-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Tourism Management

p-ISSN: 2326-0637 e-ISSN: 2326-0645

2018; 7(1): 10-18

doi:10.5923/j.tourism.20180701.02

The Relationship between Terrorist Events, Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) and Tourism Demand: Evidence from Pakistan

Mir Alam, Ye Mingque

School of Economics, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China

Correspondence to: Mir Alam, School of Economics, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The aim of this study is to examine the impact of terrorism, on both the inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI) and on inbound tourism in Pakistan (TA - International tourism arrivals). The study is an attempt to estimate the short-run and long-run relationship between terrorism and FDI, as well as terrorism and inbound tourism by applying ARDL techniques for the period of 1995 to 2016. The ARDL bound test justifies the co-integration between terrorism, FDI and tourism. Moreover, the estimated results clearly indicate the negative short-run and long run impact of terrorism on FDI and terrorism on tourism. Furthermore, our findings also concur that terrorism has a huge impact on FDI as compared to tourism. Finally, the estimates confirm a unidirectional causality from terrorism to FDI and from terrorism to tourism.

Keywords: Terrorism incidence, Tourists arrivals, FDI, ARDL methods and Granger causality

Cite this paper: Mir Alam, Ye Mingque, The Relationship between Terrorist Events, Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) and Tourism Demand: Evidence from Pakistan, American Journal of Tourism Management, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2018, pp. 10-18. doi: 10.5923/j.tourism.20180701.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

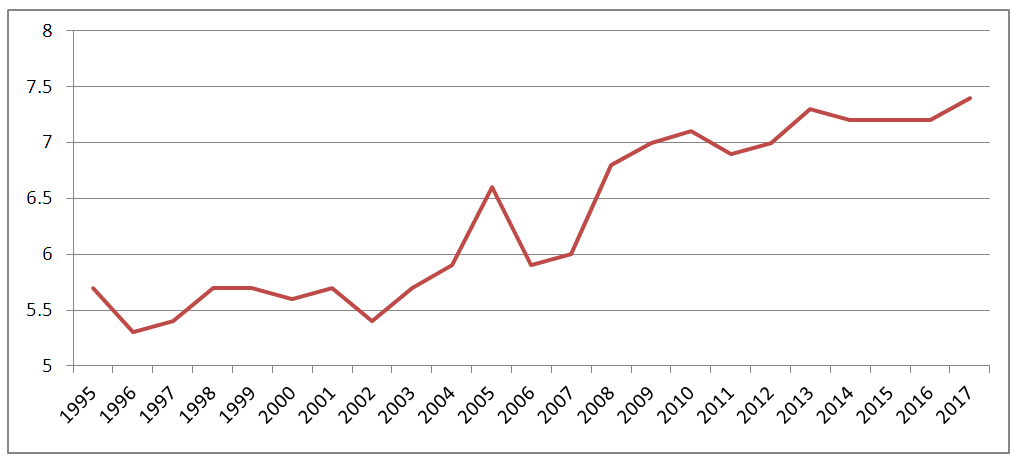

- Since the start of the 21st century, it has been observed a substantial increase in terrorist events across the world. These events are generally a part of universal cold wars. However, its relations with indigenous political problems cannot be denied. Pakistan has been facing with terrorism since its inception from 1947. Pakistan has lost its first prime minister in a terrorist incident. In the initial stage Pakistan was dealing only sectarian violence. Gradually, it has targeted the common citizens of the country. With the passage of time terrorism has been impaled almost all regional and ethnic groups. Moreover, there are various reasons of terrorism in Pakistan, religious extremism, poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, unequal distribution of wealth, misuse of Jihad, lack of rule of law, etc. However, terrorist event has been seen significantly increase after 9/11 incident. As a result of being a non-NATO member Pakistan has come under the direct threat of terrorism. And now, Pakistan is among top 5 most impacted countries by terrorism. Terrorists incidence creates uncertainty, anxiety, insecurity and panic in the overall atmosphere of the country [1, 2]. According to latest [3], global terrorism has been declined its intensity yet its continue to spread to more countries. In 2016, there were 77 countries that experience at least one casualty due to terrorism; this is highest in the last 17 years. However, this is 22% fewer casualties/deaths from terrorist attacks since 2014, which was the peak year of the terrorist incidence. Despite completely indulged by terrorism, tourism sector of Pakistan is performing at a satisfactory level. The tourism sector has a reasonable direct and indirect impact in Pakistan’s economy, with a sensible growth. The total contribution of the sector to GDP of Pakistan was 5.3% in 1996 and rose to 7.4% in 2017. The direct contribution of the sector in 2016 was PKR793 billion Pakistani rupees (7.6billion UD$), which is 2.7% of total GDP while total contribution of the industry to GDP is 19.4 billion US$, 6.9% of total GDP [3]. Figure 3.1 shows the contribution of the tourism sector to GDP of Pakistan from 1995 to 2017. It is moving on a positive track after 2006. The primary objective of both inbound and domestic tourists was leisure and business. In 1996, the contribution of leisure spending and business spending was 84% and 16%, respectively. However, the contribution of inbound tourism is still very low as compare to domestic tourism. The contribution of inbound tourism was 7.4% whereas. Domestic tourists share is 92.6$. Through attracting foreign tourists, tourism sector subsidizes the economy of the home country by contributing in capital formation [4]. And the aggregate contribution of travel and tourism to total capital investment is 9.3% and the contribution of total exports is 3.6% in 2016 [3].

| Figure 3.1. Percentage contribution of tourism industry to GDP od Pakistan. [3] (Source: World Travel & tourism council (WTTC, 2017), own calculations and compilation) |

2. Literature Review

- A sufficient number of empirical studies exist that has been examined the impact of tourism on different macroeconomic indicators in different countries for both time series and panel data. The majority of the empirical studies estimated the association between inbound tourism and economic growth. Yi-Bin and Lung-Tai [8], Tugcu [9], Shahzad, Shahbaz [10] and Lee and Chang [11] have found a positive impact of tourism on economic growth. Zeng and Gerritsen [12] and Leung, Law [13] analyzed the role of social media while selecting a particular tourist destination. There are plenty of studies in tourism literature that have discussed the driving forces that motivate the international visitors to pick the best place to spend leisure time. Buhalis [14] and Ismagilova, Safiullin [15] propose that the historical heritages and cultural resources are key factors that attract tourists to choose the tourists destination. Webster and Ivanov [16], Soemodinoto, Wong [17], Saha and Yap [18] and Poirier [19] have discussed the importance of political stability in international tourism. They also display how a well performing tourism industry can be an engine to reduce political instability. Neumayer [20], Li and Song [21] and Lee, Song [22] have examined the different hurdles that can retard the flow of inbound tourist to a particular country or group of countries. They found that the visa restriction is another important impediment for selections of tourist destinations.In tourism literature, studies related to the effect of terrorist incidence on the tourism industry are primarily focused on analyzing the decrease in the number of tourists flow, the reduction in tourists’ receipt and the progressive structure of the effect of terrorism. Although using different methodologies, the ultimate conclusion endures the adverse effect of terrorism on the tourism sector and the overall economy of any country. Previous literature truly pointed out that international tourists are not reluctant safety; their reactions to the terrorist events are quite natural and decide to travel to a safe and secure tourist’s destination. Consequently tourism sector declines and damage the economy of any country. [23-30]. Some latest studies estimate the causality and established the unidirectional causal negative relation from terrorist’s incidence and tourism. Few of them Samitas, Asteriou [31] for Greece, Bhattacharya and Basu [32] and [33] for India, [34] and [2] for middle east, Hamadeh and Bassil [35] examine for Lebanon and Lennon and O’Leary [36] for Germany. Similarly, Trindade [37], analyze the effect of terrorist attacks in Turkey and Egypt on tourism of Portugal. And found a positive impact. This indicates that international visitors always try to find the alternate destination if terrorism is occurring in a particular country. However, a recent study Liu and Pratt [38] estimate the short-run and long run effects of terrorism on tourism for the panel of 95 countries. He evidence that only 9 countries have long-run impact of terrorism on tourism while only 25 countries have short-run impact using time series analysis. Furthermore, according to Fleischer and Buccola [39] the influence of terrorism to domestic tourism higher than the impact of terrorism to international tourism. They further argued that inbound tourism is more sensitive to relative prices. In addition, there is a plenty of studies in the literature on the impact of terrorism on foreign direct investment (FDI). However, we found enough studies on the influence of tourists’ event on other macroeconomic indicators in different countries. FDI depends on investors’ attitude to face the different risks. Since terrorists’ incidence creates unrest, anxiety, uncertainty in the economy of any country, consequently, multinational investors take advantage of diversified opportunities and prefer to invest in a safe country. So, terrorism has a negative impact on FDI. In other words, it is noticed that terrorist’s incidence influenced capital allocation globally. The attractiveness of international investors toward any country is affected by the terrorism [40-45]. In contrast, the findings of some studies are opposite and ambiguous. They argue that terrorism is not a highly effective factor that affects FDI. Additionally, the effect of terrorism on FDI varies from country to country. Enders, Sachsida [46], examine the impact of terrorism on FDI; he got evidence of a negative significant impact of terrorist events on FDI in OECD member countries whereas, insignificant in non-OECD member countries. [47, 48], [49] and [50] estimated the impact of terrorism on FDI, and found neutral results. Means that terrorist’s incidences are not significant to FDI inflow.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

- Annual time series data from 1995 to 2016 is considered in this study. The variable terrorist incidence (TI) is drawn from [51]. TI is all kind of annual number of terrorists attacks occur in the country. Proxies foreign direct investment (FDI) inflow to Pakistan, which is in current US dollar, and international tourism arrivals (TA) are driven from the world bank database, world development indicators [52]. All the variables are transformed into log form. The log values can convert the observation from skewed to normal form; it can also convert the relationship between dependent and independent variable from the rate of change into percentage term.

3.2. Unit Root

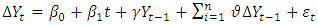

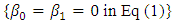

- The main idea underlying in the process of time series is stationarity. The time series would be considered covariance stationary when it must have following three characteristics. (a) it must exhibits mean reversion means that it fluctuation must be constant over the same period of time in the long run (b) it must has a finite variance which is time-invariant over the period of time (c) and the series must have a theoretical correlogram as geometrically decayed, as we increase the lag length then it diminishes. In such a case, we said to be stationary in time series Yt if:E (Yt) =constant for all t; (b) Var (Yt) =constant for all t; and (c) Cov (Y1, Yt+k> =constant for all t and all k t= 0, concluding that, if the mean, variance and covariance over the fixed over the time is. The integration of the time series as well as distinction between stationary and non-stationary process is dependent on the reliability of statistical inference. Due to constant variance and mean the shock to a stationary time series is momentary over the period of time. In addition as far as non-stationary time series is concerned, then its mean and variance is time varying to permanent fluctuations over the period of time. Based on this, it is important to be considering the all three characteristics of time series, it is mandatory to check the properties of stationarity of a variable by using its appropriate order of integration. For the purpose to check stationary, there are various tests have been proposed to determine order of integration of the variables. These tests include Augmented Dickey-Fuller, Phillips-Perron and Ng-Perron tests. However, Augmented Dickey-Fuller [53] and Phillips-Perron [54] are used in this study. Following is the equation for the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test

| (1) |

is difference operator,

is difference operator,  (either terrorism or FDI or tourism) is the series under estimation,

(either terrorism or FDI or tourism) is the series under estimation,  is the stationary random error term, n is large enough to confirm that

is the stationary random error term, n is large enough to confirm that  is the white noise method. The lags (n) number to be identified applying Akaike Information Criteria (AIC).

is the white noise method. The lags (n) number to be identified applying Akaike Information Criteria (AIC).  (Null hypothesis) of

(Null hypothesis) of  being non-stationary is estimated against the

being non-stationary is estimated against the  (alternative hypothesis) of stationarity. When the estimated coefficient

(alternative hypothesis) of stationarity. When the estimated coefficient  is statistically significant negatively, and then

is statistically significant negatively, and then  is rejected. The estimations take 3 alternative forms, Unit root (i) with a time trend and intercept as Eq (1), (ii) no trend but with an intercept

is rejected. The estimations take 3 alternative forms, Unit root (i) with a time trend and intercept as Eq (1), (ii) no trend but with an intercept  and (iii) with no trend, no intercept.

and (iii) with no trend, no intercept.  Phillips-Perron(P-P) test is an alternate test. P-P test takes the form:

Phillips-Perron(P-P) test is an alternate test. P-P test takes the form: | (2) |

when the coefficient of

when the coefficient of  is negatively significant then

is negatively significant then  of non-stationarity is rejected. Likewise to ADF test the Phillips-Perron(P-P) test has also 3 different forms.

of non-stationarity is rejected. Likewise to ADF test the Phillips-Perron(P-P) test has also 3 different forms.3.3. ARDL Bound Testing Approach

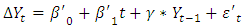

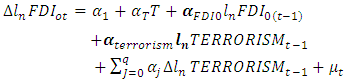

- In the analysis of the time series, many approaches, based on long run and short run relationship have been developed; including, Johansen co-integration test (1990), Engle and Granger cointegration approach (1987), Phillips and Ouliaris (1990) and ECM based t-test of Banerjee et al. (1998), Error Correction Model (ECM) based F-test of Boswijk (1994). However, for these all models and techniques all variables should be integrated of order one 1 that id 1st difference. On the other hand, to increase the cointegration power and the relationship between variables in time series, Pesaran et al. (2001) have introduced the approach of Auto regressive distributive lag model (ARDL) bound test, and this test is acceptable by different orders of integration such as either I(0) or I(1) or I(0)/I(1). But this approach does not require the 2nd order of integration i.e. I(2). However, for the purpose estimating the effects of terrorism events on foreign direct investment FDI and Truism in Pakistan we have formulated the following two ARDL Bound testing models;

| (3) |

| (4) |

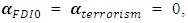

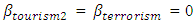

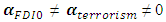

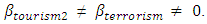

also

also  and similarly for the alternative hypothesis

and similarly for the alternative hypothesis  and

and  In this connection, the null hypothesis presents that there is no co-integration exist between dependent and independent variables. On the other hand, the alternative hypothesis presents that there exists co-integration relationship between dependent and independent variables. In such a case, if the estimated value of F-Stats exceeds the Upper critical bound value, we may reject

In this connection, the null hypothesis presents that there is no co-integration exist between dependent and independent variables. On the other hand, the alternative hypothesis presents that there exists co-integration relationship between dependent and independent variables. In such a case, if the estimated value of F-Stats exceeds the Upper critical bound value, we may reject  and the result would indicate there is no existence of co-integration, otherwise we may accept the null hypothesis. Additionally, if the estimated value of the F-statistics is existing between (LCB) and (UCB), we would conclude that the estimated results are inconclusive and uncertain.

and the result would indicate there is no existence of co-integration, otherwise we may accept the null hypothesis. Additionally, if the estimated value of the F-statistics is existing between (LCB) and (UCB), we would conclude that the estimated results are inconclusive and uncertain.3.4. Granger Causality

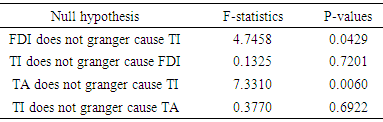

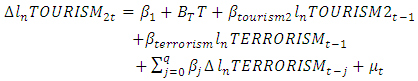

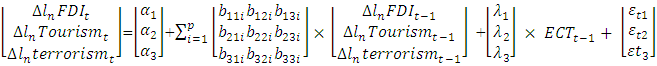

- When we are confirmed the existence of the long-run relationship between dependent and independent variables, then we preceded the approach of Granger causality because it is necessary condition in the directions of causality among foreign direct investment, tourism and terrorism. This approach has been developed by, Engler and Granger (1987) as an approach to detect causality between under studied variables. Later on, this approach has been modified into Vector Error Correction Model into short and long run. However, the estimated Vector Error Correction Models for foreign direct investment, terrorism and tourism are as follows;

| (5) |

This term would represent the speed of adjustment, as once it deviated from its original path then at what speed it adjusts to its original path. In this connection, the conclusion regarding the existence of long run would be drawn when the coefficients of

This term would represent the speed of adjustment, as once it deviated from its original path then at what speed it adjusts to its original path. In this connection, the conclusion regarding the existence of long run would be drawn when the coefficients of  will be significant statistically. Similarly, the significance of

will be significant statistically. Similarly, the significance of  Coefficients predicts short run association among variables.

Coefficients predicts short run association among variables.4. Empirical Results and Discussions

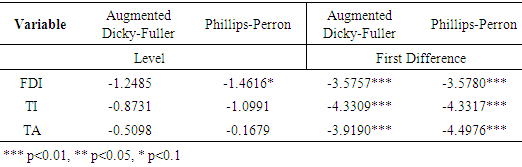

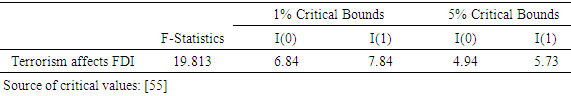

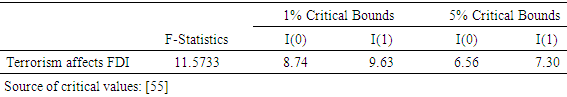

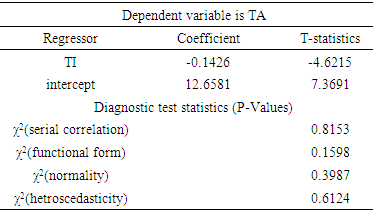

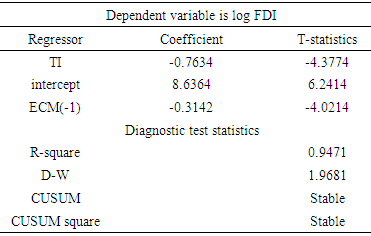

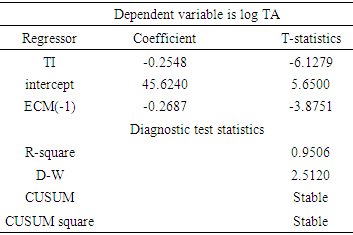

- One of the main advantages of applying Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model is that ARDL can be applied without considering the data series which is stationary either at level or first difference or in both. However, according to Pesaran, Shin [55] it is clearly mentioned that ARDL estimates are not valid when the data is stationary at second difference. That is the series that is generated by I(2). Consequently, to test the level of statioarity, we use Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Phillips-Perron (PP) estimates. The results of ADF and PP are displayed in Table 3.2. It is evident from Phillips-Perron and ADF estimates that some of the variables are stationary at I(0) or I(1). Almost all the variables are stationary at I(1) according to both of the estimators. Additionally, it is also evident that none of the variable is stationary at I(2) or above, which is the basic condition of using the ARDL model. Therefore, it is justified to use ARDL estimators.After the confirmation that all the variables are integrated at either I(0) or I(1). ARDL bound test technique for estimating the long-run relationship between FDI and terrorism and between Tourism and terrorism.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

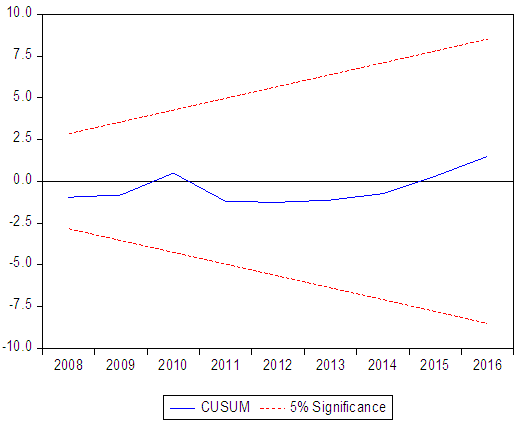

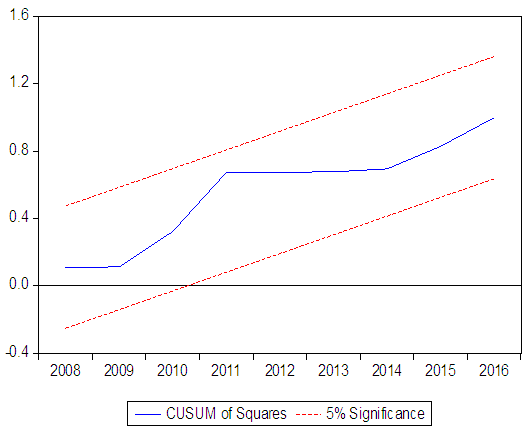

| Figure 3.2. Plots of CUSUM statistics, between FDI and TI |

| Figure 3.3. Plots of CUSUMSQ statistics, between FDI and TI |

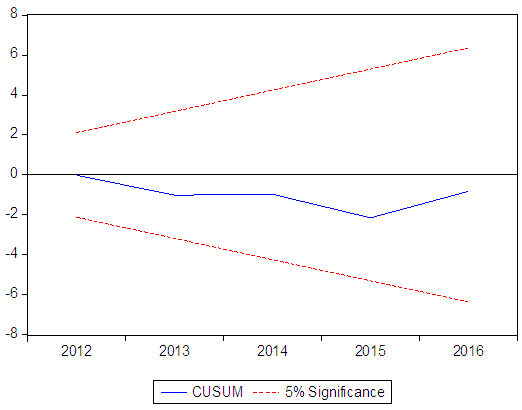

| Figure 3.4. Plots of CUSUM statistics, between TA and TI |

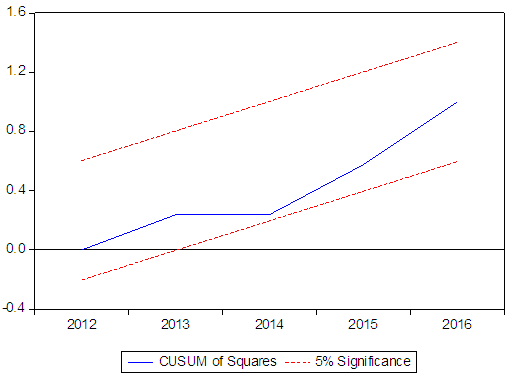

| Figure 3.5. Plots of CUSUMSQ statistics, between TA and TI |

|

5. Conclusions

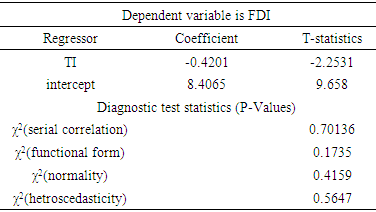

- A plethora of studies exist in the previous literature, which addresses the impact of terrorism on FDI and tourism. However, the comparison of the intensity of the effect of terrorism on FDI and on tourism is totally missing. This empirical work analyzes the relationship between FDI, terrorism and tourism in Pakistan using annual data from 1995 to 2016. Estimates justify the cointegration between terrorism, FDI and tourism demand. The outcomes of the study also confirm a long-run and short-run relationship among FDI, Terrorism and tourism in the case of Pakistan. The results of the study validate the negative impact of terrorism on FDI and inbound tourism. We apply Autoregressive Distributed lagged (ARDL) model to settle these outcomes because of its numerous advantages over the other models. It is observed that in the long run a 1% increase in terrorists’ incidence leads to decrease FDI 0.42% FDI and 0.14% TA. The results are robust in the estimates for short-run. In short-run with a 1% increase in TI leads to decline 0.7% and 0.25% TA. Consequently, we can conclude that the influence of terrorism in short-run is greater than its impact in the long-run. And the influence of terrorism on FDI is greater than the impact of terrorism on inbound tourism. These empirical evidences, justify that the foreign investors have dual threats. The face life threat and fear of losing the investment. Therefore, FDI is more sensitive to terrorism as compare to inbound tourism.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML