-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Statistics and Applications

p-ISSN: 2168-5193 e-ISSN: 2168-5215

2024; 14(2): 22-34

doi:10.5923/j.statistics.20241402.02

Received: Mar. 23, 2024; Accepted: Apr. 8, 2024; Published: Apr. 10, 2024

Too Starved to Live: A Statistical Analysis to Explain the Karamoja Region

Victoria Kakooza, Richard Awichi, Ainomugisha Smartson

Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Faculty of Science, Kyambogo University, Kampala, Uganda

Correspondence to: Victoria Kakooza, Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Faculty of Science, Kyambogo University, Kampala, Uganda.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

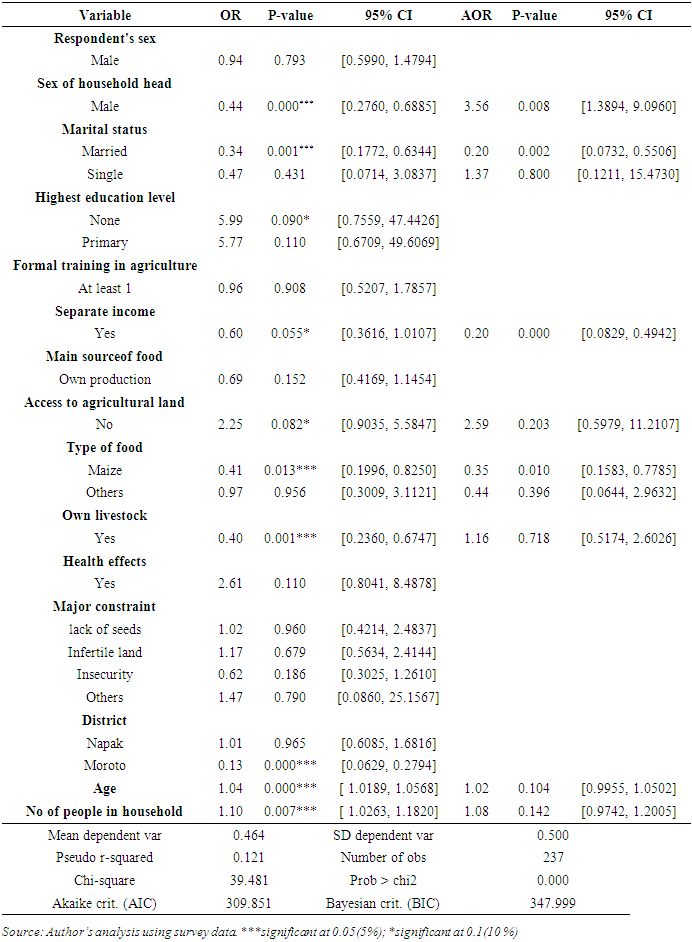

The study brings an understanding of the consistent starvation in Karamoja with a focus that starts from the environment to the individual. Climate-resilient agriculture, sustainable pastoralist practices has been adopted to help avert the challenges from the rough climate and pastoralism. However, the persistence of starvation requires a new understanding of the underlying causes of starvation, which implies that if we are to address the problem of starvation in Karamoja, it requires a holistic approach that consists of individual factors in combination with other factors. The novel of this study was about the nexus of individual characteristics and starvation in the region of Karamoja, Uganda. A logistic regression model was used for the analysis. The determinants of starvation in Karamoja were sex of household head, marital status, type of food grown(maize),owning livestock, staying in Moroto district, age and the number of people in household; were all found to be significant at 5% (p<0.5). In addition, having no education level, a separate income and no access to agricultural land were all sign at 10% (p<0.10). A turnaround purposed the need to focus on human development and concentrate to help the women headed households so as to go an extra mile. The solution that would therefore nail it, is one that has a holistic approach.

Keywords: Karamoja, Starvation, Logistic regression model

Cite this paper: Victoria Kakooza, Richard Awichi, Ainomugisha Smartson, Too Starved to Live: A Statistical Analysis to Explain the Karamoja Region, International Journal of Statistics and Applications, Vol. 14 No. 2, 2024, pp. 22-34. doi: 10.5923/j.statistics.20241402.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Globally, extreme hunger and starvation undoubtedly continues to typically impose great threats on local communities. According to the World Food Strategic Plan, up to 811 million people have been classified as chronically hungry. About 283 million people were estimated to be in specific need of food relief in the year 2021,which comprised of 45 million people worldwide at emergency level of acute hunger and a half million people that suffered from famine-like conditions (Segate, 2020). Uganda as a whole has been said to be grappling with severe food unavailability. Some actually have made a public outcry for international help to save the starving Uganda (Doces, 2014). Despite that Uganda’s poverty and starvation is reducing as a whole, every district has been unique. Some regions and people are yet excluded from such optimistic trends. Starvation is greatly a part of day to-day lives of some Ugandans. Karamoja region is one of the regions that has suffered from starvation. It was recently reported that at least 2,207 deaths were registered in Karamoja as a result of starvation or starvation relate illnesses in 2022. Kotido, Kaabong, Moroto and Napak registered the most numbers with deaths of 1676, 225, 166, 125 respectively (Sserugo, 2023). Hence, many people turned to leaves as a source of food (Owiny, 2023) and more than 2000 children were left malnourished (Kaggwa, 2023).Starvation in Karamoja has been a long-standing problem (Mamdani, 1982; Gartrell, 1985). Barber (1962) further reports that in the 1890's the region of Karamoja suffered from a series of cattle diseases, which led many Karamojong to flee, others resorted to hunting as a coping mechanism to live and others died of starvation. It is noted that previously in the colonial rule Karamoja region was documented as a long-grass savanna that later turned into a short grass savanna, with some places that were barren or with a dry bush-land. (Mamdani, 1982; 1986; Gartrell, 1985; De Haas, 2020). It is worth noting that this region is said to be capable of being an agricultural food hub (Wang, 2013). This could be after the long periods of de-pastoralisation as a form of livelihoods diversification and changing identities (Meyerson, 2023); which are taking root in Karamoja (Caravani, 2019). Other endowments are minerals like gold, which the Karamojong have embraced. These gold mining activities have offered an opportunity for increased income (Serwajja & Mukwaya, 2020). For the last two decades, the government of Uganda has strongly prioritized ending starvation. Such interventions included: The Poverty Eradication Action Plan (PEAP) in 1997 (MoFPED, 2004); Plan for Modernization of Agriculture and National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS) (MoFPED, 2007); Universal Education (UPE and USE); Prosperity for All program ‘Bona Bagagawale’ and introduction of Savings and Credit Cooperative Organizations (SACCOs) (MoFPED, 2007). Recently, there has been emergency help from the government, various organisations and private individuals, which have offered support inform of food relief, medical supplies, and other form of aid. Despite the fact that the aid has positively impacted the communities, the reproduction of starvation in this region is a clear indicator that they have not succeeded to treat the root cause of the problem but have only stopped at symptoms.However, Karamoja is still starving even after all these thirty years (Studebaker, 2021). The dynamics and persistence of starvation in this area over a long period of time suggests that the core issue is not yet tackled. Currently, the paradox of a starving people amidst so much investments and attention leaves many baffled and in dilemma. The present plight experienced in Karamoja has its origin in this deterioration, systematically destroying pastoralism through overgrazing and hence a poor transition into agriculture (Caravani, 2019). Therefore, starvation has taken on different dimensions, levels and effects over the years. Planning and long term solutions to starvation ought to be founded on a solid understanding of the time-specific causes. Nearly half a million people (480,000) are estimated to be experiencing ‘crisis’ (IPC 3+) conditions, including 102,000 in ‘emergency’ (IPC, 2023; World Vision, 2023). It is reported that over half-a-million residents are reported to go for days hungry in Karamoja region (Katumba, 2022). Worse still, 900 children were reported to have died resulting from starvation (Emwawu, 2022). In was stated that there would be acute food insecurity crossing to 2023 in Karamoja (OCHA, 2022). Over 2000 were reported to have died resulting from starvation (Sserugo, 2023; Owiny, 2023; Kaggwa, 2023). This concern of Karamoja region has woken up all stakeholders and researchers to intervene with an intention of coming up with a new, permanent strategy and solution. Otherwise, the vision of zero hunger by 2030 a part of the Sustainable Development Goals (Weiland, 2021); remains a myth in this area. Previous starvation occurrences in Karamoja have been linked to climate harshness, community conflicts and poverty among others, which indicates limited policies and narrowed recommendations expected to relieve this region of future starvation. In addition, the support of food aid has been inadequate (UNICEF, 2023) and seems short term. Literature affirms this kind of support to contribute to the starvation cycle over time. (Boyes-Watson & Bortcosh, 2022). This suggests that there's need for this problem to be addressed permanently.There is an area which hasn’t been handled that includes; individual and household characteristics that dictate and curve the attitudes, resilience, culture and opportunities that are vital to address conflicts, vulnerabilities and access of food. This offers a new interpretation of the starvation problem. The novel of the study is to shed light and uncover the root of the starvation problem in Karamoja. For instance, what would be the explanation of the persistence of these starvation in Karamoja while the rest of Uganda have an improved poverty and food provision? The goal of this study was two-fold firstly, this study explored the local realities and factors that had shaped the recent starvation. Secondly, the study disentangled the influence of gender on starvation in the selected districts of Karamoja.

1.1. Karamoja Region in Uganda

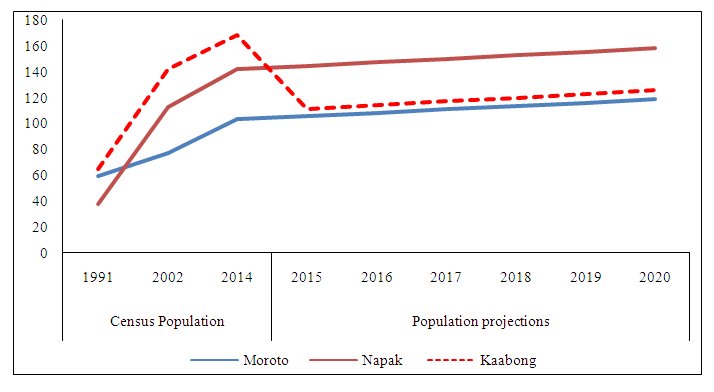

- Karamoja region is located in the north-east side of Uganda, East of Africa, bordering Sudan and Kenya. The region stretches covering an area of 27,528 km2. The Karamoja region consists of nine districts: Abim, Amudat, Kaabong, Karenga, Kotido, Moroto, Nabilatuk, Nakapiripirit and Napak.The region has unique features that make it distinct from other regions in the country. The region's scenic landscapes, cultural practices, and traditional way of life offer unique experiences for visitors. It is important to understand the unique geographical, ethnic, livelihoods and cultural context of Karamoja, because the efforts to promote development and resilience in the region often take into account its unique environmental conditions. Geography and TopographyKaramoja is marked by vast plains, rocky hills, and mountainous areas that contribute to its varied topography. The landscape is rugged, with rocky outcrops scattered across the region. These elevations can influence local weather patterns and water availability.SoilsThe soil is largely sandy, loamy and infertile soils. These lands are overgrazed and the lack of pasture force nomadic movements during the long dry season (September to April), which leads to the competition for scarce resources and thus cau ses to conflict.PopulationKaramoja region has a human population of approximately one million people (UBOS, 2019). The main ethnic groups in Karamoja includes the Karimojong people who are pastoralists, traditionally relying on livestock for their livelihoods. Other smaller ethnic groups, such as the Teso and the Jie, also inhabit the region.The population for all the three districts has continued to grow from 1991 to 2014. Initially the population for Moroto in 1991 was 59,149. The population increased from 77,243 in 2002 to 103,432 in 2014 representing an average annual growth rate of 2.8 percent between 2002 and 2014. The population for Napak increased from 112,697 in 2002 to 142,224 in 2014, an equivalent of 2.1 percent annual growth rate. On the other hand, the population for Kaabong increased from 141,568 in 2002 to 167,879 in 2014 which represents an annual growth rate of 1.5 percent. This is shown in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Population by Census Year (1991-2014) and Population projections ('000s) (Source: UBOS 2024) |

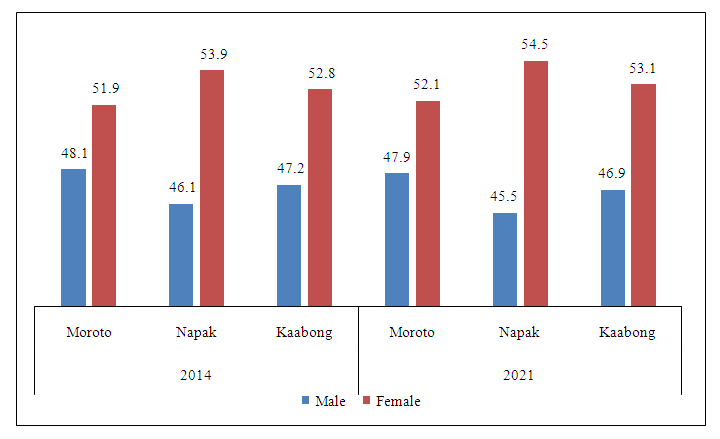

| Figure 2. Sex distribution of the population (%) (Source: UBOS 2024) |

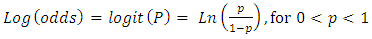

| Figure 3. Household headship (%) (Source: UBOS 2024) |

| Figure 4. Population Pyramid for Moroto, Napak and Kaabong, 2019/20 (Source: UBOS, 2024) |

2. Literature Review

- Starvation is defined as a process that may occur from the long and continuous deprivation of food needed to maintain the normal health (Mahanta & Raktim, 2014). There are two types of starvation, namely, acute and chronic. Acute Starvation is said to result from unexpected and abrupt deprivation of food, while, Chronic Starvation results from gradual. (Mahanta & Raktim, 2014). Biologically, starvation is said to involve deprivation of calories meant to satisfy body demands for energy used for body metabolism (Naik, 2016). Shadrach et al. (2022) adds that starvation involves an extreme intake deficiency of caloric energy that causes an imbalance between existing energy and utilization within the body. In otherwise, starvation is malnutrition and hunger, at their worst levels.Starvation is described to either be voluntary or involuntary (Bassi, 2018). Voluntary Starvation is said to occur when one by choice goes without food over a period of time. This is so, in case of fasting and dieting. Voluntary can also be caused by (Shadrach et al., 2022). Involuntary starvation on the other hand involves body being deprived of food due to food shortage or unavailability. This only study focuses on involuntary starvation. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, death. Causes of Starvation Starvation can result from various causes, often interconnected and contributing to a complex web of factors. Some common causes include:Gender Gender can play a significant role in determining an individual's susceptibility to starvation and their ability to persist through periods of food scarcity. It has not been made explicit whether more men than women were affected by starvation (Bello, 2022). Some studies indicate that gender likely effects hunger (Stryker, 2022). In a study on the impact of gender equity in agriculture on nutritional status, diets, and household food security; found that gender equity in terms of income, land and livestock has heterogeneous associations with household food unavailability. These studies therefore imply a linkage between gender and starvation (Harris-Fry et al., 2020). The findings of Ilukol (2022) also presented women as being very instrumental in enhancing food availability in Napak. This was true in the communities where women engaged in farming, self-employment and sanitation management among others. Climate ChangeChanges in climate patterns, including droughts or floods, can impact agricultural productivity, affecting food availability and contributing to hunger (Alpino et al., 2022; Kawuma et al., 2024). Mordeson and Mathew (2021) in examining the effects of climate change on global hunger, found a link between the two, hence emphasising the vulnerability of countries to climate change. Hansen et al. (2022) confirms that a drop in climate negatively impacts economic accessibility of food. Literature therefore confirms the potential impact of climate change on food provision, risking starvation of the people. This negative impact can be through reduced water necessary for plant, animal and marine life. This in turn leads to decreased agricultural yield.Income and Poverty Income and poverty play a significant role in determining an individual's capacity to endure extended periods of food insecurity and starvation. Poverty and economic instability can limit individuals' purchasing power, hindering their ability to afford an adequate and nutritious diet. (Pathak, 2010; Mahadevan & Hoang, 2016; McCann, 2016; Howe & Naumova, 2022).Disease and EpidemicInfectious diseases can affect crops, livestock, and human populations, disrupting food production and contributing to malnutrition (Tweyongyere et al., 2024; Namuhani et al., 2024; Omadang et al., 2024). Healthy, fat people are said to be able to handle stress better than sick, lean people (Tamilu, 2014). In addition, body temperature is said to be linked to starvation. Being exposed to high temperatures is said to expose one to starvation and hence shorten a person's life (Tamilu, 2014). Literature (Hopp, Clementinah, Verdick, & Napyo, 2022; Mirzeler, 2024); explains disease and epidemics having a significant impact on food security and nutrition, potentially leading to starvation by impacting on economic productivity, disrupting of food systems.Furthermore, epidemics like Covid-19 (Arasio, et al., 2020; Tesfaye, Habte & Minten, 2020; Osendarp et al. 2020; World Bank, 2021); can disrupt food systems, leading to food shortages and price spikes. Quarantines, restrictions on the movement of people, and the closure of markets; can all impact food supply chains. These cause reduced production and agricultural productivity hence decreasing food availability.Political Instability Unstable political environments may hinder effective governance and the implementation of policies to ensure food security. Political unrest can disrupt food distribution systems and exacerbate starvation. Dyson (2018) argued that politics contributed to mass starvation, for instance fewer famines and deaths were noted when politics was good. Moszynski (2008) and Conley et al. (2022) affirmed that starvation was worsened by the effects of war in East Africa and in India, respectively. Age Literature cites a difference between the effect of childhood starvation and adult starvation, hence links age and starvation. (Dong, Du, Wu & Wu, 2021; Shi, & Dong, 2022). Age can also have important implications for an individual's ability to persist through periods of food scarcity and starvation. In a study in Karamoja, Latham (2020) uncovered that younger boys that were all more likely to have famine reinforcement, yet older girls, were more likely to have compensatory effects. From literature, age impacts on starvation persistence by emphasizing the difference in immune systems, vulnerability, body metabolism, resilience as well as access to resources.Lack of EducationInsufficient knowledge about nutrition and agricultural practices may hinder communities from making informed choices to ensure a balanced and sustainable food supply. King (2004) saw educating girls as one of the primary solutions for negative effects arising from the world's increasing population problems. He adds that girl education lowers fertility rate, which is the major detriment to population growth. This was agreed by some other researchers (Datzberger, 2022; Nalumenya, et al., 2023).Population and dependence rateKing (2004) asserts that the long standing effects of an increasing population are the entrapment of the people in direct poverty and starvation; like in Rwanda and Malawi. He calls for an urgent need for population control so that a community does not get trapped in these effects.CultureTraditions and norms in some African countries is said to limit access and ownership of land, income and employment. As such, cultures are cited among factors that influence starvation (Mo et al., 2024).In conclusion, starvation is a complex phenomenon with many factors causing it. Addressing starvation requires a comprehensive approach that considers these interconnected causes and involves efforts to improve agricultural practices, promote economic development, provide humanitarian aid in times of crisis, and implement policies to ensure food security and equitable access to resources.

3. Methodology

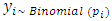

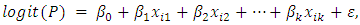

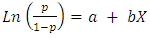

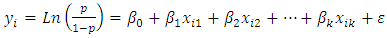

- Statistical modelling of starvation aims to understand and predict the dynamics of food consumption, food availability, and nutritional status within populations, with the ultimate goal of informing policies and programs aimed at reducing the burden of malnutrition. The survey collected data from of Moroto, Kaabong and Napak; which are the worst hit districts in Karamoja sub-region. Each of these three districts will be divided into clusters of sub-counties. Clusters will then be randomly selected from which household random sampling will be conducted. The survey sampled 385 respondents from of the three districts. Data collection involved a systematic process of gathering, recording, and organizing information to address the objective. The study used interview guides to collect data because some of the rural farmers are assumed to be unlearned.The study collected data on: Prevalence of starvation; demographic and socioeconomic Characteristics of the respondents (especially age and education level) per Household; Source of Household Food; gender of the head of the household; access to the market and food aid (distance to the nearest market);This study utilises the Logistic model statistically regresses the explanatory variables and a binary explained variables to predict their relationship. The logistic regression originated far back in the 19th century (Cramer, 2002; Wilson et al., 2015); and has since taken roots in current research studies from small scale data studies Rahmatinejad et al., 2024; Ghosh & Saha, 2024) to large scale data studies (Ming & Yang, 2024). This is because the logistic regression has demonstrated a unique superiority in linearizing relationships pertaining binary dependent variables (Lu, 2024) and for easy implementation (Damayanti, Puspita, & Sundari, 2024).The logistic model (or logit model) is a statistical model that models the log-odds of an event as a linear combination of one or more independent variables. The Logistic regression was applied because of the categorical nature of the dependent variable, which is starvation.

In logistic regression, the dependent variable is a logit, which is the natural log of the odds, that is,

In logistic regression, the dependent variable is a logit, which is the natural log of the odds, that is, Given that in a logistic regression,

Given that in a logistic regression, Then,

Then,

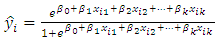

Giving rise to the sigmoid function

Giving rise to the sigmoid function where P is the probability of a 1, e is the base of the natural logarithm base, an exponential function approximately equal to 2.718 and a is the intercept, representing the value of P when X is zero and b representing how quickly the probability adjusts with changing X a single unit. This relationship between X and P is nonlinear.The linear formula relating the independent variables to the dependent variable

where P is the probability of a 1, e is the base of the natural logarithm base, an exponential function approximately equal to 2.718 and a is the intercept, representing the value of P when X is zero and b representing how quickly the probability adjusts with changing X a single unit. This relationship between X and P is nonlinear.The linear formula relating the independent variables to the dependent variable Where

Where  is the probability of the dependent variable. Y is categorical (starvation). We assumed that Y had only two categories that were code 0 and 1;

is the probability of the dependent variable. Y is categorical (starvation). We assumed that Y had only two categories that were code 0 and 1;  are values of the independent variables which were both binary and continuous variables;

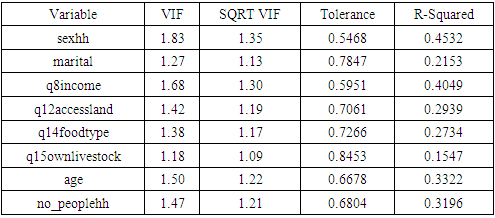

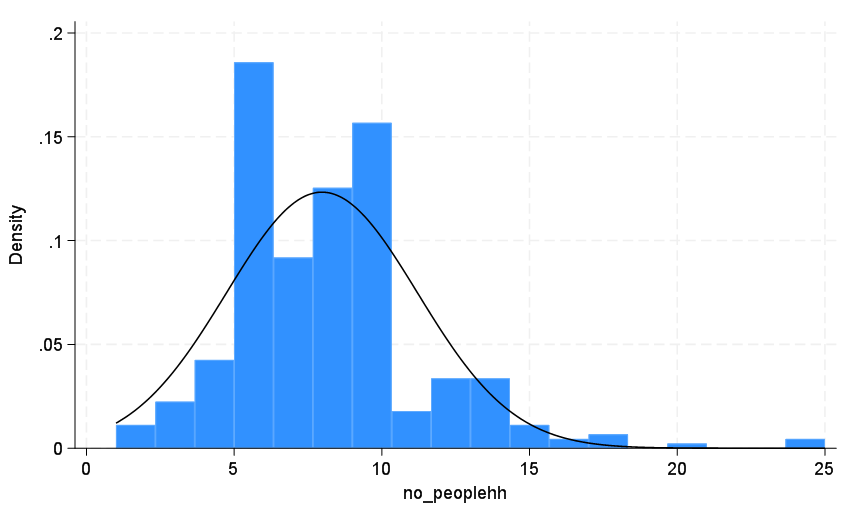

are values of the independent variables which were both binary and continuous variables;  is the error term.Diagnostic tests. Multicollinearity The model assumes that there’s no strong multicollinearity between the independent variables. As such, a check is conducted using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Any cases of violation of this assumption is to be corrected. Goodness of fit The goodness of fit is performed to test the overall significance of the model. The test in logistic regression attempts to get at how well a model fits the data. A likelihood ratio test analogous to the F-test in simple/Multiple linear regression is done. The test employs the following hypotheses:H0: model is exactly correctHA: model is not exactly correctThe residuals are given by

is the error term.Diagnostic tests. Multicollinearity The model assumes that there’s no strong multicollinearity between the independent variables. As such, a check is conducted using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Any cases of violation of this assumption is to be corrected. Goodness of fit The goodness of fit is performed to test the overall significance of the model. The test in logistic regression attempts to get at how well a model fits the data. A likelihood ratio test analogous to the F-test in simple/Multiple linear regression is done. The test employs the following hypotheses:H0: model is exactly correctHA: model is not exactly correctThe residuals are given by  Where

Where  Basing on the above residuals, the Chi-square test was done:The Chi-square test standardizes the residuals as:

Basing on the above residuals, the Chi-square test was done:The Chi-square test standardizes the residuals as: From which a

From which a  statistics as follows:

statistics as follows: with degrees of freedom equal to:

with degrees of freedom equal to: Ethical considerations Ethical considerations were done. Approvals from the Research Ethics committee and National council for science and technology were undertaken. Also informed consent and participant confidentiality were obtained during the data collection phase. The collected data then underwent analysis, leading to meaningful interpretations and conclusions in the research study.

Ethical considerations Ethical considerations were done. Approvals from the Research Ethics committee and National council for science and technology were undertaken. Also informed consent and participant confidentiality were obtained during the data collection phase. The collected data then underwent analysis, leading to meaningful interpretations and conclusions in the research study.4. Empirical Results

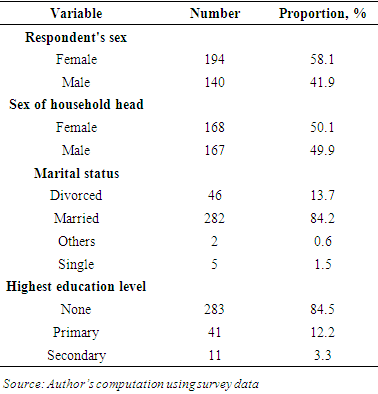

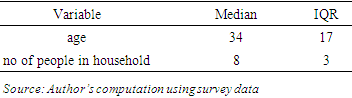

|

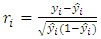

| Figure 5. Histogram for age of the respondent |

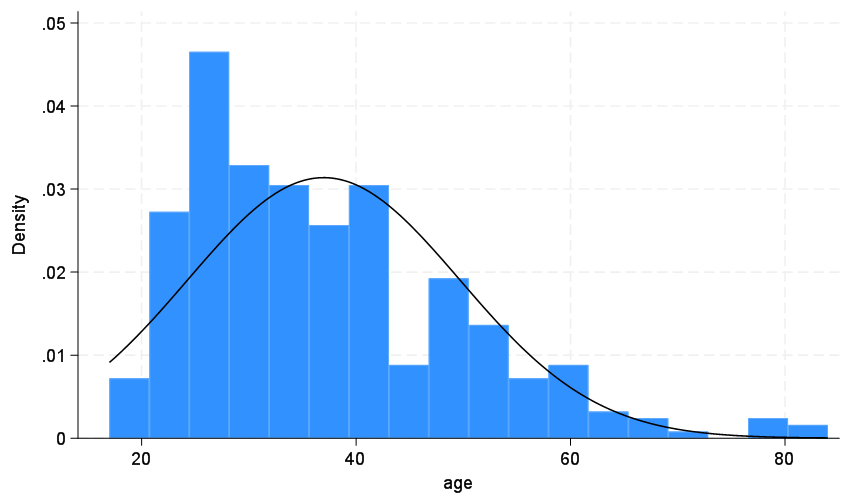

| Figure 6. Histogram of number of people in a household |

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion of Findings

- The study investigated the unexplained component of individual/household characteristics; to understanding factors contributing to starvation in Karamoja region, Uganda. From the findings of the study, these mainly included; sex of household head, marital status, type of food grown(maize),owning livestock, staying in Moroto district, age and the number of people in household; as well as other factors that included; no education level having, a separate income and no access to agricultural land.Even when the Karamojong have pressed on, not giving up, but working hard; a turnaround purposed on human development. This is in line with Wasonga & Arasio, (2023), who reported that the level of illiteracy in Karamoja was found to be so high that some could neither read nor understand information. The findings also agree with Maulana (2023) who cites that building self-actualization would help mend the broken child character. Education therefore can come in handy in helping the Karamojong accept, understand and use information. It would hence enhance a better use of the upgraded agricultural and technological activities. Furthermore, literacy on family planning needs to be escalated so as to reduce on the dependence ratio. This was also noted by UBOS (2019/20), and added that family planning usage was lowest in Karamoja in Uganda (Namuhani, 2024). Additionally, concentrating on helping more the women headed household would go an extra mile, since female headed households are said to be 65 percent (UBOS, 2019/2020). This purpose would give the Karamojong a better identity, grounding as well as a future to look up to. This also agrees with Ninsiima (2022) who reports that women are the most affected. These women headed households could be helped in income generation activities; access to resources; household management; empowerment to produce food; subsidized skills and capacity building. These would help them thrive economically, hence leveraging their potential.

6. Conclusions

- Reducing Starvation in this Karamoja region is wholly dependent on the people's individual and household rural life; in addition to the environmental factors. Therefore, the journey to abundance would also necessitate improving literacy, in particular, on personal attitude to curb theft and civil wars; usage of family planning methods to manage the high dependence ratio; sanitation to improve health care; cultural barriers on women land ownership; among others. Furthermore, the study suggests that aid, interventions or policies need to be targeted towards to resource management, access to food from other regions, as no region is easily self-reliant.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML