-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Tourism Management

2012; 1(1): 10-20

doi: 10.5923/j.tourism.20120101.02

Demographic Phenomena and Demand for Health Tourism Services Correlated in Poland

Adam R. Szromek 1, Małgorzata Januszewska 2, Piotr Romaniuk 3

1Department of Organization and Management, Silesian University of Technology, 41-800 Zabrze, Poland

2Department of Regional Economy and Tourism, Wrocław University of Economics, 53-345 Wrocław, Poland

3Department of Health Policy, Medical University of Silesia, 41-902 Bytom, Poland

Correspondence to: Adam R. Szromek , Department of Organization and Management, Silesian University of Technology, 41-800 Zabrze, Poland.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The changes in the demographic structure of societies are one of the key factors affecting the social and economic life in a modern world. The article tries to identify key demographic changes that affect the demand for health tourism services. It focuses particularly on the situation in Poland, as in this country the worst levels of basic demographic indicators in Europe has been recently observed. Authors utilize the yearly number of spa visitors coming to the Polish health resorts in period 1995-2009. The data were compared with the demographic trends referring to the number of population in 15 age categories, the probability of death, average life expectancy at birth, number of deaths and births per 1000 population. The impact of individual factors was examined by the analysis of correlation between the scale of demand for health tourism services, and the time series on demographic factors. The prediction for the further development of the phenomenon required the use of linear regression and multiple regression. In result of the performed analyses, it is concluded that demographic changes may be a key factor negatively affecting the number of patients coming to Polish spas, and the upward trend observable in recent years in terms of the demand for health tourism in Poland, with a great probability will turn into a downward trend in the forthcoming years.

Keywords: Demographic Changes, Spa Services, Health Tourism, Poland

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The changes in the demographic structure of societies are undoubtedly one of the key factors affecting the social and economic life and the phenomena appearing in these spheres in a modern world. It can even seem that the importance of this factor increases along with the progress of civilization. Changes in the demographic structure of societies also impact the phenomena observed on the tourism market. In case of the health tourism, such an influence may appear in a particularly strong manner.The article is an attempt to identify key demographic changes that affect the demand for health tourism services. For this purpose, ,authors decided to refer to the world most important demographic reports and try to apply the conclusions arising of them at the regional and national level. The paper focuses particularly on the situation in Poland, due to the fact that in this country in the last decade the worst levels of basic demographic indicators in Europe has been observed, i.e. the lowest fertility rate, the highest percentage of people aged 65 years and more, the highest level migration, etc.; see: World Tourism Organization and European Travel Commission 2010[1]. At the same time, strong traditions of the health tourism in connection with the medical spa, as well as favorable location of this country and its geopolitical availability, such as membership in the UE and Schengen area, make it an interesting and attractive touristic destination. We can therefore assume that in Poland the impact of demographic changes on the health tourism may be particularly sharply observed.

2. Background

2.1. The Demography in the World Scale

- As evidenced by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) report[1], the total world population between 2009 and 2030 is going to increase from 6.9 billion to 8.3 billion people. Nonetheless, this increase will not regularly spread throughout the world, since some regions will grow, and the other are going to experience a clear decline in population. In Europe, as it is estimated, the decline in population will be by 1%, while in the Americas and in Asia the population is going to increase by 17% and 18% respectively. Only in China and India the population increase is expected to reach 17.6%, 17.9% in the discussed period. Such a trend should not be surprising, since during the second half of the twentieth century there was a several times increase of the population in the Arab countries (e.g. in Egypt the twofold increase of the population was observed, in Jordan it increased nine times). At the same time in European countries the increase was relatively small, as for example in France it was 42%, and in Denmark only 23%[2].While a global perspective does not indicate significant implication in regard to the problem of the age structure of the population, we can run into significantly different conclusions if to analyze this question from regional perspective. In Europe the average age among populations is going to grow. The process of aging is already observable, but, as expected, in relatively short perspective. the average age of the European population will rapidly exceed 50 years, while during the same period the average inhabitant of Asia will be less than 45 years[1,3,4].Even before the referred UNWTO report, the European Union Member States, as well as the European Commission have published own reports on the demographic phenomena. The most important of these is the Report on the Aging Population prepared by the Directorate General for Economy and Finance of the European Commission and the Economic Policy Committee[5]. Assuming the long-term perspective of the forecasts, the report states that by 2060 the consequences of demographic change will affect all European countries, having negatively impacted the economies and social spheres. The report also points the expected growth of the number of people in age over 65 in Europe. While in 2008 this group accounted for 17% of the total population, in 2060 it is going to rise to 30%. Obviously, this is a measure of the average, and therefore in some countries the growth rate is going to be lower and higher in another ones, e.g. in Poland the share of population over 65 is going to increase from 17% in 2008 to 36% in 2060. The general picture of contemporary world demographic situation shows that the demographic change will affect particularly Europe, but it should be noted that such a view is shortsighted, and in reality the negative demographic phenomena in Europe will also have its consequences in other regions, by affecting the demand for tourist services, but also international trade and general economy.

2.2. The Essence of the Health Tourism

- Goodrich[6] and Goodrich[7] have defined health tourism as „the attempt on the part of a tourist facility or destination to attract tourists by deliberately promoting its healthcare services and facilities, in addition to its regular tourist amenities”. Some researchers provide much broader definition of the health tourism, as for example: „(...) each kind of journey, which makes a person to feel healthier”[8]. Provision of such a kind of service requires the employment of qualified medical personnel, maintenance of the diagnostic and therapeutic equipment, as well as a know-how relating to the food and nutrition, and traditional and modern medical techniques. The English Tourism Council[9] adapts the North American definition of health tourism, which describe it as products and services that are designed to encourage and enable their consumers to improve and maintain health by a leisure activities and education relating to distortions at work and at home.Bennett et al.[10] in turn, describe the following types of journey as health tourism:- pilgrimages to major rivers for physical and spiritual cleansing- traveling to warmer climates for health reasons- taking cruises which offer specific health treatments- government encouragement of the use of local medical services by international visitors in recent years- ‘thalassotherapy’ centers which offer warm sea-water treatments- ‘sanitourism’, which involves hospital centers catering not only for the ill, but also offering accommodation, stress reduction programs and the like to patients’ families- visiting a health resort for health-related activities or medical treatmentsIn summary, health tourism are trips and journeys outside the place of residence, which are aimed at improvement of the physical and mental health, preparation of the body to the increased physical and/or mental and intellectual activity, and at maintenance of the good physical and mental condition. Still this is somewhat limited way of defining the health tourism, particularly if to take into account a set of basic features of the stays connected with health tourism. These are[10]:- location (state or territory and remoteness),- menu (type of cuisine, e.g. vegan, organic),- health assessment (from blood pressure to nutritional appraisals),- lectures/workshops (classes provided),- tailor-made programs (customized approaches),- seminar/conference facilities,- length of stay,- ambiance (as manifested through the natural surroundings),- cost (e.g. bundled pricing).Undoubtedly the tourism activity related to prevention and health care is one of the types of tourism, where the impact of demographic change may be particularly strong. Biological processes occurring in the human body are impairing along with the age, and the ability to extend the time of their proper functioning depends on the method and frequency of stimulation. It seems therefore, that the health tourism as a form of touristic activity that uses the advantages of the natural environment, may be the optimal solution to many problems of the modern civilization. In result of the fact, that the efficiency of the human organism depends on the age, the health tourism is particularly popular among the elderly (65 years and more). It would seem therefore that the aging of populations can only improve the situation in sector of the health tourism services. Is that really true?The demand for the tourism services is affected by many different factors, such as economic, supply-side (i.e. tourism policy, transport infrastructure and accommodation, activities of the tour operators), but also socio-psychological, including the amount of free time, urbanization, motivation, and – last, but not least – demographic structure of the population and its dynamics. As already mentioned, the increasing number of older people should positively impact the demand on health tourism services. But it is not just about older people, as if to take into account the criteria for assessing the quality of human life (QOL). We can see among these: physical well-being, including wellness and recreation/leisure, health, nutrition, recreation, mobility, health care, health insurance, leisure, activities of daily living[11]. These features refer to people in each age, and consequently each age group can affect the popularity of the health tourism, although probably it will highest in the case of the elderly.The forms of health and tourism business are very diversified, as is often dependent on the role that the medical spa plays in the national health care system. In some countries, like Poland, Slovakia, and Romania, the health tourism coexist on an equal footing with other areas of medicine . In other countries, e.g. UK, Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark, this form of activity is not treated as medical treatment, but at most paramedical [12]. In countries where the medical tourism activity is associated with physical medicine, a health resort used to be the place of providing such practices. It is estimated that the global spa industry generates nearly U.S. $ 40 billion per year, with more than 25% of this amount obtained in spas in USA and Canada[13].

3. The Material and Methods

- To examine the impact of demographic changes on the demand for health tourism requires to adopt an assumption that relates to the research area. The scope of tourism activity associated with the practice of health tourism is so huge that its description by means of one variable is not possible. It was therefore decided to limit the study, and analyze the term involving the use of medical spa treatments. For this purpose a variable including the yearly number of spa visitors coming to the Polish health resorts has been used. The period of origin of the empirical data is years 1995-2009. The data obtained from the Eurostat (statistical office of the European Union) databases were compared with the demographic trends observable in Poland for the period 1995-2009, namely those referring to the number of population in 15 age categories, the probability of death, average life expectancy at birth, number of deaths and births per 1000 population. The study takes into account the division into the subpopulations of males and females, as groups with distinctly different demographic characteristics.Capturing the direction of long-term trends regarding the demographic phenomena is also required to examine long-term changes of the mentioned demographic characteristics. For this reason, some of the demographic factors are presented in annual terms for the years 1950-2009.The impact of individual factors was examined by the analysis of correlation between the scale of demand for health tourism services measured by the number of patients arriving to the Polish health resorts, and the time series on demographic factors, mainly the population in 15 age categories. In the analysis of cross correlation we used Pearson correlation coefficient, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient, Kendall's correlation coefficient. The proper measure has been selected depending on the distribution of characteristics. To examine the distribution of characteristics we used Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. The prediction for the further development of the phenomenon required the use of linear regression and multiple regression, which results are presented in the further parts of the paper.The activities of the Polish health resorts has been already described by Kapczyński and Szromek[14], who put forward two hypotheses concerning the development of health tourism in the Polish health resorts, and at the same time confirm the Tourism Area Life Cycle concept developed by Butler[15]. Hypotheses (the primary and the modified) assuming the further development of tourist activities in the Polish health resorts is consistent with the life cycle of the tourist area, but also take into account the transformation of spa product. Forecasts prepared for the health tourism however, resulted solely from the historical facts that confirmed the cyclicality of the development of touristic areas. The study of the impact of the demographic factor may confirm the fact of its influence on the number of patients arriving to health resorts, as a symptomatic variable imaging the development of health tourism.

4. Results

4.1. The Demography of Poland

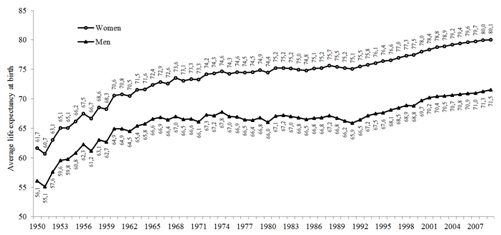

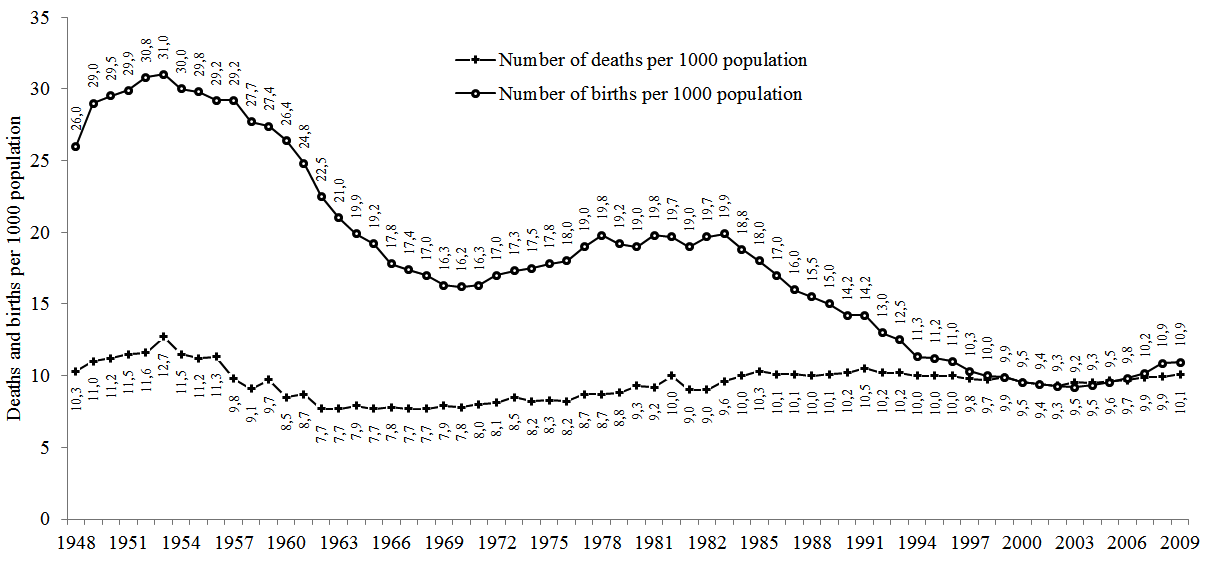

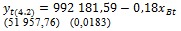

- When analyzing the socio-economic position of European countries it can be noted, that Poland occupies a special position as a post-communist country, which after two decades of economic transformation joins the group of developed countries. Along with this transformation also the demographic indicators are changing, particularly the fertility rate, which in 1950 was 3.6, and then began to decrease in subsequent years, to reach in 1989 a level of simple replacement of generations (2.1). Similar trend is noticeable in all countries during their economic development. In Poland it kept decreasing during the transformation period, and currently, although for few recent years has achieved an upward trend, is still among the lowest in Europe with the value of 1.27 children per woman. It seems therefore that the difficulties associated with the replacement of generations in Poland will deepen in future.As for the another indicator, as presented on the figure 1, we can observe a significant increase in the average life expectancy for both women and men since 1951 and 1990. Initially, namely in the years 1951-1960, the growth was very dynamic, as the average life expectancy has increased of about 10 years. Then the upward trend became relatively stable, although it was significantly higher in case of women, which resulted in a noticeable increase of the gap between the life expectancy of both sexes in the period 1961-1991. In case of women during the 30-years long period the life expectancy has increased of about 5 years, while in case of men it remained almost unchanged.

| Figure 1. The average life expectancy at birth in Poland |

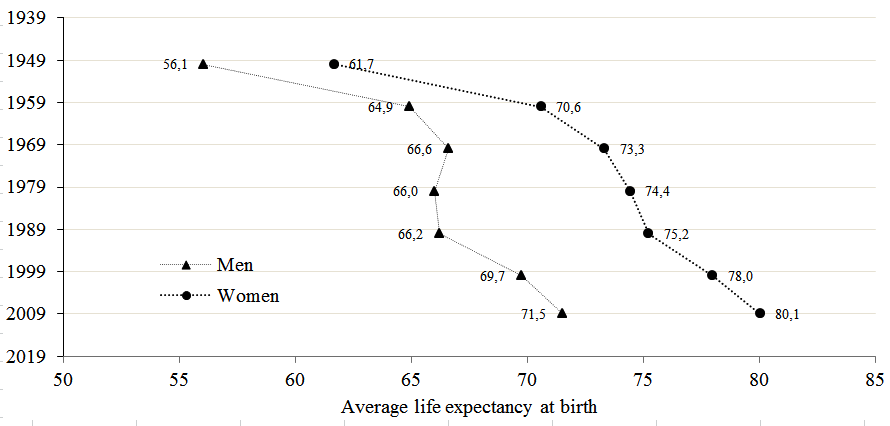

| Figure 2. The average life expectancy at birth in Poland in the years 1950-2009 |

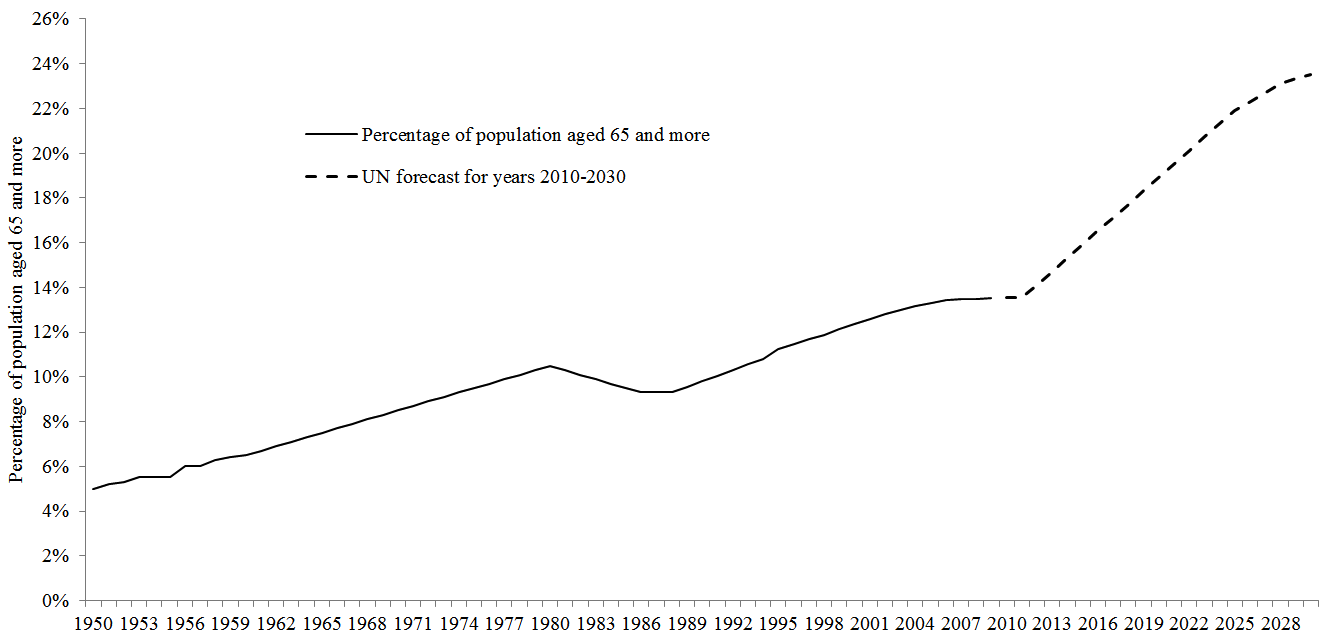

| Figure 3. Percentage of population aged 65 years or more in Poland |

| Figure 4. The ratio of deaths to the number of births per 1,000 people in Poland for |

4.2. The Impact of Demography on Health Tourism

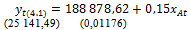

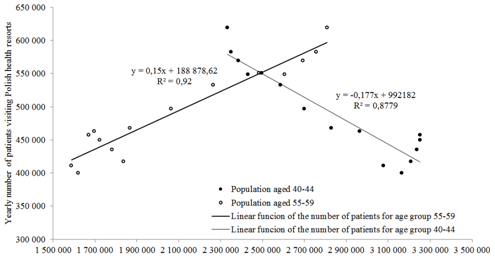

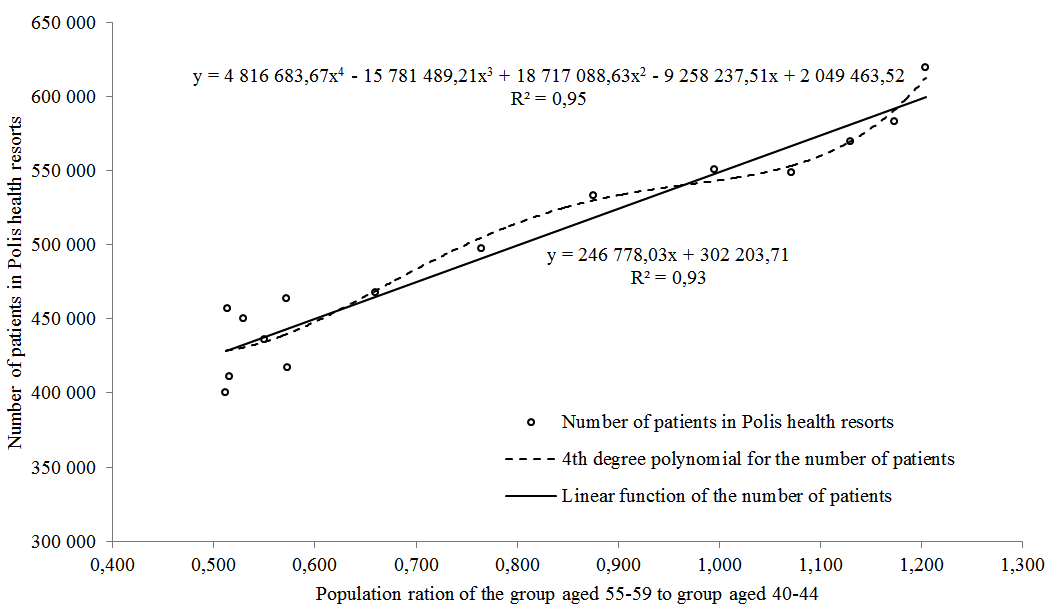

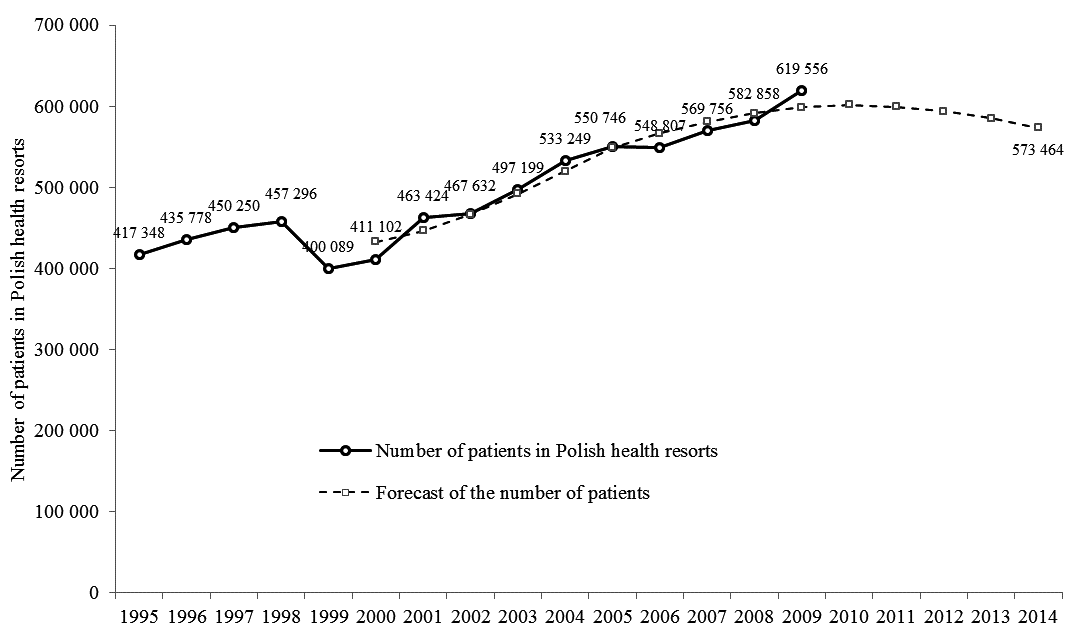

- The described above features of population in Poland were analyzed to identify the variables that are most important in explaining the number of spa visitors coming to the Polish spas for therapeutic purposes. We can note a strong correlation (increasing) between the number of spa visitors who have come to the Polish health resorts in the subsequent years in relation to the number of people aged 25-34 years, 50-59 years and 70 years or more (p<0.05). A strong negative dependence in turn is noticeable in the case of such age categories, as 19 years and less, 40-44 years and 65-69 years. The highest positive correlation is observed among people aged 55-59 years (r=0.93, p<0.05). In case of a category 65 years and more, a significant, but lower than in other cases, correlation was observed (r=0.87, p<0.05).Attempting to describe the observed dependences, parameters relating to four models describing the variability of the number of Polish patients were estimated. The models are based on two variables. The first is the number of people aged 55-59 years (the stimulant), and the second variable is the number of people aged 40-45 years (which is destimuli).The linear model (1) explaining the number of patients by the number of people aged 55-59 years shows a rising trend, which means that the increase in the number of people aged 55-59 years also implies an increase of patients (the error of the estimates of parameters D(ai), where i is the parameter number, is given in parentheses).On average, the increase of the number of population aged 55-59 years of about 100 people entails an increase of the number of patients by 15 people. However, in the case of model (2), the increase in population of people aged 40-44 years about 100 people involves a decrease in the number of bathers on average about 18 people. Both dependences are presented at the figure 6.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| Figure 5. Population structure by gender and age (in thous.) |

| Figure 6. The number of patients and the population in two age categories |

| Figure 7. The number of patients and a synthetic variable |

| Figure 8. Prediction of the number of patients in the Polish health resorts |

| (3) |

5. Discussion

- According to reports on the demographic changes occurring in recent years, we can conclude that the impact of these changes is significant especially in Europe. While the situation is slightly different in individual countries, it should be noted that there are several major factors that may affect the tourist activity of Europeans in forthcoming decades, Those factors are both of quantitative and qualitative nature. Namely they are:A. Decreasing fertility among European populationsReports[3][4] points the decline in the fertility rate in all European countries to a level below the natural replacement rate (2.1 children per woman). This means that while the world population continues to grow, in Europe it is expected the number of births will continue decreasing. This does not automatically mean that it will reduce the population, since increasing the average life expectancy of Europeans will allow the size to remain balanced (fewer people being born, but even fewer die).B. The increase in inequalities between age groups There is a growing prevalence of non-working age people in relation to people in working age, which progressively with each generation becomes more and more heavy burden for the economically active part of populations and reduces the financial capacity of European countries.C. The aging of populationsThe percentage of people aged 65 years and over in the general population is systematically growing, and thus the average age of Europeans increases. As a result, more and more people tend to be burdened with various diseases and costs of their treatment are also growing.D. Intensification of international migrationsThe consequences of differences between countries (including the level of income of workers performing the same jobs, unemployment rates, living standards and opportunities for intellectual development) force the residents of less developed countries to seek opportunities in migration. Since young people (under 30 years old) show the highest propensity to migrate, in their country of origin this may result in intensification of the effect of aging.Those four factors are widely reported in literature[18]. However, it seems that it is too narrow perspective for the analysis of impact of demographic changes on the contemporary socio-economic processes, including tourism, as some demographic phenomena also seem to interact indirectly. It is therefore proposed to expand the list of factors mentioned by several observations arising from both the already described phenomena, but also some more, which are only indirectly related to the demographic situation. Undoubtedly, an important factor influencing the demography of modern Europe are the transformations in family patterns. Roussel[19] describes several models of families observed in each group of European countries:Scandinavian countries - combines the "modern" model of marriage with "traditional" model of fertility. Characterized by the lowest intensity of entering the first marriage, the highest instability of marriage, and the procreation not associated with a formal relationship, but high fertility at the same time.Western countries – characterized by high instability of marriage and a high proportion of births outside marriage. The cohabitation exists mainly in premarital period. Fertility remains relatively high.“Center” countries - marriage is an unstable institution, but informal relationships are not as common as in the first two models. The proportion of births outside marriage and fertility are also on the lower level.Southern countries – the institution of marriage here has remained strong, but the number of births is decreasing. These countries are characterized by a "traditional" model of marriage and the "modern" model of fertility.Countries of Central and Eastern Europe – prior to 1989 there was the fertility rate was highest here, now it became the lowest (comparable with the Southern countries). Cohabitation in these countries is not an alternative, as the percentage of births outside marriage is low.The differences between these models are worth noting, as they can mean the diversity of ways to spend free time and recreate. Similarly the process of transformation of a family itself can be of substantial importance. A theory of fertility by Becker[20] indirectly confirm this, while inducing the relationship of behavior mechanisms with the level of education and so-called "Income effect" and "price effect". First of them means that people who are better educated, and also receive higher income, can afford the expensive goods much earlier than those, who are poorly educated and get lower incomes. Such goods are, in this case, marriage and children. People with higher education, not only are more involved in tourism, but also are more keen on providing the touristic services to family members. The “Price effect” means the existence of an alternative cost, which concerns the possibility of loss as a result of taking certain decisions. The time that individual "invests" in the family could be spent on touristic travels. Thus both effects affect the travel behavior.The migrations in turn, are a factor that should be applied to the geopolitical situation in the region. Post-communist countries are a good example of this, being negatively affected by this phenomenon for a half a century now. External migration of recent years are mostly economic in nature, and are associated with the EU labor market. However, although generally they are characterized by lack of rootedness in the destination, they affect the transformation of the tourism industry mainly throughout the development of foreign tourist air, road and sea transport, developing market of travel agencies, as well as improvement the standard of accommodation. Beside of that, migrations have also impact on touristic consumption, i.e.:- the increase in tourist trips to the destination countries (family trips, friends),- increase in arrivals of tourists from the destination countries to the countries of immigrants' origin (an effect of wider transport network),- changes in the local labor market and thus increase of income level, which result in increased expenditure on tourism and investments (i.e. in estates, as observed since 2006 in Romania and Bulgaria).It is also worth noting that the factor of increasing life expectancy used to be interpreted too narrowly. Longevity enhances the incidence of re-marriage by people who have grown children (as a consequence of divorce and widowing). In this case, the bond between the families of both newlyweds usually is shallow and superficial. Weak ties do not affect positively on the need for shared leisure activities, celebrate family events, etc., and therefore do not encourage temporary migration. Lack of relationship also affects the process of independent decision-making regarding tourist trips. Also the increasing economic independence of women causes the spouses not only traveling separately but have other motives to travel.Sagrera[21] draws attention to the positive side of aging. It is believed that from an economic point of view, the burden with the older population is not such a problem as burden with children, because seniors are getting healthier and better educated, and many of them could be professionally active, and certainly – they could also be active in tourism. Indeed, optimism in this regard seems to be justified. However, although this is not a factual argument to raise the retirement age, it is worth noting that many countries take into account such a solution. The reason is by no means the capacity to undertake economic activity, but the need resulting from the rising cost of insurance (pensions and health).We should also pay attention to one of the main factors that generate demand for tourism, that is the free time. UNWTO report[1] argues that along with economic development the amount of free time increases, which means that as long as the economy improves, also the demand for tourism in a given population increases. On the other hand, modern man feels greater pressure on time, and thus much more appreciates the free time, intending to spend it as good as possible. In terms of interest in tourism offer this causes the potential customer to have higher expectations[1].The globalization processes are also of substantial importance, as tourists become more and more familiar with foreign cultures. At the same time they start to search more exotic offers, than they used to search in the past. As some German reports[22] point, the increase in foreign travel and a drop in domestic travel should be expected in near future. A gradual change in the structure of travelers has also been noted, with the increasing importance of senior citizens and families with only one child, constant or slightly rising share of people with health problems (health tourism), and also in the behavior of travelers, namely the lower seasonality, more car journeys, more cultural tours and journeys with a focus on health and nature. Thus, the health needs of society will be increasingly combined with recreation and the health tourism is going to be one of the key forms of tourism.The consequences of demographic changes are not short-term, because the demographic phenomena probably will not change during the next few decades. We can expect therefore on the side of tourism industry attempts to adapt to the new needs, or actually to the change of the quantitative and qualitative structure of needs.Each of these demographic factors affect the demand for tourism services, but attention should also be paid to the fact that this is an effect dependent both in its intensity and direction on the type of practised tourism. An aging of population will have a different effect in the case of qualified tourism, and quite another in health tourism. While statistics indicate a lack of noticeable impact of demographic change on business tourism, it's impact on the demand for health tourism may be quite significant.In case of Poland we predict the upward trend in the number of spa visitors to reverse in in the next decade. This forecast was created by taking into account the impact of key categories of patients' age on the total number of patients in the years 1995-2009. Models made based on other age groups give the same result. This seems inconsistent with the hypothesis on the positive impact of the aging of population on health tourism. The basic question is therefore: where is the truth?We can raise few reasons for the projected phenomenon as follow:A. the influence of a demographic cycle.Periodicity of changes in the number of patients may be caused by the cyclical nature of demographic trends. Current members of the age group 50-59 are children of the population boom, the same is in the case of people aged 25-29. These are the two age groups, which are stimulants. At the same time people aged 40-44 and 60-64 were born during the population depression. These are two age groups, which are destimuli. Having regarded to the fact, that the “age” variable has both age ranges that are stimulants and destimuli, undoubtedly it is a nominant variable indicating the need to elaborate a strategy for the development of medical tourism in Poland In case of Poland it was caused by a large loss of population during World War II and revival of the reproductive behavior during the post-war period. The effect of this is observed at intervals of generations as a weakening demographic echo. The decline in the main group of buyers of health tourism services can also reduce the overall number of patients. It is worth noting, that sex is also going to influence the analyzed phenomenon in a different way, as women are going to dominate in the structure of population.B. The influence of the general number of population in PolandAs mentioned, the growth rate of population aged 65 years or more is significant, as in the past three decades the share of this group in general population has risen from 12% to 17%, and over the next five decades, this share is going to double. In seeking the reasons for such a rapid increase in the percentage of seniors we should pay attention on two arguments having a decisive influence on this phenomenon. The first is of course a growing number of people aged 65 years and more. However, its pace is not as high as the growth of seniors, so the second argument may be a change of the point of reference, in this case the number of Polish and European populations. Thus, despite an increase in the proportion of people aged 65 years and more, picture of the dynamics of population growth in this age group is overestimated. This phenomenon is even exacerbated by migration of Poles to other European countries, mainly because young people emigrate.We can assume that a greater importance for the shape of the curve of number of patients in Polish spas will come from the occurrence of demographic booms and depressions, which cyclicality will however be reduced by the diminishing population of Poles. In summary it can be stated that the forecast regarding number of patients in the coming decades indicate the trend to stabilize, and in subsequent decades its dependence on the population booms and depressions will decrease in favor of increasing the population aged 65 years or more. Smoothing the long-term fluctuations in the number of patients can therefore mean the stabilization of this number.

6. Conclusions

- The demand for the health tourism services is a complex phenomenon, which is influenced and stimulated by a number of factors. It is not, therefore, possible to present a fully reliable forecast of the number of patients arriving to health resorts. Some of the factors, as for example the change of touristic behavior in term of recreation, improving economic situation and welfare seems to stimulate in a positive way. On the other hand, the evolution of a family model or globalization may negatively influence the demand for health tourism services, and some of the factors are unambiguous, as it is in case of migrations, which on the one hand negatively influence the age structure in Poland, but on the other in future may result in an increased number of visits from outside the country.Demographic changes in this context become a key factor that may enable us to project the trends in the number of patients coming to Polish spas. As it was discussed, those changes are going to be quite dynamic in Poland in the next decades, particularly in terms of aging of the population and the increasing number of older people. While this seemingly should have a positive impact on health tourism sector, a deepened analysis, as it is presented in this paper, shows this impact to be of negative nature. The upward trend observable in recent years in terms of the demand for health tourism in Poland, with a great probability will turn into a downward trend in the forthcoming years. The generally decreasing number of population, if the demographic trends keep their feature, will probably negatively impact this sector also in the further future. The presented results of observations also indicate a possible impact of demographic changes on the cyclical development of the tourist areas, as well as on changes in the business sector related to health tourism. These results suggest that demographic phenomena are another group of factors that should be included in the creation of tourist product, especially in terms of health tourism. Beside of that the obtained results indicate also the need to take account of demographic trends in the strategy of health tourism development. This need is particularly evident in Poland, where the impact of demographic changes on social phenomena in the coming decades is likely to increase. Preventing the deterioration of the demographic situation is limited to the use of intermediate solutions, such as pension system reform based on the prolongation of retirement age. At the same time the reasons of the problems, such as low fertility are not being referred. Similarly, health tourism development strategies are often merely the ad hoc measures, which only temporarily improve the situation, but are not addressing the long-term trends.It seems that the strategy of action for the development of health tourism should include expanding the range of products offered in Polish spas, where the traditional spa services, like medical and rehabilitation treatment, and the modern spa&wellness services should be combined. The modern spa product may be a chance to meet the needs of tourists of all ages, who come for different purposes and have different expectations while visiting the spa.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML