-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Tourism Management

p-ISSN: 2326-0637 e-ISSN: 2326-0645

2022; 11(1): 7-18

doi:10.5923/j.tourism.20221101.02

Received: Aug. 23, 2022; Accepted: Sep. 7, 2022; Published: Oct. 12, 2022

Perception of Branding Multiple Birth for Heritage Tourism in Igbo-Ora, Oyo State, Nigeria

T. G. Yusuf1, Tsado M. N.2, Haruna Z. A. B.3, Odusanya T. A.4

1Department of Family, Nutrition and Consumer Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile – Ife, Nigeria

2Department of Hospitality Management, Federal Polytechnics, Bida, Niger State, Nigeria

3Department of Hospitality Management, Kwara State Polytechnics, Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria

4Department of Hospitality Management, Federal Polytechnics, Ilaro, Ogun State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: T. G. Yusuf, Department of Family, Nutrition and Consumer Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile – Ife, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

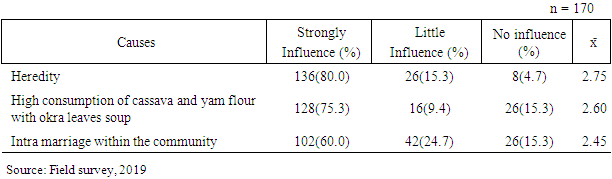

This study examined residents’ perception of branding multiple birth for heritage tourism in IgboOra, Oyo State, Nigeria. Primary data were gathered via questionnaire, key informant interview and observation. Secondary data were gathered from the records of the government general hospital, Igbo-Ora. Respondents numbering 170, who were selected by simple random sampling technique participated in the study. The study established that there is a record of twin birth in almost every family. The study also established that the residents associated high rate of multiple birth to heredity ( = 2.75), high consumption of indigenous yam and cassava flour and Okra leaves soup (

= 2.75), high consumption of indigenous yam and cassava flour and Okra leaves soup ( = 2.60) and intra marriage within the community (

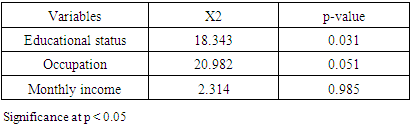

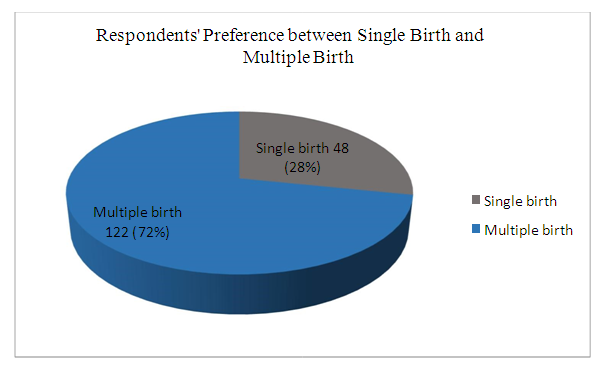

= 2.60) and intra marriage within the community ( = 2.45). The research showed that majority of the respondents (72%) prefer multiple birth to singleton birth, and have a positive perception towards branding multiple birth for heritage tourism. Chi-square analysis revealed a significant relationship between the residents’ educational status (X2 = 18.34; p < 0.05) and perception of multiple birth for tourism development. The study concluded that multiple birth is predominant in Igbo-Ora but yet to be tapped for tourism, hence, stakeholders should collaborate and package multiple birth for sustainable heritage tourism.

= 2.45). The research showed that majority of the respondents (72%) prefer multiple birth to singleton birth, and have a positive perception towards branding multiple birth for heritage tourism. Chi-square analysis revealed a significant relationship between the residents’ educational status (X2 = 18.34; p < 0.05) and perception of multiple birth for tourism development. The study concluded that multiple birth is predominant in Igbo-Ora but yet to be tapped for tourism, hence, stakeholders should collaborate and package multiple birth for sustainable heritage tourism.

Keywords: Multiple Birth, Igbo-Ora, Heritage Tourism, Sustainability, Development

Cite this paper: T. G. Yusuf, Tsado M. N., Haruna Z. A. B., Odusanya T. A., Perception of Branding Multiple Birth for Heritage Tourism in Igbo-Ora, Oyo State, Nigeria, American Journal of Tourism Management, Vol. 11 No. 1, 2022, pp. 7-18. doi: 10.5923/j.tourism.20221101.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Multiple gestation is a pregnancy where more than one fetus develops simultaneously in the womb. Depending on the number of developing fetuses, one can distinguish twin, triplet, quadruplet, or quintuplet pregnancy, and so forth. Scientists and non-scientists alike are fascinated by twins. Twin speak to us about the uniqueness and the natural bond between siblings. Dizygotic (DZ, nonidentical) twinning rates vary widely across different regions in the world. With a DZ twinning rate of 45 per 1000 live births, Igbo-Ora Community in South-west Nigeria has the highest dizygotic (DZ) twinning rate in the world (Akhere et al., 2020). In some societies twins are revered and in others they are looked upon with suspicion. At the same time, twin studies are fundamental to the scientific understanding of the role of nature and nurture. Yet surprisingly, up till now, we have had a very incomplete picture of the number of twins around the world. It is only in highly developed countries with good birth registrations that reliable national information on the incidence of twinning and the changes therein over time is available. Information for less developed regions is weak or lacking all together (Smits and Monden, 2011). Multiple births account for 3% of all births worldwide (Pharoah et al., 2010). Globally, recent decades have seen a major increase in multiple births rates (Martin et al., 2012; Pison and D’Addato, 2006). From 1980 to 2009 in the United States, the number of twins has doubled and the twinning rate has risen by more than 75% (Collins, 2007). Similar increasing trends have also been observed in Western Europe and other countries (Pison and D’Addato, 2006). Older maternal age accounts for about one third of the growth in the twinning rate, and the increased use of infertility treatments is likely to explain much of the remainder of the rise (Martin et. al., 2012). Spontaneous multiple birth (i.e., multiple birth not related to Assisted Reproductive Technology) is high in Africa. Studies conducted as early as 1960s witnessed the high incidence of multiple births in Western Africa, especially in Nigeria (Cox, 1963; Nylander, 1971). Pison (2000) established that out of 2.8 million twins born worldwide, nearly 1.1 million (42%) were born in Africa as compared to 39% in Asia, 13% in America and 6% in Europe (Pison, 2000). Another study found very high twinning rates (above 18 out of 1,000 births) in many Central, Western, and South-Eastern Africa countries (Smits & Monden, 2011). Studies conducted in Nigeria (Akinboro et. al., 2010), Ghana (Mosuro et. al., 2001), and Kenya (Musili & Karanja, 2009) concluded the same. According to Christian et. al. (2021), the highest rate of twinning is found in Africa (16.5%), percentages of twinning in other continents include; Oceania (10.1%), North America (9.9%), Europe (9.1%), South America (8.7%), and Asia (7%). Rebecca (2022) also reported that in a study carried out in 2008 by researchers, the highest twinning rate (40.2% twins per 1000 births) was found in Nigeria particularly in southwestern states where Igbo Ora is located. The researchers also established that high twinning rate was prevalent among the Yoruba ethnic group. Wikipedia (2021) rated IgboOra has the town with the highest twinning rate (45 to 50 sets of twins per 1000 live births) behind Velikaya Kopanya, Ukraine (122 twins in a population of 4,000) and Kodini, India (204 sets of twins and 2 sets of triplets born to 2,000 families). Other towns with high twinning rate include; Candidi Godoi, Brazil (One in 10 births involves twins), Mohammadpur Umri, India (One in 10 births involves twins) and Abu Atwa Ismaila (One in 9 births involves twins). Multiple birth is a heritage of Igbo-Ora, a small town in Oyo State, Nigeria. Igbo-Ora is referred to as the twin capital of the world. According to Alexis (2019), out of 100 senior secondary school students assembled, 12 were twins. Another peculiarity of high twinning rate in Igbo-Ora according to Emelike (2021) is that there are twins and triplets in virtually every household and he described the town as the twin capital of the world. This particular pattern of twinning differentiates Igbo-Ora from other towns with high twinning rate. The local authority (Oyo State Government) just started recognizing the high population of twins in Igbo - Ora as a rare and amazing heritage resource to tap for tourism with the first twins’ festival which took place on October 13, 2018 (Onyekwusi, 2019). The Nigerian Bureau of Statistics indicated unemployment rate as 33.3% as at the first quarter of 2022. This shows that one out of every three Nigerians is unemployed or underemployed. According to World Bank (2022) sluggish economic growth, low human capital, labor market weaknesses, and exposure to shocks are holding Nigeria’s poverty reduction back. The World Bank result shows that 4 out of 10 Nigerians live below the national poverty line. Many Nigerians also lack education and access to basic infrastructures, such as electricity, safe drinking water, and improved sanitation. The report further notes that jobs do not translate Nigerians’ hard work into an exit from poverty, as most workers are engaged in small-scale household farm and non-farm enterprises; just 17 percent of Nigerian workers hold the wage jobs best able to lift people out of poverty. The report added that climate and conflict shocks which disproportionately affect Nigeria’s poor are multiplying, and their effects have been compounded by COVID-19; yet government support for households is scant. Households have adopted dangerous coping strategies, including reducing education and scaling back food consumption, which could have negative long-run consequences for their human capital. Deep structural reforms guided by evidence are urgently needed to lift millions of Nigerians out of poverty. In line with the information above and its economic consequences, many Nigerian families who hitherto are lover of having many children and large family size are beginning to cut down on number of children, although there are still large number of uneducated and people who don’t really care and are not prepared to properly train children who still bear many children. The implication of this on multiple birth in Igbo-Ora is that; while some people are cutting down on number of children, some are indifferent. Hence, it cannot be categorically stated whether multiple birth is increasing or decreasing, however, the most important thing is that; regardless of the general status of the family size, multiple birth has continuously and sustainably replicate itself across majority of households in Igbo-Ora. Literature Review Igbo – Ora had been known for a high rate of twinning for a very long time, no wonder the town is usually referred to as ‘the twin capital of the world’. According to Adaobi (2022), while Igbo – Ora remains the twin capital of the world, high rate of twin births has also been observed in Kodinji (India) and Candido Godol (Brasil). More recently and globally, high rate of multiple birth is associated with the evolution of assisted reproductive techniques (Scholten et. al., 2015). Data from the developed countries have shown that while there is a significant drop in the number of triplet or higher order multiple births, the number of twin births has remained stable or continued to rise (Murphy et. al., 2017). However, multiple gestation births remain at higher risk for various morbidities and mortality compared to singletons (Renjithkumar et. al., 2021). Multiple birth is a unique heritage found in Igbo – Ora, Oyo State, Nigeria. This heritage can be developed to promote the tourism potentials of Igbo – Ora. This will contribute significantly in boosting the economy of the community and the country at large (Emelike, 2021). Cultural Heritage is an expression of the ways of living developed by a community and passed on from generation to generation, including customs, practices, places, objects, artistic expressions and values (ICOMOS, 2002). Cultural identity can be tangible such as the built environment, natural environment and artefacts or intangible such as habits, traditions, oral history, etc. One of the main justifications for heritage development, especially from the point of view of government and the private sector, is the value of heritage for tourism and recreation (Hall & Zeppel, 1990; Zeppel & Hall, 1992). The expenditure of visitors on heritage sites and the associated revenue inflow made heritage tourism a big business. For example, heritage is given considerable prominence in United Kingdom, described as “a major strength of the British market for overseas visitors” (Markwell et. al., 1997). In the United States, heritage tourism is also an important sector of domestic tourism, achieving an annual growth rate of 13 percent between 1996 and 2002, with approximately 216.8 million personal trips to heritage sites in 2002, and an average expenditure of $623, a figure almost 50 percent higher than the expenditure of non-heritage visitors (Li et. al., 2008). Heritage travelers are notable for how they spend their money and how they spend their time. Heritage tourists are much more likely to stay in commercial lodging than other vacationers. They are also much more likely to visit a national or state park or visit a museum. They are more interested in eating local foods and going on hikes than other travelers. Although, economics is often the decisive factor in determining whether or not heritage is preserved, it is the social significance of heritage that will typically first arouse interest in preservation (Hall & McArthur, 1993). As noted above, heritage is important in assisting us to define who we are as individuals, a community, culture, and a nation, not only to ourselves but also to outsiders. Therefore, heritage tourism can be both a means of appreciating what we have inherited and a motive to cultivate it. Heritage is also important in determining our sense of place. A sense of place arises where people feel a particular attachment to an area in which local knowledge and human contacts are meaningfully maintained (Hall, 1991). It is the place where we feel most comfortable and where we feel we belong. People demonstrate their sense of place when they apply their moral or aesthetic discernment to sites and locations (Tuan, 1974). Heritage tourism reintroduces people to their cultural roots and helps them form identity (Donert and Light, 1996). Heritage is therefore something which is retained to ensure that certain elements of people’s senses of place remain essentially unchanged. Heritage tourism is widely accepted as an effective way to achieve the educational function of tourism (Ashworth & Turnbridge, 1990; Dean, Morgan & Tan, 2002; Light, 2000). Heritage may have substantial scientific and educational significance. For example, natural heritage such as Volcano and Nyungwe National Parks hold important genetic material and provide a habitat for rare and endangered species. Within these areas various kinds of research on ecological processes may be carried out. Politically, the relationship of heritage to identity meant that the meaning and symbolism of heritage may serve political ends by helping government influence public opinion and gain support for national ideological objectives (Gordon, 1969), promoting national ambitions (Cohen-Hattab, 2004), developing a positive national image (Richter, 1980), and producing national identity (Pretes, 2003). Indeed, the very definition of what constitutes heritage is political. For example, the conservation and interpretation of certain heritage sites over others may serve to reinforce a particular version of history or to promote existing political values. Generally, cultural heritages are important pull factors for tourism, not to talk of distinct and unique attribute of the highest global multiple birth found in Igbo-Ora, Oyo State, Nigeria. Igbo-Ora is a small town with a rich cultural and historical significance in multiple birth. Most households in the town have occurrence of multiple birth. Several studies have linked this to hereditary and consumption patterns which stimulates ovaries of women in the region. Among the Yoruba tribe of Nigeria, twins are so common that they are given specific traditional names. They are called Taiwo and Kehinde depending on whether they were born first or second. But even for Yoruba people, Igbo-Ora is considered to be exceptional in the number of multiple births in the town. According to Alexis (2019), indigenes of the town believed that Okra leave soup and Amala (a local dish made from yam and cassava flour) are responsible for the multiple birth.

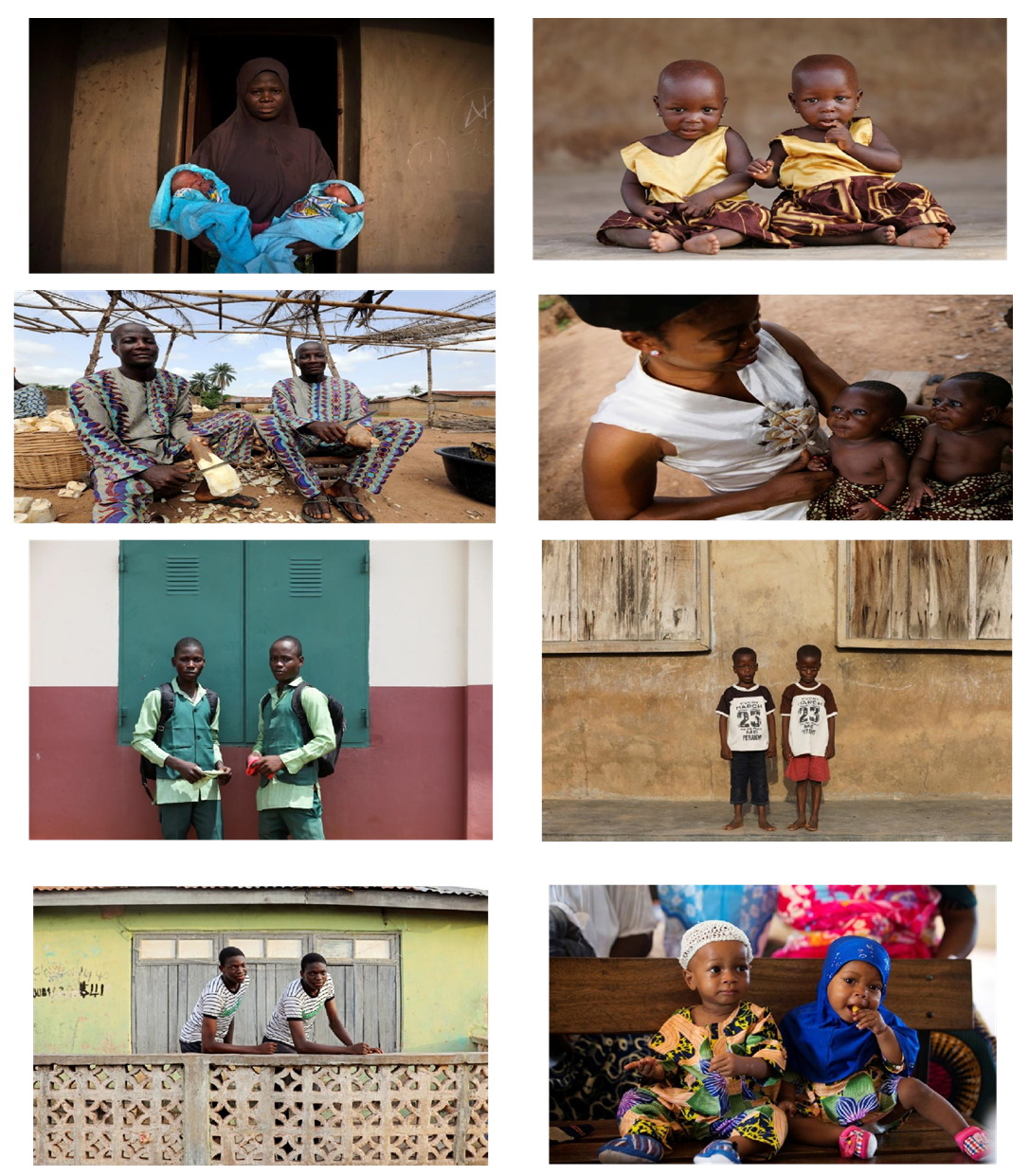

| Plates 1 – 8. The above plates show some of the twins captured by (Alexix, 2019) during his study in 2019 in Igbo-Ora |

2. Methodology

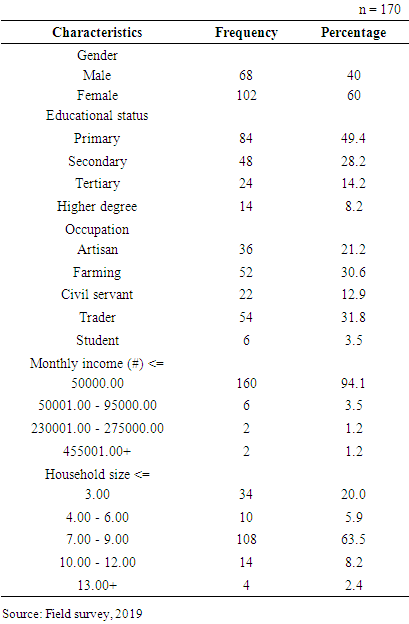

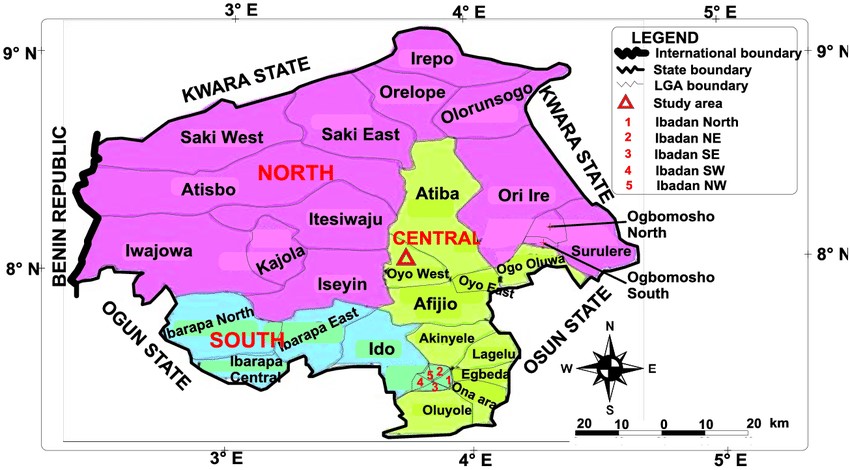

- Study Area: Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa with an estimated population of over 200 million. The country has a population policy that recommends four children per woman but it is hardly enforced. With an annual population growth rate of 3%, Nigeria is projected to be the third most populous country in the world by 2050. The country has over 350 ethnic groups and distinct cultures that accord high value to child bearing and large family size. Multiple births are desired and viewed as a blessing by many ethnic groups in the country (Akhere et. al. 2020). Administratively, Nigeria consists of 36 states and a capital territory, Abuja. Each state is made up of Local Government Areas. This study was conducted in Igbo-Ora, the headquarters of Ibarapa Central Local Government Area of Oyo State, South-west Nigeria, located about 80kms North West of Lagos. Its geographical coordinates are 7° 26' 0" North and 3° 17' 0" East. Igbo-Ora is a rural community and most of the indigenes are peasant farmers and artisans.

| Figure 1. Map of Oyo State, Nigeria indicating the location of the study area |

3. Results and Findings

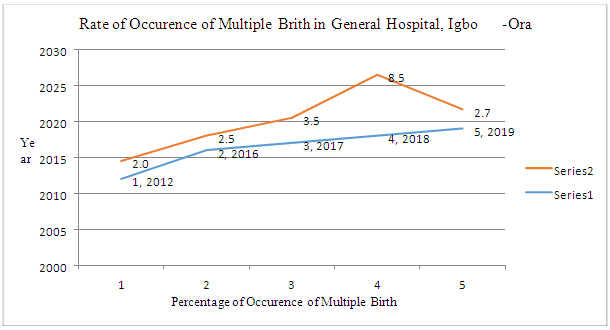

| Figure 2. Rate of Occurrence of Multiple Birth in Igbo-Ora Source: General hospital, Igbo-Ora |

|

= 2.75), high consumption of cassava flour and yam flour with okra leaves soup (

= 2.75), high consumption of cassava flour and yam flour with okra leaves soup ( = 2.60) and intra marriage within the community (

= 2.60) and intra marriage within the community ( = 2.45). Key Informant Interviewer conducted reinforced the causes listed above. Residents stated that; the trait for multiple birth is in their gene, and that intra marriage assisted in multiplying it within their community. Most importantly, they also believe that high consumption of yam and cassava flour and soup made from okra leave grown on their soil also contribute significantly. The causes of multiple births as listed above in the table are not scientifically proved and established but are associated with the native belief of the residents.

= 2.45). Key Informant Interviewer conducted reinforced the causes listed above. Residents stated that; the trait for multiple birth is in their gene, and that intra marriage assisted in multiplying it within their community. Most importantly, they also believe that high consumption of yam and cassava flour and soup made from okra leave grown on their soil also contribute significantly. The causes of multiple births as listed above in the table are not scientifically proved and established but are associated with the native belief of the residents.  | Figure 3. Residents’ Preference between Single Birth and Multiple Birth |

|

|

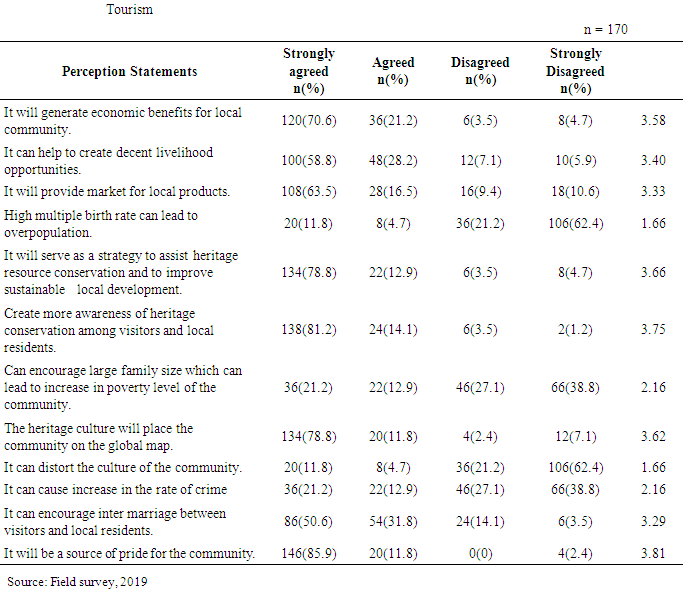

) score of 2.49 and below indicates ‘disagreement’ and a mean score of 2.51 and above indicates ‘agreement’. The table reveals that majority agreed that heritage tourism will; generate economic benefits for local community (

) score of 2.49 and below indicates ‘disagreement’ and a mean score of 2.51 and above indicates ‘agreement’. The table reveals that majority agreed that heritage tourism will; generate economic benefits for local community ( = 3.58), create decent livelihood opportunities (

= 3.58), create decent livelihood opportunities ( = 3.40), provide market for local products (

= 3.40), provide market for local products ( = 3.33), serve as a strategy to assist heritage resource conservation to improve sustainable local development (

= 3.33), serve as a strategy to assist heritage resource conservation to improve sustainable local development ( = 3.66), create more awareness of heritage conservation among visitors and local residents (

= 3.66), create more awareness of heritage conservation among visitors and local residents ( = 3.75), place the community on the global map (

= 3.75), place the community on the global map ( = 3.62), encourage inter marriage between visitors and local residents (

= 3.62), encourage inter marriage between visitors and local residents ( = 3.29), and serves as a source of pride for the community (

= 3.29), and serves as a source of pride for the community ( = 3.81). However, majority disagreed that; multiple birth rate can lead to overpopulation (

= 3.81). However, majority disagreed that; multiple birth rate can lead to overpopulation ( =1.66) and encourage large family size which can lead to increase in poverty level of the community (

=1.66) and encourage large family size which can lead to increase in poverty level of the community ( =2.16). Also, majority disagreed that heritage tourism can distort the culture of the community (

=2.16). Also, majority disagreed that heritage tourism can distort the culture of the community ( =1.66) and lead to increase in crime rate (

=1.66) and lead to increase in crime rate ( =2.16). The result shows that the respondents have a very good perception of heritage tourism and cannot wait for it to be harnessed for sustainable development.

=2.16). The result shows that the respondents have a very good perception of heritage tourism and cannot wait for it to be harnessed for sustainable development.

|

4. Discussion

- According to UNESCO (2021), heritage encompasses tangible and intangible, natural and cultural, movable and immovable and documentary assets inherited from the past and transmitted to future generations by virtue of their irreplaceable value. The term ‘heritage’ has evolved considerably over time. Initially referring exclusively to the monumental remains of cultures, the concept of heritage has gradually been expanded to embrace living culture and contemporary expressions. As a source of identity, heritage is a valuable factor for empowering local communities and enabling vulnerable groups to participate fully in social and cultural life. According to Heritage perth (2021), heritage is about the things of the past which are valued enough today to save for tomorrow. Heritage can have a very positive influence on many aspects of the way a community develops. Regeneration, housing, education, economic growth and community engagements are examples of the ways in which heritage can make a very positive contribution to community life. This is because the historic environment or feature is a source of benefit to local economies particularly through tourism. The attractive heritage feature assists in attracting external investment as well as maintaining existing businesses of all types and not just tourism related. Heritage places can be a potent driver for community action. Increased community values and greater social inclusion can be achieved through a focus on heritage matters. This study established that the indigenes of Igbo–Ora strongly believed that high level of consumption of cassava/yam flour with okra leave soup is one of the important factors responsible for the high rate of multiple birth in their community. Though this belief is not scientifically proven, however, it is usually the case in many African communities having heritage assets, where certain belief is attached to the heritage. For instance, in the Gambia according to Abigail et. al. (2005), by performing certain rituals at the Kachikally Sacred Crocodile Pool, solutions are offered for anyone with long standing ailment and woman having infertility problem. This is also in line with the submission of Kyle et. al. (2016) who stated that women with fertility problem usually visit Osun Osogbo Sacred Grove in Nigeria for solution. This study showed that the locals appreciate their heritage. This is indicated by majority’s (72%) preference for multiple birth over singleton birth. This corroborates the finding of Gyan and Dallen (2010) who discovered that the locals appreciate the heritage properties in their domain by showing positive attitude towards them. Tourism, being one of the most intriguing sustainable development themes has become a popular economic development tool in many countries today. Tourism-related activities are widely regarded as key-tools for rural development, especially in developing countries. Villages are today some of the places attracting the attention of tourism planners more than ever before. Those villages with specific natural or socio-cultural appeal have strong potentials for attracting tourists from close or far off areas and this can have significant role in rural development if well planned and integrated (Iwuagwu et. al., 2017). This study showed that the respondents have a very good perception of heritage tourism and cannot wait for it to be harnessed for sustainable development. This study also showed a positive and significant relationship between education and residents’ perception of developing multiple birth for heritage tourism. This implies that; the higher the level of education, the better the perception of developing multiple birth for heritage tourism.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The high rate of twinning found in Igbo-Ora no doubt has put the small town on the global map. This is a very unique attribute that can continuously and sustainably pull tourists to the community. Hence, infrastructural development, employment opportunities, and general community development is very close to the community if this begging heritage asset is sustainably developed. This study established that the residents have a very good perception of heritage tourism than can be explored via this touristic asset. It is therefore recommended that; stakeholders such as; Igbo-Ora Descendant and Development Associations, Igbo-Ora Traditional Council, Oyo State Tourism Board, Nigeria Tourism Development Corporation (NTDC), Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and private individuals should work together towards branding and positioning multiple birth for sustainable heritage tourism. Also, the so much rated yam flour and Okra leave meal believed by the residents to be responsible for the multiple birth should be developed for culinary tourism as a component of the main heritage tourism. Modern strategies of branding cultural heritage events such as; celebrity shows, raffle draw, beauty pageant contest, cooking and eating competition (which will showcase local foods associated with twin in Yoruba land in Nigeria such as; beans, sugar cane, adun, ekuru etc.) among others should be incorporated while harnessing the touristic asset.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML