-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Tourism Management

p-ISSN: 2326-0637 e-ISSN: 2326-0645

2013; 2(2): 47-54

doi:10.5923/j.tourism.20130202.03

Appropriateness of Branding as a Tourism Resuscitation Tool for Zimbabwe

Mirimi Kumbirai1, Utete Beaven2, Mapingure Charity3, Mumbengegwi Patricia3, Kabote Forbes3

1Department of Travel and Recreation, Chinhoyi University of Technology, Zimbabwe. Private Bag 7724, Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe

2Department of Wildlife and Safari Management. Chinhoyi University of Technology, Zimbabwe

3Department of Hospitality and Tourism. Chinhoyi University of Technology, Zimbabwe

Correspondence to: Mirimi Kumbirai, Department of Travel and Recreation, Chinhoyi University of Technology, Zimbabwe. Private Bag 7724, Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

We investigated the appropriateness of branding in resuscitating tourism in a market facing a decline in tourist arrivals since the past decade that experienced macro-economic and political challenges. However the new political dispensation ushered by the Government of National Unity (GNU) created stable conditions allowing the Zimbabwe tourism sector to (re) brand. This saw the country then launching a new tourism brand, “Zimbabwe: A world of wonders”. The main purpose of this study was to explore the potential of previously unbranded tourist attractions to strength an ailing national brand facing a plethora of challenges. Our approach was based on a hybridised quantitative and qualitative dimension. Results indicate that branding strategies and policies in place to position Zimbabwe as a prime tourist destination employed by the tourism authorities in Zimbabwe are somewhat ineffective potentially due to limited stakeholder engagement. The conclusions thereof emphasise on the need to promote undiscovered tourist gems and foster an integrated destination promotion strategy that takes cognisance of stakeholders as a drive to improve Zimbabwe’s brand identity.

Keywords: Destination, Image, Branding, Undiscovered Gems, Resuscitation

Cite this paper: Mirimi Kumbirai, Utete Beaven, Mapingure Charity, Mumbengegwi Patricia, Kabote Forbes, Appropriateness of Branding as a Tourism Resuscitation Tool for Zimbabwe, American Journal of Tourism Management, Vol. 2 No. 2, 2013, pp. 47-54. doi: 10.5923/j.tourism.20130202.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- There is a decline in tourist arrivals in Zimbabwe as a result of covariance of a plethora of crosscutting issues[1]. The Ministry of Hospitality and Tourism Industry, spearheaded by the Zimbabwe Tourism Authority (ZTA) is pursuing an intense branding campaign with a new image launched in March 2011 (Zimbabwe: A world of wonders). Recently this has seen the tourism trend shifting with a steady increase in tourist arrivals[2]. Part of the blame on the decline of tourist arrivals has been laid on the shoulders of the relevant tourism authorities[3]. The main point of blame is that there is a lack of marketing of previously unexplored tourist attractions which are referred to as ‘undiscovered tourist gems’[4] and an overreliance on traditional destinations which target repeat visitors[5]. The concern is over the packaging of Zimbabwe’s undiscovered gems as a way of establishing a new tourism appeal for the country, with the Zimbabwe Tourism Authority (ZTA) accused of not convincingly packaging the country to its full tourism potential in line with contemporary tourist demand. This study was based on the premise that there are a number of off beaten track tourist resources (gems) in Zimbabwe that are unspoilt, untouched and virtually unexplored[6], whose potential contributions to the tourist volumes have not been explored.Our study was anchored on the notion that destination branding is a critical issue in tourism destination strategy and planning[7]. However, research elsewhere argue that putting destination branding into practice is no easy task and destinations face a number of challenges which have the potential to derail the best branding initiatives[8]. It has been observed that many tourists arriving in Zimbabwe show lack of knowledge pertaining to off the beaten track tourist resources (gems) that are beautifully cascading, breathtaking and fascinating, encompassing wildlife, scenery and culture [1]. There are concerns from various media that the country’s tourism brand (appeal) is no longer keeping pace with time in a highly volatile and unpredictable operating environment which has prompted this research on the packaging of the country’s not so common gems as a way of trying to salvage the country’s tourism. The objective of this research was to determine factors that dampen the success of destination branding strategies and outline Zimbabwe’s undiscovered gems and how they could be fully utilised for tourism development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Branding

- According to[9] branding is the act of impressing a product, service, or business on the mind of a customer or set of customers. This definition reveals branding as a process not a once off event and is applied to anything that organisations, people want customers to notice. Thus it calls for continuous review, update and implementation. In another view, branding is not only imposing the created image; the consumers also influence the brand through their perceptions[10]. Thus the branding process aims to make sure customers perceive the product or service as desired by the company, basing the branding strategy on real facts and product strengths. Looking at Zimbabwe as a destination, destination branding therefore becomes an important component in positioning the country as a prime tourist destination. According to[11] destination branding is:-“the set of marketing activities that (1) support the creation of a name, symbol, logo, word mark or other graphic that readily identifies and differentiates a destination; that (2) consistently convey the expectation of a memorable travel experience that is uniquely associated with the destination; that (3) serve to consolidate and reinforce the emotional connection between the visitor and the destination; and that (4) reduce consumer search costs and perceived risk. Collectively, these activities serve to create a destination image that positively influences consumer destination choice.”Another definition by[10] of destination branding is:-“an organizing principle that involves orchestrating the messages and experiences associated with the place to ensure that they are distinctive, compelling, memorable and rewarding as possible. Successful destinations brands resides in the customers heart and mind, clearly differentiate themselves, deliver on a valued promise and simply customer choices”The two definitions point to the same critical aspects, creation of a positive image in the mind of the traveller with a promise for high value for money that last for longer in the customer’s hearts and minds. In a bid to create that destination brand, destinations have a number of options. Destinations can be branded purely as tourism destinations without looking at other sectors of the economy. However[12] who carried out a qualitative study on branding umbrellas in Denmark concluded that cooperation in branding especially in overlapping target areas can bring positive results. [13] did a quantitative study on measure of brand orientation in the context of destination branding and examines its relationship to brand performance and brand leadership by senior management. Using data from destination marketing organizations he concluded that brand orientation consists of five dimensions – brand culture, departmental coordination, brand communication, stakeholder partnership, and brand reality – and has a strong, positive impact on brand performance. The findings also suggest that leadership by senior management is an important determinant of destination brand orientation. The results show that branding without a clear orientation leads to confusion among stakeholders and is not ideal for the industry. In a qualitative study by[14] on nation branding carried out in India, it was concluded that it was difficult to represent vast and diverse populations. This study informs the value of diversity in coming up with a brand. Thus earlier work by [15] placed emphasis on identification of the brand’s values and their translation into suitably emotionally appealing personalities and the target and efficient delivery of that message. The views of these two groups of authors place at the fore the need to cover all the essential elements that makes a brand despite the magnitude of the differences in key aspects of tourism in a particular destination.In their study[11] concluded that a destination brand should sufficiently cover image, recognition, differentiation, consistency, brand message, emotional response, and create expectations in the mind of the target market. It is upon this background that the Zimbabwean national tourism brand is being examined in the eyes of the tourism stakeholders.

2.2. Stakeholders in Destination Branding

- The stakeholder perspective is, however, under theorised in branding discussion as a whole[16]. According to[17], a corporate brand needs to deal with the requirements of multiple stakeholders especially in developing a successful brand. First and foremost a brand has to be created for instance a qualitative study was conducted in Turkey on marketing of Turkey as a Tourism destination.[18] argued that centralisation of destination marketing inhibits destination growth as it favours developed destinations at the expense of developing destinations. This problem they suggested could be resolved by embracing local authorities and other stakeholders in developing destinations. These views highlight the significant part played by stakeholders in developing a destination. However it does not give details on how and the extent to which the stakeholders can be involved in destination development particularly in branding. [19] conducted a qualitative study on destination brand identity, values and community in Australia. They concluded that destination branding requires a holistic approach which is reflective of the multiplicity of the values that constitute destination places.[19] findings reinforce earlier work by[18] and[20] that branding is not an end but a continuous socially constructed process that accounts for local destination characteristics. In his study[18] emphasised destination values and characteristics as key considerations in destination branding. Whilst this study was significant in informing the branding process, the identified values and characteristics where not subject to scientific testing. Thus quantitative studies to test the applicability of the values and characteristics in branding a destination are necessary.Destination branding is traditionally a top down approach that starts with National Tourism Organisations,[21]. Using qualitative methodology in Finland on Brand recovery: a quick fix model for brand structure collapse,[21] argues that without proper stakeholder participation destination branding can create a brand that generates too high tourists expectations from a destination compared to what the destination can offer on the ground. This results in unsatisfied customers. Unsatisfied customers are not good for both destination marketing organisation and destination stakeholders as it limits repeat business and ability to convince future clients of your products and services. These results are in line with results from[22] who conducted a quantitative study on effects of communication on tourists’ hotels reservation process and concluded that there is strong relationship between marketing and hotel reservations. Thus a holistic approach is ideal in trying to create a realistic brand that is appealing to the clients and can be satisfied by the stakeholders on the ground when the tourists visit the destination.Most tourism policies are developed by the central government,[21]. However when it comes to implementation, there are a lot of stakeholders involved. In a qualitative study by[23] on tourism policy and destination marketing in South Africa concluded that a positive chain of influence in which destination is portrayed in synergy with the tourism policy and objectives leads to sustainable tourism development. Although the study looked at stakeholders and policy developers other key issues on religion and culture are not tackled yet they determine the willingness of stakeholders to participate in tourism.In a quantitative study carried out in Hawaii on role of residents in branding tourism destinations by[24], it was concluded that destination marketing organizations and tourism service providers should understand the importance of the internal branding processes among residents, and should incorporate them into their destination branding strategy. These results emphasize the importance of community ownership of the branding process and the brand. However in Zimbabwe no study has been done to look at the extent of involvement of stakeholders (whether players or community members) in the branding process.[25] carried out a qualitative study on ministers statements on policy implementation and sustainable tourism development in Turkey. It was concluded that tourism ministers statements were economically and growth oriented. As key stakeholders representing the Government and arguing for or against investing in tourism it is imperative that they be taken serious in branding a destination as politic and destinations are inseparable,[26].

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sampling Techniques

- Purposive sampling was mainly used for flexibility in collecting data and also to eliminate unnecessary data. The technique gives space to identify important stakeholders in the research. Stratified random sampling technique was also used for the following reasons: to ensure that the sample will not have by any chance undue proportion of one unit in it. The population was too big and therefore had to be divided into strata according to operations and then the sample was picked randomly from each type of operation, that is, tourism business. Since the population included the whole of Zimbabwe we took the ZTA database of all tourism operators. Each category of the operators was the strata, e.g. tour operator, safari operator etc. From the strata we selected the most suitable respondents in line with the research objectives. Tourists were selected using a simple random sampling method from main tourist destinations in Zimbabwe.

3.2. Research Design

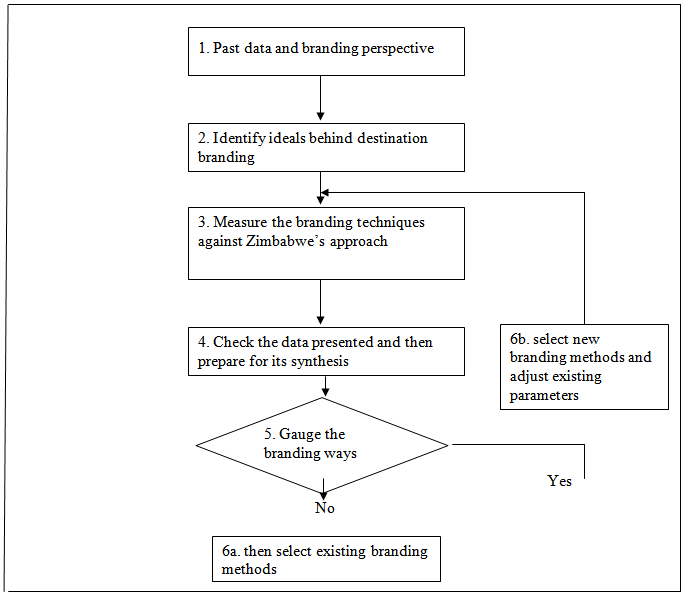

- A descriptive research design was used in conducting the research study in order to get cemented stakeholders’ perceptions and expectations. Investigations were carried out, at the offices of the Zimbabwe Tourism Authority. We used questionnaires in obtaining information from the ZTA departments and various tourism players. Personal interviews were carried out to obtain information from ZTA and stakeholders. Questionnaires were tailor made to cater for different stakeholders as a way to obtain more reliable, accurate and realistic information. All questionnaires were written in English. The study sample comprised of 45 respondents drawn from destination promoting companies e.g. Hospitality Association of Zimbabwe (HAZ) marketing personnel, Association of Zimbabwe Travel Agents (AZTA), the Ministry of Hospitality and Tourism and the National Parks not leaving out Zimbabwe Tourism Authority (ZTA) marketing personnel. This was mainly because these are the organizations directly involved with the tourists or tourism business in Zimbabwe. Of much importance is that these organizations are the ones which can recommend whether ZTA has been successful in branding the country. 90 international tourists also participated in the study since they are the ones who have an experience of Zimbabwe’s brand product.The progressive approach was taken beginning with simpler ideals and then moving in evolutionary fashion towards more elaborate models that more clearly reflect the complexity of destination branding. Presentation of data, identification of branding techniques and analysis enabled the best branding system to be chosen through various sampling procedures and synthesis. Model building procedures according to[8], as highlighted in the previous chapter were adopted to come up with the research framework. The branding systems were developed typically for Zimbabwe. The analysis was carried out following the approach illustrated in the figure below:

| Figure 1. Flow chart of the research framework adopted for branding survey adapted from[8] |

3.3. Data Analysis

- One way ANOVA was used to test the strength of differences in perceptions towards Zimbabwe as a tourist destination. Data was analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPPS) version 16 and graphs were done using the Sigma Plot and MS Excel 2007 version, and related using correlational tests to the literature review, and journals used in the study together with other studies elsewhere.

3.4. Limitations of the Study

- The first limitation deals with the representation of the research. In the study, samples were drawn only from two cities in Zimbabwe (i.e. Harare and Victoria Falls). If a diversified sample were drawn from different parts of Zimbabwe, then it would be more representative and more reflective of the country’s branding activities and practices.A total of forty-five respondents were analysed across the identified stakeholder categories as well as ninety tourists and at this point there were a number of findings that could be seen to be repeated and replicated across stakeholder categories and branding practices. As discussed, the stakeholder categories were devised as a means of identifying those most engaged with tourism branding in Zimbabwe. There was however a great deal of blurring across stakeholder categories and multi-membership of these. It should be emphasised that because of the individuality of the stakeholder informants in many cases it was not possible to see findings replicated in terms of their precise types of existing branding practices.

4. Results

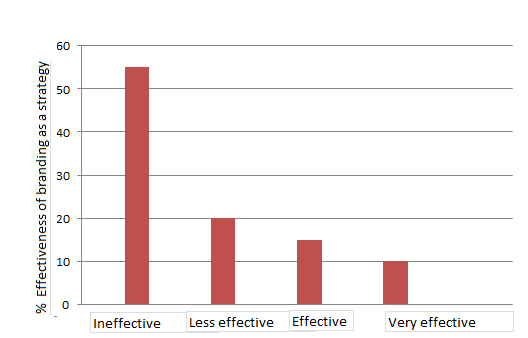

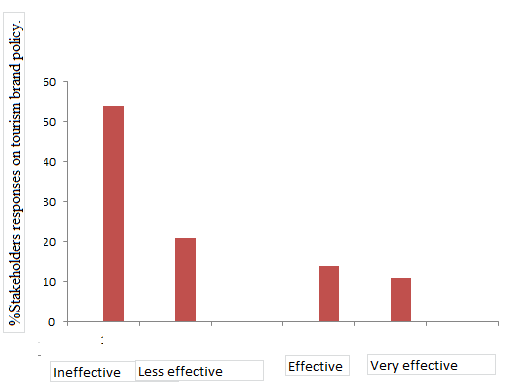

- A large proportion (65%) of tourists sampled in this research no longer see Zimbabwe as one of their premier tourist destination in Africa, only 35% of foreign visitors still consider Zimbabwe as their top choice international destination. There was a significant difference (ANOVA; p < 0.05) on the perceptions of foreign visitors on the performance of Zimbabwe as a tourist destination relative to regional competitors. We found that 75% of respondents view Zimbabwe as a below average or poor destination. Respondents mentioned that they are no longer fascinated by viewing Zimbabwe’s known tourist resources such as the Victoria Falls, Kariba and Hwange. To us this supports the notion that there are unbranded destinations in Zimbabwe that have the potential to attract recurrent tourists. There was a significant difference (ANOVA, p < 0.05) in the responses of the marketing personnel on their own evaluation of the implementation of a branding strategy and policy looking at its successfulness and whether there was a corporate branding strategy and policy in Zimbabwe. 55% of the respondents felt that there was no effective policy implementation on the branding of prime tourist destinations with a glaring ignorance of the potential of non-prime tourist destinations in boosting tourist arrivals (Figure 2). Our results show that a significant (ANOVA, p < 0.05) proportion of tourists view Zimbabwe’s current branding strategies in relation to tourist demand as ineffective (Figure 3). Zimbabwe’s position as a tourism brand is in a poor state because visitors are now expecting a new tourism dimension of which they say is lacking, prompting them not to continue visiting the country. Likewise there was a significant difference (ANOVA, p < 0.05) in perceptions of the effectiveness of branding strategies with majority of respondents (56%) blaming past problems on branding strategies by the ZTA that threatened Zimbabwe’s brand still affecting present branding. 20 % of the respondents think that there is no correlation between past branding problems and the current ineffectiveness of the country’s branding strategies. Measures that were put in place to manage and evaluate Zimbabwe’s tourism brand appear to significantly dissatisfy (ANOVA, p < 0.05) traditional Western tourists that come from America, Europe and Oceania who had a very low perception of the Zimbabwean brand. However, there was a significant satisfaction (ANOVA, p < 0.05) among African (65%) and Asian (68%) tourists. (Table 1).

|

| Figure 2. % response of tourism personnel on effectiveness of branding strategy |

| Figure 3. % Stakeholders responses on the development of a strong tourism brand policy |

5. Discussion and Implications

- Destination branding is a powerful tool for tourism providers to improve their appeal to consumer markets[4]. Branding a tourist destination, based on undiscovered national assets, is likely to create controllable expectations of potential inbound tourists, because then the touristic offer will be based on something that the country can offer. Confirmation of expectations, in turn, creates overall positive experience of inbound tourists (since most respondents mentioned that they are no longer fascinated by viewing Zimbabwe’s known tourist resources such as the Victoria Falls, Kariba and Hwange), which encourages repeated visits and word-of mouth[27]. Literature and examples from the tourism industry suggest that unpopular and/or unknown national history, culture and nature can be successfully used as tourist destination branding constructs. The present paper with the research purpose to explore the appropriateness of branding as a tourism resuscitation tool therefore proposes the use of undiscovered tourist gems for tourism destination branding in Zimbabwe. Recognition and effective communication of these unique features to potential tourists are seen as essential prerequisites for creating a distinctive tourist destination brand[12].The results of the survey suggest that national culture, history and nature can provide possible branding dimensions, which can be clearly associated with the tourist destination and upon which a tourist destination brand policy can be built[28]. A significant number of respondents felt that there was no effective policy implementation and a glaring ignorance of the potential of non-prime tourist destinations in boosting tourist arrivals. Peripheral locations can be seen as almost ideal cases to build the brands on the basis of culture, history, and nature due to their remoteness and relatively untouched and well-preserved assets associated with the named constructs. E.g., the BaTonga people, the Shangaai people, and farm tourism in the Eastern Highlands, Chimanimani area and Masvingo in terms of wildlife and Domboshava among others Eastern can be expected to build a stronger and more recognisable brand if effective policy based on branding dimensions of national culture and nature is formulated. In a bid to create a unique tourism destination brand, destinations have a number of options. Destinations can be branded purely as tourism destinations without looking at other sectors of the economy. However,[12] who carried out a qualitative study on branding umbrellas in Denmark concluded that cooperation in branding especially in overlapping target areas can bring positive results. In a related study,[13] did a quantitative study on the measure of brand orientation in the context of destination branding and examines its relationship to brand performance and brand leadership by senior management. Using data from destination marketing organizations he concluded that brand orientation consists of five dimensions – brand culture, departmental coordination, brand communication, stakeholder partnership, and brand reality – and has a strong, positive impact on brand performance. The results emphasise on stakeholder partnership an issue reiterated by a significant number of respondents. These results show that branding without a clear orientation leads to confusion among stakeholders and is not ideal for tourism development. In a qualitative study by[14] on nation branding carried out in India, it was concluded that it was difficult to represent vast and diverse populations. This study informs the value of diversity in coming up with a brand. Thus earlier work by[15] placed emphasis on identification of the brand’s values and their translation into suitably emotionally appealing personalities and the target and efficient delivery of that message. The views of these authors indicate the need to cover all the essential elements that makes a brand despite the magnitude of the differences in key aspects of tourism in a particular destination. In a study by[11] it was concluded that a destination brand should sufficiently cover image, recognition, differentiation, consistency, brand message, emotional response, and create expectations in the mind of the target market. It is upon this background that the Zimbabwean national tourism brand is being examined in line with promotion of unpopular tourist areas and fostering stakeholder partnerships.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The growth of Zimbabwe’s tourism brand has a plethora of benefits to the whole economy, thus its development is of utmost importance. There is need to concentrate on promoting unpopular and/or unknown tourist areas. The resolution of Zimbabwe’s tourism brand development lies in the promotion of the country’s somewhat unpopular tourist resources. The government should source foreign currency for the promotion of tourist resources that are not well known to tourists so as to be in line with the demands of the new international tourist. There is a need for a proper image analysis and environmental analysis where issues such as improvement of market perspective and confidence boosting of tourist players are done though proper government interventions. A candid environmental analysis that puts into perspective planning policies that needs to be looked at so that there is proper co-ordination between tourism planning and physical planning. Harmonisation of various pieces of legislation with the Tourism Act is needed to achieve an integrated approach towards the fulfillment of the destination’s strategic branding objectives.A review of the existing literature and findings from this study indicates that the image of Zimbabwe as a tourist destination is constantly being portrayed in relation to time-honoured tourist resources like Victoria Falls, Great Zimbabwe, Lake Kariba and Inyanga Mountains. Consequently, this has not been very helpful for the brand “Zimbabwe” in relation to attracting tourists and investors alike. However, a meticulous review of tourist resources in Zimbabwe reveals that the country has several tourism opportunities in various forms such as sports and adventure tourism, dark tourism; nature based tourism and cultural tourism but not adequately publicised. Therefore, there is a need to espouse these potentials by branding Zimbabwe such that these virtues would be widely communicated to the international tourist to enhance the brand equity of the country. Furthermore, the country’s ability to create brand awareness, unique competitive identity and customer loyalty is crucial in the competitive global tourism environment.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML