-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Surgical Research

2015; 4(2): 11-14

doi:10.5923/j.surgery.20150402.01

Laparoscopy in Upper Gastro-Intestinal non Tumoral Pathologies: Our Experience in a Low Income Country

Toure Alpha O. 1, Foba Mamadou Lassana 1, Ka Ousmane 1, Cisse Mamadou 1, Konate Ibrahima 2, Dieng Madieng 1, Toure Cheikh T. 1

1General Surgery Department, Le Dantec Hospital, Avenue Pasteur, Dakar, Senegal

2Surgery and surgical specialties Department, Gatson Berger University, Saint, Louis, Senegal

Correspondence to: Toure Alpha O. , General Surgery Department, Le Dantec Hospital, Avenue Pasteur, Dakar, Senegal.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the contribution of laparoscopy in non-tumoral Upper GastroIntestinal (UGI) diseases in our working conditions. This was a retrospective descriptive study in General Surgery Department of Le Dantec University Hospital in Dakar on a period of 10 years (January 2003 to January 2013). We included 162 cases patients treated by laparoscopy for acute or chronic UGI disease. The pathologies encountered were hiatal hernia in 18.5% of cases (n = 30); achalasia in 13% of cases (n = 21); ulcerative pyloroduodenal stenosis in 55.5% of cases (n = 90); perforated duodenal ulcer in 13% of cases (n = 21). We performed truncal vagotomy and gastric bypass, Nissen Rossetti fundoplication, Heller Myotomy and ulcer sutures as laparoscopic procedures. The average length of surgery was 84 minutes (22mn - 130mn). Six cases of operating incidents were recorded (1 case of accidental injury of a left hepatic artery and 5 esophagal perforations). Conversion to laparotomy was required in 12 cases (7.4%). The delay of oral feeding varied between 1 and 4 days with an average of 2.5 days. Postoperative courses were uneventful in 152 patients (93.8%). Nine postoperative complications were found: gastroparesis (4 patients), postoperative peritonitis (1 case), and dysphagia (4 patients). A death was noted in 1 case by postoperative peritonitis secondary to sepsis. The mean hospital stay was 7 days with extremes ranging from 3 to 10 days.

Keywords: Laparoscopy, Hiatal hernia, Duodenal ulcer complications, Achalasia

Cite this paper: Toure Alpha O. , Foba Mamadou Lassana , Ka Ousmane , Cisse Mamadou , Konate Ibrahima , Dieng Madieng , Toure Cheikh T. , Laparoscopy in Upper Gastro-Intestinal non Tumoral Pathologies: Our Experience in a Low Income Country, International Journal of Surgical Research, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2015, pp. 11-14. doi: 10.5923/j.surgery.20150402.01.

1. Introduction

- Laparoscopic surgery implants itself increasingly in the treatment of digestive diseases in our sub-Saharan countries despite our limited means [1]. Thus, after cholecystectomy, indications extend to upper gastro-intestinal (UGI) tract diseases such as progressive complications of duodenal ulcer and certain disorders of the cardia. The aim of our study was to evaluate the contribution of laparoscopy in non-tumoral UGI diseases in our working conditions.

2. Patients and Methods

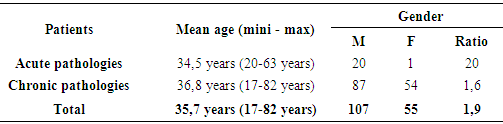

- This was a retrospective descriptive study in General Surgery Service of the University Hospital Le Dantec in Dakar on a period of 10 years (January 2003 to January 2013). We included all patients treated by laparoscopy for acute or chronic UGI disease. Thus, we collected 162 cases. Epidemiological data on patients were listed in Table 1.

|

3. Results

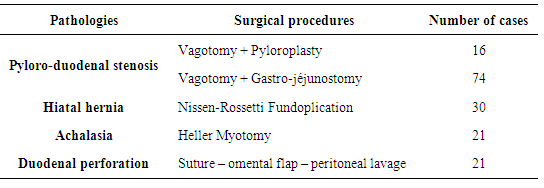

- The pathologies encountered were:- Hiatal hernia with gastroesophageal reflux rebel to medical treatment in 18.5% of cases (n = 30);- Achalasia in 13% of cases (n = 21);- Ulcerative pyloroduodenal stenosis in 55.5% of cases (n = 90);- Perforated duodenal ulcer in 13% of cases (n = 21).All patients with pyloroduodenal stenosis underwent truncal vagotomy performed laparoscopically. Gastric bypass consisted of a gastro-jejunostomy through a mini median laparotomy or pyloroplasty by a right mini-subcostal incision. Indications for surgery were detailed in Table 2.

|

4. Discussion

- Our indications of laparoscopic surgery in non-tumor UGI diseases are dominated by progressive complications of duodenal ulcer such as pyloric stenosis and perforation of duodenal ulcer which constitute 68.5% of our indications. Outside the duodenal ulcer perforation or gastrointestinal bleeding associated with the use of anti-inflammatory, such complications, especially the pyloric stenosis, have become rare in Western countries because of early diagnosis and access to eradication treatment of Helicobacter pylori, a frequency with which stenosis is less than 8.5% [2, 3]. Contrary to the trend observed in developed countries, ulcer pyloric stenosis is still common in developing countries. Indeed it represents 50 to 80% of all complications of ulcer disease [4, 5]. Hiatal hernia, which represent our second indication, constitute only 13% of our series. This low rate is explained by the fact that the surgical treatment of symptomatic hiatal hernia is conceivable only in case of of medical treatment failure [4]. Our 3rd indication of laparoscopic surgery for UGI diseases is represented by achalasia (12.4%). It is rarely encountered in our context. This is explained by the very low incidence of about 1/100000 / year [6].Ulcerative pyloric stenosis is, in our practice, the first evolution complication of ulcer. The truncal vagotomy associated with gastric bypass is the intervention that we master and practice the most for several years because less mutilating than partial gastrectomy and more feasible that the supra-selective vagotomy [7, 8]. The limit we observe for a fully conducted laparoscopic procedure is the cost of endoscopic staplers and long duration of a possible manual laparoscopic gastrointestinal anastomosis.Laparoscopy can confirm the diagnosis of peritonitis and clarify its cause. It must treat ulcer perforation and ensure adequate peritoneal toilet. Different techniques are available to treat perforation: simple suture, suture associated with omental flap, suture combined with vagotomy and pyloroplasty or application of biological glue [9]. In our practice, we perform a simple suture associated with omental flap and peritoneal lavage. Some authors systematically perform the surgical treatment of the ulcer. But recent publications question this surgery over peritonitis [2, 9, 10, 11, 12].Surgical treatment for symptomatic hiatal hernia is understandable therefore that there is a failure of medical and dietetic treatment, and especially to avoid lifetime medical treatment. [13] The introduction of laparoscopy is relatively new in our practice. Our motivation stems from the observation that the Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication formerly performed by laparotomy is perfectly reproducible by laparoscopy at the cost of lower parietal trauma [14, 15]. Persistent dysphagia occurs in 1-3% of cases in multicentric series. Non-randomized comparative series have suggested that the intervention of Nissen-Rossetti (total fundoplication without division of short vessels) is significantly associated with a higher incidence of dysphagia but the only randomized study evaluating the influence of the short vessels section, including a small number of patients, has not confirmed this difference. Iterative endoscopic dilatations are sometimes necessary with a failure rate ranging from 36 to 50% [8].The laparoscopic approach is standardized in our service for the management of achalasia, however, rarely encountered in our practice [13]. In our study, Heller myotomy was performed 21 times. She is the most appropriate method regarding the recurrence rate of 40% for patients treated with non-surgical methods [13, 16, 17]. The mini-invasive approach has enabled a reduction in morbidity, length of hospital stay and return time to normal activity, with improved symptoms rated as good or excellent in 94% of treated patients. Rare cases of intraoperative incidents such as esophageal perforations may justify a conversion [18]. But in most cases, they manage to be sutured laparoscopically.We noted low laparoscopic conversion rate of 7.4%. In the UGI surgery, the study of Coelho reveals that conversion rate from 8% for the first 100 patients to 2% after 492 patients is related to the sample size and the learning curve [19]. Conversion causes are usually represented by adhesions, hemorrhage, hypertrophy of the left hepatic lobe, perforation of the esophagus and technical problems related to laparoscopic equipment inherent to laparoscopic surgery in our conditions of exercise [19]. In the surgery of duodenal ulcer, major conversion factors reported in the literature are the technical difficulties, large ulcers (6-10 mm according to Guirat and Kafih), the occurrence of intraoperative complications, and ulcers friable banks [10, 11].In our study we found nine cases of post-operative complications. In the Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication, persistent dysphagia after surgery could be avoided by carrying out a wide retroesophageal window and making a valve whose height would not exceed 2 to 3 cm. This explains our persistent dysphagia endoscopic dilation rate of 13.3% which is different from 3% of Coelho’s Series whose size is more important [19]. Sledzianovski et al conclude that calibrating the hiatus at the time of the closure of the diaphragmatic pillars reduced the length of immediate postoperative dysphagia and decreases the risk of persistent dysphagia by over-tightening pillar [20]. In truncal vagotomy associated with assisted laparoscopic gastric bypass, gastroparesis on pyloroplasty, which influences our morbidity, is related to poor therapeutic indication at the beginning of the series. Indeed, we were stubborn by a physiological gastric drainage, we went beyond the recommendations that indicate the gastrojejunostomy when the pylorus is very sclerosis inflammatory or when gastric dilatation is greater [6, 21, 22, 23]. The morbidity of laparoscopic surgery in ulcer perforation varies between 6 to 18% in Western series. These rates are lower than those of laparotomy as regards the wound infections and respiratory infections [11]. In our series, the morbidity rate is 2 cases or 10%. We noted no parietal complication. The main morbidity factors of surgery laparoscopic perforated duodenal ulcer are: advanced age (over 70 years), subjects with visceral defects (ASA III and IV) initial shock of the condition and the inexperience of the surgeon [10, 11, 12, 24]. A single case of mortality was objectified by postoperative peritonitis after a suture of peptic ulcer perforation. The postoperative mortality after laparoscopy is lower than 10% [25]. The reported mortality factors are mainly advanced age, the faults, the state of preoperative shock, the occurrence of complications and late response time (over 24 hours) [11, 12]. The deaths we recorded occurred early in our series and was due to bad ulcer suturing.The mean time of oral feeding was 2.5 days, with extremes of 1 and 4 days. This early feeding time determines the resumption of transit. It is one of the benefits of laparoscopy [15, 26, 27].The overall mean hospital stay was 7 days with extremes of 3 and 10 days in our study. In the Nissen-Rossetti fundoplication by laparoscopy, the average hospital stay in our series is similar to Capelluto is 3.2 days [28]. It must nevertheless admit that this hospital stay can be shorter when we will overcome the fear of the immediate postoperative dysphagia which disappears spontaneously. The duration of hospitalization of our patients who underwent truncal vagotomy associated with gastric drainage was 7.3 days. That can seem long compared to 5,4 to 6 days described by the authors [7, 9]. It is explained by the maintaining of the gastric tube after surgery for 5 days to reduce the risk of occurrence of gastroparesis.

5. Conclusions

- Laparoscopy is feasible in our context of developing countries characterized by the technical sub-equipment. His influence on the therapeutic strategy of non-tumoral UGI diseases, in terms of reducing the surgery time, make it a major tool for these pathologies treatment. The short post-operative disability and rapid reintegration allow a reduction of the cost of health care. The adaptation of operative techniques to our conditions provides us with a challenge to keep practicing laparoscopy.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML