-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Surgical Research

2014; 3(1): 7-14

doi:10.5923/j.surgery.20140301.02

The Anatomical Basis for Autonomic Dysfunction in Surgical Coloproctology

Elroy Patrick Weledji1, Divine Eyongeta2

1Anatomy and clinical surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, Cameroon

2Urology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, Cameroon

Correspondence to: Elroy Patrick Weledji, Anatomy and clinical surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Operative neural damage in pelvic and perineal surgery may affect bladder or sexual function, with retention of urine or impotence. Better understanding of the anatomy and physiology of urinary and sexual function together with refinement of surgery for both benign and malignant pelvic and perineal disease has led to a decrease in the incidence of urogenital dysfunction. This paper reviewed the anatomical basis of autonomic dysfunction during pelvic and perineal surgery.

Keywords: Pelvic anatomy, Total mesorectal excision (TME), Autonomic dysfunction, Coloproctology

Cite this paper: Elroy Patrick Weledji, Divine Eyongeta, The Anatomical Basis for Autonomic Dysfunction in Surgical Coloproctology, International Journal of Surgical Research, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2014, pp. 7-14. doi: 10.5923/j.surgery.20140301.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Urogenital dysfunction remain a common problem after rectal cancer treatment with more than half of patients experiencing a deterioration in sexual function, consisting of ejaculatory problems and impotence in men and vaginal dryness and dyspareunia in women.[1] Urinary dysfunction occurs in a third of patients treated for rectal cancer and surgical nerve damage is the main cause. Radiotherapy seem to have a role in the development of sexual dysfunction without affecting urinary function.[1,2] Pelvic autonomic nerves are especially at risk in cases of low rectal cancer and during abdomino-perineal resection.[3] The concept of total mesorectal excision (TME) in rectal cancer whereby the autonomic pelvic nerves in close contact to the visceral pelvic fascia that surrounds the mesorectum (fascia propia) is freed and dropped back has led to a substantial improvement of autonomic pelvic nerve preservation. TME with pelvic autonomic nerve preservation showed relative safety in preserving sexual and voiding function using the international prostate symptom score and international index of erectile function.[4] While severe urinary dysfunction is rare, sexual impairment remains a serious concern after rectal resection with TME.[5] It reduces the problem of accidental bladder denervation from 50-60% with conventional rectal cancer surgery to <20% with TME and the problem of postoperative impotence from 70- 100% to < 30%.[6,7] Acute urinary retention is a common post operative complication following surgery on benign anorectal diseases and increases hospital stay.[8,9] The incidence of post operative urinary retention after anorectal surgery is 15% (range 1- 52%).[9] It is most common after haemorrhoidectomy and a 30% incidence after lateral internal sphincterotomy.[10] Gender-specific pathologies such as benign prostatic hyperplasia among others give a higher incidence of post-operative urinary retention in males (4.7%) than in women (2.9%).[10] The risk increasing by 2.5 times in patients over 50yr of age due to age – related progressive neuronal degeneration leading to bladder dysfunction.[9,10] The incidence of post operative urinary retention varies with the type of surgery; general surgical procedures (~3.8%), hip joint arthroplasty (~ 10.7-84%), and after hernia repair (5.9%-38%).[10] Sexual problems in women after rectal surgery seem to be predominantly due to a local mechanical problem. However, the pelvic autonomic nerves supply the blood vessels of the female internal genitalia and are involved in the neural control of the lubrication and swelling response.[1,11]

2. Anatomy

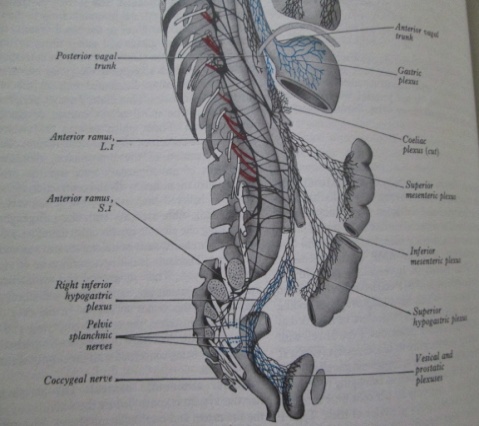

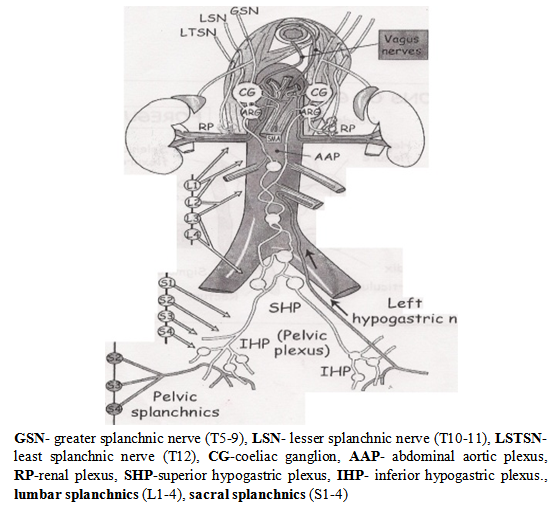

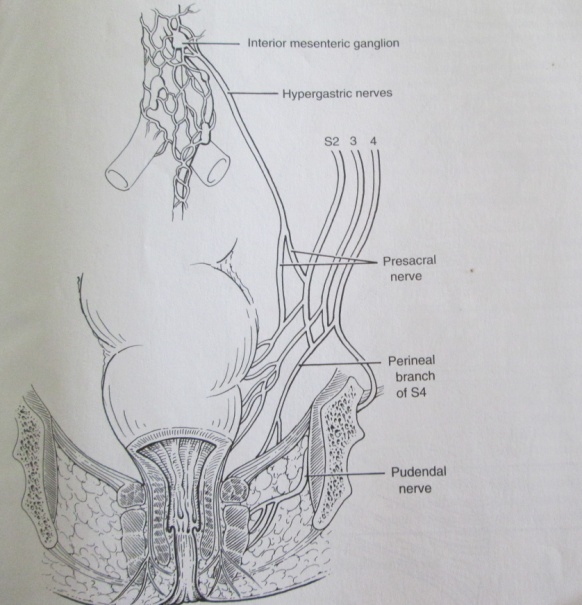

- The bladder and genital tract are supplied by autonomic nerves that are in close relationship with the rectum and for this reason are at risk during rectal mobilization. The sympathetic nerves (thoracic splanchnic nerves) arises from both sides of the thoracic spinal cord (T5-T12), pierce the diaphragmatic crura, flow down in front of the aorta and the root of the mesentery and enter the pelvis in front of the promontory of the sacrum as the hypogastric nerves. These pre-aortic nerves turn just beyond the aortic bifurcation into the superior hypogastric pelvic plexus of nerves. The sympathetic nerves are strengthened by the lumbar and sacral sympathetic nerves as they descend down the abdomen into the pelvis. They divide into two trunks, which pass to form the pelvic plexus on the side wall of the pelvis (the inferior hypogastric plexus) to be distributed to the pelvic organs by branches passing with the blood vessels or with the parasympathetic nervi erigentes (pelvic splanchnic nerves) arising from the sacral segments (S2, S3, S4 ) of the spinal cord. The parasympathetic supply are more difficult to see as it is situated deep in the pelvis and distributed to the pelvic organs in the endopelvic fascia on the surface of the pelvic floor.[Figs.1,2.] The autonomic fibres penetrate levator ani and the perineal membrane to supply the deep and superficial perineal spaces, and the parasympathetic fibres have the independent function of stimulating erection of the penis/clitoris.[fig.3][12,13]

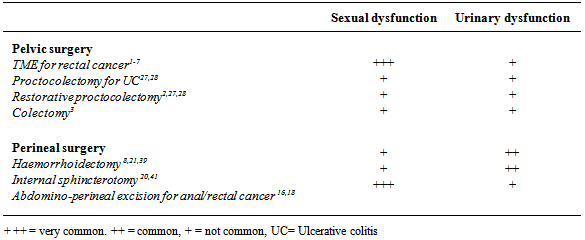

| Figure 1. The right sympathetic trunk and its connexionswith the abdominal and pelvic plexuses |

| Figure 2. Schematic diagram of the abdominal autonomic nervous system13 |

| Figure 3. schematic diagram of autonomic (sympathetic and parasympathetic) innervations of rectum and anal canal |

3. Physiology

- Normal voiding needs a co-ordinated, sustained smooth muscle bladder contraction of adequate size and duration. It needs a decrease in resistance of the bladder neck and urethra and an absence of obstruction. The nervous control of bladder and urethra is rather a complex matter. The sensory component of the sympathetic fibres carry sensation for pain and strong bladder fullness from the sensitive trigone and peritoneum over the bladder towards the sympathetic chain in the least splanchnic nerve (T12). The motor component inhibits the bladder wall itself and act on the parasympathetic ganglion with its inhibitory fibres. The sympathetic fibres also have the independent function of stimulating ejaculation and contracting the bladder neck during that process to prevent retrograde ejaculation in the male.[13,14] The parasympathetic sensory fibres to the bladder wall detects mild fullness but the main parasympathetic motor supply to the wall comes from the parasympathetic outflow in the sacral region- 2,3,4 . They synapse in peripheral ganglia and then supply the bladder wall with the post synaptic fibres. There are also some parasympathetic motor inhibitory fibres acting directly on the ganglia. The somatic inhibitory fibres of the pudendal nerve (S 2,3,4) act on both the pelvic floor and the external urethral sphincter either voluntarily or because of an overfull bladder to allow a drop in the urethral pressure during voiding[fig.3].[14,15]

4. Aetiology and Pathophysiology

4.1. Atonic Bladder

- The major problem with the bladder after pelvic surgery is retention of urine. In older men this may be due to a mechanical obstruction from prostatic hyperplasia causing difficulty in voiding and the exhausted poor bladder muscle’s inability to push to order, or, it may have been caused by injury to the motor parasympathetic nerves to the bladder detrusor muscle, leading to an atonic bladder.[16-19] Direct damage to the nerves innervating the lower urinary tract in a previous pelvic surgery is a risk factor.[19] It may be clinically apparent which of these causes is the most likely, but urodynamic investigation will demonstrate the difference between obstruction and atonia.[15,18] If the cause is prostatic hyperplasia, then a transurethral prostatatectomy can be performed but if the cause is atonia, then a period of some weeks of catheterization will often allow the bladder to recover tone and permit adequate voiding. It is interesting to note that in one study urinary obstructive symptoms were not risk factors for post operative urinary retention following anorectal surgery which suggests a multifactorial aetiology. [8] One theory is that injury to the pelvic parasympathetic nerves (pelvic splanchnic-S2-4) and pain carried by the somatic sensory A δ and C fibres of the pudendal nerve (S2-4) evoke a sympathetic reflex increase in tone of the bladder neck (internal urethral) sphincter.[10] The other theory is that the parasympathetically- innervated bladder detrusor muscle is being inhibited by bladder overfilling, precipitated by the effect of general anaesthesia on bladder function.[20,21] Perioperative fluid restriction and adequate pain relief appear to be effective in preventing urinary retention in a significant number of patients after anorectal surgery.[10] Thus, the importance of perioperative catheterization that leaves an empty bladder.[22,23] In patients undergoing hernia surgery and anorectal surgery intravenous administration of more than 750 mls of fluids during the perioperative period increased the risk by 2-3 times compared to other surgeries.[9] Excessive infusion of intravenous fluids can lead to over distension of the bladder, especially in patients under spinal anaesthesia whose bladder filling perception is abolished.[9,10,16] It is also known that over- distension inhibits detrusor function and the normal micturition reflex would not be restored even after emptying the urinary bladder with a catheter. The fact that bladder volume greater than 270ml represents a risk factor for post operative retention may explain why a prolonged duration of surgery, is also a risk factor.[9,10] General anaesthetic agents cause bladder atony by interfering with the autonomic nervous system.[10] Ketamine has less effect on the autonomic nervous system than the standard anaesthetic agents.[23,24] Spinal local anaesthetics act on the neurons of the sacral spinal cord segments (S2,3,4) and by blocking afferent and efferent nerve conduction from and to the bladder may cause bladder atony.[25] Systemic opioids both by intravenous and intramuscular routes inhibit the release of acetycholine from the parasympathetic sacral neurons that control detrusor contractility and also increase the incidence of acute urinary retention.[26] This is because the axons of preganglionic parasympathetic fibres contain enkephalins that are transported to the parasympathetic ganglia and have an inhibitory modulating effect on the release of acetylcholine that cause detrusor contraction.[14]

4.2. Bladder Neck Sympathetic Tone

- Post operative pain, rectal distension and anal dilatation increase bladder neck sympathetic tone through a sympathetic reflex with the afferents being the somatic and visceral sensory nerves.[13-15] In either sex the sympathetic response to pain may lead to abnormal sphincteric activity causing difficulty in voiding and thence urinary retention. Disease severity, amount of analgesia required, simultaneous operations i.e. sphincterotomy, haemorrhoidectomy, fistulotomy, incision and drainage of abscess etc, were risk factors of post operative urinary retention.[8-10] An inserted haemostatic anal pack usually cause post operative pain and thus the insertion of an indwelling urinary catheter for 24 hours may avoid acute urinary retention.[21] In the neuropathic bladder where the sphincters does not synchronously relax detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia), the bladder cannot empty properly. The most common form is seen in middle-aged men, where the α-adrenergic fibres of the bladder neck fail to relax and can be successfully treated with α-blockers or the fibres may be divided by transurethral incision of the bladder neck. When it is the striated muscle component of the sphincter that fails to relax, the diagnosis can be confirmed by electromyography of the levator ani muscle which will show the action potentials continuing loudly when they ought to be electrical silence. Sometimes listening to the noise of the action potentials on a loudspeaker enables the patient to inhibit them herself i.e. biofeedback.[15]

5. Surgical Implications

5.1. Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Since the presacral nerves are situated well posterior or lateral to the rectum, it should not be difficult to avoid damage when operating for inflammatory bowel disease as the dissection stays close to the rectum. As the lateral ligaments are divided close to the rectum in inflammatory bowel disease bladder and sexual dysfunction is kept to a minimum. Impotence is rare after rectal excision for inflammatory bowel disease and fashioning of ileo-anal pouch but cases of retrograde ejaculation have been recorded. [2,27] Although the risk of impotence is low, warnings are vital as these patients are often young , and impotence will be a particularly severe disaster. Some women have dyspareunia (pain on sexual intercourse) after rectal excision due to the vaginal vault falling back to the sacrum. Dyspareunia has been reported in 7 to 28% of females after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis.[27] This can be prevented or minimized by transporting the omentum or other tissue into the area infront of the rectum.

5.2. Total Mesorectal Excision (TME) for Rectal Cancer

- It may, however, be much more difficult to avoid pelvic nerve injury in cases of malignant disease when a more radical total mesorectal excision (TME) approach for rectal cancer is taken.[2] This entails the en bloc excision of the total mass of perirectal lymphatic and fatty tissue down to the pelvic floor. Impotence is reported in many patients after rectal excision for cancer.[1-7,26] Damage to the parasympathetic nerves are more likely as they lie close to the lateral aspect of the lateral ligaments of the rectum postero-laterally to the bladder and are at risk of damage by wide excision of the lateral ligaments.[2,12,13] The learning curve in the TME procedure plays a major role with respect to autonomic nerve preservation.[30] Laparoscopic approach for TME allows similarly favourable results with regards to postoperative urogenital function at best for tumours situated in the middle and upper third of rectum, compared with open surgery.[5]

5.2.1. Finding the Correct Plane

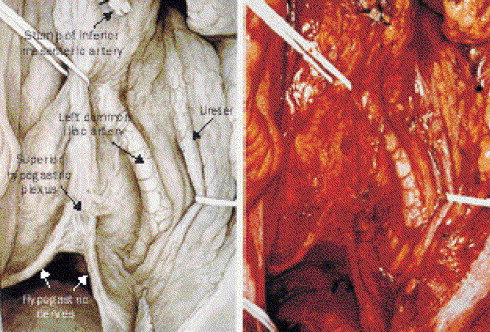

- This is done by finding the plane behind the root of the ‘pedicle package’, that is the root of the hind gut mesentery. [29,30] This visceral structure is carefully dissected away from the parietal structures of the posterior abdominal wall. The inferior mesenteric artery is ligated about 1-2cm from the aorta itself, just far enough forward to preserve the pre-aortic sympathetic nerve mini-trunks. The main sympathetic trunks are further back, but the mini-trunks on the front are still very much worth preserving. The plane is most readily reviewed by looking at the things which cross it. These include the left common artery, the gonadal vessels, the ureter and most subtly the superior hypogastric plexus of sympathetic nerves. Stripping the plexus off the aorta as part of lympho-vascular (oncological) clearance adds nothing to the cure of the cancer but does mean that the patient loses the ability to ejaculate and in various other subtle ways his autonomic nerve function is impaired. Nerve preservation in principle does not compromise resectability unless infiltrated with tumour.[31] Finding a plane in front of these nerves, in a circumferential sense will lead down into the correct plane in the pelvis called the ‘Holy Plane’.[30,31] This plane is between the mesorectum, the integral visceral mesentery of the hind gut and the surrounding nerves on which sexual function depends. The sympathetic nerves and the parasympathetic nerves, which are the parasympathetic outflow, coming forward from the front of the sacral plexus, have all got to be dissected off the periphery of the mesorectum without tearing or damaging the mesorectum. [32,33] There is a reported 95% efficacy of a nerve stimulator that enhances autonomic nerve identification and preservation during TME.[34]

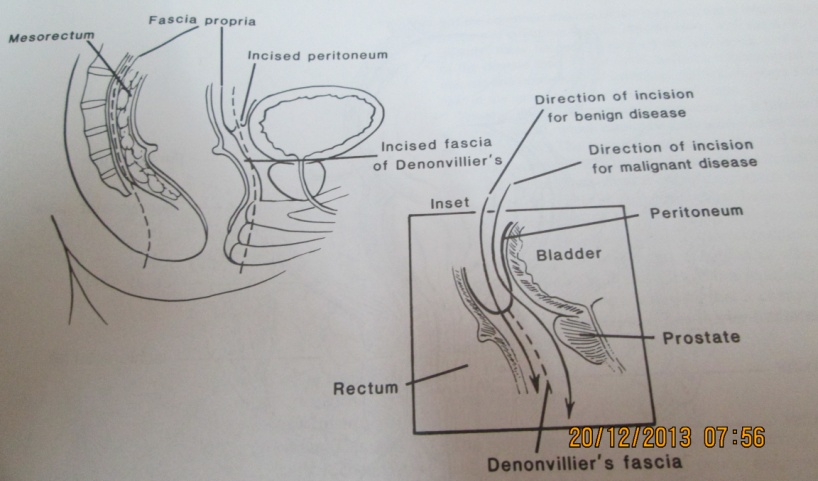

5.2.2. Dissecting the Holy Plane

- This is generally easiest done at the back, by first identifying the two superior hypogastric nerves that come from the superior hypogastric plexus and run down the pelvic side wall (Fig.4). Using St Mark’s retractor the mesorectum is lifted forward and the nearly avascular cleavage plane around the lateral pelvic wall developed to a point of adherence between the mesorectum and the inferior hypogastric plexuses low down laterally on the pelvic wall. These are were the parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves meet often called the lateral ligaments which links the prerectal and retrorectal parts of the field of dissection.[2,12] Traditionally surgeons at this point have tapered into the mesorectum, clamped and cut with consequent bleeding. This might be avoided by cutting at the adherence slightly inside the point where they swing away from the parietal fascia at the site of the planned rectal excision. Thus, cutting the nervi erigentes that innervate only that aspect of the rectum which is being excised.[29,30] In the anterior dissection, incorporating the peritoneal reflection as part of the specimen creates a dissection plane (cul-de-sac) behind the top and back of the seminal vesicles that goes down onto the fascia of Denonvillier. Although the antero-lateral lying neurovascular bundles that supply the seminal vesicles may be injured, this is extremely unusual owing to the presence of Denonvilliers’ fascia.[35]. This white fascia layer is useful because it is fairly firmly stuck to the anterior mesorectal fat and closely applied to the prostate than the rectum. It lies just anterior to the fascia propria and gives the proper plane of dissection that would lead down to its adherence to the back of the prostate (Fig.5).[36] By not excising Denonvilliers’ fascia postoperative sexual dysfunction can be minimized without compromising the oncological outcome of surgery. A ‘U’ shape incision on Denonvilliers’ fascia may also prevent damage to the antero-lateral nerves.[30,35] This is a difficult and challenging part of the dissection in low rectal tumours with regard to avoiding damage to the back of the prostate and consequent bleeding.[35] Bladder injury may occur during rectal excision for an adherent rectal carcinoma. An incidence of 2% is reported.[2] The area at most risk is low down on the posterior bladder wall or trigone. It is desirable to open the bladder in difficult dissections so that the orientation becomes easier and an injury to the trigone is avoided. It is easy to close the fundus, but closing the trigone and bladder base are difficult because of the proximity of the distal ureters.[2,13] A very low local recurrence rates (4-5%) have been reported after TME with autonomic nerve preservation.[32] Although the autonomic nerve preservation technique minimized urinary dysfunction, sexual function particularly ejaculation was often damaged after an associated radical pelvic lateral node dissection. [36,37]

| Figure 4. Intraoperative view of the superior hypogastric plexus and hypogastric nerves after total mesorectal excision with nerve preservation. (with permission)31 |

| Figure 5. Schematic diagrams of the mesorectal and anterior dissection planes |

5.3. Perineal Surgery

- Acute urinary retention is common following anorectal surgery for various reasons as mentioned above.[38] Anxiety is thought of as a risk factor but the use of an anxiolytic agent is not effective in the treatment of postoperative urinary retention.[10] However, the parasympathomimetic agent, bethanechol, in a dose of 10 mg subcutaneously, significantly lowers the incidence of postoperative urinary catheterization and should be considered as initial treatment of postoperative urinary retention following anorectal surgery.[39,40] It seldom works on the detrusor that is exhausted by obstruction or rendered unstable from whatever cause.[10] Further studies would establish the role of α-antagonists in the prevention of post operative urinary retention among patients undergoing anorectal surgery.[41]Post operative urinary retention in ambulatory surgery (low risk patients) is usually treated with in-out catheterization, but for anorectal surgery most authors suggest 5 days with a range between 3-10 days.[42,43] The incidence of urinary tract infection after anorectal surgery and 5 days of catheterization ranges between 42% and 60%, thus the need for good sterile technique at urethral catheterization and prophylactic antibiotics.[44] For major complicated surgery and with extensive perineal and rectal dissection, bladder catheterization is required for a longer period of time according to clinical conditions.[45]

|

|

6. Conclusions

- Structured education of surgeons with regard to pelvic neuroanatomy and systemic registration of identified nerves intra-operatively may improve functional outcome of patients undergoing pelvic surgery. Pelvic nerve injury is best avoided by identification and preservation of the sympathetic nerves early in the operation. Patients undergoing pelvic and perineal surgery should be informed of all associated risks pre-operatively and ideally the at-risk patients should have their functional status evaluated before and after surgery. Further research is required to determine the effects of adjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancer on sexual function. Since postoperative urinary retention after anorectal surgery is common, it makes sense to routinely catheterize the high risk patients preoperatively. This would prevent post operative urinary retention until normal bladder function returns.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML