1). Our study represents the first comprehensive butterfly survey in the Odumante grove. Although butterfly survey has been conducted in the Abiriw grove in the past, butterfly species and numbers recorded were lower than that for this study.[20] recorded 207 individuals belonging to 51 species from 8 families during a 2-day collection with no Lycaenidae and Riodinidae recorded. Only one charaxes species (Charaxesprotoclea) was recorded. The relatively low species richness recorded during Boafo’s survey is consistent with theoretical expectation of short term insect’s inventory, whereby rapid assessment tends to be biased toward common well known species[21]. The rapid survey might have missed important rare species, which in ecological studies are very important from the conservation viewpoint. It can therefore be deduced that, our study represents the first comprehensive and long term butterfly survey in the Abiriw grove because more species were recorded with increasing sampling effort.

|

3.2. Observed Species Richness

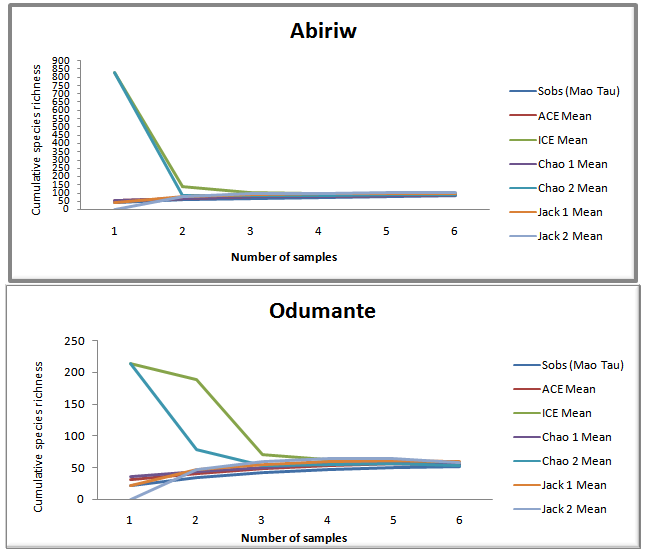

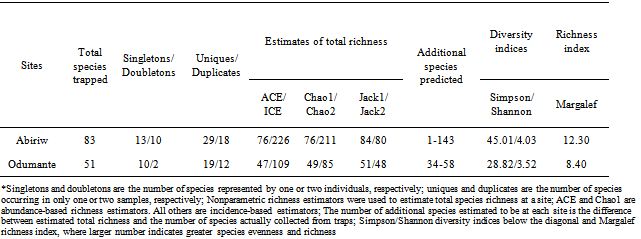

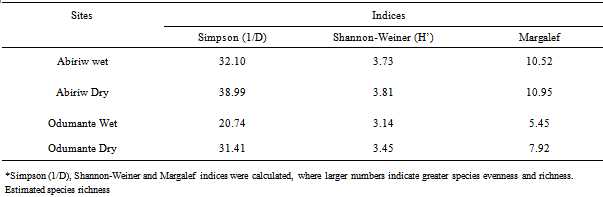

- The observed species richness was higher in the Abiriw grove than the Odumante grove, indicating that the butterfly community at Abiriw is generally more specious than that at Odumante (Figure 2; Table 2).This is consistent with theoretical expectation of species-area relationship, whereby small areas tend to support fewer species[22, 23]. Not surprisingly, the Margalef index of species richness was higher in the 400 m2 Abiriw grove than the 250 m2 Odumante grove (Table 2). The Abiriw community had a relatively higher abundance. In communities such as Odumante that are dominated by a few very abundant species, the vast majority of individuals in the community will be of these few predominant species, whereas in communities such as Abiriw where species are equitably represented, randomly encountered individuals are more likely to be derived from different species, which according to[24] is a defining characteristic of a diverse community. This is corroborated by the higher Simpson and Shannon indices of diversity at Abiriw than Odumante. These findings add to the already substantial body of data that indicate the primary success of biodiversity conservation hinges on protection of large habitat areas. At both sites, the species accumulation curves were clearly approaching an asymptote, indicating that species saturation had been reached and sampling effort was adequate (Figure 2). The Abiriw grove has retained much of its closed canopy as compare to the Odumante grove most probably due to its distance from the Abiriw village proper as well as its rural setting which may have probably helped preserve the grove’s integrity and resident biodiversity. Abiriw, unfortunately, also proved to be imperilled due to laxity in enforcing some of the customary laws that deterred human exploitation of the forest resources in the past. Before the beginning of the dry season collection, local communities cleared the route along which sampling at the grove was done, uprooting virtually every old growth and trees during the festival ceremony. This could be one of the possible explanations for the fewer number of individual butterflies collected during the dry season as compared to the wet season. Again, this event stands as a clear testimony to the enhanced vulnerability of small isolated forests to further degradation[25]. The landscape matrix surrounding the Odumante grove is uniquely characterized by intensive residential and farming activities adjacent to, and in some cases within the premises of the grove. The grove is also used as a burial ground by the local communities and as a site for acting local movies. All of these activities have undoubtedly led to the degradation or disruption of key ecological processes in the groves. This highly transformed landscape matrix has most likely served to hinder emigration from and immigration of butterflies to this isolated forest.In both sacred groves, butterflies were more specious and diverse in the dry season than the wet season (Table 3). Not surprisingly, the Margalef, Shannon and Simpson indices were higher in the dry season than the wet season (Table 3). As noted by several researchers[16, 17, 26], many butterfly species may increase if summer temperature increases. During the survey, the temperature was generally high during the dry season, reaching 32℃ as compared to the wet season, where temperature was generally below 24℃ (Conste, 2012 Personal communication). However, it should be noted that other factors such as resource availability for adults and larval host-plants, behavioural traits and interaction with other species may explain this increase in butterfly richness and diversity during the dry season[27]. This underscores the importance of measuring and documenting local conditions on determining species composition studies, even though these factors were not adequately measured in our study.

|

|

3.3. Estimated Species Richness

- The observed number of species in any sample of individuals from a community underestimates the true number of species present. In statistical terms, observed species richness (Sobs) is a biased estimator of the true richness for the assemblage sampled. Thus, a critical element of evaluating the performance of a species richness estimator is to assess how non-parametric richness estimators behave as a function of the number of samples[28]. These estimators helped in comparing the sampling effort and species realized to the estimated species richness.At both sites, the observed species richness clearly underestimated the true species richness. The ICE (Incidence-based Coverage estimator) and Chao2 (Incidence-based estimator) were the only estimators that tended to level off with increasing sample size and produced stable and broadly accurate estimates at small numbers of samples (Table 2). In several studies that attempted to evaluate the performance of nonparametric estimators, ICE and Chao2 have been reported to be the estimators that give promising estimate of the total species richness because they perform well at small sample size and are relatively insensitive to sample density and species patchiness[19, 29]. Other estimators tested fail to depict the true species richness. The Chao1 and ACE estimators, for example, used abundance data and in this study underestimated the true species richness because they were many unique butterfly species than singleton butterfly species in the assemblage sampled (Table 2)[30]. The Jackknife1 estimator performed better than the Jackknife2, especially at low sample sizes (Figure 2) when comparing the estimators in term of the ability to underestimate or overestimate (Bias) the true species richness. Earlier on,[31] reported similar result in their parasitological study in the United Kingdom. It therefore appears that Jackknife1 is a less bias estimator than Jackknife2 even though little consensus on estimator variability has arisen from a broad collection of estimator performance studies. At Abiriw, the estimators predicted 1-143 additional species, while that for Odumante; predicted 34-58 additional species (Table 2). Abiriw was thus predicted to have a more species rich butterfly community than Odumante.

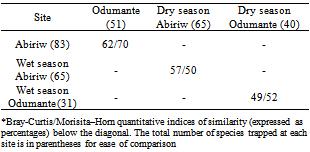

3.4. Site Complementarity

- A number of species were trapped at only one site (Appendix 1). Abiriw had, by far, the largest number of these at 38, most of which were fairly well represented. Six species were exclusive to the Odumante grove but nearly all of these were represented by two individuals. The butterfly community at Abiriw and Odumante were closely similar (Table 4). Within the Abiriw grove, the Bray-Curtis index indicated greater community similarity than the Morisita-Horn index when the wet and dry season communities were compared, meanwhile, within the Odumante grove; the Morisita-Horn index indicated greater community similarity than the Bray-Curtis index. In both sacred groves, the butterfly communities trapped during the wet and dry seasons were closely similar.

|

4. Conclusions

- Our preliminary assessment of butterfly diversity in habitat patches adds to the burgeoning evidence that sacred groves are potential storehouses of biodiversity in transformed landscape[34, 35]. These small forest patches are able to support resident populations of Charaxes sp., which are known as large and robust butterflies. In addition, a number of forest species endemic to the entire forest area West of the Dahomey Gap and West Africa (Papiliohorribilis, Hallelesishalyma, Euphaedra simplex and Pyrrhiadeslucagus respectively) were collected from the sacred groves. Thus, these relict forests are serving to foster persistence of forest species across a landscape matrix that is largely devoid of forest habitat. It is evident that sacred groves would not replace large forest reserves due to their relative smaller sizes. Rather, they could be a supplementary to forest reserves thereby enhancing more efficiently in situ biodiversity conservation in Ghana. The traditional regulations or rules which previously prevented people from exploiting forest resources from the groves, however, appear to have been relaxed, resulting in general grove degradation. Despite the cultural and biological significance of Ghana’s sacred sites, few receive active protection. Many have been completely destroyed and many others are under imminent threat by encroaching farms and residential development. Local communities are facing economic challenges posed by the modern world, and are therefore compiled to encroach the resources found within the groves. We, therefore, strongly recommend that an integrated approach to sacred grove management should be adopted in Ghana. This must take into account locals to serve as guardians within the framework of social forest conservation, private and cooperate organizations to help alleviate poverty in the local communities, scientific documentation of biological resources within the groves in different regions, campaigns and educational programmes highlighting the ecological and spiritual benefits of the forests for human sustenance, and a strong legislation to reinforce the traditional regulations regarding the use and access to sacred groves.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors are very grateful to the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) who funded the graduate research of TchuidjangNganso Beatrice at the African Regional Postgraduate Programme in Insect Science (ARPPIS), University of Ghana, Legon. We are also thankful to Mr. A. R. Sigismund for willingly offering and providing his expertise on butterfly identification and on multiple of other issues concerning general butterfly information in Ghana. We are extremely indebted to the Chiefs and Elders of Akropong and Ketase, who granted access to the sacred groves. A number of different people provided invaluable help in trap installation at both study sites.

|

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML