-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Surgical Research

p-ISSN: 2332-8312 e-ISSN: 2332-8320

2025; 13(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.surgery.20251301.01

Received: Sep. 27, 2025; Accepted: Oct. 20, 2025; Published: Oct. 25, 2025

Non-operative Treatment of Blunt Spleen Trauma in Adults

M. Habarek, A. Bentabet, S. Merzouki, A. Aissat, A. Matmar, S. Ait Hamadouche

Department of General Surgery TiziOuzou, Teaching Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, University MouloudMammeri of TiziOuzou, Algeria

Correspondence to: M. Habarek, Department of General Surgery TiziOuzou, Teaching Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, University MouloudMammeri of TiziOuzou, Algeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: The treatment of blunt splenic trauma has evolved to a large extent toward nonoperative treatment through the evaluation and increasing use of computed tomography (CT). The aim of our study was to analyze and evaluate the results of nonoperative treatment of blunt spleen trauma in adults. Material and Methods: This retrospective study was carried out on adult patients with blunt traumatic lesions of the spleen and who were hospitalized in the visceral and digestive surgery department of the University Hospital. of Tiziouzou (Algeria) from 2016 to 2023. The variables studied were extracted from the medical files of the patients. Results such as complications, mortality rate and risk factors were noted. Results: We recorded a total of 134 cases of blunt spleen trauma, making 31% (134/440) abdominal trauma. The average age of the patients was 36 years [17 – 72 years] of which 93 (69.41%) were men. Ninety-six (N= 96) patients (71.6%) immediately underwent emergency operative treatment, which represents group I, 28.4% of patients (n= 38) were admitted for a conservative non-operative treatment. Non-operative treatment could be successfully applied in 76% of cases (N = 29) which represents group II, and in 24% of cases (N = 9), it was necessary to perform a secondary splenectomy and which represents group III. In total, 21.6% of patients had non-operative conservative treatment and 78% had a laparotomy immediately or after admission. The mechanism of injury was not significantly different between the 3 groups. Traffic accidents were the most common cause. The failure rate of conservative treatment gradually increases with the stage of splenic damage. Emergency management involved splenectomy in 92% and splenorrhaphy in 8%. In group III, there were 89% splenectomy and 11% splenorrhaphy. Postoperative complications were observed in 10.4% and 45.7% of the non-operative and operative groups, respectively (p=0,006). The mortality rate was 16.2% and 3.4% in the operative and non-operative groups (p = 0,021). Conclusion: The final decision for emergency laparotomy for blunt trauma to the spleen should be based on the clinical condition and hemodynamic situation of the patient. Above all, the contribution of the scanner allows correct triage of patients who could benefit from non-operative treatment.

Keywords: Spleen, Trauma, Non-operative treatment, Splenectomy

Cite this paper: M. Habarek, A. Bentabet, S. Merzouki, A. Aissat, A. Matmar, S. Ait Hamadouche, Non-operative Treatment of Blunt Spleen Trauma in Adults, International Journal of Surgical Research, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.surgery.20251301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

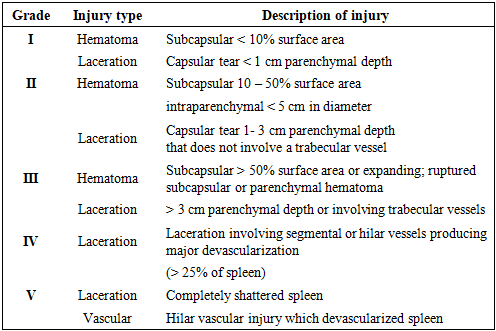

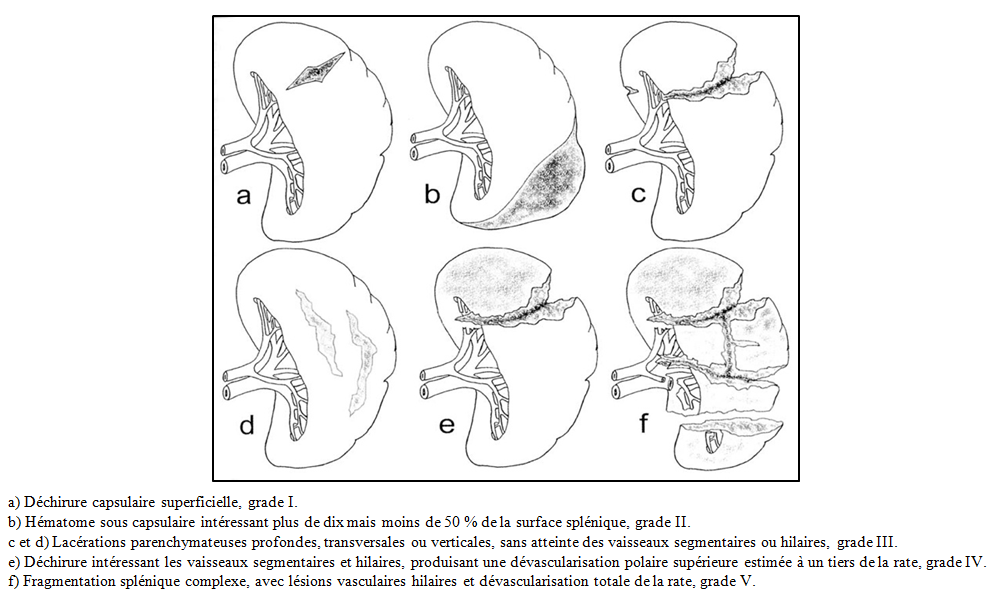

- The spleen and liver are the organs most frequently injured in abdominal trauma [1]. Close trauma to the spleen, often secondary to road accidents, is a frequent reason for admission to visceral and digestive surgery emergencies. The advent of ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) has changed their management [2]. The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) has classified splenic injuries from I to V [3], see Table 1. Over the past three decades, the management of splenic injuries has evolved toward a more conservative and non-operative approach. This attitude reduces the complications of splenectomy and laparotomy. The main condition for this choice is hemodynamic stability or a satisfactory response to initial resuscitation. However, computed tomography (CT) may underestimate the degree of injury compared to operative findings [4]. Numerous retrospective studies have shown that splenic injuries can be safely managed non-surgically through the selective use of arterial embolization [5]. Failure rates appear to vary from 8 to 38% [6–10]. Mortality linked to splenic trauma varies between 4 and 18% [11]. The aim of our study was to analyze and evaluate the results of non-operative treatment of blunt trauma to the spleen in adults.

|

| Figure 1. Représentation schématique des lésions traumatiques de la rate, avec leurs grades selon la classification de l’American Association for the Surgery of Trauma |

2. Material and Methods

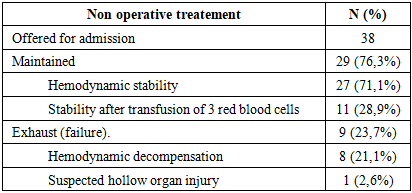

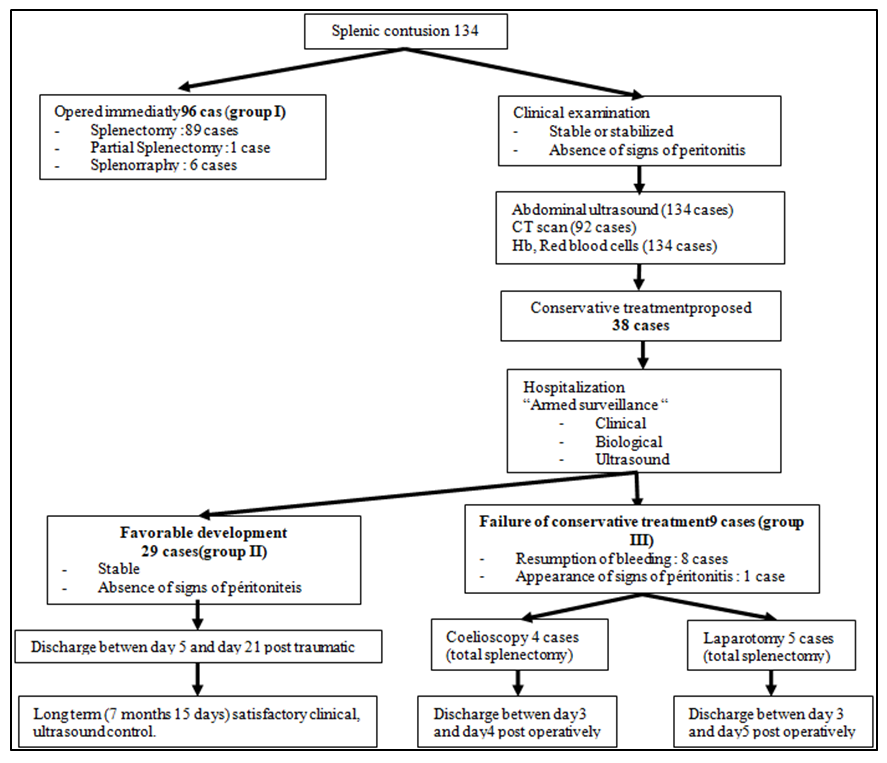

- This retrospective, single-center, prognostic study was conducted on patients hospitalized in the visceral and digestive surgery emergency department of the TiziOuzou University Hospital Center from 2016 to 2023 (8 years) and diagnosed with blunt splenic trauma. The database of the TiziOuzou hospital department and emergency department was used to identify eligible patients and the required information was extracted from the patients' medical records.This information included demographic data, mechanism of injury, AAST scores of splenic injuries assessed and determined from the CT scan performed on admission, level of consciousness (based on the Glasgow Coma Scale), signs of peritonitis on abdominal examination (tenderness and/or generalized abdominal contracture), and signs of shock on admission to the emergency department (systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure less than 60 mm Hg or a heart rate greater than 100 beats per minute were considered hemodynamically unstable), initial laboratory results, therapeutic method, length of hospitalization, number of blood transfusions received, presence or occurrence of complications (hemorrhagic shock, intestinal obstruction, infectious complications including pneumonia, sepsis, wound infection, urinary tract infection, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, liver or kidney dysfunction and abscess intra-abdominal). The medical history of patients, as well as failures of conservative treatment (patients requiring additional and delayed procedures, such as partial or total splenectomy, splenorrhaphy).We adopted a defined protocol (Figure 2) for splenic preservation in patients with stable or stabilized hemodynamic status, after transfusion of less than 3 red blood cells, without suspicion of hollow organ perforation. An "armed" surveillance approach was based on clinical examination, with measurement of BP, pulse, conjunctival examination several times a day and abdominal examination once a day, blood count once a day, CT scan and/or ultrasound (hemoperitoneum control) on admission and then at 48 hours.

| Figure 2. Patient management algorithm in the series |

3. Results

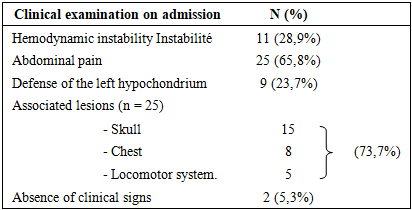

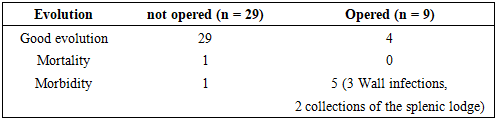

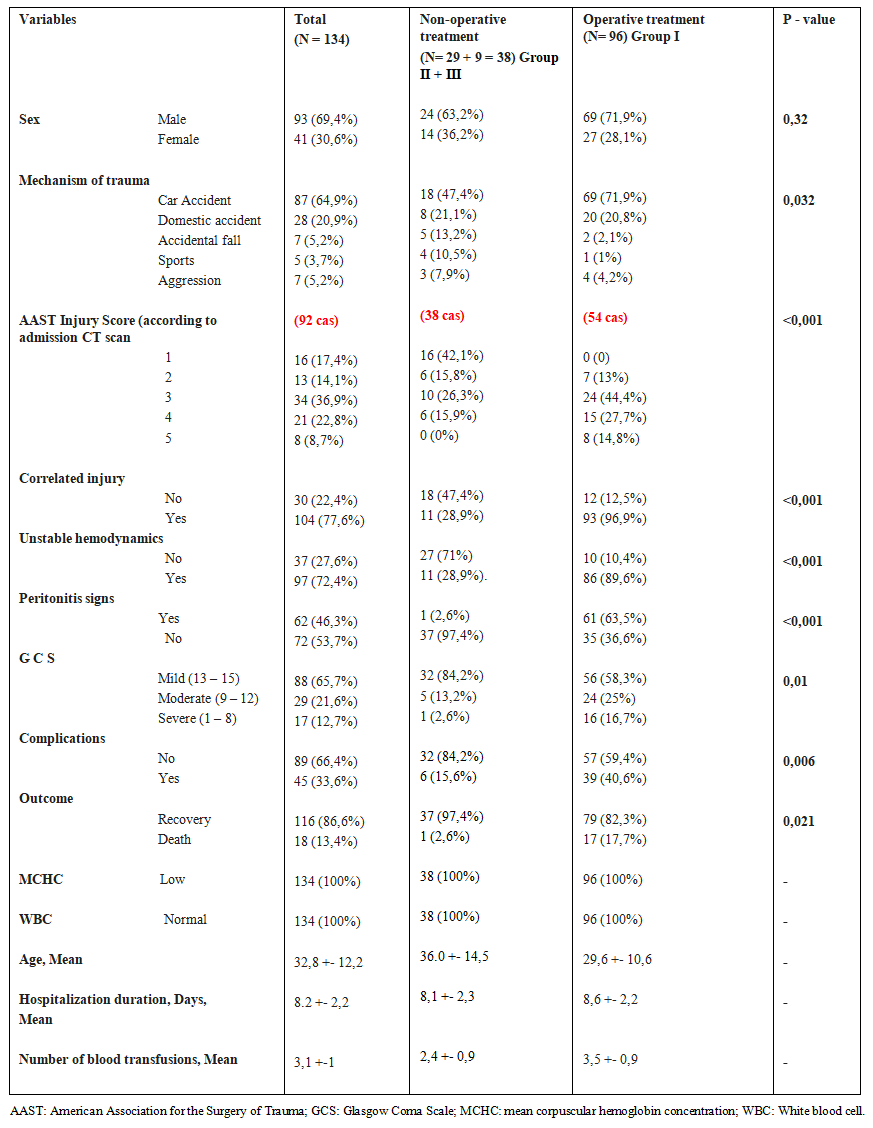

- Our study involved 440 patients with trauma (closed and open) of the abdomen, treated at the emergency department and the visceral and digestive surgery department of the TiziOuzou University Hospital Center for 8 years (from January 2016 to December 2023). Among them, 134 patients (30.5%) suffered from closed trauma of the spleen and 96 (71.6%) were operated on immediately, which represents group I. A total of 38 patients were proposed to non-operative treatment and studied. The failure rate of conservative treatment was 23.7% (9 cases), which represents group III. The evolution was favorable in 76.3% (29 cases), which represents group II. The average age was 36 years (17 to 72 years). The sex ratio was 3 men for one woman. The demographic characteristics of the patients, the clinical and morphological examination results (radiological, biological) as well as the therapeutic strategies are presented in Table 2.

| Table 2. A comparison of patients managed operatively and non-operatively |

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- Road traffic accidents are the main cause of splenic contusions [2,12,13]. Young male subjects are most affected [13,14,15]. Splenic contusions are part of polytrauma in 2/3 of cases and the spleen is injured in 46% of polytrauma [2,16]. In our study, splenic trauma represents 30.5% of all traumatic injuries of the abdominal viscera during abdominal contusions.Given the risk of infection (which is all the more serious when the subject is young) [17], the immunological role of the spleen, particularly in children [2], and the restrictive measures that the splenectomized person will have to undergo for life, non-operative treatment has gradually become established. In addition, splenectomy exposes the patient to the complications of any laparotomy (occlusion, postoperative eventration, scarring). Moog et al. [2] operated on a single case of splenic trauma in 88 children. The average success rate of non-operative treatment of the spleen is 90% in children [18,19]. On the other hand, in adults, surgical abstention was slow to become established and only concerned 25% to 30% of injured patients [20,21]. This was probably explained by more violent trauma and a greater frequency of associated intra-abdominal injuries. In our series of 134 splenic injuries treated between 2016 and 2023, there were 87 and 28 cases successively linked to traffic accidents and domestic accidents, with successively performed 69 (79.3%) and 28 (71.4%) immediate splenectomies. Currently the abstention rate has increased to between 60 and 85%. During laparotomy, many splenic injuries stopped bleeding, an argument in favor of conservative treatment and the development of surgical abstention [22]. A French study [23] did not count any emergency splenectomies for 65 consecutive splenic injuries in children under 15 years of age. In adults, between 55% and 80% of patients with splenic trauma currently benefit from non-operative treatment [24]. The average success rate of abstentionist behavior is now 80 to 90% in adults [15,18,25-28].This rate increases with the use of splenic arterial embolization [15,28-30]. In a series of 164 cases of splenic trauma, the authors were able to perform embolization treatment in 24 patients, in 3 cases after recurrent bleeding [29]. This resulted in a success rate of non-operative treatment of 98%. Also, in another published series of 317 cases, the authors were able to reduce the rate of patients operated on by 16% thanks to the use of embolization [30]. Finally, in the French multicenter series [28] the rate of spleen salvage after embolization was 91%. In our series, we only had a rate of 21% (18 cases) and 28.6% (8 cases) of spleen salvage in the 87 cases of traffic accidents and the 28 cases of domestic accidents. We did not use splenic arterial embolization at any time.Despite the growing trend to favor conservative management over surgical management, determining the best treatment for each patient remains undecided because the wait-and-see option must meet strict conditions: hemodynamic stability, no suspicion of hollow organ lesions [31], "armed" and sustained clinical monitoring in a surgical intensive care setting and availability of morphological examinations.The morphological examinations necessary to retain the conservative option are CT and ultrasound. CT is the reference examination. But its cost, the radiation generated and the difficulty of performing it in certain patients due to post-traumatic agitation limit its use. Ultrasound is the second examination allowing to monitor patients. In fact, a reassuring clinical examination and an ultrasound with normal renal Doppler are sufficient to opt for non-operative treatment [16]. Its use in adults is common practice with high sensitivity, and its effectiveness is accepted [19-22]. There is a growing trend (especially for American centers) to perform abdominal ultrasound (FAST ultrasound: Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma) systematically in the initial evaluation of all polytrauma patients regardless of hemodynamic stability. It is performed by the surgeon himself to highlight the hemoperitoneum [23-25]. In our series, we performed 92 CT scans and 134 ultrasound scans, which was sufficient to successfully monitor 38 patients.Monitoring should be provided in a surgical department with an intensive care unit or in a surgical intensive care setting. In our series, all patients were monitored in the intensive care unit of the surgical emergency department and the visceral and digestive surgery department of the hospital. Monitoring was provided by the on-call teams.Patients hospitalized in intensive care are transferred to the visceral and digestive surgery department as soon as the patients' general condition permits (level of consciousness, resumption of bowel movements). Ultrasound checks are performed every 3 to 4 days [2]. Some authors recommend a follow-up CT scan on day 7 of the injury [32]. In our series, in addition to clinical and ultrasound monitoring, all patients who underwent non-operative treatment underwent CT monitoring during hospitalization.The total duration of hospitalization is short for the most recent series (8 days). This duration of hospitalization is further reduced in the case of splenic arterial embolization [15,27,29]. In our study, patients were hospitalized for an average of 8.2 days with extremes ranging from 5 to 28 days. The cessation of sports activities is prescribed for 6 to 7 weeks for non-contact sports, and for 3 months for more violent sports [33].Complications of non-operative treatment are secondary hemorrhage which complicates 1 to 3% of monitored splenic traumas [34,27,35], splenic abscesses, pseudo-aneurysms of the splenic artery, unrecognized hollow organ injury [34,36], splenic pseudocyst in 0.44% of cases [14]. Other authors [37] have described fistulization of a large splenic subcapsular hematoma in the colon which was managed conservatively with good outcome. Delayed bleeding and unrecognized abdominal injuries correlated with multiple traumas can increase the mortality rate [31]. In our series, we have 8 recurrences of hemorrhage (21%) and one appearance of signs of peritonitis due to hollow organ injury (2.6%).In case of failure of non-operative treatment, laparoscopy can be an alternative to laparotomy in a hemodynamically stable patient. This technique allows exploration of the entire abdominal cavity, evacuation of hemoperitoneum, identification of the source of bleeding, and assessment of the severity of lesions. It also allows the detection and treatment of possible perforations of hollow organs [37]. More recently, this technique has been used to perform total or partial splenectomies, or a hemostasis procedure allowing preservation of the entire spleen. In our series, only 4 out of 9 patients underwent secondary splenectomy by laparoscopic approach.In the EAST multicenter retrospective study reporting the experience of 27 trauma centers in the USA [34], it was found that the more significant the splenic injuries, the less feasible non-operative treatment was (according to Moore grade I, II, III, IV and V injury, non-operative treatment was successfully performed in 75%, 70%, 49%, 17% and 1% of cases respectively). This conservative approach is not without risk: this same work shows a worrying number of avoidable deaths from hemorrhage; in fact, there were 6 avoidable deaths out of 10 deaths of patients in whom the non-operative option had been chosen [39]. The surgeon must therefore constantly keep in mind that the risk of infection underlying this conservative attitude is major in children under 5 years of age, significant in young people under 15 years of age but much lower in adults and that performing a total splenectomy for haemostasis remains a useful and current procedure.The treatment method for splenic injury is determined by the patient's hemodynamic stability, intra- and extra-abdominal injuries, signs of peritonitis, active bleeding, and injury severity [40]. In the present study, the most common splenic injury score was grade 3 on the AAST splenic injury scale; 70.6% of these patients, 71.4% with grade 4, and all those with grade 5 injuries underwent surgical treatment.

5. Conclusions

- Our study shows that non-operative treatment (NOT) for blunt splenic trauma is safe and effective. It should be routinely offered to both adults and children, in cases of hemodynamic stability, subject to reliable imaging and competent resuscitation.

Conflicts of Interest

- None of the authors have any conflicts of interest (financial or otherwise) to disclose.

Funding

- The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML