-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Tourism Management

p-ISSN: 2326-0637 e-ISSN: 2326-0645

2021; 10(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.tourism.20211001.01

Received: Jan. 28, 2021; Accepted: Mar. 10, 2021; Published: Mar. 28, 2021

Impact of Exchange Rate on Trade: A Case Analysis of Congolese Partners

Mourou Roscelin Serge Carrel1, Ngolali Ngoulou Rigobert Wilfried2

1School of Economics, Shanghai University, 716 Jinqiu Road, Baoshan District, Shanghai, China

2Department of Public Law, Paris Descartes University, France

Correspondence to: Mourou Roscelin Serge Carrel, School of Economics, Shanghai University, 716 Jinqiu Road, Baoshan District, Shanghai, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Exchange rate fluctuation has an important impact on export trade. It can affect the total volume of trade by affecting the price of trade commodity and the change of national income.The data used evaluates a series of exchange rates from January 2000 to December 2019, where export & import volumes are considered from the point of their determinants, including exchange rate volatility, measured through GARCH model. The results for this Congolese case show that short run dynamics negatively discouraged with both export & import. This implies that Congolese should opt for direct domestic currency when trading with partners.

Keywords: Exchange Rate Fluctuation, Trade, Foreign Exchange Policy, International Financial Market

Cite this paper: Mourou Roscelin Serge Carrel, Ngolali Ngoulou Rigobert Wilfried, Impact of Exchange Rate on Trade: A Case Analysis of Congolese Partners, American Journal of Tourism Management, Vol. 10 No. 1, 2021, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.tourism.20211001.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Since the reform and opening up, The Republic of Congo has entered the global economy and financial market system, and has formed a trade based development model focuses on export.Exchange rates affect the true prices of commodities traded among countries of the world; it determines the price actually paid when each trade transaction is executed. At the same time, domestic inflation also plays a vital role in determining the changing patterns in the prices of tradable commodities.High-frequency data contains values recorded on the basis of monthly, weekly, daily, or even minute-by-minute intervals. Recent studies on exchange rates have also started to employ high-frequency data (see Andersen, Bollerslev, Diebold, & Labys, 2001; Canales-Kriljenko & Haber Meier, 2004; Qayyum & Kemal, 2006; Beine et al., 2006). We consider monthly data relevant to our study on the assumption that the derived demand for currency exchange emerges through the demand for exports or imports where order placement, production, and delivery entail a gestation period of probably more than a week.Shah et al, (2010) Argued that fluctuations of exchange rate either depreciation or appreciation have a different effect on trade, it effects on the price level of the supplies to be exported and also the goods to be imported. The overall balance of export proceeds and that of import payments verify the trade balance of a country and payment it determines the position of the current account. Fluctuations of exchange rate create the uncertainty in the shape of reducing the trade volume. According (Sandu & Ghiba, 2011) exchange rate instability discourages the international trade. They examined the relation between exchange rate and exports of Congo and further. In which he found there is an inverse relation between exchange rate and exports in Congo.The Congolese trade is dominated by the oil sector, which, in 2004, accounted for over 50 percent of GDP, more than 70 percent of government revenues, and almost 85 percent of merchandise exports. Oil production is mainly located offshore and managed by joint ventures between international companies and the national oil company (Société Nationale des Pétroles du Congo, SNPC). Ancillary oil-related services are dominated by international groups, and the bulk of their supplies are imported. The volatility of the nominal exchange rate increased with the rising exchange rate (depreciation), but remained low or declined when the exchange rate appreciated. This could imply that depreciation caused higher instability and appreciation stabilized the exchange rates (Azid et al., 2005). The Congolese exchange rate regime has shifted from being fixed to FCA, and to a floating regime. It is an important macro variable that influences the whole economy therefore attracts keen attention of researchers (Backman, 2006). The exchange rate determines the price of domestic as well as foreign goods so it affects the worth and volume of exports sold and in return import bought, and its impact on trade balance (Elwell, 2012). The devaluation of exchange rate protects essentially to guide and enhance the balance of payment (Ahmed, Ahmed, Khoso, Palvishah, & Raza, 2014).According to (Dognalar, 2002) the effect of exchange rate fluctuations on export of five developing countries along with Congo in which he concluded that broad relationship exists between the exchange rate and export, further as concluded that exporters are the risk avoided because the exchange rate instability would be reason to exporter to reduce the export in that conditions. (Ragoobur & Emamdy, 2011) Concluded that positive impact examined for a short run while fluctuations in exchange rate expected in long run.Moccero and Winograd (2006, p.2) indicate that the theoretical literature on the impact of exchange rate fluctuations on trade and the resulting demand for stable anchors (exchange rate fixing) have long been a highly debated topic among economists. Traditional models examined the exchange rate volatility effect on trade based on the producer theory of the firm under uncertainty, where firm profitability is related to exchange rate fluctuations. Some theoretical models point to a positive relationship. Baron (1976) shows how an increase in exchange rate volatility may not necessarily lead to an adverse effect on the level of trade when hedging opportunities exist.The last two decades suggests that there is no clear-cut relationship one can pin down between exchange rate volatility and trade flows. Analytical results are based on specific assumptions and only hold in certain cases. Especially, the impact of exchange rate volatility on export and import activity investigated separately leads also to dissimilar conclusions among countries studied (Baum and Caglayan, 2006). So, how exports associated with exchange rate volatility, and what about the relationship for imports? This paper presents an empirical investigation of Congolese trade impact of exchange rate fluctuations in from the perspective of export and import. In the presence of conflicting and ambiguous findings of prior studies, scrutinizing the relationship between exchange rate volatility and export/import volumes is purposed in this research. The contribution of this paper is that the study of dubious relationship between exchange rate fluctuations and trade from the perspective of both export and import simultaneously has not been performed for the case analysis of Congolese trading Partners.

2. Objectives of the Study

- The objective of this paper is to examine the impact of exchange rate trade on a case analysis of Congolese trading Partners.

3. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

- Studies in the literature have investigated the impact of volatility on exports: Franke (1991) and Sercu and Vanhulle (1992) find that an increase in exchange rate volatility increases the value of exporting firms and thus promotes export activities. Broll and Eckwert (1999) observe that exchange rate volatility increases the option to export to the world market because of the higher potential gains from international trade for risk seekers. Other studies show that higher volatility leads to more gains from international trade (see Brada & Méndez, 1988; Sercu & Vanhulle, 1992; De Grauwe, 1994). Côté (1994) argues that exchange rate volatility has direct and indirect negative effects on international trade through uncertainty, adjustment costs, the allocation of resources, and government policies. A report by the Commission of the European Communities (1990) states that “the reduction of exchange rate uncertainty is necessary to promote intra- EU trade and investment.” Dell’Ariccia (1999) finds that increased exchange rate volatility has had a small but significant impact on trading among 15 European Union members where the reduction in volatility to zero allowed them to expand their trade by 3–4 percent.Bashir et al., (2013) Concluded that the exchange rate fluctuations of Congolese destabilizes the exports with main trade partners and consequently affected the economy and growth of the country. So for the purpose of economic development, it’s needed either control or forecasts the exchange rates in order to minimize uncertainty having effects on exports of Congo and adopted a valid strategy to control the ambiguity and uncertainty of exchange rates. In Congo monitory policy must be controlled to avoid the instability in the exchange rate to protect the exporters from the risk of loss of their equity.Exchange rate instability affected by financial market growth. In such conditions instability having tough insinuation on foreign trade provided growth of the market is declined (Aghion, et al, 2009). This thought was given by (Rehman & Serletis, 2009) who gave particular consideration to the condition of the association engaged in foreign trade relating hazard of currency. Where some important elements highlighted at the time of carrying out an examination of their co- relationship in the exchange rate and exports, while the emergence of international corporations participated in foreign trade and partners’ perspectives about the fluctuations of the exchange rate. Chowdhury (1993) investigates the impact of exchange rate volatility on the trade flows of the G-7 countries in the context of a multivariate error correction model. He observes a significant negative impact on export volume for each country. Prasad, Rogoff, Wei, and Kose (2004) find that “volatility has detrimental effects on international trade and thus has a negative economic impact, especially on emerging economies where underdeveloped capital markets and unstable economic policies exist.” Vergil (2002) investigates the impact of real exchange rate volatility on the export flows of Turkey to the United States and its three major trading partners in the European Union for the period from 1990 to 2000. The standard deviation of the percentage change in the real exchange rate is employed to measure the exchange rate volatility while Cointegration and error-correction models are used to obtain the estimates of the Cointegration relations and the short-run dynamics, respectively. The results provide evidence of significant negative effect of real exchange volatility on real exports. The Republic of Congo exchange rate sensitivity has been discussed by Molinder and Westlund (2000, p.2), where they study how Congolese manufacturing export Africa, Europe, America and Asia was affected by the exchange rates during the 90’s. The exchange rates of the trade areas are weighted, based on the shares of the individual countries’ trade with Congo. The Congolese regions’ share of manufacturing industry and branch composition determines their sensitivity to exchange rates. The share of export to each of the trade areas governs the sensitivity to changes in the exchange rates to that particular area. They conclude that changes in international demand influence Congolese exports (trade) to a higher degree rather than changes in exchange rates. Qian and Varangis (1992) apply ARCH-in-mean model to six countries in estimating bilateral and aggregate exports. They find exchange rate volatility to have a negative, statistically significant impact in two cases: Canadian and Japanese exports to the United States. In terms of aggregate exports, the relationship is negative but statistically insignificant for Japan and Australia while positive and statistically significant for Congolese and China, but statistically insignificant for the France. The magnitude of the impact of exchange rate volatility varies greatly – from a reduction in exports of 7.4% for Canada to an increase of 3% for Congo, following an 8% increase in volatility. Clark et al. (2004, p.15) argues that one reason why trade may be adversely affected by exchange rate volatility stems from the assumption that the firm cannot alter factor inputs in order to adjust optimality to take into account of fluctuations in exchange rates. When this assumption is relaxed and firms can adjust one or more factors of production in response to fluctuations in exchange rates, increased volatility can in fact create profit opportunities. This situation has been analyzed by Canzoneri et al. (1984), De Grauwe (1992) and Gros (1987). While earlier literature focused on the negative effect of exchange rate on trade, recent studies provide explanations on why a positive effect could also possible. Bailey et al. (2000) argue that in order to reduce volatility the authorities have to rely on measures that can be costlier than the exchange rate volatility they replace. De Grauwe (1987) argue that if exporters are sufficiently risk averse, an increase in the exchange rate volatility raises the expected marginal utility of export revenue and therefore induces them to increase exports. Cabalero and Corbo (1999) show that under perfect competition, convexity in profit functions, symmetric costs of capital adjustment and risk neutrality, increases in exchange rate volatility will increase exports. Their argument goes as follows: when exchange rate movements are unfavorable, firms will reduce production and thus they will have more capital than optimal. When exchange rate movements are favorable, firms will produce more and have less capital than they need. Assuming a convex profit function, the potential profits foregone due to insufficient capital are higher than the losses due to underutilized capital. So profit maximizing firms, will tend to overinvest, and thus export more in the face of uncertainty. The authors argue, however, that if the hypothesis about risk neutrality and symmetric costs (e.g., sunk costs) are relaxed then exports will decline with increasing exchange rate uncertainty (Qian and Visangis, 1992, p.2). Others, including Franke (2001), Sercu and Vanhulle (2002) have shown that exchange rate volatility may have a positive or ambiguous impact on the volume of international trade flows depending on aggregate exposure to currency risk (Viaene and de Vries (1992)) and the types of shocks to which the firms are exposed (Barkoulas et al. 2002). There are also models that study the impact of exchange rate uncertainty on trade and its welfare costs within a general equilibrium framework including Obstfeld and Rogoff (2003), Bacchetta and van Wincoop (2000) (cited Baum and Caglayan, 2006, p.2). Ambiguous and inconclusive results of exchange rate volatility impact on trade have been found across many studies. The study estimates an export demand equation using disaggregated monthly data for the period 1993 to 2001 and concludes that UK export to the EU are largely unaffected by exchange rate volatility. Morgen Roth (2000) obtains similar results while examining the case of Irish exports to Britain. Estimated error correction models by Doyle (2001), also for Irish export to Britain, reveal that both real and nominal volatility are significant determinants of changes in total exports and in a number of sectors. Both positive and negative short-run elasticities for exchange rate volatility have been estimated, although positive elasticities predominate. Wang and Barrett (2002) analyze the effect of exchange rate volatility on international trade flows by studying the case of Taiwan’s exports to the United States from 1989-1999. They found that real exchange rate risk has insignificant effects in most sectors, although agricultural trade volumes appear highly responsive to real exchange rate volatility (Todani and Munyama, 2005, p.2). Hondoyiannis et al. (2005) study exchange rate volatility issue for 12 industrial economies examining a model that includes real export earnings of oil-producing economies as a determinant of industrial-country export volumes. Baum and Fagereng (2007) examine the causal link between export performance and exchange rate volatility across different monetary policy regimes within the integrated VAR framework using the implied conditional variance from a GARCH model as a measure of volatility. While treating the volatility measure as either a stationary or a non-stationary variable in the VAR, they were not able to find any evidence suggesting that export performance has been significantly affected by exchange rate uncertainty. A number of diversity studies have been implemented regarding exchange rate fluctuations vis-à-vis different macroeconomic indicators. Jones and Kenen (1990) state that exchange rate volatility is directly influenced by several macro variables, such as demand and supply for goods, services and investments, different growth and inflation rates in different countries, changes in relative rates of return and so forth. The present floating rate has been affected by previous real and monetary disturbances. Expectations about current events and future events are also important factors due to the large influence it has on exchange rate volatility. The volatility can also arise from “overshooting” behavior which occurs when the current spot rate does not equal a measure of the long-run equilibrium calculated from a long-run model. If this behavior arises because the financial market is not working correctly, high exchange rate volatility does not have to imply high transaction costs (Backman 2006, p.3). Most economists would probably assume, for a start, that exchange rate volatility cannot have a significant impact on labor markets, given that the link between exchange rate volatility and the volume of trade is known to be weak. Belke et al. (2005, p.3) investigate in how far high exchange rate volatility can be made responsible for the negative developments in Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC) labor markets.

4. Methodology

- In this part, we will describe the models and the data used, as well as the estimation and verification procedures applied. Ø The basic ModelsThe impact of exchange rate volatility on trade is measured using two functional forms: the real export demand function and the real import demand function. These models are determined using the following variables: domestic and international inflation, the consumer price index, GDP, foreign reserves, the shares price index as a proxy for business and consumer sentiments (Tang, 2012), domestic interest rates, interest rate differentials, 3 real exchange rates, the per-unit US dollar as the foreign rate and the per-unit Congolese fca as the domestic rate, and GARCH-based exchange rate volatilities. Further, the corresponding autoregressive term allows us to capture the dynamic nature of these models and the speed at which they adjust toward long-run equilibrium in case a deviation occurs.Since exports will decrease with an exchange rate appreciation while imports will rise, mathematically, this relation is given as: X=f [1/ER per $)]

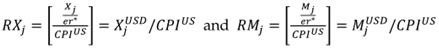

M=f (ER per $)Real exports (RX) and real imports (RM) are calculated as follows, using data on the value of exports and imports in millions of domestic currency for each country index and the price index:

M=f (ER per $)Real exports (RX) and real imports (RM) are calculated as follows, using data on the value of exports and imports in millions of domestic currency for each country index and the price index:  Where RMj = the real exports of the jth country in $ terms, X$j = the real imports of the jth country in $term, = the nominal exports of the jth country in $ terms, M$j = the nominal imports of the jth country in $ terms, CPIUS = the US consumer price index CPI)and er* = monthly average exchange rates (domestic currency per unit of USD).The exchange rate in terms of domestic currency per unit of foreign currency will be a function of nominal exchange rate and the foreign to domestic price ratio (Pf / Pd) for each country: RER = f (Pd, Pf, NER).

Where RMj = the real exports of the jth country in $ terms, X$j = the real imports of the jth country in $term, = the nominal exports of the jth country in $ terms, M$j = the nominal imports of the jth country in $ terms, CPIUS = the US consumer price index CPI)and er* = monthly average exchange rates (domestic currency per unit of USD).The exchange rate in terms of domestic currency per unit of foreign currency will be a function of nominal exchange rate and the foreign to domestic price ratio (Pf / Pd) for each country: RER = f (Pd, Pf, NER).4.1. Model Specification

- GARCH models are assumed to be appropriate for capturing news elements 4 in time-series data. They also help us understand the dynamic behavior of exchange rate variables and derive variance series for volatility.The real exchange rate usually depends on its values in the recent past and on the nonconstant variance, hence: RER = f [RER~N (0, h2)].According to the impact of autoregressive and autocorrelation elements to the exchange rate is accounted for through the first lag of the dependent variable and error terms, respectively. The conditional constraint ut (h2) indicates that any shock or noise that might exist in the error term (ut) is normally distributed with a zero mean and nonconstant variance (h2)’.

4.2. Data

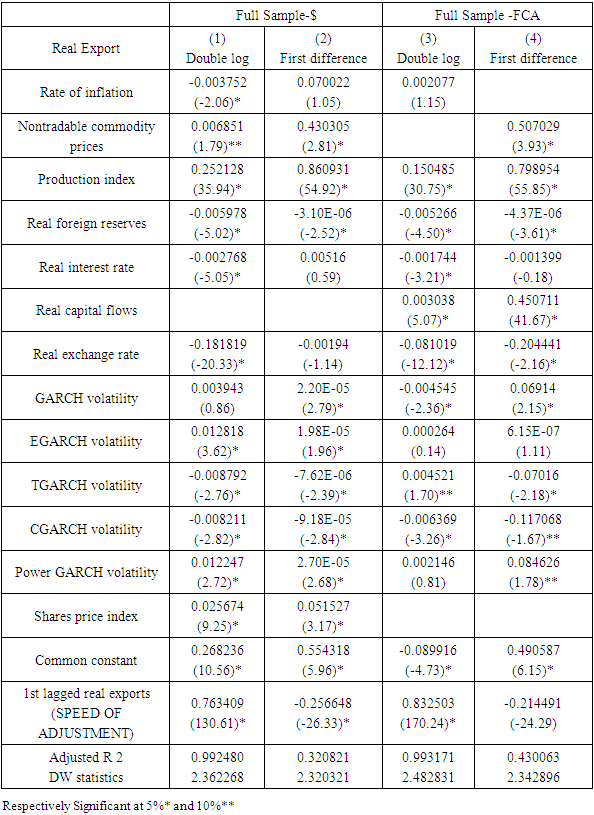

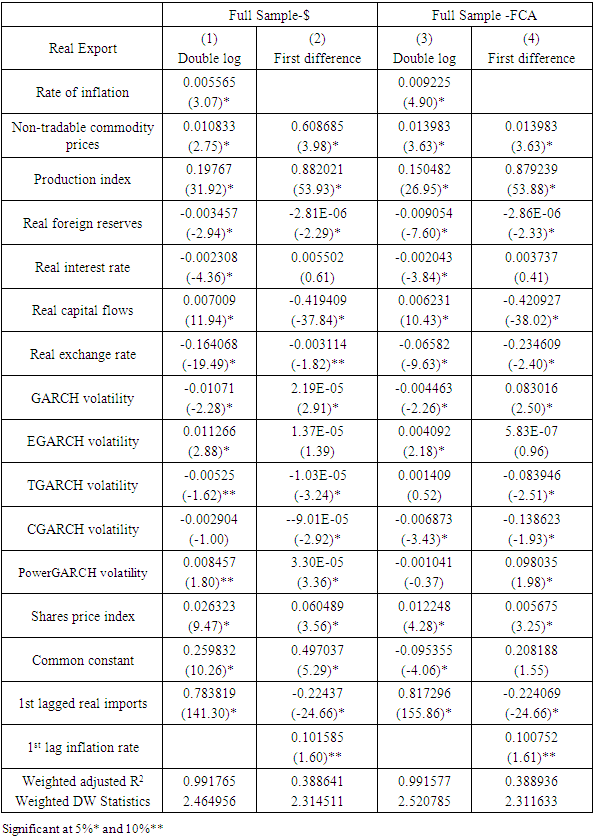

- In this paper, we chose a 20 years’ monthly data series from January 2000 to December 2019 with more than 250 values for each time series variable in particularly in the case of exchange rates. Our data came from the Congolese Ministry of Economy, department trade Statistics database. The other source of data was collected from the International Statistics Database. Regarding any missing values, we referred to the official websites of the ministry in the department of statistical office and (Heston, Summer, & Aten, 2002).The dataset we have used has both a time-series (T) and cross sectional (N) dimension (with the condition N > T where T is large). This is referred to as panel or longitudinal data.Estimation results of exchange rate impact on Congolese Trade

|

|

5. Analysis Result and Discussion

- In this paragraph, we will describe the short and long run volatility impact on the Congolese trade functions.

5.1. Long Run Volatility Impact

- After many analysis, our obtained results showed that the fixed-effects log models show that exchange rate volatility has a highly significant impact on both the real import and export demand functions. While all the sampled countries were evaluated, the magnitude of the impact and the number of significant volatility variables are larger for the foreign currency rate than the domestic rate at a 5 percent level of significance. In particular, the impact of the GARCH-based volatility variables on trade depends on the nature of volatility in the exchange rate measured by each corresponding volatility variable.Analyzing the full sample reveals that the impact of bad news is significant in the export function while a leverage effect is noted in the import function. The long-run persistence of news occurs in both functions. Remarkably, in the case of the developing countries sub- sample, all the volatility variables are insignificant except for nonlinearity in volatility, which is significant at the 10 percent level only in the import demand function. In both currency terms, the impact of bad news encourages exports in the long run when the sample countries’ mutual trade links are accounted for. In the foreign currency rate, however, the same phenomenon discourages exports in the sub-sample and imports in both samples.

5.2. Short Run Volatility Impact

- The short-run analysis reveals that volatility has no significant effect on trade when Pakistan trades only with developing countries. The robustness of this finding is established when we evaluate the developed countries in the full sample as well as separately. Both results confirm the existence of a significant volatility effect. The direction of the volatility effect differs across volatility specifications.

5.3. Volatility Specification Impact

- It relied that the exchange rate volatility impact is significant. Each model based on a particular volatility specification behaves differently.⇒ GARCH (1,1) shows that shock disturbances continue to transmit their effect in subsequent periods and cause instability in trade flows and in the expected stream of returns. Therefore, volatility clustering depresses real exports persistently both in the long run7 and the short run when we consider all Pakistan’s trading partners by using the oil currency. ⇒ The EGARCH-based leverage effect and dominant shocks lead to an increase in real exports when using the vehicle currency as a whole. However, in the short run, real exports decrease among underdeveloped partners and remain completely insignificant when using the domestic rate. In the short run, imports among all the sampled partners are encouraged in terms of both rates. However, among underdeveloped partners, we see no volatility effect on real imports when using the domestic rate; the effect significantly discourages imports in the short run and encourages them in the long run. ⇒ TGARCH-based asymmetries and the impact of bad news discourage real exports among all partners when using the vehicle currency (foreign rate). This also applies in the long run to underdeveloped partners. Using the domestic rate encourages real exports in the long run only but with no effect otherwise. Real imports are discouraged among all partners but with no effect in the case of most underdeveloped partners when the domestic rate is considered. ⇒ The CGARCH-based long-run persistence of news discourages real exports in both the long and short run when using the vehicle currency for all partners. However, when Pakistan trades with underdeveloped counterparts, real exports are encouraged in the short run but discouraged in the long run. Underdeveloped trading partners remain immune in domestic rate terms. Real imports are discouraged irrespective of the partner in the short run. In the long run, we see no effect except when the domestic rate is used.⇒ NGARCH-based nonlinearities generally encourage real exports except among underdeveloped partners in the short run, which remains unaffected alike domestic rate in all cases except in short run when it encouraged real exports for all partners in short run. Real imports increase in the short run for all the sampled countries as well as in the long run within the underdeveloped partner sample. Otherwise, there is no effect.

6. Conclusions and Suggestion

- This paper has an empirical investigation of trade impact of exchange rate in Congo from the analysis of trading partners. In the presence of conflicting and ambiguous findings of prior studies, the purpose of this study was to determine the impact of exchange rate trade on Congolese partners. Using the country’s own currency to conduct trade transactions by excluding the developed trade partners helps avoid volatility distortions. This implies that the volatility impact may emerge when considering trade with developed trade partners and when the foreign currency is involved.10 These results are in line with Esquivel and Larraín (2002) and Mustafa and Nishat (2004). We can conclude that volatility might not reside purely in the vehicle currency but can also be transmitted from developed countries’ financial markets through trade links. Hence, we can justify the first hypothesis and provide evidence on the existence of Cushman’s third-country effect.On average, most exchange rate volatility variables remain significant when the oil currency is employed to conduct international transactions related to real exports among all the sampled partners. However, when only underdeveloped partners and the domestic rate are considered, volatility has no effect on real exports. The proliferation of financial hedging instruments over the last 20 years may reduce firm’s vulnerability to the risks arising from volatile currency movements. Consequently, insignificant impact of exchange rate volatility on export and import for Swedish market might be explained by existing hedging possibilities for exporters and importers via futures and/or forward markets (Clark et al, 2004). The results deviate from Hayakawa and Kimura (2008) perhaps because we have used domestic currency-based exchange rates. As in the Republic of Congo, a large number of developing countries have trade concentrations with developed countries. A recent economic survey suggests that the global economy is passing from a unipolar (US) economy toward emerging economies. In the future, such structural changes in trade patterns may help avoid potential volatility distortions. In conclusion, Congolese clearly needs to revise its trade policy and expand trade with low- and middle-income developing and emerging economies, using its own domestic currency to avoid the uncertainties and related instability of exchange rates. These uncertainties can emerge through the use of international currency in bilateral trade transactions because a variety of latent patterns in exchange rate volatility are potentially channeled through the vehicle currency.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML