-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Tourism Management

p-ISSN: 2326-0637 e-ISSN: 2326-0645

2021; 10(2): 17-24

doi:10.5923/j.tourism.20211002.01

Received: Sep. 12, 2021; Accepted: Oct. 13, 2021; Published: Oct. 30, 2021

Stakeholders Involvement in the Development of Cultural Landscapes for Tourism Development: A Case of Osun Grove, Osogbo

Adhuze Olasunmbo1, Fadamiro Joseph2, Ayeni Dorcas2

1Department of Architectural Technology, The Federal Polytechnic, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State

2Department of Architecture, The Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State

Correspondence to: Adhuze Olasunmbo, Department of Architectural Technology, The Federal Polytechnic, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

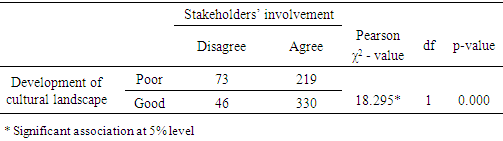

The cultural landscape is an expression of human interaction with the environment over centuries but has now been recognized and promoted as a tourism destination for tourists who wish to know about the history and other experiences of tourism on such sites because of its rarity in these times. The culture of a people is embedded in this site but are they involved in determining what kind of development comes to the site? This description is such of the Osun grove, Osogbo, one of the two UNESCO World Heritage sites in Nigeria. This study examined the challenges of tourism development at the site and the involvement of major stakeholders in its sustainability. It was carried out using a mixed method of a structured questionnaire (n=384) and an unstructured interview (n=8). Results of the quantitative data revealed that there is a significant association between developing the cultural landscape and local stakeholders' contribution, the result of the content analysis of the interview data revealed that stakeholders are not as involved in the decision-making process as they should. The study concludes with suggestions on an improved mode of participation of stakeholders in the overall development of the site for the present and future sustainability plans.

Keywords: Cultural Landscape, Heritage, Tourism, Osun grove, Sustainability

Cite this paper: Adhuze Olasunmbo, Fadamiro Joseph, Ayeni Dorcas, Stakeholders Involvement in the Development of Cultural Landscapes for Tourism Development: A Case of Osun Grove, Osogbo, American Journal of Tourism Management, Vol. 10 No. 2, 2021, pp. 17-24. doi: 10.5923/j.tourism.20211002.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In the case of a cultural landscape, which is a historic site, tourism is a way of exhibiting the cultural heritage of the people to the outside world but with a hope of preserving the heritage of the people. But tourism as a tool for change, economically, environmentally, and socially, also affects the daily lives of the local community, by a breeding change which are in most cases unexpected and with far-reaching consequences. Effective stakeholders’ engagement is considered to be critical as it can reduce potential conflicts between the tourists and host community by shaping how tourism develops' (Aas, Ladkin, and Fletcher, 2005). Eshliki and Kaboudi (2017) posit that the local population's attitudes toward tourism are important since it is the community that creates an enabling and comfortable environment for the tourist’s memorable stay. This amplifies the importance of the stakeholders for operative tourism development and sustainability. Getz and Timur (2005) suggest that local communities are primarily apprehensive about how tourism will impact their locality, way of life, and the essential need for sustainability. They are therefore supportive or otherwise in the development of tourism on their soil depending on how it is presented to them and how they perceive its effects.While most studies have been steered from a developed country tourism perspective, few have been carried out from a developing world standpoint. The main purpose of this paper, therefore, is to analyze the effects of tourism on the local community, and the degree of community participation in Tourism Planning and development in the Osun Osogbo Cultural Grove, one of two UNESCO World Heritage sites in Nigeria. More specifically, the paper is set to analyze the importance of community participation in tourism development programs and to evaluate the future effects of a purposeful involvement of the local community in participatory tourism development at the Osun grove, Osogbo.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Stakeholders’ in Tourism Development

- The tourism industry is large and accommodating to all who can contribute to its growth and development as it has been identified as one of the industries that make the fastest contribution to economic growth. The tourism industry is supposed to provide pleasure and satisfaction, create wealth and add value to those who wish to experience it as anyone or participants with tourism are then regarded as stakeholders. Clarkson (1995), described stakeholders as all entities which become either willingly or unwillingly exposed to any activity of an organization that can pose a risk to them in one way or the other. Clarkson, talks about the exposure to risks, opining that the only thing that qualifies one to be a stakeholder is the risk that one is willingly and unwillingly open to. Post, Preston, and Sachs (2002) looked at it from another perspective and defined stakeholders as individuals or groups which add value to the wealth creation of an organization and are also its potential beneficiaries and beneficiaries, in this case, can be of both the liabilities and the assets of the industry. This in all rights should put them in a vantage position as decision-makers since they will be affected by whatever happens. Nicolaides (2015) posits that these stakeholders are those individuals and groups that have a claim or an interest in the tourism plan and activities of a place and also possess the ability to influence those activities in some way. The interest could be in the benefits they get from the industry and are also influencers because of the contributions they make in the industry. This category of people will also bear the pains or trials that come along with the benefits and opportunities of the site. Tourism stakeholders are, therefore, those who are willing to take up not only the benefits and advantages of tourism but also the associated risks and liabilities for sustainable development. According to the UNWTO, the stakeholders include inter alia, tourism professionals such as travel agents, tour operators, hotels, taxis, public authorities, the press, and all the media. Swarbrooke (2001) divided stakeholders into five major categories namely: government, tourists (both domestic and foreign), the host communities, tourism businesses, and other related sectors. All these groups are major players in the tourism industry, the government at the highest level has economic benefits from tourism, from the currency exchange to the taxes paid by all firms that have to do with tourists. The local communities, which play host to the tourist site and tourists themselves, have all cultural, social, and economic benefits to derive. The levels of involvement of these categories of stakeholders are not the same, so are their benefits. In most cases, the level of involvement also does not commensurate with the benefits that accrue to the stakeholders because in most cases, the most relevant ones to the development of tourism are the government and the local community. The government has the powers to make things happen, she has the money and formulates the policies, and takes the decisions as regards the landscape. She also has the power of enforcement at hand putting in place all the agencies at her disposal. In addition, the local communities have the greatest assets that tourists come to seek out. The local population’s attitudes toward tourism are important given the argument that a happy community is more likely to support tourism development and welcome tourists (Snaith and Haley, 1999). Although the local communities are not usually involved in decision-making as regards the development of tourism around them, they come in regular contact with the tourists and are most affected by cultural influences. These communities are likely to suffer from traffic congestion, increasing crime rates, wastewater generation, and increasing cost of living (Nunkoo and Ramkissoon, 2009). The acceptance and emphasis on local participation and community approach to tourism development imply that host members are often excluded from not only planning but decision-making and management of projects (Nicolaides, 2015). Teye et al (2002) also affirmed that the exclusion of the communities is a common practice in developing countries with top-down development cultures. This unfortunately has not supported the growth of tourism in the developing country, rather the top-down approach dampens the growth of the sector as far as the local communities are involved. In developing countries, local community participation in the decision-making process of tourism development has often been lacking, limited or sometimes marginalized (Dola and Mijan, 2006). However, where sustainability is to be practicable, there is the need for an inclusive and harmonious working together of all stakeholders especially the local communities.

2.2. Stakeholders and Sustainable Tourism Development

- It is often observed that local communities are disregarded and overlooked when it comes to the management of the site. This was emphasized in the draft report of the Department of Environment for the management of sustainable tourism in Ecologically Critical Areas in Cox’s Bazar (2008) that the current tourism pattern marginalizes locals; as poor communities in the area receive no significant benefits from tourism rather than paying some of the social and environmental costs of this activity. It also states that involving locals in management can be done either by delegating tourism rights to the community level or by ensuring that government planning processes are participatory and responsive to local needs (GhulamRabbany, Afrin, Rahman, Islam and Hoque, 2013). The sustainable tourism industry is predicated upon several factors; in particular, is the consideration that should be given to the impact that tourism has on the host community (Cahndralal, 2010). To attain sustainability in the tourism sector, necessary considerations of all industry players are important factors. Benson (2014) posited that sustainable tourism development requires the informed participation of all relevant stakeholders, as well as strong political leadership to ensure wide participation and consensus-building. Achieving sustainable tourism is an unceasing procedure and it entails constant monitoring of impacts, introducing the necessary preventive and/or corrective measures whenever necessary and timely. Shah et al (2002) discuss the promotion of sustainable tourism, among other things, asserted that local involvement is among the essential goals for achieving sustainability. UNESCO's World Conference on Sustainable Tourism, Spain (1995) developed a specific framework for sustainable tourism to grow from, one of the major highlights of the conference is the participation of all actors in tourism development and this can begin with the inclusion of the local communities in the decision-making process to promote and attain sustainability.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area

- The study will be carried out in the dense forest of the Osun Sacred Grove whose landscape and its meandering river is dotted with sanctuaries and shrines, sculptures, and artworks in honor of Osun (the river goddess) and other deities are located in the heart of Osogbo, the capital city of Osun State as shown in plate 1. It stands as one of the last remnants of primary high forest in southern Nigeria with protected relics of an older generation that habour the goddess of water that is worshipped in a flamboyant ceremony, once every year to bless and heal the infirmities of the land (Oni, 2016). The grove sits on a 75 hectare of land and is regarded as the abode of the goddess of fertility Osun, one of the pantheons of Yoruba gods (UNESCO, 2013). The sacred grove, which is now seen as a symbol of identity for all Yoruba people, is probably the last in Yoruba culture. Within the forest sanctuary are forty shrines, sculptures, and artworks erected in honour of Osun and other Yoruba deities, many created in the past forty years, two palaces, five sacred places, and nine worship points strung along the river banks with designated priests and priestesses. There is an annual festival held in honour of the Osun deity in the grove which draws both the adherents of Osun and a heavy presence of local and foreign tourists. It is one of the most recognized African festivals that attracts over one million tourists across the globe and one of the major cultural assets that attract world attention in Nigeria (Olukole, 2014). With all these exposures already accrued to the grove, it stands as an appropriate location to look at the challenges of flood on tourism.

| Plate 1. Google site of Osun grove, Osogbo. Source: Google maps, 2017 |

| Plate 2. Gate leading to the core of the grove. Source: Author’s fieldwork, 2019 |

3.2. Research Instrument

- The study adopted the mixed-method approach to analyze through the feedback of the participants who are residents of the state and who form the local community to the site, their level of participation in the decision-making process of the development of tourism on the heritage site. The data for the study were collected by the use of a structured questionnaire administered on 384 residents of Osogbo, a cluster sampling strategy was used to gain a representative sample of the population. The metropolitan area of Osogbo (comprised of Osogbo and Olorunda Local Government Areas) was divided into 26 political clusters or wards (i.e., 15 in Osogbo and 11 in Olorunda) according to classification by the Independent Electoral Commission of Nigeria (INEC). Wards were selected randomly and at that point, every fourth house was selected within each ward. The questionnaires were administered between Mondays and Saturdays for four weeks between May and June 2019 and were retrieved on the days they were administered. The interview was conducted also within the same period and was captured with the aid of a recorder and jotting of salient points by the interviewer with the consent of the interviewee before the interview began. Each interview took less than 20 minutes in the offices of the interviewees or a convenient open place, as the objective was explained beforehand to them and the willing ones who consented were interviewed. Since this work is principally related to stakeholders in the tourism sector, the participants were essentially people who had been identified to be part of the stakeholders from research and existing documents as related to the grove. According to Oyeleke, Ogunjemite, and Ndasule (2017), stakeholders at the grove were categorized into four, which are traditional, institutional, Non-Governmental Organisations, and others. The interview cuts across these categories of people based on convenience and willingness to grant the interview. In all, 8 people were granted the interview and their responses have been captured and recorded, and analyzed in this work. The responses to the questionnaires were analyzed quantitatively while the interview was analyzed with the responses to the questions they were asked. Chi-square was then used to test the association between the development of tourism on the cultural landscape and the local stakeholders’ contribution.Among the different approaches explained by Creswell (2007), the authors adopted the grounded theory approach, as it is the most suitable for the phenomenon studied. Grounded theory is an approach in which researchers generate general explanations of processes, actions, or interactions extracted from the perspectives of some experienced participants (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). This procedure could be applicable, for example, in the process of developing a sustainable tourism model for the grove. (Creswell, 2007). According to the Conservation Management Plan of the Osun grove as prepared by the National Commissions for Museums and Monuments, categorized main stakeholders into four; traditional stakeholders, institutional stakeholders, non-governmental stakeholders, and educational institutions. This has left out service providers and tour operators whose impacts on the development of the tourism sector cannot be exaggerated, creating a gap already, but this study captured all these sets of stakeholders.

4. Results and Discussion on the Structured Questionnaire

4.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

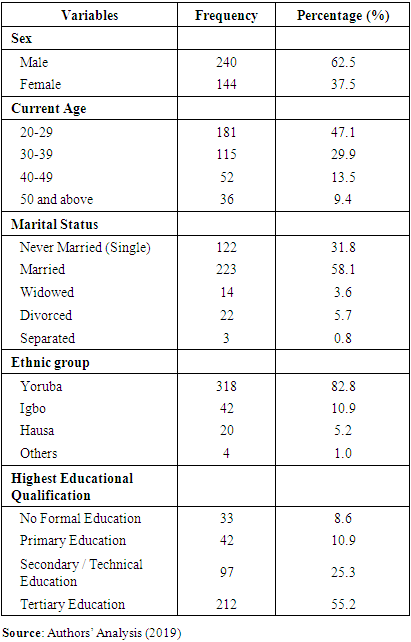

- Over half of the participants (77%) were aged 20-39 years old while only 9.4% of the participants were 50 years or older. Participants were mostly male representing 65.5%. In addition, 58.1% were married at the time of the study, whereas 31.8% were not yet married and 6.5% were previously married but now separated or divorced. More than half of the participants (55.2%) had tertiary education while only a few (8.6%) have no formal education. (Table 1)

|

|

4.2. Findings and Discussions on Interview

- This section presents analyses and discusses the findings of the survey. The responses were all grouped into two themes; the first theme denotes assuring the proper inclusion of stakeholders through a willingness to partake in responsibility and activity regulation. The second theme refers to reinventing the wheel of tourism development through the stakeholders and this by professional inclusion and effective communication system.

4.2.1. Theme 1: Assuring the Proper Inclusion of Stakeholders

- More than half of the responses (n=5, 62.5%) focused on assuring that there is an inclusion of all stakeholders in tourism development and not limited to the annual festival that takes place on the site. The opinions of the participants were analyzed and two categories that emerged included a willingness to partake in the responsibility of developing the site and regulating the activities of the stakeholders involved in the development of the site.

4.2.2. Willingness to Partake in the Responsibilities of the Development of the Site

- Willingness to partake in the responsibilities of the development of the site was the concern of four participants. These responses confirmed the significance of including stakeholders, who have genuine love and concern for the improvement of the grove. This is in line with the findings of researchers, who affirmed that there exists an issue of interest and convenience, which influenced the involvement of the stakeholders in cultural heritage preservation as some stakeholders were inconvenienced to communally be involved in the effort, while some got involved with ease as it is embedded in their everyday routine (Bakar, Osman, Bachok and, Ibrahim, 2014). “Creation of a stakeholder’s forum dedicated to the development of tourism on the site”. (P01)“Composition of the stakeholders needs to be revised”. (P07)“Only those intentional about developing the site and not only making money out of it should be invited into the forum of stakeholders. (05)The respondents called for revising the selection of stakeholders that will be invited to join in the forum to become more effective, efficient and ensure that value is added to the tourism plan of the site by their presence and contributions. This is not limited to the ideas and information these people bring to the forum but more important is the financial commitment which they can fulfill. In the discussion, they asserted that the current composition exists basically for the annual festival which takes place on the site, positing that there should be a concerted effort at developing the site for tourism beyond the festival. They emphasized that valuable and unwavering effort by people who are intentional about the development of the grove in the stakeholder’s forum will yield needed results and this should not exclude the local communities. It was also gathered, that in most cases where there is a new development scheduled to take place on the site; it often comes as instruction and not a deliberation between the stakeholders to examine its consequence on the community. This shows a top-bottom approach on the management of the site, which might not be beneficial for appropriate development required for the grove, which is in line with the findings of Oyeleke, Ogunjemite, and Ndasule (2017).

4.2.3. Activity Regulation

- Another issue that appeared in the regulation of the activities of each stakeholder to avoid conflict of interest and usurping of another's the responsibility, all in the name of efficiency. Four participants offered some considerations related to regulating each stakeholder's activity as there is no clear definition of activities. This issue was raised especially in the area of revenue collection from traders and temporary service providers during the festival, locals complained that more than one unit of stakeholders demand payment for selling items or displaying goods for sale and this puts a lot of burden on the locals who are trying to make a living for themselves using the opportunity of the crowd at the festival. However, since more than one institution is demanding payment, it makes it less attractive and burdensome on the locals, reducing the profit they make from the quick business and decreasing their zeal for the business venture. The statements below reflect the participants’ states of mind.“We should not be made to pay more than once for the ticket on any day we sell. The payment should be better organized." (P03)“… Payments made for support should not be such that belabors those that are levied, because we will also look for a way to make back such monies or else we will run at a loss.” (P05)The administration of the grove by reducing the levies paid by the common man and other investors who are service providers was the concern of another two participants. The administration must provide the enabling environment for small-scale businesses to thrive without over-stressing them with bills and levies, which they may find difficult to meet up with, rather, they should find a common ground where all will joyfully contribute financially and still reap the benefits of the site.

4.3. Theme 2: Reinventing the Wheel of Tourism Development through the Stakeholders

- Half of the responses (n=7, 87.5%) focused on reinventing the wheel of tourism development through the stakeholders. They opined that professionals’ inclusion is a necessity if sustainable tourism is the target for the tourism in the grove and that a conscious and deliberate tourism development plan has to be set up for the development of the site, which should not leave out the local community.

4.3.1. Professionals Involvement

- Five participants supported a view that professionals in tourism development should be involved at all levels of the administration of the grove. They emphasized the necessity of aligning sustainable tourism development with the marketing of the site so that both the tangible and the intangible qualities of the site can be preserved without leaving out the local communities. This would be through a cohesive, interdisciplinary operation between the community members, conservation agencies, marketers, and tourism agencies. “The professionals should be included in the decision–making process, so that a proper development model can be developed to secure the site, not just for money-making.” (P04)“If the professionals are involved, we are likely to preserve the essence of the site more than when they are not.” (P01)Participants advocated that the inclusion of tourism agencies into the stakeholder’s forum, adequate funding, and provision of necessary professional recommendations are crucial to the development of tourism in the grove.

4.3.2. Effective Communication System

- Five participants believed that an effective communication system is a key to sustainable tourism in the Osun grove, Osogbo. They call for a line of communication that will give every stakeholder a sense of belonging. They also opined that a medium of communication where the common person can give advice or complain about activities observed in the site without bottlenecks should be created. This will encourage the locals to give real-time information on activities observed in and around the site for security and to prevent any form of degradation. Four responses extracted to reflect this meaning include;“I need to be able to report any bad or illegal observation in or around the grove real-time, but where I do not have that means we cannot protect the site or the tourists which is our responsibility.” (P06)“If I am regarded as a stakeholder, then I need to be carried along in the activities of development happening on the grove.” (P07)“Community involvement interventions, information dissemination spots, and community participation models are all ideas which can be harnessed to develop a channel for feedbacks.” (P03)“We the commoners are the ones that most relate with the tourist, we get feedback on ideas to improve the site but there's no way these ideas can easily get to the administration.” (P04)The above quotes show that the experience of the local community people in tourism development as feedback from the tourists could be a first-hand idea that is only waiting to get to the authorities but may never get to them. It is therefore vital, to set up feedback points and avenues where the locals can reach the development authorities on issues bothering the grove. This has confirmed the position of Bakar, Osman, Bachok and, Ibrahim (2014) & Eshliki and Kaboudi (2017) that community access to information is crucial to the development and safeguarding of a cultural heritage site.

5. Conclusions

- This study, as a part of a research project, targeted an in-depth exploration of stakeholders' perspectives on the development of cultural landscapes for tourism. It reviewed the contemporary and current issues on stakeholders’ participation in tourism development. It adopted a mixed research method through the interview carried out among a sample of eight local stakeholders in Osogbo, Osun State, the site of the cultural landscape. It also used the content analysis technique to conclude the answers of participants. In comparison to earlier studies, the findings of this study indicated a broader range of perspectives.Some results were in line with related ones from earlier studies but community access to information, consultation and decision-making, community ideas, and opinions are significant factors that were exploited. Community members should be brought into the decision-making process since they have a direct experience with tourists and activities in the grove. Development of the grove for tourism should be intentional and commitment should be the first condition of involvement. Finally, the deliberate inclusion of professionals in the development to improve practical-based activities geared at the sustainability of the cultural landscape are challenges that need to be overcome. This study is not without its limitation, as interviews were not in some cases granted by high officials who could give information on the constitution and conditions of participating in the stakeholder's forum. In some other cases, some locals did not even take the interview seriously as it was discovered that they told obvious lies about the information required which does not validate existing situations. However, this study has revealed that the success of sustainable tourism development on a cultural landscape is largely dependent on the involvement of all the stakeholders to the site who bring their wealth of experience to the table of deliberation and decision-making but only when they are invited. From the local to the international stakeholders, there is the need for a platform where contributions can be made to foster the development of sustainable tourism in the cultural landscape to protect both the tangible and intangible heritage of the site. Only when this is done can the cultural landscape be properly preserved and heritage protected.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML