-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Tourism Management

p-ISSN: 2326-0637 e-ISSN: 2326-0645

2020; 9(1): 24-33

doi:10.5923/j.tourism.20200901.03

Received: Aug. 14, 2020; Accepted: Sep. 6, 2020; Published: Sep. 15, 2020

Upscaling Tourism Product Development for Enhancing Local Livelihoods at Dunga and Miyandhe Beach Destinations in Kisumu City, Kenya: A Co-Production Approach

Fredrick Odede, Patrick Odhiambo Hayombe, Stephen Gaya Agong, Fredrick Omondi Owino

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology (JOOUST), Bondo, Kenya

Correspondence to: Fredrick Odede, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology (JOOUST), Bondo, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Ecotourism is emerging as an alternative development path that can enhance environmental conservation, promote participation and collaboration of various stakeholders towards achieving sustainable livelihoods along the Lake Victoria beaches as fishing and fish by-products can no longer meet the current livelihood needs. The aim of this paper was to establish the way forward on how different stakeholders would participate and collaborate towards ecotourism product development process. Exploratory research design was used to guide the study in realizing its objectives. A Triple Helix framework (academia, community members, private sector and county government) was adopted in attaining full participation of all the stakeholders. Data collection techniques included Focus Group Discussion (FGD, oral interviews and observations. The data was analyzed using thematic analysis based on the study objectives. The study findings pointed out that Dunga and Miyandhe beaches have greater potential for ecotourism although they are facing several challenges (poor infrastructure, inadequate community members’ involvement, insecurity among others), a situation that can be changed through creation of participatory and collaborative approaches. There was evidence of ecotourism products (fish, birds, Hippos, board walk, historical sites, dances and trades); and stakeholders (fisher folk, Beach Management Units (BMUs), the hotel industry, local community members, national and county governments, and Non-state organizations–Kenya Ports Authority, and Kenya Maritime Authority (KMA) indicating the potential for realizing the goals of this exercise. The FGDs were eye openers and there is need to build a network system between the stakeholders, unite resources with the goal of promoting ecotourism management within Dunga and Miyandhe beaches and their environs. When stakeholders from Dunga and Miyandhe sites came together, their opinions on the benefits of ecotourism were realized. The outcomes included habitat destruction, unemployment and job creation, insecurity and security, drug and alcohol abuse, awareness and knowledge enhancement on how best to protect and conserve the lake resources. The recommendations for future ecotourism development of the beaches were to improve road infrastructure; construction of site facilities; improvement of information centers; establishment of standard hotels, making of standard tour boats and rescue boats; improvement on health facilities; employing trained divers; improvement of beach environment, and the need to establish networks, collaborations, partnerships and sharing of ideas.

Keywords: Product Development, Participatory, Collaborative, Ecotourism, Development, Product, Dunga, Miyandhe, Beaches, Lake Victoria

Cite this paper: Fredrick Odede, Patrick Odhiambo Hayombe, Stephen Gaya Agong, Fredrick Omondi Owino, Upscaling Tourism Product Development for Enhancing Local Livelihoods at Dunga and Miyandhe Beach Destinations in Kisumu City, Kenya: A Co-Production Approach, American Journal of Tourism Management, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2020, pp. 24-33. doi: 10.5923/j.tourism.20200901.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Ecotourism is persistently becoming a significant topic in the tourism industry (Weaver & Lawton, 2007). It is recognized as a sustainable way to develop regions with abundant tourism resources (Weaver, 2011) and it remains the future hope for many developing countries since agriculture which has been the mainstay economic activity is experiencing adverse effect of climate change (Hayombe, Agong, Maria, Mossberg, Bjorn & Odede, 2012). Environmental resources are steadily declining, and fish resources in the Lake Victoria (where Kisumu City is located) are no longer guaranteed to support sustainable livelihood (Hayombe et al., 2012). Tourism means different things to different people (Jafari, 1990). Ceballos-Lascurain (1996) defined ecotourism as travelling to relatively undisturbed or uncontaminated areas with the specific objective of studying, admiring, and enjoying the scenery, wild plants and animals, as well as any existing cultural manifestations (both past and present) in such places. The International Ecotourism Society (TIES) (2006) defined ecotourism as responsible travel to relatively undisturbed areas for purposes of education, conservation and improvement of local people’s well-being. While Ceballos-Lascurain placed more emphasis on the motive of the tourist, TIES emphasized conservation and welfare of the local populace. One useful approach to the study of tourism phenomena is to focus on tourism destinations. These are geographic locations where tourists spend most of their time when travelling. A destination contains “a critical mass of development that satisfies the traveler objectives” (Baggio, 2013), thus offers a tourist the opportunity of taking advantage of a variety of attractions and services. Many scholars consider it a fundamental unit of analysis for understanding the whole tourism phenomenon, even if difficult to define precisely and problematic as a concept (Framke, 2002).The strong emphasis on the local community, such as conserving local resources and increasing local benefits, highlights the close association between ecotourism and local residents (GoK, 2007). Residents, one of the essential stakeholder groups (Zhang & Lei, 2012), play a key role in ecotourism as their participation contributes to distinguishing quality in tourism management (Drumm, 1998). The success of ecotourism depends on a harmonious relationship between residents, resource protection and tourism (Ross & Wall, 1999). However, obstacles remain such as the top-down decision-making process, which overlooks the importance of residents’ opinions (Byrd, 2007). Insufficient knowledge on sustainable resource utilization on the part of the residents lead to their distrusting interpretation of ecotourism as an attempt to restrict their use of local resources and traditional activities (Ross & Wall, 1999). Engaging residents in ecotourism management not only facilitates their comprehension of local tourism (Byrd, 2007) but also improves the quality of planning and decisions by incorporating the locals’ views (Owino, Hayombe & Agong 2015; Owino, 2016; Carmin, Darnall, & Mil-Homens, 2003). It is for this reason that this study involved different stakeholders in a participatory and collaborative ecotourism development process for Dunga and Miyandhe beaches of Lake Victoria, Kenya. The knowledge on the importance of wetland is crucial in ecotourism promotion (MacHaria, Thenya & Ndiritu, 2010) because when residents learn about the value and importance of wetland, their environmental behavior is expected to shift to pro-wetland. Dunga Beach and Wetland is known for its unique eco-cultural attractions due to its rich biodiversity, cultural heritage and diverse papyrus wetland ecosystem. Dunga swamp is an Important Bird Area (IBA) – a place of international importance for bird conservation covering 5000 ha located at Dunga at the Tako River Mouth. The area is a wetland situated about 10 km south of Kisumu town on the shores of Winam Gulf, Lake Victoria (Wanga et al., 2014). Kenya has established Dunga Wetland Pedagogical Centre at Dunga Beach as a grass-root led intervention whose overarching goal is empowerment of Dunga Wetland Community and improvement of livelihood security of its people. Therefore, some of activities in the center are promotion of Eco-Cultural Tourism and facilitation of the conservation of Dunga Papyrus Wetland Ecosystem.Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology (JOOUST) has initiated the process of strengthening Miyandhe Community Based Tourism (MCBT) by proposing the construction of modern Eco-Facility at Miyandhe beach for ecotourism ventures and opening of the interior tourist sites. The project team engaged the community at Miyandhe in demonstration of fish cage farming, within Lake Victoria, a project funded by JOOUST income generating activity. The fish cage farming has been a success story where fish harvesting and supply is provided to the community and other traders as far as Kisumu town. The community has picked this prototype and two more sites of fish cage farming have been established within Miyandhe Beach neighborhood. This has made the land value at Miyandhe to appreciate in anticipation for further development and uptake of cage fishing and eco-facility development (FDG, July, 2019).There have been prototypes at Miyandhe and Dunga beaches triggering development in their respective neighborhoods with more activities and infrastructure development proposed as well as more eco-ventures to be established. Due to the eco-tourism potential of Dunga and Miyandhe beaches, there was need to link Dunga and Miyandhe beaches in order to provide a wider range of goods and services for eco-tourism. An ecotourism consultative workshop was held to act as an exchange event that presented an opportunity for success stories from each beach. The connectivity between the two beaches would lead to an enhancement of income generation to the surrounding communities. In order to achieve these goals, FGD for various stakeholders were held to identify: the foreseen ecotourism product /goods and services; those to be involved in ecotourism within the beaches (Stakeholders); the foreseen challenges to ecotourism; and the foreseen effects/impacts/consequences of ecotourism within Dunga and Miyandhe beaches.

2. Theoretical Framework

- Participatory and Empowerment ModelParticipation is an old term used not only in tourism but also in other study areas as well as by the general public. In 1969 the Skeffington Report defined public participation as “a sharing action to formulate policies and proposals” whereas Brager and Specht in 1973 gave a more complete definition of public participation: “the means by which people who are not elected or appointed officials of agencies and of government influence decisions about programs and policies which affect their lives”.Participatory models of development have a dual focus, because they seek to achieve some specific development referred to as an outcome and evaluated by “outcome indicators”, and to empower communities via participation, referred to as process, and evaluated by “process indicators”. Evaluation of outcomes can be undertaken by observation of results such as tourism activities and improved standard of living (Morris, 2003). Participatory tourism planning includes two aspects: involvement of locals in decision making and involvement of locals in benefits from tourism. This author does not explicitly make reference to local participation in other stages. This study aimed at involving the locals at all levels of sites’ product development, management and conservation from inception, planning, development and implementation as well as monitoring and evaluation.In the 1970s some critique on tourism development was brought forward mainly due to the negative impacts that it can bring to a destination (Scheyvens, 2002). At the same time neo-populist approaches to development emerged, which held that bottom up, rather than top-down, development is preferred. Development became more about empowerment of communities through knowledge, skills and resources. Neo-populist approaches stressed the importance of an increased role of civil society in tourism development, rather than it being market led, or state controlled (Scheyvens, 2002). This thought brought forward the idea of sustainable tourism. Because the local population is in control, they decide which cultural traits they share with their guests. Community members are often the best to judge what is best for their natural surroundings. The small scale character of cultural tourism also means that small amount of tourists are visiting and therefore do not cause over-crowding of the socio-cultural and natural environment.Chanan (2000) suggests that within a community, members will choose to or otherwise become involved at different levels in an activity project or program and that the numbers of involved people will decrease as the levels increase thus creating a pyramid. However, all parts of the pyramid must be supported as they depend on one another and such support will allow all people in all possible entry points. In proposing his pyramid, Chanan states, “the higher’’ levels, such as representing the community in a scheme, rest on the lower’ levels, such as cooperation between organizations.” Bryman (2008 p.60) states that, community-based tourism development would seek to strengthen institutions designed to enhance local participation and to promote the economic, social, and cultural well-being of the popular majority’. CBT is innovative tourism development in local communities, involving individuals, groups, small business owners and local organizations and governments. Chanan (2000) further discusses that it is crucial to support the community sector generically to aid community involvement. He states that it is important to support engagement processes by maximizing participation at a full range of levels at the same time. Local participation could be the key tool for finding a balance between cultural tourism development and the local people’s livelihood. The best way of checking if this could be a solution to poverty reduction is looking at one destination where local participation is being used. Many of the CBT projects in Asia started with the prospect of economic gain; they are frequently led by the initiator, which is often one person or group; cultural heritage as well as natural environment is the main attractions for tourists; CBT creates employment opportunities for marginalized groups; and finally, cooperation between corporations and local communities is stimulated. Two elements are thus of importance for CBT projects: on one side local participation or even initiation, and on the other side economic, social and environmental sustainability. In ensuring effective participation, a triple helix approach involving key stakeholders such as the Academia (University), Public Sector, Private Sector, and Policy Makers-State (County and National Government) was enforced for an all-inclusive realization of sustainable development of the sectors involved in cultural heritage product development and promotion through the established collaborations, partnerships and networks.

3. Approach and Methodology

- Exploratory research design to guide the study in attaining its goals. This research design took a qualitative approach of data collection over a three-month period. Key informant interviews, Focus Group Discussions (FGD) and observations were used as data collection techniques to collect information. The Triple Helix framework was adopted to promote a collaborative and participatory process by engaging relevant stakeholders to achieve ecotourism product development process. The Triple Helix framework is an analytical construct that systematizes the key features of: Academia (University); Public (Industry; and State (County and National Government) interactions into an “innovation system” format defined according to system theory as a set of components, relationships and functions. FGD was employed to establish the objectives of the study. Participants from: Kisumu Local Interaction Platform (KLIP), JOOUST, Kisumu County Government, community members from Dunga and Miyandhe Beaches were involved.The study used key informants to obtain in-depth information from the host communities around the attraction sites. In-depth interviews with key informants were conducted to get an understanding of the subject matter under investigation. Face-to-face interview with appropriate respondents yielded credible research data. The instrument was used to follow-up questions during discussions to provide specific responses and to ensure that the discussions did not go outside the topic of the study. The respondents included County Director of Tourism, County Director of Culture; the CEO Lake Victoria Tourism Association; Chiefs, Curator of Kisumu Museum and the coordinator of Cooperative groups, county government officials, leaders of private sector cultural tourism enterprises, and beach management officials.Oral interviews are direct face-to-face attempt to obtain reliable and valid measures in the form of verbal responses from one or more respondents. According to Orodho, (2003), interview is a set of questions that an interviewer asks when interviewing a respondent. Interviews provide reliable, valid and theoretical satisfactory results. Interview schedules were designed to suit the informants in this study.A FGD guide was developed focusing on working with members of tourism organization; existing tourism potential; existing opinion on tourists and the social impacts of tourism; infrastructure and public service; natural and cultural resource; and stakeholder recommendations. The authors moderated the discussions to ensure that the participants remained focused on the themes under consideration. Contrary to interview and questionnaire, FGD is inexpensive because the investigator meets the respondents at one venue (Ghauri & Gronhaug, 2010). All participants were divided into four different groups. This was done by first identifying the number of participants from Miyandhe and Dunga. They were then made to identify with numbers 1, 2, 3 and 4 respectively. The same identification was done to the remaining participants. This was to ensure that there is diversity and representation of community members from both Miyandhe and Dunga beaches in every group. It also ensured control of biasness on group identity. All members having the same number identity were grouped together for example; members with number 1 identity were made to belong to group one, while those with number identity 2, 3, and 4 were made to belong to group two, three, and four respectively. General tasks were given to each group as follows: group one – identifying tourism products/goods and services; group two – identifying tourism stakeholders; Group Three – identifying challenges to tourism; and group four- identifying effects/impacts/consequences of tourism. The group members then discussed specific questions under the following themes: existing tourism potential; existing opinion on tourists and the social impacts of tourism; infrastructure and public service; natural and cultural resource; and stakeholder recommendation. The analysis of information attained from the FGD was analyzed using thematic analysis where qualitative features were adopted.

4. Community Management Strategy for Sustainable Use of Natural and Cultural Resources

- The participants felt that there is a strong link between tourism and natural/cultural resource protection. There are natural and cultural resources managed currently within the two beaches, which is done by KWS, fisheries, National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), and BMU. The communities were involved in the management of resources based on the development plans for the sites. They believed that community members needed more involvement in management of resources in order to control the utilization of the resources. This is to ensure sustainability of the projects. This approach is supported by Drumm (1998) who says that local residents play a key role in ecotourism as their participation contribute to distinguishing quality in ecotourism management. Dunga and Miyandhe sites are some of the most reliable destinations in Kenya for the scarce and threatened papyrus yellow warbler. Dunga is part of the Nanga region and is an informal settlement with rural character (Hayombe, Agong, Nystron, Malber & Odede, 2012; Falted, Reddin & Wanga, 2012). Numerous endemic bird species characterize the adjacent wetland, creating an attractive destination for educational tours. The wetland is predominantly papyrus thus creating a distinctive habitat for papyrus specialist birds such as the Yellow Warbler, which is very hard to find in other areas of Kenya. Eight of Lake Victoria Basin biome species have been recorded here. It is especially important for all papyrus endemics Papyrus Gonolek, White-winged Warbler and Papyrus Canary, Carruthers’s Cisticola (Falted, Reddin & Wanga, 2012). Other notable wetland birds found on these sites include the kingfisher, little egret and hammer kop (Plate 1).

| Plate 1. Wetland Birds in Dunga Established via 2019 Field Survey |

| Plate 2. Hippo swimming in Lake Victoria, Dunga, Kisumu Established via 2019 Field Survey |

| Plate 3. Water Hyacinth |

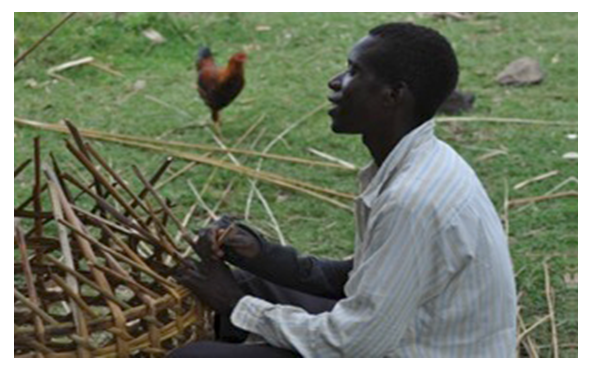

| Plate 4. Basket making at Dunga |

| Plate 5. Stakeholder Consultative Discussions |

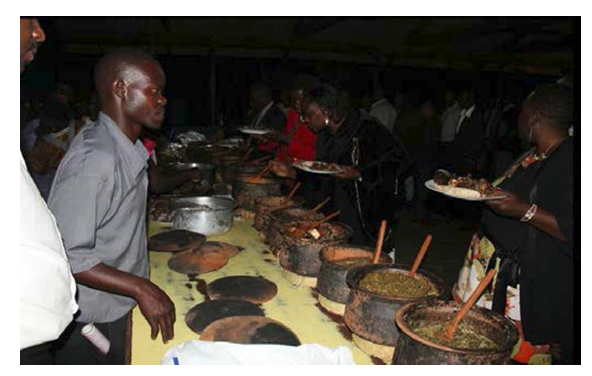

| Plate 6. Traditional Foods Sampled During the Dunga Fish Night, Source: Wanga, 2014 |

5. Dunga and Miyandhe Ecotourism Products, Goods and Services as Destination Packages

- Tourism products and experiences may be considered as collections of components such as accommodation, transport, attractions, hospitality among others. The relationships between these different elements are difficult to define and analyze in aggregate form due to the variability in which different customers arrange them throughout their trip (Baggio, 2013; Wanga, Hayombe, Onyango and Agong, 2014). A product can be defined as something that is: an offering; has value; can be bought; tangible/intangible; natural, man–made. In terms of ecotourism, a product is an offering to a tourist that has value attached to it and can be bought, tangible (Goods) intangible (services), man-made or natural (Otiende, Ayieko, Hayombe & Agong, 2015). The product can be developed through: value addition; accessibility; capacity building; and creation of awareness. Some of the products identified for the joint collaboration of the two beach destinations were: fishing; the board walk; bird watching; boat branding; community work (in the Dunga village); narrations; Hippo watching along the Lake Victoria shores; water-sport; Dragon boat race; sport fish; curios and artefacts, arts; culinary ecotourism; filming and photography; cultural ecotourism; homestays; fish cage farming; fish eating festival; Oyamo island (declension Centre for freedom fighters) and (bird watching); Peninsula (Hungwe hill) geographical formula. The requirements for these product development were accessibility by creating well- maintained roads; stakeholder involvement in ecotourism product development at all levels; provision of social amenities, availability of credit facilities from banks, construction of health facilities like hospitals; promotion of capacity building of community members and other stakeholders; identifying potential for sustainable utilization; development and improvement of infrastructure; establishing legal frame-works; enforcing and ensuring safety and security within and around the sites; promotion of the products through marketing and branding; community awareness creation for appreciation of the values of these sites; and the presence of Dunga and Miyandhe beaches. The products that can be sold or offered to the tourists are: water sport (boat raising dragon boat race for both beaches); sport fishing; cultural artifacts of arts; culinary tourism (food) with fish as main delicacy; home stays; fish cage farming (both Dunga and Miyandhe); fish eating festivals; colonial heritage at Oyamo island (where Mau Mau fighters were held hostage); war cells at Hungwe hill; and associated social amenities like banks, and hospitals. Interaction can be between the tourists and guides, the local communities and physical surroundings as well as other tourists, which are crucial in the designing of experiences and packages (Eide & Mossberg, 2013). Inviting the tourist to participate in the experience is believed to give extra value as opposed to only passively watching. “To participate is vital, if one wants to understand the tourism experience. It is different from just sitting passively and watching” (Eide & Mossberg, 2013). These interactions at Dunga and Miyandhe beaches should create relationships and emotional bonds, as well as valuable memories. This is not so much about what the guides know as it is about the feelings and values they embody and communicate (Arnould & Price, 1993, p 34). It affirms the important role of local guides in understanding the tourist’s perceived value (Otiende, Ayieko, Hayombe & Agong, 2015; Mossberg, 2007).In Dunga, there are possibilities for several types of packages that can satisfy the needs of different types of tourists. This can be used as the overall theme and storytelling when designing the packages. Packages can also be used to connect different stakeholders with each other. Many ideas have come up on how to work on culture packages such as the local history of Dunga in promoting tourism at these sites. This includes the stories of Dunga and Miyandhe’s background and the people that have lived in these places. It can include stories about early Indian settlers who came to work for the British government in building the railway, to later settle down as fishermen at Dunga. This story is connected to the word Dunga as an old Hindu word for “deep water” or a “deep place”. Physically, this can connect to some of the old structures that might still stand from that time as well as to the railway. Culture packages can also be about the Luo culture. For example, there have been suggestions about a “Luo culture package”, a package that could be between one hour and a full day. The first part can be an introduction of the early settlers, which would later continue with the Luo culture. The tourists can be directed through a trail along the beaches and in the villages, where they visit Luo homesteads and get to listen to related stories. Another similar idea is a one day package called “community homestay”, where the tourist gets the opportunity to learn about the local culture and its traditions by participating in the daily activities and experiencing of Dunga and Miyandhe lifestyle (Awuor, Ayieko, Hayombe & Agong, 2015). They get to experience a boat ride, where they can fish, which they later on can participate in cooking. The package also includes enjoying local folk tales and dances such as Ohangla and Sigio that are used to express the good deeds and experiences in the community. The tourists can even learn some of the local language (dholuo). The tourists can have a feel of how to live in a traditional homestead, and how the traditional homesteads are planned, built, as well as their spatial organization and use. This could also be complemented with other tourism products such as traditional foods, cooking, utensils or a recipe book of traditional recipes.The participants that worked with ideas on culture packages thought that packages around Luo culture can attract both international and domestic tourists. People who are not aware of Luo culture or those who live in the vicinity might, for example, find it valuable to experience a more traditional village lifestyle. There are many opportunities to connect packages to Lake Victoria. One idea is a “lake package” or “gulf ride package”. It is a two to five day boat trip that starts from Dunga to Miyandhe and ends back at Dunga where the tourists can fish, cook their own food, camp on beautiful beaches and islands of the lake. The trip can end up with a festive evening in Dunga beach marked by traditional Luo music and dances. The ride starts off from Dunga and heads to Ahery for activities such as bird and hippo watching, as well as fishing activities. It can briefly stop for a picnic in the Nyamware area where they are able to watch the sunset and hear stories about the famous Luanda Magere warrior to wrap up the first day’s activities. The second day can start at sunrise, with a walk along turbine water. In the evening they can camp at the campsite on the Kisiege beach, where they can be entertained by the famous Ohangla music dancers from the area. In the evening, the visitors can be treated to stories of the warriors of south Nyanza such as the mythical narrative of Nyamngondo. On the third day, they go for a fishing trip to Moboko island, a place laced with beautiful lake scenery. Moboko is home to several wild animals (monkeys, indigenous species, crocodiles), and a good vintage point for sunset viewing from the peak of the mountain at Moboko Island. The tourists can spend a camping night where they are entertained by tour guides. Day four takes the tourists on a long journey through several beaches to Miyandhe beach while experiencing and sight-seeing different lake islands and scenic lake features before landing at Miyandhe beach. On day five, it is time to return to Dunga beach, and on the way for they experience almost the same attractions and events but also the old railway line, the hippos, crocodiles, and old harbors. It is imperative to mention that Dunga and Miyandhe provide a unique connectivity for cruise tourism where tourists can have experiential feel of the various scenic attractions in Lake Victoria as well as the lifestyle of the fisher-folk communities living in and along Lake Victoria. Cruise tourism would connect Dunga with other beaches along Lake Victoria before arriving at Miyandhe and back to Kisumu city. Dunga events include several activities that Dunga beach can host. One event, a Fish night, has already been held that is a good example (Beth et al., 2018). The tourists are encouraged to write down their reflections about this event, what went really good and what can be improved during future events. One event idea that come up was that of a “Dunga Ecotourism Lake Day” that can attract the local communities from Kisumu City and other tourists, with the purpose of sensitization about ecotourism to the communities. Such an event can strengthen the identity of Dunga and Miyandhe beaches as tourism destinations. The event could also be an avenue for marketing other tourism activities and packages in Dunga and Miyandhe. During the event, one can display and sell local crafts that are made of local material such as water hyacinth, or showing the Luo culture. There could also be expert speakers on ecotourism and a local theatre group can act and tell stories about the wetlands and Lake Victoria. There could also be some more active activities such as a tug of war. The event should be eco-friendly since Dunga and Miyandhe are ecotourism sites, which could be a good event for trying out new litter bins, and perhaps even more conservation strategies such as bottle recycling (Otiende et al., 2015; Wanga et al., 2014). It could be an annual event, whose entrance fee charges that are collected could be used to sustain the sites. Other ideas that have come up are culinary days, where the visitors can sample different types of traditional foods and delicacies like tilapia, dengu, osuga etc. Such an event could generate revenue through entrance fee charges or income to the locals when visitors purchase cultural items as well as pay for food services. Other events that target the younger generation like kids, and the youth in the form of storytelling, singing, dancing, drawing, ball games, bouncing castle, and environmental studies would diversify the products and services being offered to visitors hence ensuring its sustainability. Another thing that came out during FDGs was the annual boat race that might be held at Dunga and Miyandhe beaches. Capacity building and guidance on the various product development initiatives will target marketing activities of products such as basketry, fish festival, bird watching, hippo watching, boat riding, bird watching, kalanywena (sport crocodile), sport fishing, and boat-rowing competitions. The cultural products to be exploited for these beach destinations include: Dunga and Miyandhe–water sports, traditional dances, Luo homestead, story-telling, and camping facilities.

6. Effects, Impacts and Consequences of Tourism Promotion at Dunga and Miyandhe Destinations

- The identification of foreseen impacts and consequences for the collaboration is a motivation to what is expected to be beneficial to all parties in the collaboration. Some of the effects were: proper training of the locals’ tourist guides on skilled handling of the customers in hospitality industry. Conservation of natural wetland plants from human activities that are threatening the survival of this natural habitat (through cutting and burning of papyrus reeds). Improved sanitation and water supply in the sites to reduce poor health conditions resulting from bad hygienic practices. Reduction of water pollution by reducing poor farming methods, and preventing soil erosion to control siltation of the beaches as well as clearing of hyacinth weeds. Establishment of proper site infrastructural facilities through the construction of hotels, toilets, boats, electricity, water, information centers, site signages, and roads. Implementation and enforcement of governmental policies, specifically cultural heritage and tourism policies, as well as, provision of administration services by improving security and safety of these place destinations. Improved marketing and branding strategies such as hosting of cultural events and exhibitions, hosting or participation in cultural festivals, participation in national and international trade fairs, use of internet and websites, publications, brochures, and documentaries. Proper planning of the space to check and human encroachment and growth of informal settlements at the beaches. Creation of employment opportunities for disadvantaged groups and less fortunate members of the society such as youth, women and the disabled through eco-venture initiatives such as basket-making, pot-making, artistic works, sporting activities and traditional dances and songs. Establishment of collaborations, networks and partnerships for an all-inclusive, participatory and co-production methods of realizing the goals of product development activities for tourism promotion of the beach destinations. Working together with policy makers in promoting tourism and cultural heritage in the sites to ensure budgeting appropriations for ecotourism and cultural heritage ventures. Good visibility of the potential and challenges of the tourism destinations by presenting them to the general public. Increased tourist numbers visiting the sites due to high visibility supported by diverse tourism attractions. It will act as a source of revenue generation that can trigger of other development programs and support sustainable development of the affected areas where the sites are located. Income generation through self-employment creation to support local livelihoods of the host communities.The expected impacts and consequences of tourism product development include up-scaled benefits as a result of tourist accessing the sites and related emergency facilities. Personal grooming i.e. dress code; and establishment of training facilities since the cost of training is high; improved living standards among the locals; employment of the locals; development of the sites such as hotels, roads, board walks, car park, cultural information and electricity supply; knowledge of most sites leading to more tourists attraction; creating openings to donors to invest in tourism ventures, improved prices on tourism products; enhanced cultural heritage preservation; improved wildlife conservation strategies; increased cultural events (boat racing and Dunga fish night); improved social and cultural interaction such as marriages, recreation, sport, scenery view and fun-fare events. For Dunga beach, there is economic gain through income generation from the ecotourism site. Ecotourism activities promote environmental conservation of the sites. Different groups come together and interact with each other and the surrounding environment as a social component. For Miyandhe, there is economic gain such as income generation, employment creation and social component that boosts the livelihoods of the poverty stricken local populace in the vicinity. Negative impacts include unfriendly encounters with the tourists through language barriers; high land carrying capacity due to numerous tourists in limited space within the sites; bad influence on the local populace such increased prostitution, indecent dressing, and alcohol and drug abuse. Some of these are social, environmental and economic benefits within and around the sites. These are able to support local livelihoods while demanding sustainable utilization of these heritage destinations for their conservation, as well as community empowerment.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Some of the identified future suggestions for future ecotourism development of the communities around the beaches were: improvement on road infrastructure; site facilities to be constructed; improvement of information center; construction of standard tour boats and rescue boats; improvement on health facilities; deployment of trained divers; and improvement of beach environments. The other related forms of development that would benefit the local residents more than tourism are: use of standard boats and establishment of hotels to be managed by BMU and the host communities. The participants agreed that there is need to establish collaborations with stakeholders in other tourist destinations through networking and sharing of ideas. There were those who knew cruise tourism and those who did not. Those who knew cruise tourism concept did so through different sources such as academic forums, and internet. They found cruise tourism to be possible between Dunga and Miyandhe beaches. They affirmed the need to train the locals on management of tourism resources and the sites through joint seminars, knowledge sharing and workshops. Branding and marketing of tourism products and resources were crucial in promoting tourism products and services for sustainable development of Kisumu city and its environs. The resources to be given priority for branding and marketing are fish, honey, fruits, herbal medicines, cultural dances and boat safaris.There are many challenges such as water hyacinth, weather, and diseases. Product development should be seen through an angle where it can be managed. The lake should be used and developed by creating a product out of it. The lake is a shared resource therefore its challenges and opportunities should be discussed widely through local participation and cultural practices. This would encourage streaming of ecotourism in both beaches. The collaboration is focusing on what can join the two beaches such as the lake and its resources, community members’ benefits, technological advancements, challenges of developing products, changes to be brought about by ecotourism, and those to be made on the various ecotourism sites. There is need to adopt BMUs as an entry point and to create ideas that are action oriented and can be implemented.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The Authors of this paper wish to thank all the participants during the study, fieldwork, and workshop, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology (JOOUST), and Kisumu Local Interaction Platform (KLIP) secretariat for their various support and participation, which contributed to the success of this study. We further appreciate the support from Mistra-Urban Futures (M-UF)/Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) that has enabled ecotourism to become an important component of urban sustainability initiative in Kisumu city. Their active support, participation and discussion contributed greatly to the success of this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML