-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Tourism Management

p-ISSN: 2326-0637 e-ISSN: 2326-0645

2015; 4(1): 7-17

doi:10.5923/j.tourism.20150401.02

Why They Go There: International Tourists’ Motivations and Revisit Intention to Northern Ghana

Frederick Dayour 1, Charles Atanga Adongo 2

1Department of Community Development, University for Development Studies, Wa, Ghana

2Department of Hospitality and Tourism Management, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana

Correspondence to: Frederick Dayour , Department of Community Development, University for Development Studies, Wa, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The interrelationship among motivations, satisfaction, and revisit intentions remain largely unexplored. Therefore, the purpose of the study was to facilitate understanding on the relationship among these constructs. A survey of 650 international tourists shows that four key factors: culture, destination attractions, social contact and adventure-novelty influence tourist decision to visit northern Ghana. The study established that tourists’ motivation has relationship with their satisfaction; likewise, satisfaction is a determinant of their revisit intentions. It is recommended that service providers and destination managers should work at ensuring tourists satisfaction in order to ensure repeat visits.

Keywords: Motivations, Satisfaction, Revisit intention, Tourists, Northern Ghana

Cite this paper: Frederick Dayour , Charles Atanga Adongo , Why They Go There: International Tourists’ Motivations and Revisit Intention to Northern Ghana, American Journal of Tourism Management, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2015, pp. 7-17. doi: 10.5923/j.tourism.20150401.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Since time immemorial, travel motivation is one of the most researched themes in the tourism literature. This is seen in the light of theoretical advancements by scholars, such as Maslow (1943), Gray (1970), Dann (1977, 1981) and Crompton (1979). Phenomenal growth in research on this subject in recent times has also seen an increase (Jayarman, Lin, Guat & Ong, 2010; Agyeiwaah, 2013; Otoo, 2013; Dayour, 2013). Literature posits that people travel because they are pushed into making travel decisions by psychological forces which are innate, and pulled by the destination attributes (Crompton, 1979; Prayag & Ryan, 2010). Therefore, travel satisfaction with travel experiences, based on these push and pull forces, contributes to revisit intention (Pratminingsih, Lipuringtyas & Rimenta, 2014). Ghana is one of the relatively competitive destinations in the West African sub-region attracting appreciable tourist numbers (Ghana Tourism Authority [GTA], 2014). Broadly, Ghana is divided into the southern and northern belts, of which the latter contributes significantly to the drawing power of the destination owing to the wide range of ecological and cultural attractions it wields (GTA, 2013). Akyeampong (2007) posits that tourists who visit northern Ghana are mostly repeat visitors. On that account, there should be some reasons why international tourists would like to visit northern Ghana and probably, their revisit intentions. These key issues have remained elusive to researchers in Ghana, hence constitute a knowledge hiatus that requires investigation into in order to add information to what pertains to Ghana and by extension West Africa. This paper, therefore, examines the factors that motivate tourists to travel to northern Ghana, and the extent to which these motivations influence their satisfaction and revisit intentions. Thus, the study is to present a holistic approach to understanding tourist motivation and also explore the theoretical and empirical evidence on the causal relationships among motivations, satisfaction, and revisit intention. Consequently, this study is expected to contribute to the existing body of knowledge by first highlighting the factors that underlie tourists’ visits to northern Ghana. Second, it will also explore the extent to which tourists’ motivations influence satisfaction. Finally, the study estimates the influence of travel satisfaction on repeat visit. Tourist motivation is a precursor to destination selection hence insight on destination choice determinants would go a long way aiding service providers, especially tour operators and travel agents in packaging tailored tours to prospective tourists. Again, considering the marked competitive strive by destinations for the tourist dollar with each presenting itself as the ultimate entity through which the vacation requirements of the tourist can be met, understanding the motives behind an individual’s purchase behavior marks the core basis upon which sound market appraisals can be built by destination marketing organizations. This is especially true for the branding of northern Ghana since the National Tourism Policy Document (2013-2027) acknowledges that at present, Ghana’s market position is not strong, mainly suffering from an unclear market image abroad. More importantly, Um, Chon and Ro (2006) acknowledge that it is one good thing for a destination to attract a tourist and another how to maintain him or her. This is even more central in the tourism trade since repeat visits are rear, making customer relationship management the most pursued strategy by destinations. Larson and Chow (2003) aver that understanding the relationship between tourist motivations and their revisit intentions is a good starting point for customer relationship management.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Motivation

- Obviously, to every visit away from home there is a driving motive (Mak, Wong & Chang, 2009). Motivations mirror an individual’s intrinsic and extrinsic travel needs and wants (Kim, Sun & Mahoney 2008). An appraisal of the literature on tourist motivations for visiting destinations present a number of common broad factors including novelty seeking (Mansfeld, 1992; Rittichainuwat, 2008; Ooi & Laing, 2010), search for cultural experience (Kim, Eves & Scarles, 2009; Amuquandoh, 2011), adventure (Mak, Wong & Chang, 2009; Niggel & Benson, 2007; Prayag & Ryan, 2010), social contact (Pearce & Lee, 2005; Grimm & Needham, 2012) escape from routine environments (Mak, Wong & Chang, 2009; Niggel & Benson, 2007; Prayag & Ryan, 2010), relaxation (Jonsson & Devonish, 2008; Hsu, Cai & Li, 2010) and destination’s attractions (Park & Yoon, 2009; Dayour, 2013; Pratminingsih, Lipuringtyas & Rimenta, 2014; Grimm & Needham, 2012). These are in line with the argument that tourist motivations are multifaceted and may go hand-in-hand with each other rather than in isolation. This plethora of tourist motivations is tersely captured by Dann (1977) as push-pull factors. Whereas the push motives explain tourist desire to travel, the pull motives rather explain the choice of destination relative to its attributes (Dayour, 2013). Novelty seeking is one of the reasons why tourists visit a destination. The literature considers novelty as the degree of contrast between the known and unknown, making it the opposite of familiarity that leads to little or no experience. Novelty seeking is an inner urge that stimulates individuals to engage in observation, exploration, manipulation, and questioning (Park, Andrew & Mahony, 2008). Desire to acquire new knowledge and new sensory experiences are central to tourists in search of novelty (Trauer & Ryan, 2005). McIntosh, Goeldner and Ritchie (1995) and Park, Mahony and Kim (2011) put forward various sources of novel experiences, ranging from the discovery of nature-based attractions, events and activities, innovative physical places, to the gaining of prestige and attention from others. However, the psychocentric tourists tend to favour familiar destinations unlike their allocentric counterparts who want to experience the unknown. This means that individuals vary in terms of destination seeking behaviour (Elsrud, 2001). It is, therefore, possible that certain attributes of northern Ghana may attract some tourists and equally fend off others.The second motivational rubric is cultural experience. According to existing literature, this is taking a trip to celebrate cultural diversity which involves looking outside for what individuals cannot find inside (Mansfeld, 1992). The need to participate and learn about a destination’s local culture including rituals, values, music and dance constitute cultural motivations. Kim and Eve (2012) and Hjalager (2003) have also highlighted travel for local food experience as a cultural motive. Hjalager (2003) observed that during holidays, eating and drinking a particular local food and beverage respectively, means sharing the local food culture. Proceeding from that premise, tourists travel for unusual and daring experiences has also been identified in the literature. This is mostly termed adventure tourism (Callander & Page, 2003; Bigne, Sanchez & Andreu, 2009). This however, as an attempt, has added to the imprecise phrases and definitional struggles associated with the concept of tourism. Adventurous experiences include the search for exotic or wilderness destinations, undertaking heroic outdoor activities, and the inherent risk pursuit of such activities (Park, Mahony & Kim, 2011 & Godfrey, 2011). The apparent reality of the latter presents the rhetorical question, what is the level of tolerance of such risk? All the same, Stoddart and Rogerson (2004) found that the top motivator of tourist visit to South Africa is adventure. Another broad factor contributing to tourists travel is the need for social contact. Inherent in every social interaction is the likelihood of friendship. Tourism is an avenue that brings together people with different cultural backgrounds that may lead to friendship (Brown & Lehto, 2005). Dayour (2013) asserts that travel to destinations is an opportunity to meet and communicate with others. This affirms the findings of Pollard et al. (2002) and Hallberg (2003) who are of the view that social contact is the desire to spend time with family and/or friends as well as a need to meet new people beyond the normal circle of acquaintance.According to Jarvis and Peel (2010), the desire to travel is often associated with the yearning to escape. That is to “break from routine” activities of the home and work (Kim & Ritchie, 2012). This break affords people the opportunity to refresh their minds by engaging in non-routine forms of leisure activities (Ritchie, Tkaczynski & Faulks, 2010). Closely related to escapism is the travel for relaxation. It has to do with resting from one’s day-to-day activities. It is also seen as a state of being liberated from tension and anxiety (Grimm & Needham, 2012). Leonard and Onyx (2009) found that relaxation aside escape is the most central psychological predisposing factor for tourist movement. Finally, destinations’ attraction is a pull factor. The attractiveness of a destination largely depends on its unique attractions which could be a place, phenomenon or event (Maoz, 2007). Attractions assume the form of natural or man-made phenomena and are the main motivations for travel (Cooper, Fletcher, Fyall, Gilbert & Wanhill, 2008). Arguing from the standpoint of tourist activities, Akyeampong and Asiedu (2008) allude to the fact that tourists are always in the quest for active and passive activities ranging from sight-seeing, learning, safari walks, mountain climbing, art and craft appreciation among others. Gunn (1972) concludes that attractions constitute a destination without which there will be no tourism. The contrary is also true anyway.

2.2. Satisfaction and Revisit Intention

- Satisfaction can be described as the fulfillment gained by a tourist after consuming a product or service (Oliver, 1997). Chi and Qu (2008) and Santouridis and Trivellas (2010) maintain that satisfaction is a significant determinant of repeat visit. Similarly, previous studies have also suggested that when tourists’ holiday expectations are met or exceeded, they are more likely to return in the future (Chen & Tsai, 2007; Oliver, 2010; Som, Marzuki, Yousefi & Khalifeh, 2012). Chi and Qu (2008) and Santouridis and Trivellas (2010), for instance, observed that overall satisfaction on travel experience is a major antecedent of revisit intention. However, Bigne, Sanchez and Andreu (2009) argue that in a competitive market even satisfied patrons may switch to rivals because of the opportunities to achieve better results. Based on these findings, this study puts forward that satisfaction with trip experience would have a positive influence on tourists’ revisit intention to Northern Ghana.

2.3. Conceptual Framework

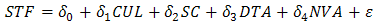

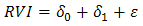

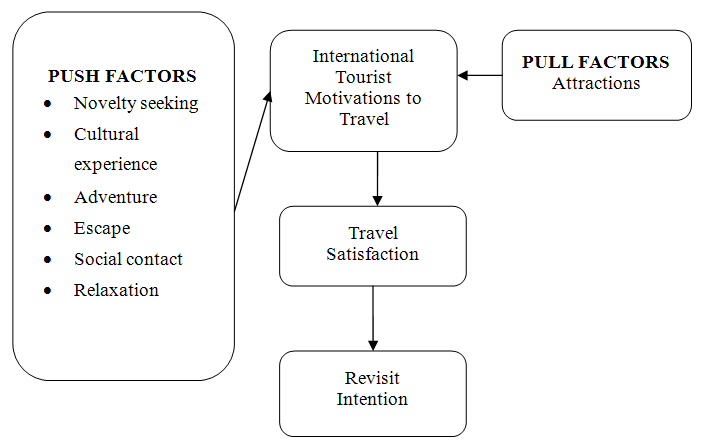

- A conceptual framework by Yoon and Uysal (2005) was adapted to guide the course of the study (Figure 1). The framework was found appropriate because it provides some key variables which are germane to the current study. The basic argument advanced by the proponents is that tourist visitation to a particular destination is a function of the push and pull factors. Accordingly, the push forces constitute the internal emotional desires of the tourist including novelty seeking, culture experience, adventure, escape, and relaxation among others whereas the pull factors are those forces that define the tourist choice of a destination (e.g. scenery, cities, climate, wildlife, historical and local cultural attractions). They are largely destination specific enticing elements. Therefore, collectively the two generic factors explain why a person would want to embark on travel and where he or she would go to satisfy this need. Consequently, just like a product, whenever tourists are satisfied with travel experience in a particular destination, it has both the short run and the long run behavioral effects, of which revisit intentions is one (Hutchinson, Lai & Wang, 2009; Santouridis & Trivellas, 2010). The apriori theoretical models for the study are depicted by equations 1 and 2.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| Figure 1. Framework on tourists’ motivations and revisit intentions. Source: Adapted from Yoon and Uysal (2005) |

2.4. Study Setting

- The survey was conducted on international tourists who visited northern Ghana. The area is made up of three (3) main regions (viz. the Northern Region, Upper East Region and Upper West Region) which are part of the ten (10) administrative regions of Ghana. It is noteworthy that the Northern Region is the biggest in terms of land size. The other two regions were hitherto called the Upper Region, but in pursuance of a decentralization policy, the Government of Ghana, in 1983, split the Upper Region into Upper East and Upper West Regions. Northern Ghana is bordered to the north by Burkina Faso, to the east by Togo and to the West by Burkina Faso and Cote d’ Ivoire. Together, northern Ghana covers a geographical area of approximately 70,384 square kilometers. Climatically, the area experiences two (2) distinct seasons - the dry and wet seasons. The vegetation cover is guinea savannah grassland with medium size trees and consists mainly of drought and fire resistant trees, such as baobab, dawadawa, shea-tree and acacia. As regards tourist attractions, the region is home to a gamut of ecological and cultural attractions, such as the Mole National Park, the Larabanga Ancient Mosque and the Mystic Stone, the Gambaga Escarpment, Paga Crocodile Pond, the Whistling Rocks, the Navorongo Cathedral, the Wichau Hippotamus sanctuary, the Wa Naa’s palace, Wulin Mushroom rock, Gbelle Game reserve and the Nakore Mosque. The region is also endowed with unique cultural attributes in relation to festivals, language, ethnic groups, clothing, food and beverage and architecture which are somewhat different from those of the south. The destination experiences a considerably high number of tourist arrivals each year (GTA, 2013).

3. Methods

- The data for the study were collected primarily from international tourists who visited northern Ghana. The justification for targeting international tourists is that these tourists might be visiting the region for a special reason, given that they are nationals from other countries outside Ghana. This argument is not meant to trivialize domestic tourists’ motivations for visiting the area, but perhaps, the ‘foreigner’ who is by description a noncitizen may have some unique reasons for visiting the unknown, which are worth exploring, hence the rationale for the choice. The data collection lasted for 5 months at three (3) main attractions located within the three (3) regions of the north (between May and September, 2013) through the use of a questionnaire. They included the Mole National Park of the Northern Region, Paga Crocodile Pond of the Upper East Region and the Wichau Community Hippopotamus Sanctuary of the Upper West Region. These three (3) attractions are by far the most visited attractions in the three regions of the north (GTA, 2013). The said attractions were covered consecutively one month apart from each other. This was to control for double counting, since tourists spend much time in these cities and that their average length of stay is no more than 14 days. Moreover, tourists were also asked whether or not they were interviewed on the same subject before.A total of 700 respondents were contacted using the systematic sampling method of data collection, of which 300 were from the Mole National Park, 200 from Paga Crocodile Pond and 200 from the Wichau Community Hippopotamus Sanctuary. These sub-samples were proportionately allocated based on tourist arrivals to the attractions. The questionnaire approach to data collection was adopted because the target audience was predominantly literate and could read and write in English language. The questionnaire was divided in three modules as follows: the first part examined tourists’ motivations (measured on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from agrees to disagree) for travelling to the destination, using measurement items adapted from previous studies. The second module consisted of questions on the tourist overall satisfaction (measured with 5-point Likert scale: very dissatisfied to very satisfied) and revisit intention (dummy outcome). Lastly, the third module captured the background characteristics of the respondents, such as sex, age, marital status, educational qualification, religion, occupation and continent of origin. The instrument was pretested in Cape Coast on 60 tourists to validate it. This exercise resulted in the removal and rewording of some questions and statements that sounded ambiguous and irrelevant. Out of 700 questionnaires that were administered to tourists, 650 were found valid and usable, representing a response rate of 93%. Data collected from the field was processed using the Statistical Product for Service Solutions (SPSS, version 20). The exploratory factor Analysis (EFA) was used to explore the main factor-solutions or dimensions that explain international tourists’ motivations for travelling to northern Ghana. The reliability of the scale was tested using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Furthermore, the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression technique was used to estimate the influence of tourists’ motivations on their overall satisfaction, likewise the Binary Logistic regression was used to test the influence of tourists’ satisfaction on their revisit intention to northern Ghana.

4. Results

4.1. Background Characteristics of Respondents

- It was found that almost the same proportion of males (49.5%) and females (50.5%) participated in the study. On marital status, the majority (82.6%) of the respondents were unmarried while a few (17.4%) were married. Also about 45.7% of tourists were below age 20 while about a third (32.9%) of them were between the ages of 20-29. Those who were aged between 30-39 years were in the minority (6.2%). The average age of respondents was however, found to be 24 years. With regard to educational qualification, 34.6% of them were degree holders, while 32.5% had had their secondary education. Those who had diploma (17.5%) and postgraduate (15.4%) qualifications were in the minority. About three-quarters (74.8%) of them said they were Christians, 18.7% were Atheist and only 6.5% said they were Muslims. Lastly, it was observed that almost two-thirds (57.7%) of the respondents were from America while 37.3% were from Africa. The minority of them came from Europe and Asia representing 4.4% and 0.6% respectively.

4.2. Tourists Motivations for Travelling to Northern Ghana

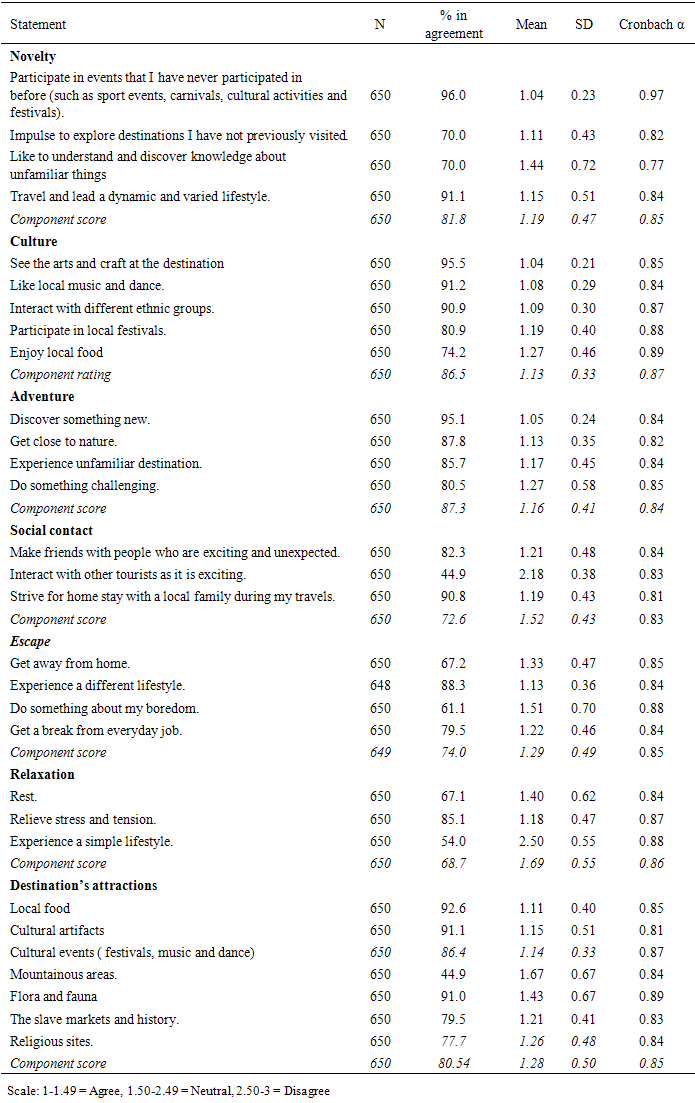

- The study sought to examine the motivations of tourists who visited northern Ghana. Table 1 shows the actual mean scores and the standard deviations on items under each component. It was obvious from the survey that 81.8% of the respondents travel to northern Ghana in quest for novelty. For most (96.0%) of them, participation in new events was their reason for visiting. Another 70.0% of them did say they travelled to northern Ghana because they wanted to explore unfamiliar things. Further, 91.1% did indicate that they wanted to have a dynamic and a varied lifestyle.

|

4.3. Components Accounting for Tourists’ Motivation to Travel to Northern Ghana

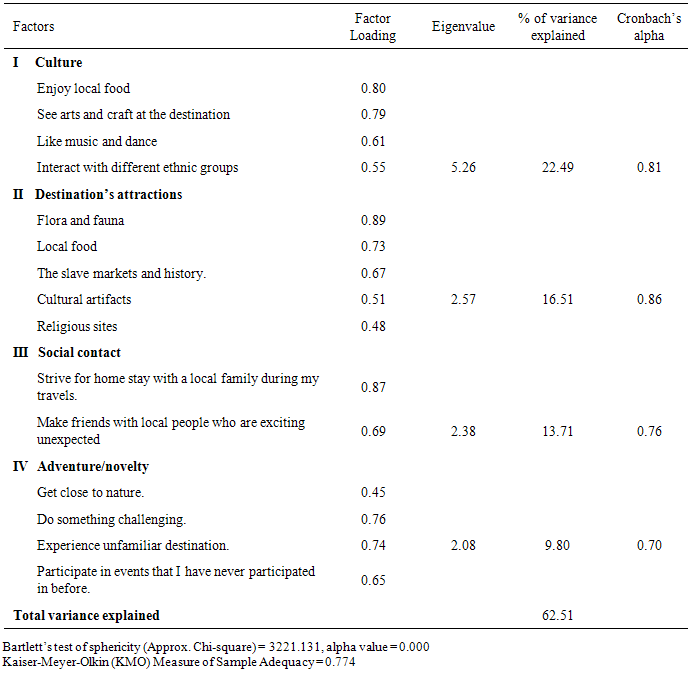

- After the assessment of respondents’ reactions to individual variables on motivations using basic descriptive statistics, an EFA was performed on 31 items to identify the factors that motivated international tourist to visit northern Ghana (Table 2).

|

4.4. Predictors of International Tourist’s Overall Satisfaction in Northern Ghana

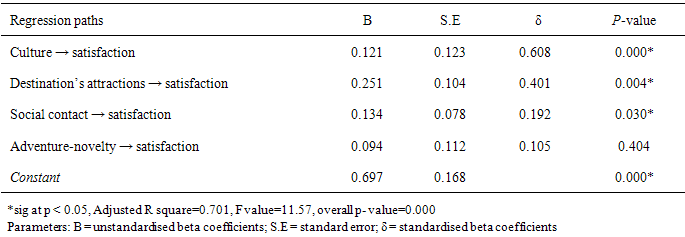

- The OLS regression model was used to explore the influence of tourist motivations on their overall satisfaction in northern Ghana, using a 0.05 statistical significance measure (Table 3). The results showed that 70% of the variation in overall satisfaction was explained by motivation. Hence, in descending order of magnitude, culture (δ1 =0. 608), destination’s attractions (δ2 = 0.401), and social contact (δ3 = 0.192) were considered significant determinants of the overall satisfaction of tourists in the destination.

|

4.5. Influence of Satisfaction on Revisit Intention

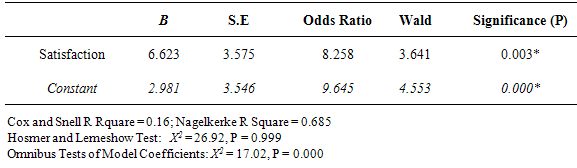

- Subsequently, a binary logistic regression model was employed to determine the influence of international tourists’ overall experience on their revisit intentions. The technique was used following a recommendation by Sweet (1999) and Pallant (2005) that it is the most appropriate tool for a dichotomous dependable variable. Thus, the outcome variable which is the revisit intention was recoded into a binary function of 0 and 1. Therefore, the possibility of revisit intention was 1 while the absence 0. The output is shown in Table 4. The logit model emerged as a good predictor of international tourists’ intention to revisit northern Ghana as shown by the Nagelkerke R square of 0.685. The results indicated that tourists who were satisfied with their overall experiences in northern Ghana are 8 times more likely to revisit than those dissatisfied.

|

5. Discussion

- Results of this study indicate that issues of culture, destination’s attractions, social contact and adventure-novelty are the underlying factors that define tourist motivations to visit northern Ghana. As regards the need for cultural experiences, Mansfeld (1992) and Kim & Eves (2012) indicate that the need to participate and understand the culture of other regions is an important factor that pushes people to travel. It is, therefore, expected that this factor emerged as the main determinant of tourists’ decision to visit Northern Ghana. The destination’s attraction was yet another factor that emerged as a motivation for tourists visiting the north. This observation lends further credence to the centrality of destination’s attributes in attracting tourist. Cooper, Fletcher, Fyall, and Wanhill (2008) assert that attractions are the main motivations for travel to various destinations. According to Brown and Lehto (2005), tourism brings people with different cultural and geopolitical landscapes together for the purpose of camaraderie. Based on the aforementioned, the finding on social contact as a motivational factor is not so strange because tourists as part of their holiday experiences desire to meet with and interact with local families and other travellers. The results of the study also suggest that adventure and novelty seeking go hand-in-hand. The implication is that some people travel outside their usual places of residence because they want to experience daring and unusual moments. For instance, for the allocentrics and individual mass tourists, thrill seeking forms part of making destination choices and contributes to their experience and satisfaction thereof (Callender & Page, 2003; Bigne, Sanchez & Andreu 2009). This observation perhaps explains why adventure travels are gaining popularity. The finding that tourist motivation has a material bearing on their level of satisfaction in the north of Ghana is in line with a previous study by San Martin and Rodriguez (2008) who hold that travel motivation has an influence on tourist satisfaction at a destination. The study pointed out that culture, social contact and the destination’s attractions are the predictors of tourist satisfaction in northern Ghana. Culture perhaps, manifested as one of the major predictors of tourist satisfaction due to the authentic nature of the tangible and intangible manifestations of the region’s culture. Unlike southern Ghana which is somewhat culturally close to western cultures due to early and continuous European contacts, the north remains quite immune. Since culture appeared as one of the major push factors to the destination, and given that there is a cultural disparity or distance between the generating and destination regions, the culture of northern Ghana may appear unique and attractive to these tourists thus contributing to their overall satisfaction with it (William, 1998). Closely related to the issue of culture was ‘social contact’ which the study observed to have made significant influence on international tourists’ satisfaction on northern Ghana. Given that the quest for making new friends, and home-stay were the two (2) main compelling forces for tourists under the construct, it stands to reason that perhaps, tourist had the opportunity to interact and made friends who were welcoming and exciting. Secondly, the opportunity of home-stay probably allowed them to observe and enjoy the convivial and hospitable warmth of the people at close distance. This is even more satisfying since the Ghanaian hospitality in general is not a performed one but inherent. Cater (2002) states that tourists in search for interpersonal relationship with local folk benefit when the local people are welcoming. Gunn (1972) maintains that without attractions there is no tourism, thus despite the varied motivations to travel, they are dependent on the destination’s attractions. Consequently, the significant value returned as a predictor of the tourists’ satisfaction in the region suggests that the offerings of a destination have considerable influence in determining tourist satisfaction. Fridgen (1996) avers that the uniqueness, quality and authenticity of attractions determine activity participation of tourists and the fulfilment thereafter. On the contrary, it was observed that novelty/adventure did not have any significant influence on tourists overall satisfaction at the destination as opposed to studies by Lee and Pearce (2002) and Pearce and Lee (2005) who noted that novelty has a significant relationship with tourists’ satisfaction. Conceivably, unlike the motivation for destination’s attractions, culture and social contacts, tourists expectations might not have been met as far as novelty/adventure seeking was concerned. According to Fluker and Turner (2000), motivations stem from the urge to fulfil certain needs, and that participants have expectations of the services designed to satisfy those needs. Chi and Qu (2008) and Santouridis and Trivellas (2010) observed that overall satisfaction on travel experience is a major antecedent of revisit intention. In a similar vein, this study observed a positive bearing of tourist satisfaction on their revisit intention. As indicated in the study, more than two-thirds of international tourists’ revisit intentions to northern Ghana were predicted by their overall satisfaction. This finding is consistent with the Yoon and Uysal’s (2005) model which served as the conceptual basis for the study. (Parasuraman, Zeithaml & Berry, 1994; Santouridis & Trivellas, 2010). The model establishes that tourists’ are willing to go back to a particular destination, if they feel satisfied. This evidence denotes that if tourists are fulfilled with their travel experience at a destination, they would be prepared to make a return visit to where they received such experience (Oliver, 2010; Chen & Tsai, 2008).

6. Conclusions and Implications

- In theory, this study has contributed to literature by highlighting the motivations of tourists visiting northern Ghana, which previous studies have largely overlooked. The usefulness of the destination loyalty model by Yoon and Uysal (2005) has also been validated, especially in a developing destination, one with different destination attributes compared to Northern Cyprus, Mediterranean region (where the original model was developed). Following from that it is concluded that cultural experience, destination attractions, social contact and adventure/novelty are the factors motivating tourists to visit northern Ghana. These factors support the model by Dann (1977) and Yoon and Usysal (2005), which explains tourist motivation to travel being a function of push and pulls factors. Therefore, it is essential that destination managers in Ghana and other operators like tour operators and travel agents in the country take into consideration these dimensions in the quest to marketing northern Ghana. Particularly, the Northern Regional Office of the GTA could leverage the ecological and cultural heritage of the three northern regions, so as to help increase arrivals to Ghana as a destination. However, in exploiting such cultural heritage, it should be done with caution as this may result in the commoditization of culture or staged authenticity (King, Pizam & Milman, 1997), which can affect the originality of cultural attributes.It is also worth adding that since social contact is one of those factors that influenced the visitors’ satisfaction, it is important that the home-stay market be leveraged to the fullest in order to provide the basic stay services to tourists while granting them the opportunity to connect with the locals in their homes. This, if properly harnessed, could extricate local communities from poverty while promoting cross-cultural exchanges between tourists and hosts. Nevertheless, the issue of social contact has the potentiality of opening up the region, particularly the visited communities to issues of adverse acculturation and demonstration effect. Therefore, in doing this, the GTA should educate the local folks on the potential costs and benefits of tourism, likewise orientate tourists with regard to appropriate actions at the destination.Even though the study observed that tourists who travel to the destination are in need of adventure-novelty related activities, such visitors are seen as “high expectant guest”. Any efforts at attracting and satisfying them require discovery of unique tourism resources as well as development of new ones that would impact positively on their experiences. Arguably, such category of tourists is likely to be inherently disloyal, given that ‘unusualness’ is their dominant motive. Moreover, the study resolves that satisfied tourists are more likely to revisit, it is therefore imperative for service providers in whatever capacity, to ensure that tourists are satisfied with services rendered to them so as to generate repeat visits. This requires effective destination management. The GTA which has the mandate of ensuring quality in the industry should ensure that industry practitioners uphold basic service standards that would contribute positively to visitors’ experience of the destination.

7. Limitations and Future Research

- Factors, such as respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics and travel experience could shape the relationship among tourist motivation, satisfaction and revisit intentions, but these factors were not taken into consideration. Perhaps, better and more reliable results could have been unearthed incorporating the above issues. Therefore, a future study could measure how socio-demographic characteristics and travel experience affect satisfaction.Further, it would be quite interesting for future studies to also incorporate other motivational theories in testing the utility of the destination loyalty model, instead of the conventional push-pull model, which though relevant to this study, has been widely tested.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML