-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Tourism Management

p-ISSN: 2326-0637 e-ISSN: 2326-0645

2020; 9(1): 1-18

doi:10.5923/j.tourism.20200901.01

Exploring Factors Influencing Employee Turnover in Saudi Arabia’s Hospitality Industry

Zeaid Mohammad Masfar

MBA

Correspondence to: Zeaid Mohammad Masfar, MBA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The hospitality industry in Saudi Arabia faces the problem of high employee turnover. This study investigated factors that contribute to the high rate of employee turnover, that is, job-related factors, organizational factors, and individual factors. The study adopted primary research methods and collected data via questionnaires. A total of 140 respondents from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s hospitality industry participated in the research. Results indicated that combinations of the aforementioned factors are responsible for the high rate of employee turnover. Also apparent is the young age of the employees who seem to leave the industry before they reach the age of 30. The results also indicated the need for further research, especially comparative studies to add information to existing literature on the subject.

Keywords: Culture, Hospitality, Turnover

Cite this paper: Zeaid Mohammad Masfar, Exploring Factors Influencing Employee Turnover in Saudi Arabia’s Hospitality Industry, American Journal of Tourism Management, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2020, pp. 1-18. doi: 10.5923/j.tourism.20200901.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Price (1977) described turnover as, “the ratio of the number of organizational employees who have exited the firm during a given period divided by the average number of employees in the organization during the same period”. On the other hand, Abassi and Hollman (2005) described employee turnover as the rotation of workers around the labour market; between firms, jobs, & occupations; and between the different states of unemployment and employment. Research has indicated that the hospitality industry experiences one of the highest levels of employee turnover when compared to any industry worldwide. The global turnover rate in the hospitality industry ranges from 60% to 300% annually, a far higher figure in comparison to the 34.7% reported in the manufacturing industry (National Restaurant Association, 2017). Due to its prevalence, the turnover culture has become accepted within the hospitality industry, with hotels regarding the issue as a work-group norm and employees frequently holding the belief that jobs in the sector hold limited opportunities for career development (Iverson & Deery, 1997). Employee turnover is a subject under the scrutiny of many scholars; research on employee resignation dates back to 1925 (Hom et al., 2017). While many researchers focus on the definition, others extend the study to classification whereby employee turnover occurs through voluntary or involuntary action. Involuntary turnover reflects the employer’s decision to terminate the employment relationship with an employee. Voluntary turnover occurs when an employee chooses to leave the job despite the employer’s willingness to keep engaging him/her. There are two ways that businesses look at turnover. The first is desirable turnover, which is the result of incompetent employees exiting the firm. Workers who cost the firm through mistakes or a series of poor choices belong in the desired turnover category. Any exposure to legal or financial risks, a threat to assets, and negative impact on reputation or quality of human resources by a worker constitutes desirable turnover. Undesirable turnover occurs when a firm needs a worker and values their input, teamwork, leadership skills, or unique talent and the worker leaves due to personal reasons, sickness, family, or retirement. Despite the presence of a plethora of research regarding turnover, organizations still find it hard to determine the actual cause of loss of employees to their industry competitors, joblessness, or other industries. An adequate understanding of the industry is essential in investigating the subject matter. The Saudi Arabian hospitality industry is one of the country’s fastest developing sectors. Both Jeddah and Riyadh draw more hotel brands and groups than any other destination in the region. The hotel inventory for Riyadh includes 119 properties, which have 16,411 keys. Jeddah has 92 hotels, which have 11276 rooms (Bawaba, 2018). These two cities have the potential to increase the number of hotels and the capacity of existing hotels. The primary signifiers of potential progress in the industry include the major infrastructural projects, of which Riyadh has 48 in the pipeline. The massive growth of the hospitality industry is also evident in other fields. Saudi Arabia’s construction pipeline has 60% of the 143 hotels, which opened up in 2018 (Mather & Smith, 2018). Riyadh and Jeddah rank third and fourth respectively in terms of hospitality development in the Middle East. The hospitality industry in Saudi Arabia does not show any signs of changing soon. Savills, a real estate agency, has predicted enormous growth in the hospitality industry throughout the Kingdom, for example approximately 22.1 million visitors touring Saudi Arabia by 2025 (Hotelier Middle East Staff, 2019). The report dubbed ‘Saudi Arabia Hotel Sector Report’ predicted a 13% increase in hotel rooms in 2017, and the figure came true after the construction of over 48,000 extra rooms that year. This report narrowed down the major factors fuelling tourism in Saudi Arabia. Most people come for leisure, corporate reasons, and pilgrimage. Tourism and travel account for 9.4% of Saudi Arabia’s GDP, while the expenditure of travellers has grown annually by 10.5& (Alodadi & Benhin, 2015). The country’s Vision 2030 vision focuses on the diversification of the economy and predicted a 4% annual increase in foreign visitor arrivals. A diversified economy for Saudi Arabia is predicted to cause an increase in employment opportunities and growth in the Kingdom’s GDP. Many hotel brands are the major drivers of construction activities in the country, and they are keener than ever to meet the nation’s demands from local and international tourists. This trend is likely to continue through to 2025 when the tourist numbers reach an expected 22.1 million and 2030, by when the country requires a certain level of GDP growth and new employment opportunities. Several initiatives put forward to meet the country’s 2030 goals require massive recruitment of personnel to ensure that the $64 billion invested in culture, entertainment, and leisure reward investors adequately. Some of the outstanding projects in the hospitality industry include the Red Sea Development project backed by the Public Investment Fund and the Amala megaproject. Amala is set for completion in 2028 while the Red Sea Development project will be ready by 2022 (Khan, 2016). The need for human resources in the country is intriguing. For example, the government and private sector continually invest in religious and cultural events. Hajj and Umrah visitors could reach 30 million by 2030 (Hotelier Middle East Staff, 2019). The country also considers visa extensions of 30 days for such visitors to increase the level of activity in the hotel industry. Currently, the annual increment in visitor length of stay record stands at 9.7 to 11.3 days (Alodadi & Benhin, 2015). The country is also expected to experience a surge in corporate travel demand, with growth in other industries such as oil. Business travellers pushed the 2018 expenditure from visitors to 52.5% for corporate travellers alone in Riyadh (Hotelier Middle East Staff 2019). This wave of massive expansion requires consistency in the human resource factor for the country’s hospitality industry. Statement of the research problemDue to the ‘hidden’ nature of costs associated with employee turnover, many organizations in the hotel industry tend to underestimate the severity of the issue (Karsan, 2007). Although direct costs resulting from employee turnover can be easily quantified, indirect costs arising from the culture are significantly more difficult to quantify (Karsan, 2007). O’Connell and Kung (2007) state that although organizations tend to underestimate the cost of turnover, collectively it amounts to billions of dollars annually. The average cost of replacing an employee, according to the Bureau Labour Statistics in America, is $13,966. From an investor’s perspective, it is essential to understand the reasons behind employee turnover in the hospitality industry, since it is a source of leakage. Additionally, employees in the industry need to become acquainted with the reasons behind personnel turnover in the industry if they are to lobby/champion for positive change. This research focussed on understanding the reasons behind employee turnover in Saudi Arabia’s hospitality industry. Objective of the studyThe research’s aim was to assess the following objectives:1. The impact of individual factors on employee turnover in Saudi Arabia’s hospitality industry.2. The impact of organizational factors on employee turnover in Saudi Arabia’s hospitality industry.3. The impact of job-related factors on employee turnover in Saudi Arabia’s hospitality industry.Research questionsSpecifically the research sort to address the following:1. Whether organizational factors influence personnel turnover in Saudi Arabia’s hospitality industry.2. Whether individual factors influence personnel turnover in Saudi Arabia’s hospitality industry. 3. Whether job-related factors influence personnel turnover in Saudi Arabia’s hospitality industry.FeasibilityThe research relied on both primary and secondary data. Primary data was collected quantitatively via questionnaires. Secondary data was obtained from already available material on the subject, such as surveys on the topic conducted by other credible individuals or organizations. The researcher relied on his connections in the country’s hospitality industry to seek approvals and necessary permissions needed for the purposes of data collection. Justification of the topicOne of the challenges facing the hospitality industry is the high levels of employee turnover. According to the National Restaurant Association (2017), the figure topped 70% in 2016. This study is of particular interest to stakeholders in the hospitality industry, especially organizations in the sector that aim to regulate their rates of employee turnover. This study’s findings will enable decision makers in the hospitality industry to make informed decisions regarding the overall welfare of employees. Scope of the studyThe study explored organizational factors that influence employee satisfaction. These issues included payment rates that fall below industrial standards. In an age of free information flow, employees’ awareness increases gradually after entering any industry, hospitality included. Another pay-related issue addressed was “cutting” employee remuneration. Most firms aim to improve perks for workers, but a change in profitability of the entire industry can influence their remuneration policies. This study showed the importance of declaring various clauses before engaging the services of employees to ascertain their stay, avoid a high turnover ratio, and control attrition. The research also addressed the struggle to balance employee retention and business health. Other regulatory issues discussed in the study include the recognition of employee efforts and availability of growth opportunities in the hospitality sector. Employees’ issues constituted the bulk of the literature and investigations conducted in the study. Personal matters investigated included work-life balance, personal expectations, feeling undervalued, lack of feedback and coaching, and employee misalignment. The study also addressed problems in supervision where employees lacked decision-making abilities due to managers’ micromanaging even minute tasks. The study also focused on job-related factors such as job stress, job stressors, job dissatisfaction, and lack of organizational commitment. Significance of the studyThis study is beneficial to firms in the hospitality industry attempting to increase their productivity by addressing the rate of employee turnover. The human resource management policies suggested in this study ensure that employers retain employees who understand their organization’s goals and strategies and those who are crucial to achieving organizational ambitions. Adopting the solutions and recommendations of this study will ensure that businesses in the hospitality industry maintain their profitability through better approaches to employee turnover. Most organizations suffer from gratuity and litigation costs when disgruntled employees institute legal disputes with the firm as they leave. This study also addressed separation policies in Saudi Arablia’s hospitality industry to guide employers in avoiding litigation. Definition of termsEmployee turnover is a term in the human resources context referring to the replacement of one worker with another. The reasons for the parting could be death, interagency transfers, resignation, retirement, and termination. Hospitality is the relationship between a host and a guest. The hospitality industry capitalizes upon this relationship, banking on the host’s ability to exercise goodwill through entertainment and reception to strangers, visitors, and guests. Limitation of the studyThe study contains broadly formulated research aims and objectives including the exploration of job-related, personal, and organizational causes for employee turnover. This broad definition has limited the extent to which the researcher addressed individual factors. The study was also challenged by lack of information on the high rate of employee turnover for the hospitality sector in Saudi Arabia. The study limited the scope of discussion to the hospitality industry alone and chose to address Saudi Arabia specifically, despite the extensive nature of the hotel and tourism sector in the Middle East.

2. Literature Review

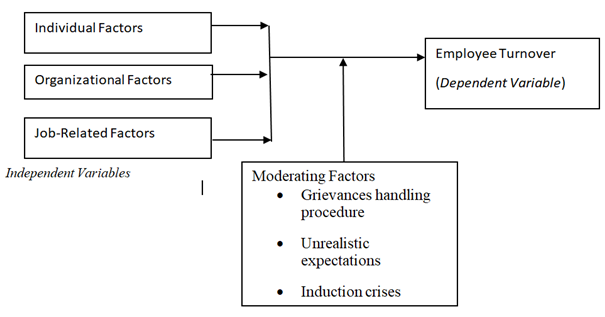

- Employee TurnoverAccording to Price’s (1977) study, the phrase “turnover” is described as the ratio of employees who leave the organization divided by the average number of employees during the period being considered; every time a position falls vacant, a new employee has to be hired and trained. Labor turnover refers to the employees’ movement in and of a given business (Abassi & Hollman 2005). This turnover affects firms and workers; employees may have to learn new, job-specific skills, whereas firms continuously incur hiring and training costs for new workers (Agrusa & Lema 2007). These new employees might be extremely motivated and skilled. Thus, turnover might improve the performance of the firm. Nonetheless, high labor turnover triggers challenges for the organization since it is expensive, and also reduces overall morale and productivity (Price 1977). Labor turnover can be sub-divided further into two major kinds: involuntary and voluntary. The latter type is where the workers leave of their own free-will, whereas the former one is because the employer has decided that employment needs to be terminated (Abassi & Hollman 2005). Employee retirement can fall under either of the two types. Usually, voluntary turnover emerges when certain workers leave to escape adverse work environmental factors while other employees are pulled away from the firm by more appealing opportunities (Armstrong, 2012). Employees will quit for various reasons, however, a great percentage of such reasons are never associated with management (Atwal & Williams 2012). Recent studies have shown that involuntary turnover applies to employees with poor performance or those who have made severe mistakes that prompted the firm to encourage them to leave, as opposed to being fired by the organization (Abassi & Hollman 2005). The Hospitality Industry Turnover Culture:In their article “Turnover Culture in the Hospitality Industry”, Iverson and Deery (1997), indicated that with a sample of 246 employees from six five-star hotels in Australia, they found that turnover culture was the leading cause of employee intent to exit an organization followed by other variables such as negative affectivity, union loyalty, and organizational commitment. The authors recommended implementing HR strategies with wider implications on the management of turnover in organizations (Iverson & Deery, 2007). In assessing the impact of culture on organizations, Ogbonna and Harris (2002) also mentioned that turnover culture, if not addressed early enough, could result in organizations’ losing employees in short intervals that can be as minimal as one year from the point of recruitment to the point of employee exit. It is known that the hospitality industry is extremely labor-intensive, however, the high labor turnover remains a severe challenge within the industry all around the globe. According to Mobley (1977), an array of factors like pay, social integration, communication, reutilization, promotional opportunities, role overload, training, co-worker and supervisor support, and distributive justice have been identified as having substantial influence on turnover. The main reason for operational and managerial turnover is voluntary resignation, preceded by internal transfers (Clarkson, Van Bueren & Walker 2006). Performance associated terminations stood extremely low (Elding, Tobias, & Walker 2006). The major motivating factors for managerial, supervisory, and executive staff to alter jobs, within the hospitality industry, were better career opportunities alongside better working hours (Dysvik & Kuvaas 2008). Moving to a job outside the industry was attributed to higher salaries, better career opportunities, and better working hours (Mobley, 1977). The data indicated that higher wages together with better working hours are the primary drivers for managerial workers to quit (Davidson, Timo, & Wang 2010). Similarly operational staff seek better wages, working hours and enhanced career opportunities (Davidson, Timo, & Wang 2010). Although in the past a small number of staff in the hospitality industry would stay for more than five years in their place of employment, voluntary turnover is slowly rising (Mobley, 1977). According to Mobley (1977), turnover in the hospitality industry peaks during the first four weeks of employment. Poor HR decisions and not meeting newcomers’ expectations remained the major causes of such turnovers (Mobley 1977). The high rates of employee turnover may remain endemic in the hospitality sector according to a study by Walker in 2006. The author believed that turnover rates could not be avoided (Walker, 2006). The most vital time for turnover is the initial few days or weeks of hiring a new worker in an organization (Hammerberg, 2002). Walker (2006) held that more individuals quit during this period compared to any other period and he referred to this period as the induction crisis, which takes place when the new worker has not been integrated fully into the organization for one reason or another. Failure to integrate can be due to ineffective recruitment or an ineffective induction program, with inadequate care, as well as time spent allowing the new recruit to effectively build a solid relationship with his/her co-workers and supervisors (Iverson & Deery 1997). Walker (2006) held that opportunities are huge in the hospitality industry, both locally and globally, allowing individuals with ambition to always look for opportunities to enhance their respective career prospects. Where the levels of pay do not match well with the competition, the employees’ urge to quit and earn more can become overwhelming (Jackofsky, 1984). Nonetheless, there are cases where employees stay in jobs they like despite availability of higher pay elsewhere (Kuria, Alice, & Wanderi, 2012). Studies on employee turnover in the service industry indicated that the hospitality industry leads in terms of the number of personnel who change occupations frequently. Stalcup and Pearson (2001) found that poor pay and irregular payments were the major causes of employee turnover in Bangladesh’s hospitality industry. Out of the respondents contacted by the researchers, 45% indicated that the poor compensation packages and irregular modes of payment were the reasons behind their exit from organizations in the industry (Stalcup & Pearson, 2001). 10% of the respondents indicated that their reason for leaving included the availability of better and more suitable job options (Stalcup & Pearson, 2001). When asked to suggest solutions for high employee turnover in the industry, 80% of the respondents proposed a standardized salary structure, while 70% suggested regular salary increases (Stalcup & Pearson, 2001). Walker (2006) echoed Stalcup and Pearson’s (2001) findings by stating that in cases where pay levels did not compare well with the competition, employees’ urge to leave an organization was “overpowering”. According to Walker (2006), employees may reconsider their decision to exit a firm offering low wages if the employment conditions, such as career advancement opportunities, are favorable. The studies indicate that salaries (pay package) significantly influence whether an employee quits or stays in an organization in the hospitality industry.Factors influencing employee intent to quit in the Hospitality IndustrySeveral factors affect employee turnover. Employees often exit their jobs due to inadequate wages (Mobley, 1977). Nonetheless, various studies demonstrate that apart from wages and salaries, several complex factors affect employee turnover, for instance management styles and various psychological factors (National Restaurant Association 2017). Factors that influence employee turnover are highlighted in the subsequent sections.Work Associated Factors:Work related factors that influence turnover in the hospitality industry include job satisfaction, working environment, pay, work performance, organization commitment, and promotion opportunities (O’Connell & Kung 2007). Job PayKuria, Ondingi, and Wanderi (2012) carried out a study to establish the causes of labor turnover in Kenya’s three and five star hotels. The researchers found that poor remuneration was the major contributor to staff turnover with 60% of the respondents citing that they were not satisfied with their salaries. These findings reinforced the conclusions reached by Stalcup and Pearson (2001) and Walker et al. (2006) on the significance of remuneration on employees’ decision to exit or stay in a given organization. According to Kuria et al.’s (2012) study, 56% of the respondents stated that the lack of involvement in decision making and creativity was the reason behind their dissatisfaction with their current employee, and as such, reason enough to quit. The lack of a defined reward scheme (motivation criterion) was also cited by 46% of the respondents as a reason behind their decision to either quit or stay in their current organization (Kuria et al., 2012). The researchers also found that employee turnover was higher in three star hotels (68%) than in five star hotels (13%).Available literature shows that the average yearly wage in the hospitality industry stays low compared to wages in other industries like Information Technology or Education (Stalcup & Pearson, 2001). A low starting salary is evident in frontline departments in the hospitality industry, such as food and beverage, housekeeping, and front office (Price, 1977). It has been demonstrated that dissatisfaction with pay remains amongst the key factors influencing turnover. Staff and managers receive their pay in terms of salary, wages, and fringe benefits, which they expect to be commensurate to the efforts and services they provide in the organization (Kuria et al., 2012). Hence, if there is a surge in pay, it can lead to a decrease in labor turnover (Ramlall, 2004). The relationship between job satisfaction and pay has received a significant attention. Pay is the most significant factor that contributes to job satisfaction in the hospitality industry. Thus, high pay is significantly linked to greater job satisfaction. Employees are more likely to be satisfied with their respective jobs when pay received is more than the anticipated pay (Stalcup & Pearson 2001). Job SatisfactionJob satisfaction encompasses salaries/wages; the work itself; supervision, and promotion opportunities. Job satisfaction can be defined as the happiness or unhappiness of workers as they discharge their responsibilities (Swerlow & Roehl, 2003) and as the positive emotional reaction of a person to a specific job (Taylor & Medina, 2013). The phrase “job satisfaction” is regarded as an attribute existing as the equity of the range of desired as well as non-desired job-associated experiences (Clarkson et al., 2006). It is further described as the degree of fit between job features and employees’ anticipation. Job satisfaction is a product of both the aspirations and expectations of employees and their current status (Stalcup & Pearson, 2001). Workers who are not satisfied with their jobs are more likely to exit an organization than their satisfied counterparts (Taylor & Medina, 2013). Where employees have high levels of job satisfaction, the firm will experience decreased rates of labor turnover (Clarkson et al., 2006). The Work Itself The nature of the work itself is a vital dimension in the job satisfaction of employees. The internal satisfactory variables linked to work include feelings of accomplishment, feelings of independence, self-esteem, and control (Stalcup & Pearson, 2001). External satisfactory variables include praise from a boss, good relationship with peers, good working environment, good utilities and welfare, as well as high salary (Swerlow & Roehl, 2003). No association between stress and job satisfaction was highlighted in the literature reviewed (Stalcup & Pearson, 2001). It is argued that high levels of work stress will reduce job satisfaction and ultimately force employees to leave as they feel their duties are too challenging to accomplish (Stalcup & Pearson, 2001). Job stress can be categorized into four key types including lack of resources for performance, workload, clarity of a worker’s role, and role conflict (Stalcup & Pearson, 2001). Increased job stress is associated with increased intent to leave the firm. SupervisionWhen investigating the issue of employee retention in organizations, Agrusa and Lema (2007) discovered that more people exit organizations because they do not get along with their superiors than for any other reason. According to the authors, customer and employee turnover are directly linked, especially within the service industry. Therefore, for the purposes of maintaining healthy revenue margins, organizations in the hospitality industry should enact measures aimed at reducing employee turnover (Argusa & Lema, 2007). Nadiri and Tanova (2010) echoed Agrusa and Lema’s (2007) findings, stating that fairness of personal outcomes received by employees had a significant impact on their turnover intentions. The author’s stated that perceived unfairness in a firm’s procedures can harm the relationship between employees and their supervisors, directly impacting turnover intentions of both parties (Nadiri & Tanova, 2010). Supervision is another factor influencing job satisfaction and is described from the employee’s perspective. Supervision is displayed in various ways including checking to observe how well the subordinate is doing, giving advice as well as support to people, and communicating with employees on both personal and official levels (Price, 1977). Some studies have shown that satisfaction with an employee’s supervisor will impact job satisfaction in a positive manner thereby decreasing employee turnover in the hospitality industry (Nadiri & Tanov, 2010). Supervisors offering increased concern and social assistance to workers lead to decreased turnover due to increased staff satisfaction (Qualtric, 2018). Promotion OpportunitiesOpportunities for promotion, whereby employees have the potential to get promoted to a higher status within the firm (Nadiri & Tanova, 2010) are helpful in determining whether an employee is dissatisfied or satisfied since these opportunities are often linked with an increase in wages and salaries (O’Connell & Kung, 2007). Nonetheless, findings have shown that the hospitality industry lacks opportunities for promotion instead of having adequate and fair promotion policies (Nadiri & Tanova, 2010). The absence of opportunities for promotion in the hospitality industry can lead to a decrease in the chances of retaining talented workers in these organisations (National Restaurant Association, 2017). When workers suffer from unfair treatment, they change their attitude on job promptly and might leave in the long run (Ogbonna and Harris 2002). The Organization’s CommitmentPennstate (2006) held that commitment by an organization to retaining its employees determined how attached an employee would feel to the organization they were working for. Organizational commitment is vital since committed workers remain less likely to quit and are more likely to have higher performance (Pennstate, 2006). Three dimensions of such an organizational commitment have been established; these include affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment (Elding et al., 2006). The existing literature has established a firm association between turnover and the organization’s commitment, which demonstrated that workers with low commitment are likely to vacate organizations (Mobley, 1977). A positive relationship, on the other hand, has been established between organizational commitment and progress in careers or internal promotions. This shows that promoted workers are more likely to showcase higher organizational commitment (Lefever, Dal, & Matthiasdottir, 2007). Work PerformanceWorkers’ performance is another variable that affects employee turnover in the Saudi hospitality industry. Jewell and Siegal (2003) showed that workers who have high performance do not wish to quit their jobs. To this end, if workers have low performance, they will quit their respective organizations for a range of reasons, and labor turnover will not be a significant issue for the organization (Swerlow & Roehl, 2003). However, where the employees have high job performance, their turnover will be of greater significance to the company. In this case, the company will always try to prevent such exit. Lower wages, prize exclusions, and unsuitable jobs are further reasons that contribute to low performance alongside high worker turnover (Kuria et al., 2012). Demographic FactorsA great proportion of voluntary turnover models encompass demographic variables like gender, age, tenure, race, number of dependents, marital status, and educational experience (Jackofsky, 1984). Nonetheless, the emphasis in this paper will be on marital status, age, and education level. Education Level In Saudi, one of the primary challenges within the hospitality industry is how to retain highly-educated workers (Hammerberg, 2002). Educated staff is defined as employees who have successfully undergone a higher education program at the Bachelor’s and Master’s level (Iverson & Deery, 1997). People who are highly-educated managers or those who are non-managers are more like to reach turnover decisions (Dysvik & Kuvaas, 2008). According to Blomme Van Rheede, & Tromp (2010), among the alumni of the Hospitality School, The Hague, who work globally, nearly 70% of graduates quit their respective organizations within six years. Highly-educated workers within the hospitality industry generally feel less satisfied with their jobs than less-educated staff, since the former have higher expectations for their job status and salaries. They might also lack the will to either join or stay in the hospitality industry (Elding et al., 2006). Moreover, external labor markets tend to provide several opportunities for highly educated workers to satisfy their high expectations for financial gains (Fox, 1997). Gender FactorsDoherty and Manfredi (2001) revealed that men and women have specific behaviors, which impact the labor turnover in an organization. According to their study, women employees quit their jobs more often than men within the hospitality industry since women’s roles involve taking care of children, having babies, and household duties (Doherty & Manfredi, 2001). Moreover, women, specifically those married, tend to spend more of their time in household activities and are significantly more prepared to vacate their respective jobs for family-linked reasons than their male counterparts. Some female workers do not wish to go back to their jobs after having a baby (Blomme et al., 2010). The literature has also shown that men tend to have higher job satisfaction with pay as compared to their female counterparts, while females tend to haveer high job satisfaction with co-workers than their male colleagues (Atwal & Williams, 2012). This implies that female employees tend to give higher ratings for social needs, such as working with individuals and being of assistance to other people, than their male peers. Men tend to regard pay as more vital than women. Women usually start their careers with lower anticipations than males and are more willing to take career risks and influence their employers (Doherty & Manfredi, 2001). Women employees work mostly at entry level jobs in the hospitality industry and hence get less pay as compared to their male colleagues (Armstrong, 2012). Iverson’s (2001) study in the United States established that women managers in the hospitality industry get much lower wages than fellow male managers whether in starting or at the top of their respective careers (Iverson, 2001). Burgess’ (2000) study similarly showed that male workers get higher salaries than women employees and suggested that to balance the disparity among male and female employees, routine and basic jobs are given to female, rather than male workers (Burgess, 2000). Marital Status Marital status also influences employee turnover. Married workers are more concerned with family-work-life balance (Agrusa & Lemam, 2007). Married employees do not desire voluntary turnover since they have several concerns regarding financial needs of their respective families. In case married workers are unable to withstand the long and unstable working hours, they can always give up their job. Nonetheless, the issues usually take place amongst women (Abassi & Hollman, 2005). Thus, married women will have increased time for family life and even successfully take care of their respective children (Atwal & Williams, 2012). Age Generation Y workers have the highest percentage of employee turnover in the hospitality industry. Moreover, younger employees have shown a higher propensity to exit than older, more mature workers. The challenge is that workers of the baby boomer generation gradually retire (Blomme et al., 2010). These baby boomers have been through the eras of war, hence, show less opportunity in education institutions. Such workers demand increased stability in their respective workplace, and are extremely loyal to their respective employers (Clarkson et al., 2006). However, Generation Y workers, born between 1979 and 1994, are unable to adapt to changes easily and search for higher life standards, hence, they consider many factors that meet their interests in their work. Generation Y workers will change their jobs to enjoy more experiences and diversify their lives (Davidson et al., 2010). External FactorsExternal variables that affect employee turnover include factors that cannot be controlled by the organization and are challenging to predict with certainty (Elding et al., 2006). These include political shifts, modified or new regulations, legislations, global economic conditions, major mining disasters, and technological changes (Dysvik & Kuvaas, 2008). The hospitality industry remains heavily impacted by global economic conditions, which might predict employee turnover within hospitality industry (Fox, 1997). The rate of unemployment can affect employees’ perceptions of job satisfaction (Hammerberg, 2002). During an economic downturn, workers with high levels of job dissatisfaction might still remain in the firm since they do not wish to lose their present job, while the job market lacks opportunities for them to get better jobs (Iverson & Deery, 1997). Nonetheless, where economic conditions have enhanced, workers are more likely to quit the organization to get a better job (Jackofsky, 1984). Thus, enhancing economic conditions may create a high labor turnover level (Karsan, 2007). In the subsequent sections, the paper focuses on the management of labor turnover in the Saudi hospitality industry in order to minimize its effects within the industry. The Labor Turnover CostIn previous sections, a considerable number of critical factors influencing labor turnover have been highlighted. The following section will emphasize the cost of employee turnover and its associated effects on the Saudi Arabia hospitality industry. Employee turnover is a substantial cost to the hospitality industry and it might be the most critical factor that affects the hospitality industry’s service quality, skill training, and profitability (Kuria et al., 2012). The labor turnover cost remains multidimensional, including low morale, low performance standards, low productivity, and increased absenteeism (Lefever et al., 2007). A study conducted by TTF Australia (2006) demonstrated that the cost of managerial employees’ replacement stood at $109,909 per hotel and the yearly cost of replacing the operational worker stood at $9591 per worker. The total yearly cost of turnover stood at 49 million dollars, which is equivalent to 19.5% of the sixty-four surveyed hotels total payroll costs of $250 million (TTF Australia, 2006). Marriot Corporation specifically was found to have estimated that every one percentage point rise in its worker turnover rate, cost the firm between five and fifteen million dollars in lost revenue. Thus, labor turnover cost is extremely high (Nadiri & Tanova, 2010). Employee turnover is not exclusively an important tangible dollar cost but also an intangible or even “sealed” cost linked to loss of efficiency, skills, and replacement costs (National Restaurant Association, 2017). The direct influence of labor turnover can trigger financial suffering, like administrative costs, alongside lost investments in training as well as lost staff expertise, which are typical examples of the cost of turnover and opportunity costs (TTF Australia, 2006). Employee turnover also has indirect impacts including lack of manpower, poorer quality service and reduced employee morale (O’Connell & Kung, 2007). Moreover, where the employee turnover shoots, the service quality might decrease as it takes time to “back fill’ the departing workers, specifically at busy hotels (Ogbonna & Harris, 2002). Labor remains an important cost and human capital leakage via unnecessary turnover, which impedes bottom line performance (Davidson et al., 2010). A great proportion of Human Resource Management (HRM) practices have been highlighted as potential solutions for employee turnover, such as investment training, providing support to the organization, embracing innovative recruitment, as well as selection procedures and processes, and providing better opportunities for careers alongside adopting the right measures to boost employee commitment and job satisfaction (TTF Australia, 2006) Managing Employee Turnover in the Hospitality IndustryHigh turnover of employees remains a common challenge in the hospitality industry, and it is a primary factor that affects the efficiency of workplace productivity as well as hotel cost-structure (Price, 1977). Labor turnover denotes a problem for modern HRM practices and strategies (Qualtrics, 2018). Thus, in this part of the review, the paper focuses on how to effectively manage employee turnover from the perspective of HR. Labor turnover cost was highlighted in the previous section. The total annual cost of employee turnover stood at about forty-nine million dollars, equivalent to 19.5% of the sixty-four studied hotel payroll costs, that stood at 250 million dollars (TFF Australia, 2010). The cost of employee turnover is extremely high, therefore, awareness of the significance of employees staying with a firm is a reality (Ramlall, 2004). Hinkin and Tracey conducted a study in 2000 that showed that hospitality executives with a clear understanding of human capital value and adopting organization policies together with management practices in search of worker retention will override their competition. Organizations with effectively designed alongside well-implemented retention programs for workers, which increase the tenure of worker, always pay for themselves via decreased cost of turnover and enhanced productivity (Hinkin & Tracey, 2000). The study Baum conducted in 2006 on 2500 supervisors, executives, and managers within the hospitality industry showed the top five most significant aspects that will help an organization retain their employees. These factors included effective communication, efficient leadership, better career paths, desired development, and deeper understanding of aspirations, as well as assisting employees towards accomplishing these aspects (Baum, 2006). This implies that workers use these five aspects as determinants of their job satisfaction (Stalcup & Pearson, 2001). Thus, when HRM effectively designs a scheme for retaining workers, they should always consider those five aspects before making any decisions (Baum, 2006). Employee MotivationMotivating staff remains as critical to success as any personal attributes or skills and it further plays a central role in staff retention (Swerlo & Roehl 2003). Motivation describes the process through which the efforts of an employee become energized, directed and sustained towards goal achievement (Dysvik & Kuvaas, 2008.). Motivating staff remains a core aspect in staff retention, and assists in boosting job satisfaction, hence will lead to a decline in the rate of labor turnover (Stalcup & Pearson, 2001). It remains vital for the hospitality industry management to establish efficient HRM practices and policies that allow them to effectively motivate competent workers contributing to the achievement of their objectives (Ramlall, 2004). This calls for workers at various management levels and career stages to maintain high and desirable morale alongside high performance (Stalcup & Pearson, 2001). Satisfied workers will assist hotels in improving customer satisfaction in the long-run and contribute to retaining a huge loyal customer base (Taylor & Medina, 2013). In his study “Reasons for Employee Turnover in a Full Priced Department Store” Hammerberg (2002) found that 67.7% of the store’s employees had served for a period of less than a year. The researcher noted a very high rate of attrition in the department store, which created doubts about the store’s recruitment procedures. The researcher also found that 16% of the respondents (the store’s employees) had served for a period of between one to two years. According to Hammerberg (2002), job-related factors were the main cause for employee turnover, accounting for 37.4% of all cases of employee turnover within the organization. Individual factors accounted for 30.3% of the store’s employee turnover cases (Hammerberg, 2002). The author held that reasons for exiting the store were the same for both part-time and permanent staff. The research indicated job-related and individual factors as being some of the reasons behind employee turnover.TrainingAccording to a study by Atwal and Williams (2012), when an organization offerred appropriate employee training for assuming greater responsibilities, rates of turnover significantly decreased. Various studies have shown that proper employee training is related to retention and productivity. Staff retention is important for every organization’s success and hence various hotels annually invest huge amounts of money to effectively develop their staff (Mobley, 1977). These firms have realized that providing employee training can improve their productivity and enhance their job performance. Thus, organizations should offer training, which will reduce the labor turnover problem in the long-run within the hospitality industry. Also, the hospitality industry is currently has a shortage of middle management workers (National Restaurant Association, 2017). Thus, training programs are essential to train and develop new management personnel. In 2004, for instance, Shangri-La Hotel & Resorts’ Shangri-La Academy was established as a full-time facility handling internal training to help employees progress up the desired ranks (Nadiri & Tanova, 2010). Moreover, the Intercontinental Hotel Group launched its in-house training centre for grooming high-potential workers to assume managerial positions within the organization. Such measures aim at increasing retention rates of workers as well as addressing the pattern of experienced staff shortage and minimizing employee turnover (Atwal & Williams, 2012). Theoretical frameworkHigh turnover levels are costly to any organization, both directly and indirectly. The reasons behind employees’ desire to leave an organization are usually tied to the level of satisfaction enjoyed by the employee (Armstrong, 2012). The “ push” factors that cause employees’ dissatisfaction include compensation packages, work environment, inconsistent HR policies, low employee benefits, lack of challenges, incorrect work assignment for level of competence, lack of career advancement schemes, and fear of being found out if the employee falsified his/her qualifications (Lefever et al., 2007). On the other hand “pull” factors include higher compensation packages and greater technical challenges (Kuria et al., 2012). The study focuses on the sources of employee turnover in Saudi Arabia, which have been classified into three broad categories; individual, organizational, and job-related factors (Karsan, 2007). Conceptual Framework

Summary and ConclusionsEmployee turnover has been defined in this paper as employees’ movement in and out of a business. Employee turnover may improve organizational performance, however, extremely high turnover triggers problems for the organization since it reduces morale and productivity. Employee turnover can be sub-divided into two primary types: voluntary and involuntary (Hammerbergm 2002). High employee turnover is a major challenge to the hospitality industry in Saudi Arabia. An array of other factors including communication, pay, reutilization, social integration, work/role overload, training, promotion opportunities, co-worker and supervisor assistance, alongside distributive justice have significant influence on employee turnover (Fox, 1997). The labor turnover rationale in the hospitality industry is categorized as work linked factors, demographic, as well as external factors (Jackofsky, 1984). Work-associated factors define job satisfaction as the unpleasantness or pleasantness of the work for an employee within an organization (Elding et al., 2006). It entails employee satisfaction with the work itself, pay, supervision, and promotion opportunities. A satisfied employee is more likely to stay in the job resulting in lower employee turnover within the organization (Iverson & Deery, 1997).

Summary and ConclusionsEmployee turnover has been defined in this paper as employees’ movement in and out of a business. Employee turnover may improve organizational performance, however, extremely high turnover triggers problems for the organization since it reduces morale and productivity. Employee turnover can be sub-divided into two primary types: voluntary and involuntary (Hammerbergm 2002). High employee turnover is a major challenge to the hospitality industry in Saudi Arabia. An array of other factors including communication, pay, reutilization, social integration, work/role overload, training, promotion opportunities, co-worker and supervisor assistance, alongside distributive justice have significant influence on employee turnover (Fox, 1997). The labor turnover rationale in the hospitality industry is categorized as work linked factors, demographic, as well as external factors (Jackofsky, 1984). Work-associated factors define job satisfaction as the unpleasantness or pleasantness of the work for an employee within an organization (Elding et al., 2006). It entails employee satisfaction with the work itself, pay, supervision, and promotion opportunities. A satisfied employee is more likely to stay in the job resulting in lower employee turnover within the organization (Iverson & Deery, 1997).3. Research Methodology

- Research approachThe study relied on quantitative methods. These research methods depend on the positivist approach adopted by the researcher. Positivism relies on facts acquired through observation and measurement (Tüzemen, 2016). The method involves delegating the collection and objective interpretation roles to the researcher. Most studies using a positivist approach adopt a deductive approach. Deductive approaches to research involve obtaining a hypothesis that depends on existing theories and using an appropriate strategy for testing. Deductive inference relies on the truthful nature of the premises to make an accurate conclusion in the study. The study will begin from a general point to a specific one instead of generalizing from the relation between the specific and the general, as seen in a deductive research approach. Deductive reasoning guides the method of data collection that will use the information collected to evaluate the hypothesis or proposition about an existing theory (Novins et al., 2018). In the end, the researcher attempts to show the verification or falsification of the argument. Primary data collectionThe researcher relied on questionnaires to collect primary data for the research. Questionnaire designThe design process began with the identification of the goals, aims, and questions that the researcher felt were adequate to cover all relevant aspects of the study’s phenomenon (Shewhart, 2009). The process involved the definition of the main concepts, including turnover rate, the hospitality industry, the Saudi Arabian context, and human resource management in such a trade. The next phase involved selecting a survey mode which could be the telephone, the internet, or face-to-face. After the mode selection, the researcher designed the questions and constructed an individual query to reflect all factors considered before. The questionnaires were then administered to collect the data for the research. After data collection, the researcher summarized and analyzed the information. The final phase of the questionnaire design involved the formulation of different conclusions and communicating the results of the study. Research population and sampleThe initial sample for the study constituted 270 participants from different organizations. This figure was a product of the Qualtrics Online Sample size calculator, an online tool that aids in the determination of the ideal sample size (Qualtrics, 2019). The sample size was arrived at using a 95 percent confidence level and a 5 percent margin of error. Survey administrationThe study employed the use of self-administered questionnaire that did not require supervision or guidance. Data analysisThe study relied on inferential statistical methods to analyze the data. The specific technique of choice was multiple regression analysis, which is useful when interpreting the relation between two or more variables. Reliability and validityReliability is the consistency of a particular measure. The study achieved all measures of reliability including test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and inter-rater reliability. Research ethicsThe researcher observed all ethical rules that guide responsible conduct in the course of the study. The researcher maintained objectivity at all times during the research process.

4. Research Findings and Discussion

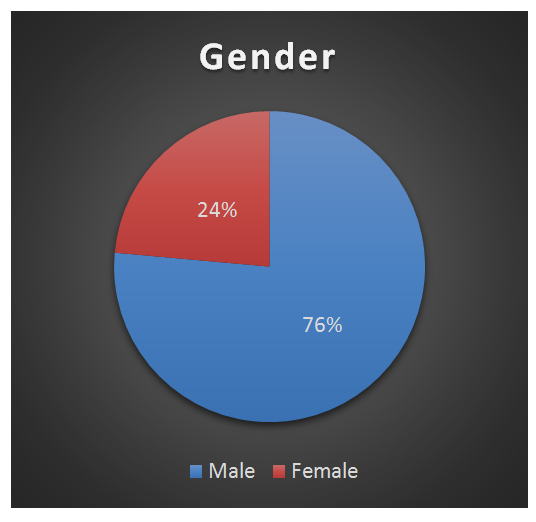

- Demographic InformationGender24% of the respondents were female while 76% were male. Saudi Arabia struggles with gender imbalances that affect almost every aspect of life. This sample is an excellent example of gendered representation, which arises from a study like most samples in this section of the Middle East population. The graph below represents the percentage of male and female participants.

| Figure 1. Gender |

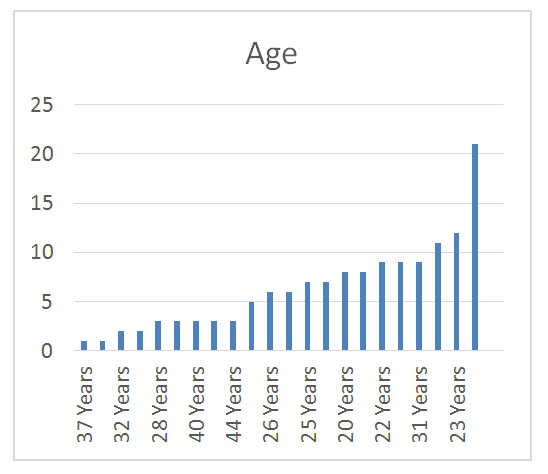

| Figure 2. Age |

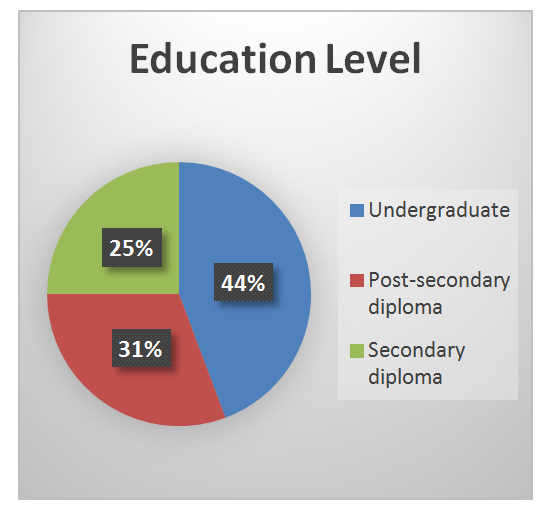

| Figure 3. Education Level |

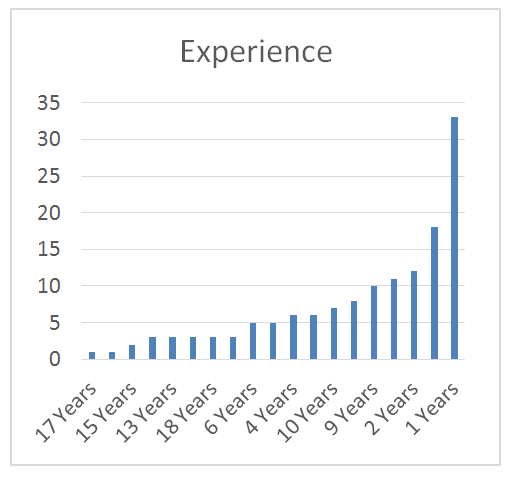

| Figure 4. Experience |

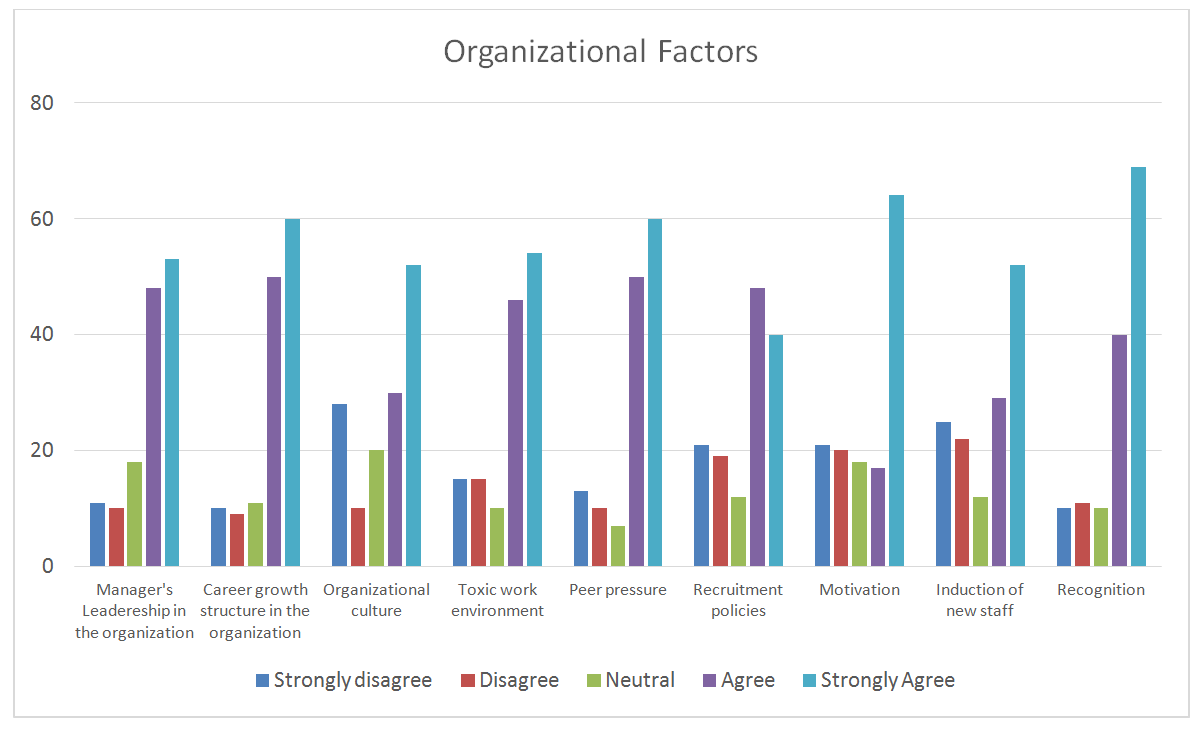

| Figure 5. Organizational factors |

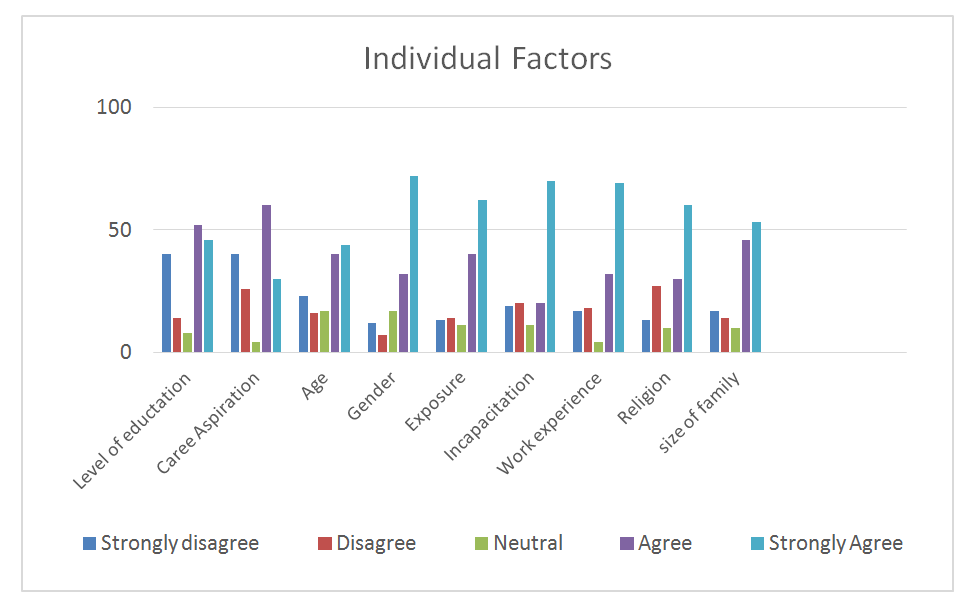

| Figure 6. Individual Factors |

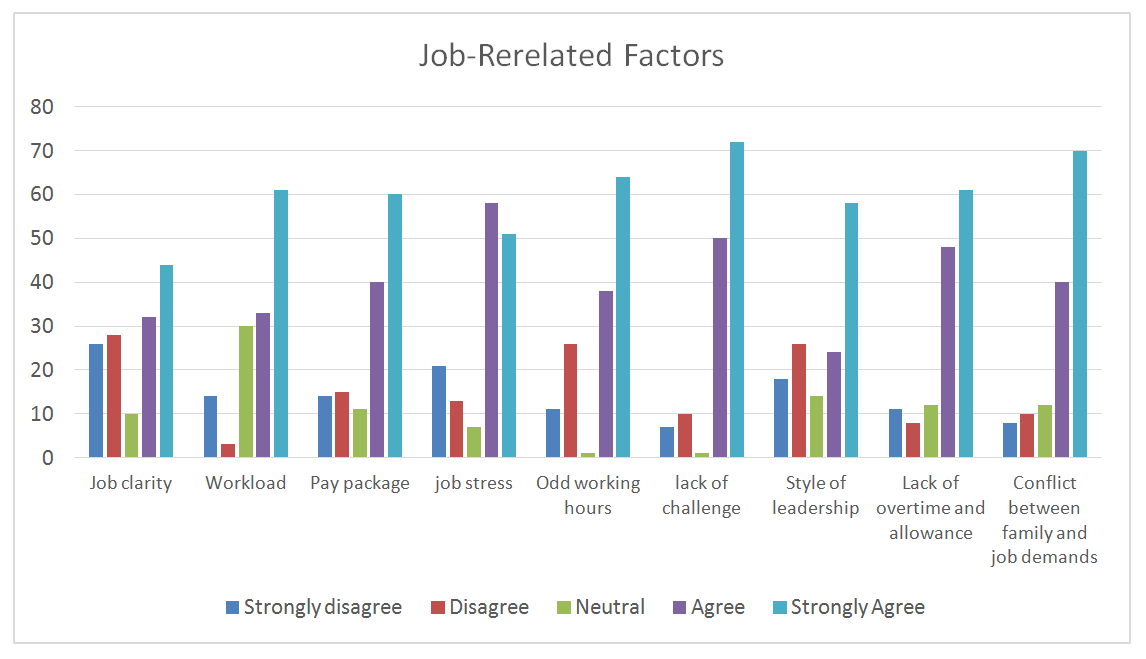

| Figure 7. Job-related factors |

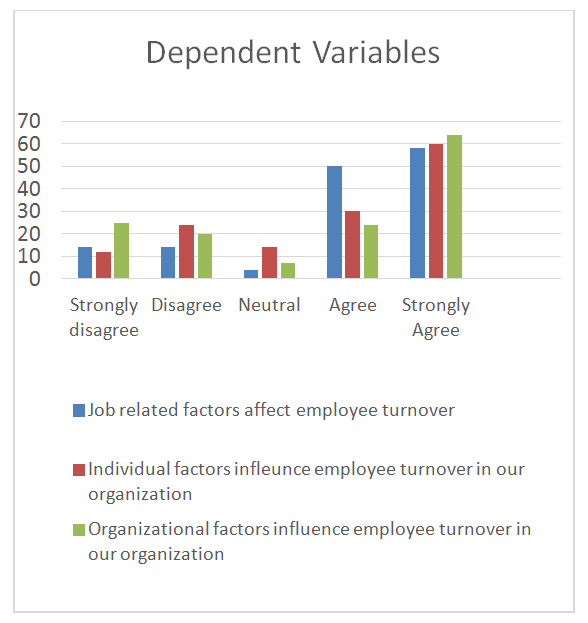

| Figure 8. Dependent Variables |

5. Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations

- ConclusionA lot of the workers are young, which indicates their willingness to join the hospitality industry at a young age. However, there are fewer people above the age of 30 willing to continue working in the hospitality industry. Male workers dominate the industry but the rate of employee turnover seems to be an age-related issue. Additionally, managerial style of leadership seems to have a major influence on the career growth and job security of workers. Workers are willing to attain high level positions in the industry. Therefore, most workers are concerned about the organizational culture and the career growth structure. Hotels maintain clean workplaces that have minimal hazards and other factors, which can contribute to toxic environments. Therefore, most workers do not pay much attention to toxic work environment as a determinant of their career decisions. Peer pressure plays a key role in the choices made by workers. Despite the fact that most workers are mature, career choices made by colleagues may influence some to follow the same trends. Employees in this industry are constantly in search of new opportunities and hence, recruitment policies play a major part in making career choices. Motivation is an essential requirement for most employees. Employees require motivation so that they remain satisfied with their current positions. The difference in career aspirations among employees depends on the level of education and position held in the organization. The level of work experience determines the ability of an employee to contribute to an organization’s goals and is an essential determinant of hiring and firing decisions. Workers with a lot of experience expect promotions when opportunities arise. Incapacitation only affects workers whose roles require the use of various bodily attributes they have lost. Employees also require clearly defined duties and the workload should meet the standards agreed upon at the time the organization hired a person. The type of remuneration should align with the tasks allocated and the person’s output. Job stress and odd working hours also cause problems for workers and eventually lead to high rates of employee turnover. RecommendationsThis study sought to explore the factors that influence the rate of employee turnover in the Saudi Arabian hospitality industry. The conclusions lead to the development of several recommendations. At the Organizational LevelManagers should use leadership methods that have a positive impact on the morale of employees. Hotel managers should also develop structures such as workshops and training that help employees to grow their careers. Hotels should also develop and uphold a culture that appreciates its employees for their efforts through remuneration and promotions. The hotel management should develop methods of employee retention to minimize the impacts of peer pressure. This industry should also create mechanisms that ensure workers remain motivated. These motivational methods could include offering incentives and recognizing the performances of workers. The Individual LevelHotel management does not influence many of the individual factors but it is advisable to assign tasks and ranks based on education levels and experience. Employees should also receive promotions depending on their competence and motivation to pursue hospitality as a career. Firms in the hospitality industry should also develop methods of helping incapacitated workers to continue serving the organization. Hotels should develop a work environment that is friendly for wheel-chair users, asthmatic workers, and people with sight problems. The Job LevelManagers should clearly define tasks and the expected outcomes in the contract. Employees should receive the right amount of workload to avoid stress and imbalances between family and work life. Employers should also provide compensation that suits the type of tasks assigned. Overtime performance, for example, should be different and better than normal pay. Management should also strive to maintain a conducive work environment. Recommendations for Further ResearchFuture researcher should examine an individual organization and explore the issues leading to termination of employment for workers within a certain period. Any investigation in the future should consider using a comprehensive tool of data collection that addresses issues such as changes in organizational strategies, support systems for employees, and inconsistencies in career expectations. These factors would provide a broader look into the issue than the one provided by this study. Recommendations for Policy and PracticeThe government and labor organizations should strive to close gaps witnessed in the industry regarding gender balance. Practical and Theoretical ContributionsThis study is applicable in the hospitality industry to reduce costs resulting from the high rate of employee turnover. Companies invest a lot of money in employees through training, licensing, and education. After hiring replacements, a company repeats the same trend of training, educating, and licensing new workers. Additionally, hotels spend a lot of money on drug tests, moving expenses, and cost of advertising the new vacancy. The recommendations put forward by this study address the root cause of the problems leading to the high rate of employee turnover. Therefore, businesses in the hospitality industry have access to knowledge regarding methods of reducing such costs. Businesses in the hospitality industry could also use this study to reduce time wastage. One of the highest costs of employee turnover is time wasted in conducting exit interviews, advertising the new job, interviewing applicants, and training recruits. Supervisors generally have to fill the vacated position until the organization hires new workers. A lot of business activities could slow down due to the absence of workers lost through some of the factors addressed in this study. New workers may take a long time to learn about the new position and its requirements. Businesses that take heed of the recommendations of this study stand a chance of minimizing the time lost through the loss of employees. Team dynamics are an essential part of any human resource manager’s strategies. Frequent changes of staff leave employees who stay behind without proper team dynamics. Certain groups in the organization learn to work together harmoniously as a team but the high rate of employee turnover ends such cooperation. Personalities and work ethics of new workers could vary from those of the old one, therefore the high rate of employee turnover could have an adverse effect on the morale of workers. This study can aid in the reduction of the high rate of employee turnover and, therefore prevent the distraction of unbalanced team dynamics.This study aids in minimizing the adverse effects of employee turnover on organizational productivity. High turnover causes low productivity due to the long period taken by new employees to adjust to their new settings. New workers often lack the capacity to provide the same quality and quantity output as their predecessors. Some group projects, which rely on the cooperation of team members, may slow down and adversely affect the productivity of experienced workers in the firm. The study also prevents decreased morale caused by the resignation of a fellow worker. Employee turnover may cause discontinuity in provision of services to clients. Some of the crucial aspects of the hospitality industry require close relationships with clients. This study advises businesses on methods of preventing employee turnover and the protection of these relations. Workers who create strong relationships with clients increase customer loyalty to the business. When these workers depart the organization, they may take their clients with them or leave them without engagement; competitors then take advantage of this and recruit such clients. Therefore, this study ensures that businesses maintain continuity in service provision to their clients. This study affirms the Management by Objective theory that encourages organizations to include employees in making certain important decisions. The discussion regarding working hours, employee stress, remuneration, and risky work environment reveals these factors as major contributors to employee turnover. The Management by Objective theory dictates that such decisions require the input of workers. Managers should avoid dictating instructions, goals, and quotas and instead ask employees to participate in making decisions that touch on their daily routines. Organizations that do not use this theory could lose bright, self-motivated workers. Some employees may not care about being included in setting work-related goals, however innovative and self-motivated workers are likely to leave any job that does not offer opportunities for strategic input.This study also explored the contributors addressed in the Theory X and Theory Y that elaborates two ends of the spectrum of motivation. According to Theory X, employees are averse to work and require external sources of motivation. Many of these factors are at the personal and organizational level. For example, the balance between work and family life is an influencing factor, which this study adequately addressed. According to Theory Y, employees’ motivation could occur at the workplace. This internal motivation occurs through matching tasks to workers’ appropriate skill level, proper remuneration, and provision of safe work environments. This study addressed factors that occur in the definition of the aforementioned theory. The use of one theory over another depends on the nature of the organization and the industry. Preference for different factors in the hospitality industry, for example, shows the right theory to apply.The observations made in this study regarding career growth reinforce the Hierarchy of Needs theory. An employee must meet every goal in their hierarchy of needs before truly committing to the goals of the workplace. Employers who fail to meet any of the needs stated under this theory compel the workers to fulfill them on their own by searching for new employers. Complete employee satisfaction requires that employers address all needs, including those in the workers’ personal lives. This study also makes valuable contributions to the Expectancy Theory, which equates effort expended with an expected reward. Some of the most successful payment structures, such as the commission compensation method, use this theory. Employees can earn as much as they want since remuneration depends on their level of performance. Similarly, this study shows that organizations that provide job promotions and salary raises encourage hard work and retention of employees. Limitations and Suggested Future StudiesThis study’s scope of discussion is limited to a few issues, unlike the work of experienced scholars in the field of human resource management and the hospitality industry. The sample size was sufficient but the use of a larger sample would generate results that are more accurate. Additionally, the lack of experience in the administration of data collection methods could have resulted in flawed results. The study took place within a short time frame and with a constrained budget. Future studies on the subject should address the limitations mentioned above. They should use a large sample and increase the budget so that the data is accurate and informative. Results from Saudi Arabia’s hospitality industry also require comparison with other countries. For example, a control study done in non-Muslim nations, such as the United States, could reveal the role of religion and culture in employee turnover in the hospitality industry.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML