-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Tourism Management

2012; 1(2): 53-63

doi: 10.5923/j.tourism.20120102.04

Towards Integration of Rural Heritage in Rurban Landscapess. Case of Lithuanian Manor Residencies

Indre Grazuleviciute-Vileniske , Jurga Vitkuviene

Department of Architecture and Land Management, Kaunas University of Technology, Kaunas, 51367, Lithuania

Correspondence to: Indre Grazuleviciute-Vileniske , Department of Architecture and Land Management, Kaunas University of Technology, Kaunas, 51367, Lithuania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Due to rapid urban expansion the limits between the urban and rural areas became blurred and hardly distinguishable; Traditional rural environment is also changing rapidly from the social, economic, and cultural points of view at the beginning of the 21st century. These changes, although presenting numerous opportunities for increasing quality of life and economic prosperity, simultaneously cause threats to the authenticity and even survival of the valuable relics of rural landscape, such as rural settlements, farmsteads, individual buildings, and the residencies of manors. The focus of this research is the manor residencies of Lithuanian. Throughout the history manor residencies functioned in the agricultural and natural environment; currently part of them are being affected by the expanding urban areas. These changes urge to search for the new approaches to management of this particular heritage in order to preserve its valuable features and to adapt it to the needs of contemporary society, such as tourism, recreation, cultural and creative industries, urban farming etc. The aim of our research was to develop the interdisciplinary guidelines for management of the residential ensembles of manors absorbed by the urban expansion. The guidelines include the ideas for maintaining and strengthening the centrality of the manor residencies, preserving their integrity, restoring cultural continuity, and for functional and design innovations and management of heritage and social conflicts in the peri-urban areas with heritage features. The attention to finding the connections between this rural heritage in the changing urban context and the concept tourism was given as well. The methods of the research included the analysis of literature and photographical surveys of the manor residencies in the territory of the city of Kaunas in Lithuania.

Keywords: Urban Sprawl, Rurban Landscape, Manor Residence, Lithuania

Cite this paper: Indre Grazuleviciute-Vileniske , Jurga Vitkuviene , "Towards Integration of Rural Heritage in Rurban Landscapess. Case of Lithuanian Manor Residencies", American Journal of Tourism Management, Vol. 1 No. 2, 2012, pp. 53-63. doi: 10.5923/j.tourism.20120102.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Historic buildings and ensembles can be found not only in the centers of historic cities or towns but also at the fringe of constantly expanding urban areas. The rapid territorial expansion of urban areas creates a variety of new types of landscapes and both new heritage preservation and management problems and opportunities including the development of different branches of tourism. Different terms are used to describe these new landscapes: urban fringe, edge-cities, peri-urban, post-suburban, peri-urban interface, rurban, ruralurban etc.[1]. We use the terms rurban and rural-urban interface in order to underline the input and potential of rural environment to influence the character and functions of these new landscapes. We make the hypothesis that, if properly managed, the rural heritage in the rurban areas can be regarded as a resource for the development of the identity of newly urbanized areas as well as socioeconomic and sociocultural resource.Relevance of the research. In order to demonstrate the preservation problems and the potential of rural heritage in the rurban settings, we have selected the case of Lithuanian manor residencies. Suburban and rural estates, so-called manors, devoted to agricultural production, representation, and recreation were an inseparable part of historic landscapes of Europe and other continents. The manors were the particular feature of Central and Eastern Europe as well. Here the residential and management centers of the manors, so-called manor residencies, often were the prominent architectural ensembles with large gardens and played a role of cultural centers in the rural areas. Manors have maintained their economic, cultural, and even political influence until the beginning of the 20th century[2]. This is particularly true with the case of Lithuania the majority of the territory of which was incorporated into the Russian Empire until the beginning of the 20th century and serfdom here was abolished only in 1861. The present situation is radically different from many points of view. For example, the political, ideological, social, and economic shifts of the 20th century, including the policy of the Soviet regime, had caused the abolishment of the economics of the manors as a land management form, decline of the noble societies, and consequent severe decay of the manor residencies in the territory of Lithuania[2, 3]. Not only has the interruption in sociocultural and socioeconomic continuity and preservation problems justified the relevance of the subject of our research. The above mentioned urban expansion and formation of the transient rurban areas causing functional, environmental, sociocultural, economic, visual and other changes of the rural heritage are also important in this regard. Based on the research of M. R. Costa and D. Batista[4] we had distinguished two aspects of urban expansion affecting rural heritage:1) the integration of rural settlements previously located in the outer rings of cities through adaptations that naturally took place in the first stages of expansion of cities; 2) the advanced latter stage or urban-rural interactions, which in many cases have led to the loss of value of agricultural land, decay of rural settlements and buildings of heritage significance. In this stage “the antagonisms have developed between the urban and rural areas and the value of vernacular settings have played little role in urban metropolitan planning[4].”M. Antrop[5], G. Overbeek and I. Terluin[6] have noted the shift of focus of territory development towards the urban needs as well. According to G. Overbeek and I. Terluin “land use planning could act as a tool to deal with the various, often conflicting, demands for rural space. However, power imbalances among rural and urban municipalities, regional authorities, real estate planners, nature organizations and other stakeholders may hinder a proper use of this tool, usually in favor of urban claims on rural space.”Another aspect that has encouraged this analysis was the lack of the concept of the rurban tourism in literature and consequent limited attention to this subject in practice. Popular internet search engines do not give any search results for the terms rurban tourism or rural-urban tourism. Only several search results on the peri-urban tourism, mainly in the context of agritourism, were found. The valuable features of the manor residencies and other categories of rural heritage absorbed by the expanding cities encourage searching for the links between the rurban landscapes and the contemporary concept of tourism. Aim of the research. The complexity of the issues associated with the physical and social changes of the rural heritage resulting from the urban pressure and the peculiarities of the residencies of former manors of Central and Eastern Europe justify the aim of this article which was to formulate the interdisciplinary management recommendations for the manor residencies in the rural-urban interface based on the case of Lithuania. The development of management recommendations was based on the analysis of literature, several surveys on site in the territory of Kaunas city in Lithuania and on our previous researches including I. Grazuleviciute-Vileniske and J. Vitkuviene[7], I. Grazuleviciute-Vileniske et al.[2, 8, 11], J. Vitkuviene[9, 12], J Zilaityte[10].

2. Literature Review

- The review of literature had revealed the considerable interest in the topics related to the subject under analysis. For example, G. Adell[1] had presented the comprehensive review of literature on rural-urban interface and had reviewed the contributions to this field from the middle till the last decade of the 20th century. M. Antrop and V. Van Eetvelde[13], M. Fonseca et al.[14], G. Swensen[15], J. Vitkuviene[9, 12], M. Antrop[5, 16], G. B. Jerpasen and G. Swensen[17], J. Jureviciene[18], G. Overbeek ir I. Terluin[6], J. R. Miller et al.[19], R. I. Mcdonald et al.[20], J. S. Deng et al.[21], L. Azukaite[22], J. Bucas[23], M. R. Costa and D. Batista[4], L. Dringelis et al.[24], S. Gadal[25], D. Bardauskiene and M. Pakalnis[23] and many others had analyzed the global and local aspects of urban sprawl and urban-rural interactions. We have distinguished several trends of research relevant for the topic under the analysis.Metropolisation and sustainability. Transformation of the urban areas and their zones of influence that accelerated in the second half of the 20th century and the shifts in our understanding of the concept of development and the increasing environmental awareness are significant to our research. S. Gadal notes, “the transformation of the space into metropolised territories generates new forms of spatial organization. The metropolised territories are mostly often spatially multi-polarized urban discontinuities, segregated socially and functionally. <…> The metropolised territories are the geographic face of the globalization and the transformation of the human lifestyle”[25]. M. Antrop notes, “Thinking of urban places with their associated rural hinterland and spheres of influence has become complex. Clusters of urban places, their situation in a globalizing world and changing accessibility for fast transportation modes are some new factors that affect the change of traditional European cultural landscapes”[5]. He uses the term of functional urban regions to describe these massive changes and new kind of landscapes. Such complicated landscapes cannot be approached and managed without environmental awareness. S. Gadal[25] highlights the issue of sustainability in this field. He indicates that since the 1970’s two major processes transforming territorial, social and economic structures are the metropolisation and the emergence of the environmental problematic. Research on rural-urban interface, models of urbanization and suburbanization. In 1970 H. Lefebvre[27] had noted the lack of theory on urban problematic. He had developed the idea of simultaneous urban implosion and explosion meaning the increasing gravitational pull of cities and rapid suburbanization and spread of urban lifestyles. Contemporary researchers present numerous models of development of cities and rural-urban interface starting with the models of urban diffusion and industrial growth pole models[1, 5]. For example F. Indovina used the concept of diffuse cities as a model for recognizing and interpreting this new state of (dis-)organization and (de-)construction of built-up areas. He considered the process in Europe equivalent to the suburban sprawl in the United States[4]. Other more sophisticated models are based on accessibility of places and the transportation infrastructure. For example, M. Antrop sees urbanization as a complex process forming star-shaped spatial patterns determined by the physical conditions and accessibility and transforming rural and natural landscapes into urban and industrial ones[5].Guidelines for management of rural-urban interface. The analysis of the problems of rural heritage preservation under the pressures of urbanization usually is limited to the identification of the problems and presentation of the case studies; the analysis of literature had revealed only few management models. One category of such guidelines is the landscape assessment and management recommendations for particular areas prepared by different organizations and institutions. For example Guildford Landscape Character Assessment guidelines[28] include the classification of local rural-urban fringe areas and recommendations for their management. R. M. Olmo and S. F. Munoz[29] formulated landscape management guidelines for the peri-urban territory of La Huerta de Murcia in Spain. M. R. Costa and D. Batista[4] maintain the approach that heritage preservation in rural-urban interface must be considered at a landscape scale. “In order to facilitate the integration of peri-urban vernacular values in metropolitan contexts” they propose the urban development model based on heritage and landscape. The underlying idea is that urban planning and design must introduce the functional logic of rural and natural systems. They consider ecological and cultural structure of landscape as a significant basis to be manipulated and transformed through urbanization: “through integration into urban spaces, these structures acquire longevity and coherence. (This) <…>provides in the long term flexibility and stability to urban spaces and numerous benefits both to society and to nature. <…> different forms and functions both of the countryside and cities <…> promote inter-articulation and re-establishment of an urban-rural unity by connecting urban systems, ecosystems, and traditional agricultural systems to create a “new metropolis”. In this way, rural and natural spaces can be considered part of inherited cultural heritage, an indispensible element of urban systems”[4]. This is the closest equivalent to our study found in literature. Thus, we had made comparisons in the manuscript from the different points of view in order to show their common aspects and differences.Rural-urban tourism research. The developing area of rural-urban tourism research still remains the subject of secondary attention in the research of rural-urban interface. However, some useful experience in this field exists. G. Overbeek and I. Terluin[6] and C. J. A. Mitchell[30] had analysed the socioeconomic pressures resulting from urbanization and development of tourism on rural communities that strongly affect the local identity, which probably was the initial attraction of tourism interests. V. P. Carril V. P., N. Araujo Vila[31] argued for the need of academic research on the peri-urban tourism and had analysed a peri-urban tourist initiative based on the agritourism or “vegetable tourism” in the Baix Llobregat Agrarian Park in Catalonia. The project “Urban Agriculture + Peri-urban Tourism”[32] implemented in the surrounding areas of Casablanca in Morocco promotes peri-urban tourism as a means to diversify the economic activities of rural population; to encourage sustainable and participatory water management; to preserve peri-urban open spaces and natural areas; to promote sustainable agricultural production; to support the creation of ecological tourism infrastructure; to support sustainable urban-rural links. The properties of the manor residencies encourage integrating some aspects of tourism into their management guidelines.

3. Management Guidelines

- G. Swensen and G. B. Jerpasen[33] indicate that the analyses of rural-urban interface landscapes require interdisciplinary approach and one of the most obvious barriers in such interdisciplinary work is the lack of a common framework of understanding across a multitude of disciplines where different terminology and different methods are in use. They argue that the researchers from many different disciplines are involved in the landscape studies and this requires the use of integrative approaches. This justifies the development of the guidelines for management of residencies of former manors in the territory of rural-urban interface, which can be employed to coordinate the efforts in different fields. Based on Lithuanian experience, below we present several management ideas, which could form the framework for such guidelines.

3.1. Maintenance of Centrality and a Sense of Place

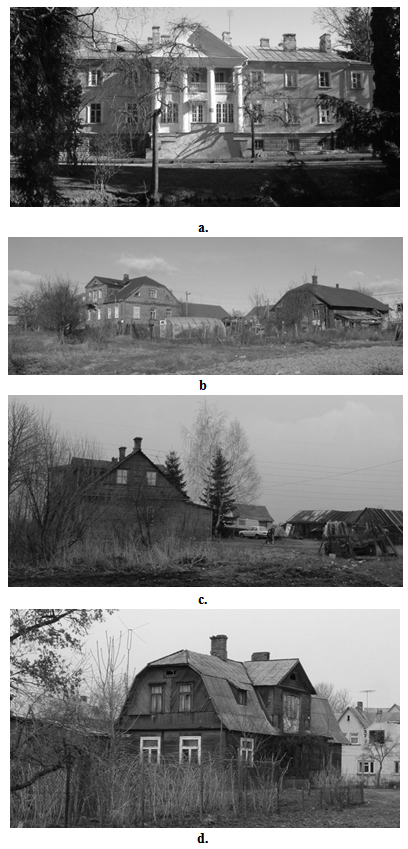

- Changing lifestyles, sociocultural attitudes and the economic system, increasing urbanization of the surroundings create the conditions to which the historic ensembles adapt with difficulties (fig. 1. b., c., d.). L. Azukaite[22] distinguished three generalized cases of how the built heritage of rural origination may act in such conditions: 1) culturally and socially significant heritage structures of considerable extent may attract the attention of institutions, society, and developers and may become the significant centers in new urban fabric; 2) the institutions and stakeholders may concentrate their attention to other object or project, such as the commercial center or infrastructural object, in the vicinity of the heritage object; 3) the development processes may be dispersed in the territory ignoring the heritage object and the patterns of the surrounding environment set by it. In two latter cases the probability of the harmonious integration of the heritage object into the new urban development strongly decreases.J. Vitkuviene[9] also notes that the preservation of the residencies of the manors strongly depends on what role they will play in the urban framework of the expanding city: whether the residence will become an integral part of new development or unwelcome obstacle. The residencies of former manors often consisting of at least several buildings and garden or parkland with water bodies and laden with historical and cultural values even if derelict are the ideal cases for the first scenario of concentration of social interests and processes. A good example of such ensemble is Aukstoji Freda manor residence serving as a seat of the botanical garden and recreation park (fig. 1. a.).

| Figure 1. Manor residencies of different cultural value and significance in the territory of Kaunas city (Lithuania): a. – Aukstoji Freda, b. – Sargenai, c. – Prendzeliava, d. - Kazliskiai |

3.2. Formation of the Rurban Structure

- According to M. R. Costa and D. Batista, a new culture of landscape implies that the more we are interested in urban spaces, the more we should be interested in rural and natural spaces[4]. This idea should be kept in mind analyzing the role of the manor residencies in the evolving rurban areas. In fact the issue of the spatial and visual dominance of the residence in the changing rural-urban interface is complicated and has no single solution. The residence is the primary element in landscape and based on this assumption new development should be coordinated according to the patterns set in landscape by it, such as the system of roads, landmarks, and green patches[9]. M. R. Costa and D. Batista also hold this view in their theoretical model of the urban development based on heritage and landscape: “urban morphology is inherently tied to the underlying support of the land, a fundamental factor in the creation of architecture and landscape”, “a heritage structure with cultural, economic, and ecological functions becomes in this way a central player in the (re-) organization and (re-) structuring of contemporary cities. It confers functional coherence and logic to the urban fabric, ecological and cultural integrity to the landscape mosaic, and visibility and utility to rural vernacular settlements”[4]. The example of Wilanow Town master plan for the suburb of Warsaw is the example, how the new residential development was accommodated to the historic road network set by the Royal Willanow residence. However, the visual dominance of the buildings and parkland of the residence, which was natural in the rural landscape, would be a challenge in the urbanized settings. As J. Vitkuviene notes, the emerging anthropogeneous elements in the background of the residence cannot be seen as absolutely negative from the aesthetic and heritage preservation points of view[9]. The subtle harmony between the historic and new development can add value to the territory. This feature can become a sign of the place, attract the attention of society and thus increase the potential for the rurban tourism. Harmonious coexistence of historic and contemporary architecture in the areas of rural-urban interface can create new aesthetic values, intrigue and stimulate cognitive interests. The challenge in this case is how to find the optimal visual relation between the object and new development preserving the visual integrity of the ensemble and observation possibilities simultaneously leaving the space for the development of new urban structures. The choice of the development strategy should be based on the cultural and visual significance of the residence and the value and legibility of the patterns set in landscape by it. The challenge is to find adequate links between the visual character of rurban places and their socially and ecologically sustainable spatial structure as M. R. Costa and D. Batista note[4]. J. Vitkuviene notes that the land-ownership was one of the fundamental features of historic manors[9]. The shifts in agriculture, economy, and society of the 20th century in the Central and Eastern European countries had caused the fragmentation of land-ownership and land-use in the surroundings of the manor ensembles. The landscape fragmentation in the rurban zones is evident in Western Europe as well. From one point of view certain forms of diversity are the favorable feature in rurban territories. However, the negatives aspects of diversity can be mentioned as well. For example, M. R. Costa and D. Batista note that the fragmentation of built areas and empty spaces leads to an overall complex territorial pattern, which is frequently modest in quality and in intensity[4]. This in part results in the unregulated chaotic physical, visual, and functional changes in the visual neighborhood of the manor residences absorbed by urban expansion. The consolidation of properties in the surroundings of the residencies is possible only in exceptional cases; however this provides excellent opportunities for visual centrality of the residence, urban farming, agritourism, development of recreational green areas and tourism infrastructure.

3.3. (Re-)Creating Integrity

- Historically one owner or steward managed the residential ensembles of the manors; consequently, restoring the integrity of the residence would be essential for its further existence and for maintaining centrality in new per-urban development. However, in many cases, after the subdivisions of the Soviet period and the successive privatizations, the actual legal integrity of the properties of the ensembles and the management by one owner cannot be achieved without the social discrimination and pushing out of the residents already living there. The injustice and social or functional uniformity should not be the goals of new peri-urban development. Integrated management of the ensemble through heritage regulations, planning documents, and non-governmental local initiatives can be a solution, when several or more owners manage the residence. The preservation means, such as conservation, restoration, renewal should be determined for the entire historic property after the comprehensive analysis of use and development possibilities, cultural and economic valuations, and the assessment of the social significance. As M. R. Costa and D. Batista note, in many cases the transformation or destruction of rural buildings within urban settings happens in the absence of a careful investigation of their heritage value[4]. The zoning of the ensemble can be carried out and different preservation regimes can be determined to each zone according to its values and authenticity. M. R. Costa and D. Batista note that the protection and rehabilitation of rural heritage in the urbanized contexts will only make sense when it is part of a wider strategy that considers, in detail, the factors and values of the overall cultural landscape[4]. Based on this consideration the integrated management of the entire network of residencies absorbed by the expanding city would be beneficial as well. For example, the expanding city of Kaunas (Lithuania) has gradually absorbed 16 or more residencies of different character and cultural significance[7]. As M. R. Costa and D. Batista note the process of integration of vernacular settlements into urban development will necessarily involve a systematic inventory of diverse kinds of heritage in which not only the “absolute” value of heritage properties but also their place in overall heritage on a regional urban level should be assessed[4]. As a result of such evaluation manor ensembles can be incorporated into larger protected areas, such as landscape reserves and can be assigned different preservation regulations and functions based on their values and development prospects. This would help to protect the residencies with the fragments of their authentic environment, to disseminate the information on the rurban heritage properties and to raise awareness and interests in society. The integrated management of the network of historic rural properties in the urban and rurban areas can help to develop optimal tourism infrastructure and stimulate rurban tourism through the development of the thematic cultural routes.

3.4. Restoring Continuity and Evolution

- Our previous researches on site have demonstrated that the historical continuity, the process of evolution of many manor residencies affected by the urban expansion is currently suspended; they have no permanent function or are completely abandoned[7, 10]. The main issue in the historical continuity and evolution of the residencies are the sustainable functions, which would not compromise the historical identity and distinctiveness of the ensemble and would correspond to the realities and the needs of the newly urbanized surroundings or the development plans. M. R. Costa and D. Batista[4] also underline the role of function in integration of vernacular settlements into urban development. They note that in the most cases the private uses of rural heritage, such as conversion of abandoned buildings into new residences, should be maintained; only in exceptional cases the conversion of this heritage for public use should be considered, making it a part of the network of contemporary city facilities[4]. The analysis of the links between the function and the physical state of the manor residencies in the territory of Kaunas city has demonstrated that the residencies with the functions close to the historical ones, such as recreational, administrative, residential, are much better preserved[7, 9]. The present owners and users of the manor residencies, whether the distant descendants of the noble families or completely unrelated with them, have no sufficient knowledge about the peculiarities of culture of manors. The interrupted historical continuity aggravates the search for new functions for manor residencies. They are usually adapted to recreation, residential functions, to the needs of museums, various kinds of amusement, accommodation, sites for conferences and events without looking back at the cultural and economic life and the recreation habits of the noble society of the past. However, considering the specific problem of interrupted cultural continuity and issues of desirable centrality and historical continuity, the new functions should not only sustain the physical state of the residence, but also reveal its cultural, economic potential, and contribute to the social cohesion. Residential centers of manors historically served for the multiplicity of interwoven and sometimes contrasting functions from traditional to most advanced agriculture, from manufacturing, technological innovations to cultural functions, recreation and representation. As Z. Medisauskiene[39] notes, the noble families of the 19th century not only sponsored the arts, accumulated rich libraries and collections of paintings, arms, archeological findings and other artifacts; the noblemen themselves composed music, wrote the plays for their amateur theaters, and translated works of literature. This historical knowledge can serve as a source of reference looking for qualitatively new but historically connected functions for the manor residencies in the completely different sociocultural, economic, and physical context. The manor residencies affected by the urban expansion, depending on their history and surrounding environment, can serve for the multiplicity of functions: ecological urban farming, cultural and creative industries, cultural tourism, agritourism, community and education centers, recreation etc. The multifunctionality of manor ensembles has historical roots and it should be favored in the rurban places often dominated by one or several functions.

3.5. Innovations and Adding Value

- The sustainable social, economic, functional, aesthetic and cultural innovations are essential for the further evolution of the heritage of manors the continuity of which was interrupted. More radical architectural, infrastructural, technical, gardening innovations can be introduced in the zones of lower cultural value or where the valuable historical features are completely lost. Even the contrasting architectural innovations can contribute to the integrity of the structure of the ensemble when new buildings are inserted in the places where the buildings of the manor historically existed but cannot be re-created because of the lack of data. Generally, the postmodernist attitude towards the design treating the tradition and the past as a source of inspiration but leaving the signs of its epoch at the same time would be welcome in such ensembles, where the integrity is the valued feature. Heritage preservationists usually recommend demolishing the Soviet insertions of low architectural quality in the manor ensembles. This would certainly contribute to restoring of the historical integrity. However, the period of the communist rule even if not favorable to the heritage of the manors, is a part of the history, which cannot be erased, and some well functioning insertions of that time can be left as a historical documentation and for public education. The innovations can be more freely applied in the less culturally significant manor residencies in order to make them more socially attractive and to add new values as well. Innovations are necessary for creating the favorable and attractive infrastructure for contemporary users and visitors, for interpreting and making rural heritage more accessible and legible for contemporary urban society.

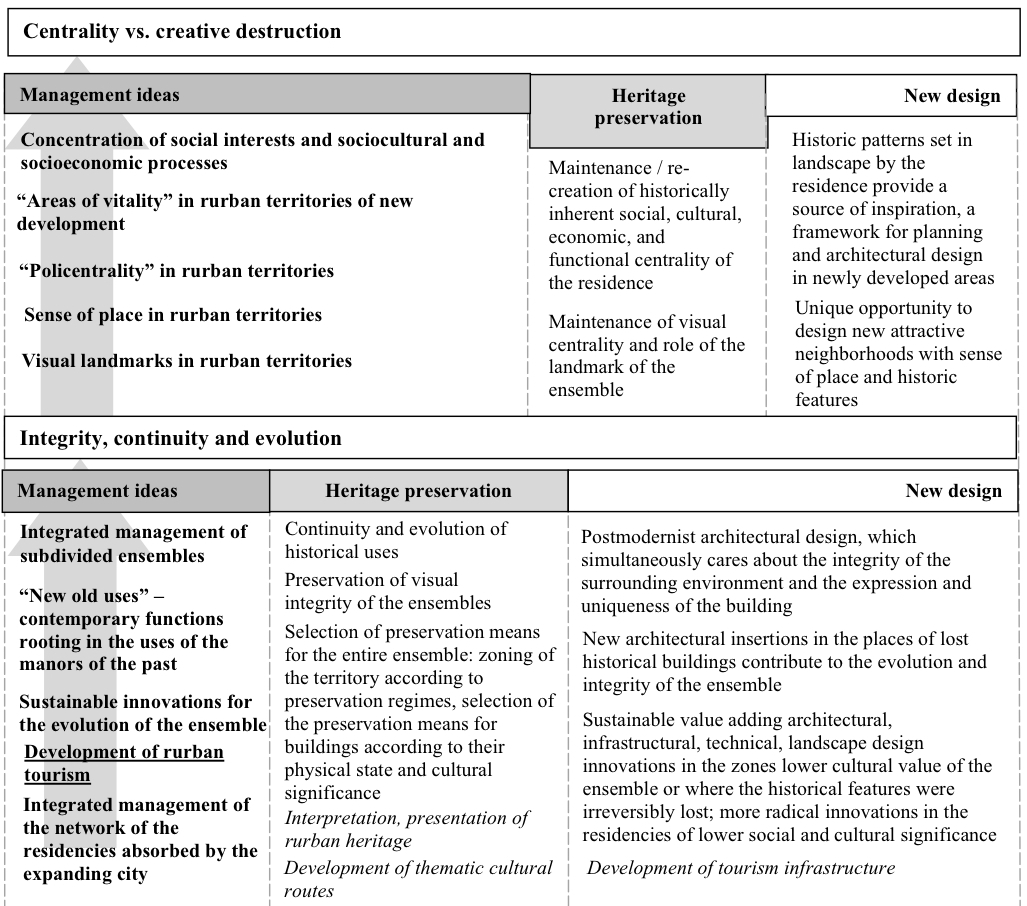

3.6. Development of rurban tourism

- V. P. Carril V. P., N. Araujo Vila[31] note that the analysis of tourism development is focused on four main types of tourism destinations and activities: urban tourism, rural tourism, costal tourism, and tourism in natural areas. However, the constantly expanding tourism industry is one of the leading sectors in the economy of the world. The researchers of various disciplines acknowledge that cultural heritage, including the built structures, plays very important role in the tourism industry[40]. This encourages considering the possibilities to adapt the rural heritage absorbed by the urban development to the needs of tourism. The manor residencies – building complexes with gardens or parks – hold the exceptional potential in this regard and can constitute a framework for tourism in rurban areas. However, the study by V. P. Carril V. P., N. Araujo Vila[31] showed that the individuals interested in peri-urban agritourism were not the mainstream tourists “that tend to show little interest in the agricultural nature of the area and who are content just to seek out leisure activities”, but rather the fully conscious persons aware of the peculiarities of the place and the importance of agriculture for it. The specific character of the rurban heritage in Lithuania including the modest architecture, rural aesthetics, connection to agriculture, do not allow to expect a massive flow of conventional tourists. Thus the development of tourism in the rurban areas should be oriented to specific braches of tourism, such as cultural tourism, thematic cultural routes, agritourism. Moreover, the literature demonstrates that cultural tourism can be equally economically beneficial as the tourism of other categories [41]. The researchers analyzing this phenomenon[42, 43] state that cultural tourists tend to stay longer in the place they visit; they use public transport and the services provided by the local residents; cultural tourists tend to travel alone or in small groups, they have much wider spectrum of interests and do not create congestion in the most popular sites. Moreover, individuals with higher income usually choose such way of traveling. This economic aspect is very important in rurban areas, where the development of tourism can stimulate policentrality, create new jobs and empower local population.The ideas on creating and maintaining the sociocultural centrality, formation of the rurban places, maintenance of integrity, (re-) creating continuity and evolution, stimulating rurban tourism and introducing innovations and adding value in the areas of rural-urban interface by using the heritage of the manors for the contemporary needs of society are summarized in the figures 2 and 3. The framework in this scheme encompasses the wide spectrum of interrelated issues ranging from the social problems and historic memory to planning and architectural design.

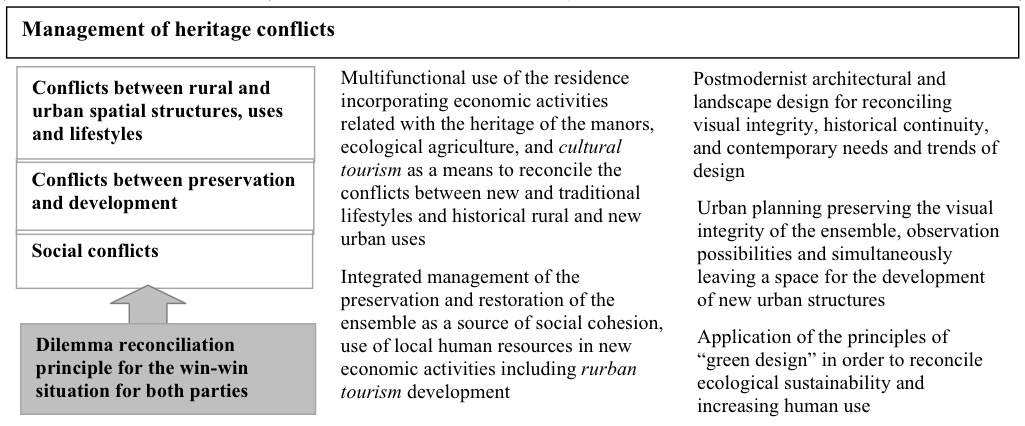

3.7. Conflict Management

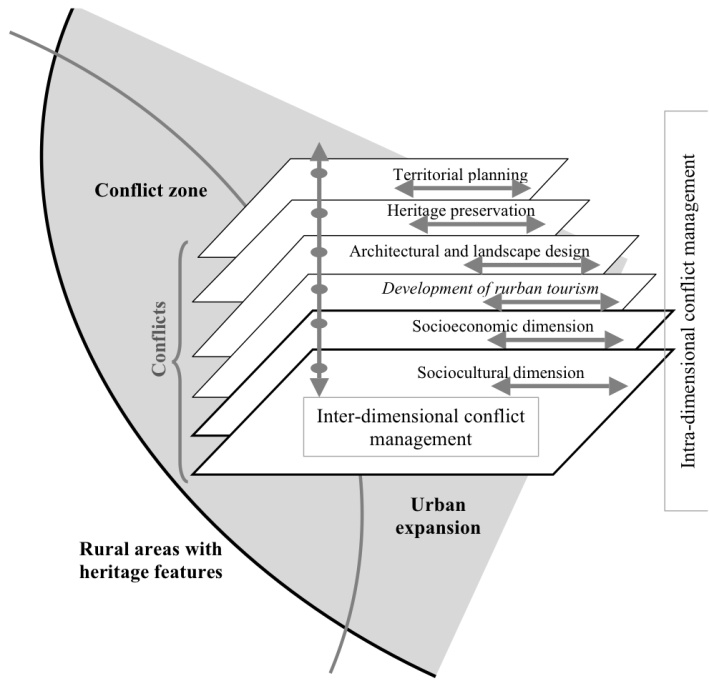

- The process of urbanization of rural territories with heritage significance inevitably produces numerous conflicts. Researchers acknowledge this conflicting nature of rural-urban interface often threatening preservation of built heritage: “Urban values and rural values tend to overlap confusingly, neither producing a feeling of being in the city nor in the countryside, and result in a profound crisis of identity in landscape”[4]. The analysis of literature, map surveys and analysis on site[2, 7 - 12] allowed summarizing the main conflicts occurring in the rural urban interface: the conflicts between rural and urban spatial structure and uses, the conflicts between the preservation initiatives and pressure for development, the conflicts of lifestyles and the above-mentioned social conflicts between old and new residents, the conflicts over the visual dominance in landscape of historic and new structures (Fig. 3). The zone where the unwisely regulated urban expansion clashes with the rural areas of historical significance may be identified as the conflict zone[22]. The attempts of the above-described integrated management of the ensembles, the selection of new functions, and the insertion of new architecture can produce the heritage conflicts as well.

| Figure 2. Hypothetical framework for management of the residencies of former manors in rurban areas[2, 9, 10, 22, 36] |

| Figure 3. Management of conflicts related to heritage in rurban areas[2, 22, 38, 39] |

| Figue 4. Management conflicts integrating the residencies of former manors into the urban development[2, 22, 38, 39] |

4. Conclusions

- In order to demonstrate the potential of the manor residencies in the development of rural-urban interface we have formulated several management ideas aimed at turning these abandoned or inappropriately used ensembles into the areas of social, cultural, and economic vitality in the peri-urban territories and into the generators of the sense of place, at the integrated management of the subdivided properties, searching for the contemporary functions rooting in the uses of the manors of the past, at sustainable innovations in and the evolution of the ensembles; our recommendations for heritage preservation include the maintenance of the role in landscape and the integrated selection of the preservation means and regimes; the ideas for new design in the territories of ensembles and in the surrounding territories including the creation of new neighborhoods with the sense of place, the postmodernist and “green” design; the ideas for development of the rurban tourism; the proposed management of heritage conflicts between the urban and rural spatial structures, uses and lifestyles, between the preservation and development, and management of social conflicts are based on the idea of dilemma reconciliation.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML