-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Textile Science

p-ISSN: 2325-0119 e-ISSN: 2325-0100

2022; 11(2): 19-26

doi:10.5923/j.textile.20221102.01

Received: Sep. 17, 2022; Accepted: Oct. 8, 2022; Published: Oct. 27, 2022

Epic Environmental Pollution in Little Drops: The Case of Small-Holder Textile Producers in Ghana

Richard Acquaye1, Eric Bruce-Amartey Jnr.1, Kow Eduam Ghartey2

1Department of Textile Design and Technology, Takoradi Technical University, Takoradi, Ghana

2Visual Arts Department, Kwegyir Aggrey Senior High/Technical School, Anomabo, Ghana

Correspondence to: Richard Acquaye, Department of Textile Design and Technology, Takoradi Technical University, Takoradi, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study investigates small-holder textile producers regarding their indiscriminate disposal of waste effluent and the potential danger to humans, aquatic life and the environment. Small-holder textile producers are key stakeholders in textile production in Ghana and they contribute significantly toward job creation and income for the economy. Their activities include but are not limited to yarn dyeing, weaving, batik production, stamping, screen printing, tie-dye and tritik production. Because they are small-scale producers, the environmental protection agency of Ghana does not monitor and control how they dispose of waste dyes and chemicals after usage. The waste dyes and chemicals are thrown into domestic drains, gutters and the immediate surrounding of the workshop or production space. This result in the effluent going downstream with heavy metals which cause water and environmental pollution that affects fish, farming activities and other aquatic life. Case study, a subset of descriptive research was used as data came mainly from books, archives, state institutions and direct observation at small-scale textile production sites. Questionnaires and observation were the main research tools used to assemble the relevant data. This study anticipates that if such negative practices are not checked, the consequences to the environment and general quality of life would be dire in the foreseeable future. As a condition subsequent, the researchers are partnering with stakeholders to assist their transition from unsafe handling of chemicals to safer and healthier disposal of waste chemicals. The study proposes the sedimentation approach to the disposal of liquid waste as a stop-gap measure before a more sustainable management approach is developed in the foreseeable future.

Keywords: Small-holder, Textiles, Pollution, Chemicals, Waste

Cite this paper: Richard Acquaye, Eric Bruce-Amartey Jnr., Kow Eduam Ghartey, Epic Environmental Pollution in Little Drops: The Case of Small-Holder Textile Producers in Ghana, International Journal of Textile Science, Vol. 11 No. 2, 2022, pp. 19-26. doi: 10.5923/j.textile.20221102.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Textile Production in Ghana

- Textiles constitute a fundamental feature of Ghana’s cultural heritage. Its importance in the various stages of the life of the Ghanaian (childbirth and naming, puberty, marriage and burial rites, festivals etc.) cannot be over-emphasized. Ghana’s textile industry is mainly concerned with the production of fabrics (Ghanaian wax prints, Kente, batik and tie-dye) for use by the garment industry and also for the export market. The sub-sector is predominantly cotton-based although the production of man-made fibres are also undertaken at the small-scale level [1] [2] [3]. Knott [4] agrees with the assertion above, as she notes that Ghana has a rich history of textile production, making different fabrics from woven Kente to brightly-coloured batik to wax prints where designs carry meanings. Indeed, textile manufacturing in Ghana is an industry consisting of ginneries and textile mills producing batik, wax cloth, fancy printed cloth and Kente cloth. Firms have located in Ghana to serve local and regional markets with printed African patterned fabrics. The industry has shown signs of significant growth in recent years, promoting high-quality traditionally designed fabrics as “Made in Ghana” to niche markets, especially the United States of America [5] [6]. Ghanaian textile companies prefer to locate within designated and industrial areas to take advantage of Ghana’s free zone regime and stable operating environment. Today, Ghana’s textile industry includes vertically integrated mills, horizontal weaving factories and the traditional textile manufacturing firms involved in spinning, hand-weaving and fabric processing [5]. Addotey and Ahene-Nunoo [7], indicated that one of the major sources from which hazardous and industrial waste is generated in Ghana is the textiles industry, that is, from pre-treatment, dyeing to printing among others. The study noted that the waste disposal practices of several batik and tie-dye producers in many parts of Ghana are hardly regulated, thereby culminating in indiscriminate disposal of waste, which tends to endanger the lives of people and the environment. The study, therefore, seeks to identify, examine and document the waste disposal practices of batik and tie-dye producers within the metropolitan areas of Accra, Cape Coast, Takoradi and Kumasi, and proffer solutions to challenges that may be identified in the findings of the study.

1.2. Waste Management in Ghana

- According to a National Report for Ghana presented at the 18th Session of the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development, to address the problem of waste management, the government has over the years put in place adequate national policies, regulatory and institutional frameworks. An Environmental Sanitation Policy was formulated in 1999 and later amended into a strategic action plan developed for implementation. A number of relevant legislations for the control of waste were designed and enacted. These include the following: Local Government Act, 1990 (Act 462); Environmental Assessment Regulations, 1999 (LI 1652); Criminal Code, 1960 (Act 29); Water Resources Commission Act, 1996 (Act 522); Pesticides Control and Management Act, 1996 (Act 528); National Building Regulations, 1996 (LI 1630). Beyond these legislations, the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development, Ministry of Environment, Science and Technology in collaboration with the Environmental Protection Agency have prepared the following guidelines and standards for waste management: National Environmental Quality Guidelines (1998); Ghana Landfill Guidelines (2002); Manual for the Preparation of District Waste Management Plans in Ghana (2002); Guidelines for the Management of Healthcare and Veterinary Waste in Ghana (2002); Handbook for the Preparation of District level Environmental Sanitation Strategies and Action Plans (DESSAPs). These policies and guidelines target large-scale production and industry players unwittingly leaving out small-scale producers in Ghana. Meanwhile, collectively indiscriminate waste disposal by these small-scale producers is ricking havoc on the environment. The Metropolitan, Municipal or District Assemblies are the key institutions responsible for the management of sanitation and waste at the local and community level. They are, however, supported in this task by several other institutions and organisations including the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Disaster Management Organisation (NADMO). Major wastewater treatment methods found in Ghana include stabilisation ponds, trickling filters and activated sludge plants. According to a recent survey, there are 46 wastewater treatment plants in Ghana. More than half of all treatment plants in Ghana are in the Greater Accra region, mainly in the capital city of Accra and the port city of Tema. The stabilisation pond method is the most extensively used with almost all faecal sludge and large-capacity sewage treatment plants using the method. Most trickling filters and activated sludge plants recorded have a low capacity and belong to private enterprises such as larger hotels [8]. Akwaa Marfo [9] as well as [10], contend that only about 10 of the treatment plants are operational, and it is not clear if these plants meet the EPA effluent guidelines. This can be attributed to the fact that the conventional methods are energy-dependent and also when the mechanical parts become faulty, the part has to be imported making them too expensive to maintain. Low-cost, low- technology methods are however manageable. According to Amegatse [11], one of the major challenges in the management of solid waste in Ghana is the collection and disposal process, which are labour-intensive and often not effective. In urban cities in Ghana, issues relating to proper solid waste disposal are a major challenge for the local government authorities. City authorities and waste companies are often overwhelmed by the volume of waste generated daily. The lack of well-planned and efficient strategies to manage waste is one reason for the poor state of solid waste management, particularly by municipal authorities in Ghana. Aishwariya & Jaisri [12], argue that the textile industry is one of the most pollutants-releasing industries in the world. They further pointed-out that, surveys show that nearly 5% of all landfill space is consumed by textile waste. Besides, 20% of all fresh water pollution is made by textile treatment and dyeing [12]. This assertion is confirmed by the European Parliament [13], as it notes that, textile production is estimated to be responsible for about 20% of global clean water pollution from dyeing and finishing products. It further postulates that clothes, footwear and household textiles are responsible for water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions and landfill. Even though the colour is the foremost attraction of any textile material, it may cause hazards to the environment and living beings. Indeed, different synthetic dyes and their auxiliary chemicals are used for achieving required or desired colour effects [14]. However, synthetic dye is very toxic and hazardous to the environment. The presence of different dyes such as sulphur, azoic, indigoids, nitrates, acidic acid, soap, enzymes, complex compounds, heavy metals and certain auxiliary chemicals all make the textile effluent highly toxic. Thus, the effluent from the dyeing and printing industry carries many dyes and other additives which are added during the colouring process. These are to be delivered easily through lakes and rivers especially because they have high water solubility. They may also degrade to form products which are highly toxic and carcinogenic. Thus, these dyes are harmful to living organisms [14]. This is affirmed by Afena et al. [15] as they opine that, the problems associated with coloured textile effluent include the introduction of heavy metals into water bodies, an increase in biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), pH and suspended solids. Furthermore, the presence of synthetic dyes in waste water makes the water smell unpleasantly, and aesthetically less pleasing as well as decreasing the amount of sunlight penetrating the water, thereby affecting photosynthesis and entire aquatic ecosystems. Also, most of the dyes that are released into water bodies, including their breakdown products, are toxic, carcinogenic, mutagenic and teratogenic to humans and other life forms [15]. Waste generation in the small-scale textile industry cannot be avoided so long as there is demand for local textiles. The waste can only be controlled and managed through innovative ways to prevent pollution of river bodies, contamination of food, choking of drainage systems and the destruction of fauna by the dyes and chemicals [16]. Waste water treatment in the 16 regions of Ghana is very abysmal, only less than 8% of waste water (domestic) in Ghana undergoes some form of treatment. Most manufacturing factories located along the coast discharge their effluent directly into the ocean without any form of treatment, while those located on land discharge their effluent into major streams and urban storm drain [17].

1.3. Ghana

- The Republic of Ghana is a country located in West Africa and borders the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south. The country shares land borders with Côte d'Ivoire in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Togo in the east. Ghana covers an area of 238,535 km2 (92,099 sq mi), spanning diverse geography and ecology that ranges from coastal savannahs to tropical rain forests. With over 31 million people, Ghana is the second-most populous country in West Africa, after Nigeria. The capital and largest city is Accra; other major cities include Kumasi, Tamale and Sekondi-Takoradi [18]. Ghana is an average natural resource enriched country possessing industrial minerals, hydrocarbons and precious metals. It is an emerging designated digital economy with mixed economy hybridisation and an emerging market. It has an economic plan target known as the ‘Ghana Vision 2020’. This plan envisions Ghana as the first African country to become a developed country between 2020 and 2029 and a newly industrialised country between 2030 and 2039 [19].As of March 2022, Ghana has a population of 32.37 million. About 29% of the population is under the age of 15, while persons aged 15–64 make up 57.8% of the population [18]. The population distribution has 5,440,463 in Ashanti, 1,208,649 in Bono region, 2,859,821 in Central, 2,925,653 in Eastern, 2,060,585 in Western, 2,310,939 in Northern Region, 880,921 in Western North and 5,455,692 in in Greater Accra, 1,659,040 in Volta, 658,946 in North East, 747,248 in Oti, 653,266 in Bono East, 1,301,226 in Upper East, 901,502 in Upper West 1,203,400 in Bono East and 564,668 in Ahafo [18].

| Figure 1. Map of Ghana (Source: https://ontheworldmap.com/ghana/) |

2. Research Methodology

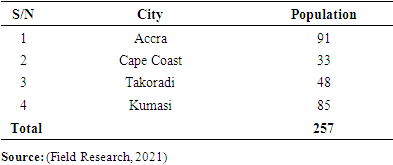

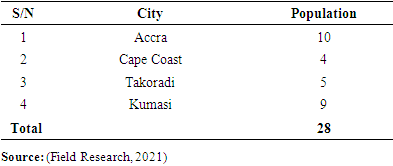

- The study used a descriptive research approach which aims at collecting data to describe the social system, relations and social events of the study area [20]. The descriptive design attempts to collect data from particular members of the population to respond to questions regarding the current status of the research problem. And in this instance, the problem is the indiscriminate disposal of liquid waste by small-holder textile producers in Ghana. Research tools such as questionnaire/interview schedule, focus group discussion and observation checklist were used to collect data. The population for the study includes the proprietors, employees, and customers of small-holder textile producers based in the four cities of Ghana, Accra, Kumasi, Takoradi and Cape Coast. The researchers targeted textile producers in these cities because they wanted individuals who were in the best position to offer the kind of information needed for the study. As reported in Tables 1 and 2 below, the target population was 257 in all the selected cities listed above, out of which 28 were accessible.

|

|

3. Findings and Discussion

3.1. Age/Sex/Education Composition of Respondents

- The study was conducted between December 2021 and June 2022 and was based on both structured and unstructured interviews as well as focus group discussions with purposively sampled respondents who engage in textile dyeing and printing within the Metropolitan Areas of Accra, Cape Coast, Sekondi-Takoradi and Kumasi. They were between the ages of 31 and 53. The study was evaluated based on a qualitative analysis of the data acquired together with some supplementary interpretation. The purposively sampled individuals whose opinions are included in the study were representative of the practitioners of the small-scale textile dyers and printers within the areas mentioned above. The sample comprised 28 individuals out of which 11, representing 39.29% were males, and 17, representing 60.71% were females. In educational terms, 6 representing 21.4% were university graduates, 8 representing 28.6% were senior high school graduates, and 14 representing 50% were junior high school graduates. The focus group discussion was particularly held for 13 dealers in textile dyes and auxiliary chemicals. They were invited to Takoradi on a special arrangement (their food, transportation cost and stipends were fully borne by the researchers) in January 2022. Given the nature of the research and the possible outcomes, the respondents strongly pleaded the identities of their organisations be kept under strict anonymity for fear of prosecution.

3.2. Dyes and Chemicals Used

- The study revealed that there are two main types of synthetic dyes employed by small-scale textile dyers in Ghana. They are vat and reactive dyes and each of these dyes has separate auxiliary chemicals with which they function properly. Thus, for Vat dyes, the auxiliary chemicals used are sodium hydrosulphite, caustic soda, and sodium hydroxide; and for reactive dyes, the auxiliary chemicals used are soda ash and salt. With the exception of salt, all the chemicals and dyes mentioned above are harmful to the environment and its inhabitants, including plants, aquatic life and human beings. The study further revealed that Synthetic dyes are more widely used than natural dyes because, they are cheaper readily available in different colours, and have desirable fastness properties. There is also scouring and bleaching at the small-scale level that utilises chemicals such as sodium hypochlorite, sodium hydrochloride and anionic surfactant - sometimes in high concentrations. Figure 2 is a demonstration of scouring and bleaching process at the local level.

| Figure 2. Scouring and bleaching of yarns before dyeing (Source: (Field Research, 2021)) |

3.2.1. Dyeing Methods

- The study revealed that the following were the main methods of dyeing employed by small-scale textile producers:Yarn dyeing This is a form of dyeing textile yarns in the form of hanks and skeins prior to the process of weaving. The yarn dyeing process is shown in Figures 3 and 4. The yarn dyeing process can be done in either partial immersion or total immersion of the yarn.

| Figure 3. Yarn (hank) dyeing with reactive dye (Source: (Field Research, 2021)) |

| Figure 4. Sorting yarns (hanks) for drying (Source: (Field Research, 2021)) |

| Figure 5. Small-scale dyeing (Source: (Field Research, 2021)) |

| Figure 6. Small-scale dyeing (Source: (Field Research, 2021)) |

3.3. Waste Management Practices

- In this section, the study discusses the poor liquid waste management practices of small-holder textile producers, which cause a great threat to environmental sustainability and the ecosystem.

3.3.1. Waste Characteristics

- The study revealed that the main and conspicuously noticeable waste is found in different colours, in effluents discharged from production sites of small-scale textile manufacturers are a mixture of dyes, including auxiliary chemicals and other pollutants such as candle and or bee’s wax which are residues from dewaxed fabrics from batik processes. Additionally, water used for washing and rinsing of dyed fabrics, end-up in drains and by extension, natural water bodies. The study further revealed that local producers do not buy dyes and chemicals in bulk; therefore, they do not deal with dye and auxiliary chemical packaging materials which have stringent and quite complex disposal methods. Nonetheless, the plastic packaging materials that contain the dyes and chemicals bought by local producers usually end up at landfill sites.

3.3.2. Disposal into Drains

- The study revealed that most of the respondents interviewed disposed of liquid waste into drains. Indeed, all the respondents confirmed that they use several gallons of water daily. The study further found out that, to produce a kilogram of fabric, about 20 litres of water is consumed, thus, washing the fibre or fabric, dyeing and then washing and rinsing the finished product after oxidation. It also involves the usage of chemicals and other solvents that culminate into liquid waste. Such liquid waste arises mainly from wet-finishing treatments, where large volumes of water and chemicals are used. The study again revealed that all the dyes and chemicals used by local tie-dye and batik producers are synthetic and therefore, not readily biodegradable and environmentally friendly. The waste water generated during these processes is, therefore, highly polluted, dangerous and discharged into drains that feed water bodies without appropriate treatments. This practice has the potential to severely harm aquatic life, along with several people such as subsistent farmers, who are dependent on the water for their day-to-day livelihood.

3.3.3. Disposal of Soil

- The study also revealed that most local dyers dug pits and buried chemical waste(s) in them. As many as 22 out of the 28 respondents engaged, representing 78.6% confirmed that they regularly buried chemical wastes into the soil as a means of disposing of them. The study deems it instructive to note that, the soil is the fundamental component of the ecosystem and healthy soil helps in absorbing carbon dioxide. The depletion of soil nutrients leads to crops with low nutrition content, and with chemical contents adverse to human health, leading to a human population with low immunity and various diseases [23].

3.4. Air Pollution

- Unregulated gaseous wastes from the operations of smallholder textile producers containing solvent vapours such as sodium hypochlorite, hydrosulphite and smokes that emanate from the heating waxes, as well as the improper burning of production waste, are normally diffused into the atmosphere, poisoning the air and ladening it with harmful chemicals. These can cause health hazards such as acute respiratory disorders. Thus, there is a need to use proper methods to suppress the dust and avoid making it reach the air limits.

3.5. Reasons for Adverse Waste Management Practices

- The study revealed that the following are the main reasons for the poor waste management practices of local textile dyers and printers.

3.5.1. Lack of Awareness of Sustainability

- Out of the 28 respondents engaged, 24 representing 85.7% admitted to not having in place sustainable practices such as recycling in managing textile waste. The study revealed that the disposal behaviour of these producers and their awareness of the environment can play a crucial role in reducing waste. At the end-of-life stage, instead of disposing into drains or landfill, if producers become more open to reusing or recycling, it will certainly reduce textile waste to an appreciable level.

3.5.2. Lack of Eco-Friendly Practices

- 28 out of the 28 respondents representing 100% of the totality of the interviewees engaged, admitted to not knowing Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS), which is a document that contains information on the potential hazards (health, fire, reactivity and environmental) and how to work safely with the chemical product. The respondents also admitted that fabric dyeing and printing result in wastes that are not recycled effectively. They also admitted to not having eco-friendly methods for treating the waste water generated from dyeing.

3.5.3. Lack of Monitoring and Enforcement by Regulatory Authorities

- Nineteen (19) out of the 28 respondents representing 68% of the total interviewees, revealed that they had never been approached by the neither Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) or the Metropolitan, Municipal and or District Assemblies (MMDAs) for questioning about their waste management practices. The other 9 respondents representing 32% of the total interviewees mentioned that they had been approached several times by officials of the MMDAs, but mostly for the payment of taxes. The study revealed that legislation regarding the protection of the environment in Ghana is quite stringent but poorly enforced. The geographical positioning of these smallholder textile enterprises is either poorly worked out or done on the blindside of regulatory authorities such as the EPA, and the MMDAs through their various Directorates of Environment and Health as Well as Waste Management. Therefore, government initiatives and strict policies for the protection of the environment, disposal of waste and awareness can be of great help to save the environment. From the above, it could be inferred that regulatory authorities have failed in working in the direction of streamlining the flow of waste, proper disposal of waste, consumer awareness and strict norms.

3.5.4. Appropriate Methods of Waste Disposal

- • The disposal of textile waste must be done through incineration, decomposition and accumulation without posing any threats to people and the environment. Because the modern consumer is especially concerned about human ecology and that production ecology is complex, versatile and difficult to screen, studies have focused on human ecology in particular.• Contamination of underground water reservoirs and drinking water by chemicals must be prevented and the personnel responsible for storing and disposing of these chemicals must possess the required qualifications. It would be much better if the chemical waste is disposed of by a specialized firm.• Chemical substances must not be mixed with other waste materials.• Storing and burning wastes in open areas must be prohibited.• Waste materials must be kept in safe areas in a way that they would not pose any threat to employers and their employees. • Waste water must be treated at a wastewater treatment plant, liquid and solid oil must be passed through separate filters. They must be emptied and cleaned regularly and the contents must be disposed-off properly.• The EPA has to support small-holder producers to create, log books that itemise chemical items for disposal, showing at a minimum: item name, quantity, and date available for disposal.• Producers must be sure to have the Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) for the chemical item(s) before inquiring. An MSDS is ordinarily shipped with a chemical; these sheets should be kept on file for a reference regarding the disposal of waste(s).• Document the means of disposal (e.g., drain or contractor), including disposal date, in the logbook.

4. Conclusions

- The study sought to uncover the danger posed by the unregulated activities of cottage textile dyers and printers in Ghana due to their use of diverse textile chemicals which are environmental pollutants. The liquid and solid effluents from the operations of small-holder textile producers, have caused and are still causing major destructions to the environment, ecology, agriculture, aquaculture and public health in many parts of the country. Ahene-Nunoo [24] notes that waste(s) generated by smallholder textile producers in Ghana, constitute 114 tons daily. This conservatively translates into about 41,000 tons a year. Given the findings of the study about the unhealthy disposal practices currently being undertaken, the lives of the people of Ghana as well as all other living organisms remain in danger.The study revealed that there were no dedicated infrastructure and capacity to manage production waste; a lack of skill in waste management; a perceived low sense of responsibility towards collecting and or disposing of production waste, low-risk perception of the harmful effects of production waste, poor attitudes towards solid waste management within and around production sites, and other factors adversely affect the effective management of production waste in the study areas. In general, the findings of the study corroborate existing literature that shows a lacklustre approach to waste management in Ghana.Regulatory authorities must therefore work hand-in-hand with small-holder textile producers to invest in recycling, redesigning, upcycling, downcycling, restoring, repairing, reusing and reducing are some of the techniques used by the industry. Consumers should be aware of the choices they have and also try to become part of the sustainable chain. Green consumerism has changed the face of the textile industry, which is now recognised for its efforts taken to reduce wastage and infuse eco-friendly practices.

5. Recommendations

- • Regulatory authorities must create awareness regarding the use of material safety data sheets (MSDS) which includes information such as the properties of each chemical; the physical, health, and environmental health hazards; protective measures; and safety precautions for handling, storing, disposal and transporting such chemicals.• The government through the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), must designate areas for textile dyeing activities to make it easy for regulation. Additionally, the EPA must ensure that national legal directives about the protection of the environment must be implemented.• Government must invest in effluent treatment plants (ETPs) for such activities where dyers/printers would be legally obliged to patronise and be charged for the services rendered to them.• Additionally, the Ministry of Sanitation and Water Resources in collaboration with MMDAs must build Publicly Owned Treatment Works (POTW) in the short to medium term, as is done in advanced jurisdictions. This would help in the storage, treatment, recycling, and reclamation of industrial wastes of liquid nature. Small-holder textile dyers and printers would then be legally required to patronise the services of POTWs at a fee, since losing the environment and its living organisms is much costlier than the charges to be paid by these practitioners.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We wish to extend our warmest appreciation to members of the Department of Textile Design and Technology, Takoradi Technical University, Takoradi – Ghana for their immense support. And to Mr. Emmanuel Vidzro, our driver for all the numerous sacrifices he made towards the collection of data throughout the period of the study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML