-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Statistics and Applications

p-ISSN: 2168-5193 e-ISSN: 2168-5215

2021; 11(3): 51-60

doi:10.5923/j.statistics.20211103.01

Received: Jun. 4, 2021; Accepted: Jul. 7, 2021; Published: Aug. 25, 2021

Survival Analysis and Predictors of Time to First Birth After Marriage in Jordan

Noora Said Salim Al Shanfari, M. Mazharul Islam

Department of Statistics, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Sultanate of Oman

Correspondence to: M. Mazharul Islam, Department of Statistics, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Sultanate of Oman.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The Waiting time-to-first birth is an important indicator of the reproductive behavior of married women. However, data on waiting time to first birth involve censoring and follow a skewed distribution, and thus need survival analysis techniques to analyze such data. The aim of this study was to model the time to first birth after marriage using survival analysis techniques and identifies the significant prognostic factors of time to first birth after marriage. The data for the study was extracted from the 2018 Jordan Population and Family Health Survey. The study considered 4,828 married women who were married within 10 years of the survey date. Descriptive statistics and non-parametric (Kaplan-Meier estimator, log-rank test) and semiparametric (Cox’s model) survival analysis techniques were used for data analysis. The overall median time to first was estimated to be 15 months, indicating that about half of the married women become pregnant within the first six months of marriage. The risk of having first birth was found to be 52%, 61%, and 74% at 15, 18, and 24 months of marriage, respectively. Cox’s proportional hazard model identified age at marriage, education, wealth index, contraceptive use status, and employment status as significant predictors of waiting time to the first birth. The moderate fertility level (about 3 births per woman) in Jordan can further be reduced by adopting a policy for delayed first birth after marriage. Policies for ensuring girls' universal education to at least a secondary level would help reduce fertility by increasing age at marriage and changing reproductive behavior.

Keywords: Time to first birth, First birth interval, Predictor, Marriage, Survival analysis, Jordan

Cite this paper: Noora Said Salim Al Shanfari, M. Mazharul Islam, Survival Analysis and Predictors of Time to First Birth After Marriage in Jordan, International Journal of Statistics and Applications, Vol. 11 No. 3, 2021, pp. 51-60. doi: 10.5923/j.statistics.20211103.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Having first birth is a significant event in the life of a woman. It not only determines her level of fertility, but also her health, career development, and social well-being [1,2]. While early childbearing increase the risk of maternal and child morbidity and mortality, delayed childbearing, on the other hand, reduces fertility and population growth and improves the standard of living of mothers through education and career development [2-5]. The length of first birth interval or the waiting time to first birth interval often used as an indicator to understand the reproductive pattern and behavior of a population [6,7]. Different studies have identified different risk factors contributing to the length of the first birth interval. Mother’s education and age at marriage are the most widely cited determinants of first birth interval. Age at the marriage of mothers is considered to be an important variable in the fertility process which is negatively associated with the length of the first birth interval [8,9]. Education has always been an important socio-economic determinant of reproductive life [10]. The other common determinants of marriage to first birth intervals are wealth status, place of residence, and employment status [1,11,12]. There is an inverse relationship between fertility and birth interval. The duration of marriage to first birth interval provides the most consistent and reliable measure of conception rate or fecundability, defined as the probability of conceiving in a month among fecundable women (excluding pregnant, sterile and amenorhheic women) [13]. In fact, the fecundability is inversely related to the duration of the conception wait [13,14]. At this crucial juncture, it is important to analyze the marriage to first birth interval data. However, one of the important features of this type of event history data collected through retrospective surveys or follow-up studies is that they involve censored or incomplete observations. Individuals that did not experience the event of interest during the study period are considered censored data. For example, consider the event of marriage to first birth interval for a random sample of married women considered in a retrospective survey. In this case, there are many women who still do not have any first birth either they just married or for various other reasons, and thus their duration of marriage to first birth is censored due to the survey date. For those who have the event, i.e. first birth (i.e., complete data), the duration of marriage to first birth is usually positively skewed. Estimating the average duration of marriage to first birth by considering only the complete data will underestimate the true duration. Tuma and Hannan [15] have proved that excluding censored data from the analysis can cause biased results. Thus, the presence of censoring complicates the research design and the statistical analysis that cannot be handled properly by standard statistical methods, such as ordinary regression models and/or logistic models. However, survival methods can be used to analyze time-to-event data that involves censoring. Over the period, various survival analysis techniques have been developed for analyzing survival data with censored observations. The aim of this study is to analyze the duration of marriage to the first birth interval and its prognostic factors in Jordan, using survival analysis techniques.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Design and Study Population

- This study utilized secondary data from the 2018 Jordan Population and Family Health Survey (JPFHS) conducted as part of the global Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) program. ICF Macro International provided technical assistance through the DHS Program, which is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and offers financial support and technical assistance for population and health surveys in countries worldwide. The details of the survey and the data may be seen in the final report of the 2018 JPFHS [16]. The survey included a nationally representative sample of 14,689 ever-married women of reproductive age. The sample was selected following a stratified cluster sampling design to provide national and subnational level estimates of major demographic and health indicators. The survey collected detailed information about marriage, birth history, and other socio-economic, demographic, and maternal and child health indicators. Our response variable is the waiting time to first birth (survival time) after marriage which includes both censored and uncensored observations. To minimize the memory recall bias associated with reporting first birth, we have considered only women who were married within 10 years of the survey date. For any individual woman, if there was an event or first birth before the survey date, the observation was considered uncensored, and the survival time for uncensored observation was calculated by subtracting the date of the marriage from the date of first birth. On the other hand, if a woman had no birth before the survey date, the observation was considered as censored, and the survival time for the censored case was calculated by subtracting the date of marriage from the date of the survey. Thus our survival time was attached with a censoring index, which was coded as 1 if the event occurred and 0 otherwise. We defined the starting point of the study as the date of the survey and looked backward for ten years. The survival time T was defined as the time from the date of marriage to the date of the first birth, and the censoring time C was defined as the time from the date of marriage to the date of the survey. In this study, we have considered only the right censoring cases, excluding the reported pregnant women and the women with a first birth interval of fewer than nine months. Under the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 4,828 women were left for our survival analysis. The explanatory variables considered in this study were: age at marriage, contraceptive use, education, ethnicity, place of residence, region, work status, and wealth index.

2.2. Survival Analysis

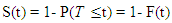

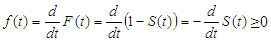

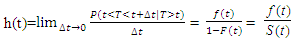

- Survival analysis is a collection of statistical procedures for data analysis for which the outcome variable of interest is time until an event occurs. It is most important when survival time involved censored observations and thus cannot be analyzed using standard statistical methods which consider only uncensored data [17]. Survival data, or time-to-event data, measure the time elapsed from a given origin to the occurrence of an event of interest. In summarizing survival data there are three functions of central interest namely the survivor function, the hazard function, and the probability function. They are briefly discussed as follows.Let T be a continuous random variable associated with the survival times of an event, t be the specified value of the random variable T, and f(t) be the underlying probability density function of the survival time T. Three quantitative terms are important in survival analysis. These are the survival function S(t), hazard function h(t), and the probability density function f(t). In the context of the present study, the survival function S(t) gives the probability that a woman “survives” longer than some specified time t without a birth, while the hazard function h(t) gives the instantaneous potential per unit time to have the first childbirth after time t, given that the individual had not had the first childbirth up to time t. The interrelationship among these functions can be shown mathematically as follows.The distribution function F(t) represents the probability that the length of waiting time to first birth for a women is less than (or equal to) a specified time t, and is given by

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

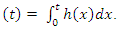

Lee and Wang [18] showed that

Lee and Wang [18] showed that  Then S(t) = exp(-H(t)) and f(t) = h(t)S(t).There are three types of models for analyzing the survival time. These are: the nonparametric models, the semi-parametric model, and the parametric models. However, in this study we have used non-parametric and semi-parametric methods. The Kaplan-Meier (K-M), Nelson-Aalen (N-A) and Life Tables (LT) are the three non-parametric methods for estimating the survival and hazard functions. Among these three methods, K-M method, developed by Kaplan and Meier [19], is the most commonly used non-parametric method in survival analysis. For a descriptive summary of the time to first birth after marriage, we used K-M estimator. In K-M method, we assume that we have a sample of n independent observations denoted by (ti, ci), i=1, 2, ….,n of the underlying survival time variable T and the censoring indicator variable C. Among the n observation, let there are m≤n recorded time of first birth. Let

Then S(t) = exp(-H(t)) and f(t) = h(t)S(t).There are three types of models for analyzing the survival time. These are: the nonparametric models, the semi-parametric model, and the parametric models. However, in this study we have used non-parametric and semi-parametric methods. The Kaplan-Meier (K-M), Nelson-Aalen (N-A) and Life Tables (LT) are the three non-parametric methods for estimating the survival and hazard functions. Among these three methods, K-M method, developed by Kaplan and Meier [19], is the most commonly used non-parametric method in survival analysis. For a descriptive summary of the time to first birth after marriage, we used K-M estimator. In K-M method, we assume that we have a sample of n independent observations denoted by (ti, ci), i=1, 2, ….,n of the underlying survival time variable T and the censoring indicator variable C. Among the n observation, let there are m≤n recorded time of first birth. Let  are the rank-ordered survival time of first birth. Let

are the rank-ordered survival time of first birth. Let  be the number of women exposed to have a first birth at

be the number of women exposed to have a first birth at  and

and  be the observed number of women with first birth at

be the observed number of women with first birth at  , then the K-M estimator of the survivorship function at time t is obtained from the equation

, then the K-M estimator of the survivorship function at time t is obtained from the equation | (5) |

After obtaining summary statistics of survival time, a comparison of the survivorship experience of subgroups defined by the categories of a covariate were made. To test the statistical significant difference in survival time across the subgroups, log-rank (LR) test was used. The incidence rate (IR) of marriage to first birth, which is the probability that a woman would have a first birth after marriage at time tk+1 given that she has not had a child by time tk, was also determined. It is the probability of first birth occurring after a particular interval (time after marriage) given that the woman has had no birth before then. To obtain the net-impact of the explanatory variables on time to first birth after marriage, we then applied semi-parametric model known as the Cox Proportional Hazard model [20]. In proportional hazard model, the effect of a unit increase in covariate is multiplicative with respect to hazard rate. The general form of the proportional hazard model is given as

After obtaining summary statistics of survival time, a comparison of the survivorship experience of subgroups defined by the categories of a covariate were made. To test the statistical significant difference in survival time across the subgroups, log-rank (LR) test was used. The incidence rate (IR) of marriage to first birth, which is the probability that a woman would have a first birth after marriage at time tk+1 given that she has not had a child by time tk, was also determined. It is the probability of first birth occurring after a particular interval (time after marriage) given that the woman has had no birth before then. To obtain the net-impact of the explanatory variables on time to first birth after marriage, we then applied semi-parametric model known as the Cox Proportional Hazard model [20]. In proportional hazard model, the effect of a unit increase in covariate is multiplicative with respect to hazard rate. The general form of the proportional hazard model is given as | (6) |

| (7) |

3. Result

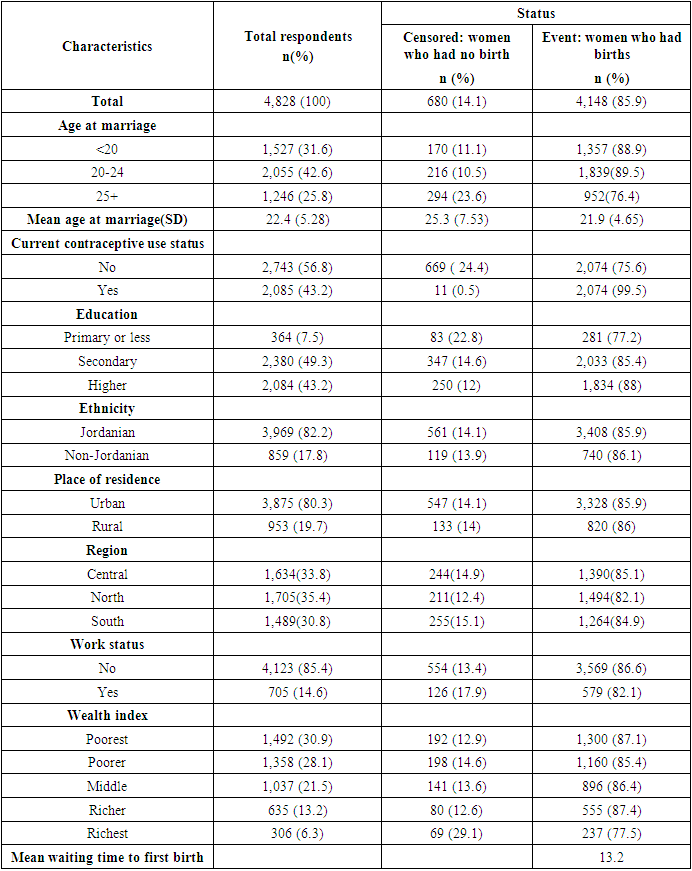

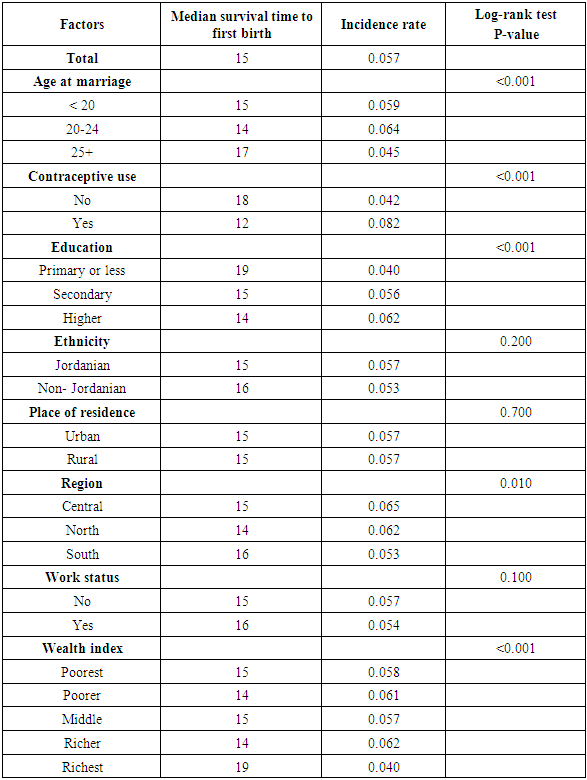

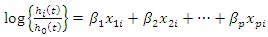

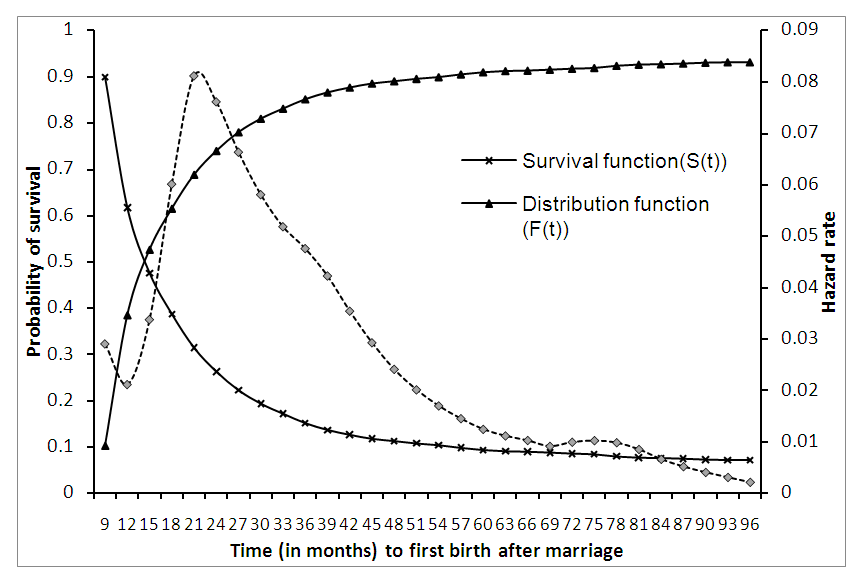

- Out of the 4,248 women considered in this study, 4148(85.9%) had given birth before the survey date and the rest 680(14.1%) had not given birth before the survey date, these later groups of women were considered as censored cases in survival analysis. For those who had a birth, the median waiting time to first birth after marriage was 13.2 months, and the skewness of waiting time to first birth after marriage was found to be 3.48. This indicates that the data on waiting time to first birth is highly skewed to the right. Nearly one-third (32%) of the women were married before age 20, 43% were married between age 20-24 years, while 26% were married at ages 25 and above (Table 1). The mean age at marriage was found to be 22.4 years. An overwhelming majority (93%) of the women had a secondary or above level of education. More than half (57%) of the women were contraceptive users at the time of the survey. About 82% of the women were native Jordanian, and 80% of the women were living in urban areas. About 15% of the respondents were engaged in employment. More than half (59%) of the women belonged to the poorest or poorer categories of wealth quintiles. The data in Table 1 indicate that the censored cases (i.e. women who did not have birth within 10 years before the survey date) and non-censored cases (i.e. women who had a birth before the survey date) differ according to their socio-demographic characteristics. Censoring cases occurred at a substantially higher rate among the women with higher age at marriage, having primary or less education, non-users of contraceptive, employed, and with richest wealth index.

|

| Figure 1. Survival function, distribution function and hazard function of time to first birth after marriage |

| Figure 2. Survival function of time to first birth after marriage by characteristics of women |

|

|

4. Discussion

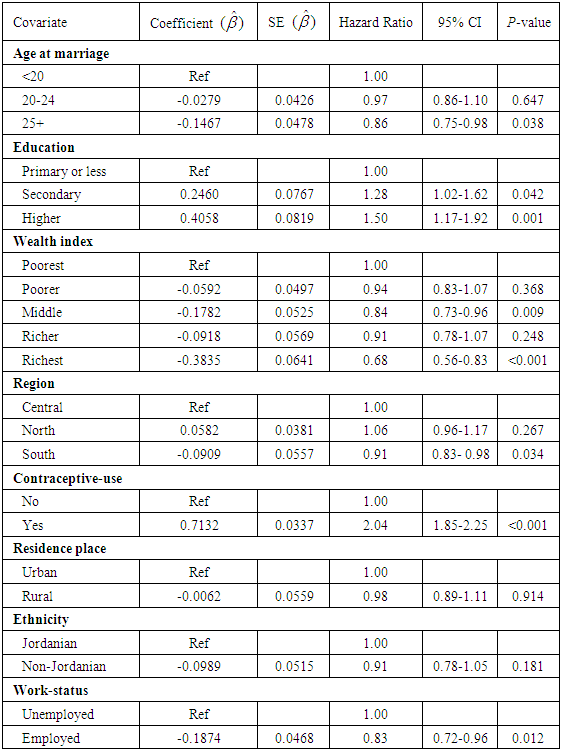

- The aim of this study was to analyze the time-to-first birth after marriage, using the most recent Jordan Population and Family Health Survey (JPFHS) data of 2018. Since the time-to-first birth after marriage involved censoring events, which precludes the use of classical statistical models for analyzing such data, we applied survival analysis techniques. Both non-parametric (K-M method) and semi-parametric (Cox’s model) methods have been used for analyzing time-to-first birth data and identify the prognostic factors of time to first birth occurrence. The median time to first birth after marriage was observed to be 15 months in Jordan. The risk of having first birth within 10 years of marriage before the survey date was found to be 52%, 61%, and 74% at 15, 18, and 24 months of marriage, respectively. The results indicate that about half of the married women become pregnant within the first six months of marriage. The median time to first birth after marriage in Jordan is relatively shorter than observed in most countries in South Asia and Africa. For example, in a recent study in Ethiopia, the median time to first birth was observed to be 30 months [21], while the median time of first birth interval was observed to be 20 months for Nigerian women [1], 25.2 months for Iranian women [9], and 25 months for Bangladeshi women [22]. The quick transition from marriage to first birth or shorter first birth interval in Jordan might be related to higher age at marriage and a lower rate of contraceptive use among the married women in the county compared to the women in Ethiopia or India. For example, among the married women considered in this study, 43.0% were using any family planning methods, while in Ethiopia, 74% of women were using any family planning methods. On the other hand, the median age at marriage in Jordan was 22 years, compared to 16 years in Ethiopia. Early marriage (i.e., below age 20) leads to a longer duration of marriage to the first birth interval due to the sub-fecundity of the adolescent girls.Both non-parametric (log-rank test) and semi-parametric method (Cox model) identified age at first marriage, wealth index, education level, region, contraceptive use, and work status as significant prognostic factors of timing to first birth after marriage. Age at first marriage was found to be negatively associated with the hazard of first birth in Jordan, indicating delayed first birth among the women with higher age at marriage. This is conceivable, as the women with higher age at marriage might be more concerned about fertility control through spacing births. Our result is consistent with the findings of other studies [1,9,23]. A significant negative association was found between women's education and time-to-first birth. Women with secondary and above level education have a significantly shorter duration of first birth interval compared to women with primary or less education. This finding is consistent with the findings of the study conducted in Bangladesh and India [24], Iran [9], and Ghana [25]. Women's educational attainment is a strong predictor of the reproductive behavior of women. Women with the secondary and above level of education spend a substantial amount of time in achieving education and thus likely to have entry into reproduction at a higher age, and thereby likely to have first birth quickly after marriage to compensate their late entry and achieve the desired level of fertility. Our findings, however, contradict the findings of the study of Fagbamigbe and Idemudia [1] in Nigeria; reporting women with no education or primary education had higher hazards of having first childbirth than those with higher education.Another important finding of this study was that the employment status of the women had a significant association with time-to-first birth. The time-to-first birth interval following marriage for employed women was longer than for unemployed women. This is consistent with studies done in Bangladesh [26], Indonesia [12], and Ethiopia [21]. The results indicate that the contraceptive users had a higher hazard of first birth and thus shorter first birth interval than their non-users counterparts. Our findings contradict the findings of many studies documenting higher first birth interval for contraceptive users than the non-users of contraceptive, as contraceptive use help delaying birth [27-30]. It is worth mentioning here that we have considered current contraceptive use status, rather than at the time before first birth. As a result, it may happen that most of the current users in our study become contraceptive users after having their first birth in a quick succession after marriage.The key strength of this study is that it is based on a nationally representative sample and population-based data, and thus the findings are generalizable to the national as well as sub-national levels. The study findings may have important policy implications for fertility planning in Jordan. The study has the potential to contribute to the literature. Nonetheless, the study is not free from limitations. The data used in the study is cross-sectional in nature which was obtained through retrospective interviews of a selected group of women who were married within 10 years of the survey date, and thus may have introduced recall biases and restricts the interpretation of causality. Further, using secondary data-limited us in the choosing of variables that were available.

5. Conclusions

- The median time of transition from marriage to first birth was observed to be 15 months, which is shorter than most other developed and developing countries. The level of education showed a significant positive association with the hazard of first births and thus leading to a faster transition to the first birth. The wealth index showed a slower transition to first birth after marriage among women from middle and richest wealth index groups, leading to higher birth intervals. Women with employment were found to be less likely to have a faster transition to first birth, leading to a longer first birth interval. The early timing of first birth in Jordan might have contributed to the moderate total fertility rate of 2.7 births per woman. The fertility rate could further be reduced by adopting a policy to increase the gap between marriages to the first birth. Considering the prevailing complex socio-cultural norms in Jordan, direct intervention for delayed first birth may be difficult. However, policies for ensuring girls' universal education to at least a secondary level would help reduce fertility by increasing age at marriage and changing reproductive behavior.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We thank MEASURE DHS for granting access to Jordan Population and Family Health Survey datasets. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of any institution or organization.

Conflict of Interests

- The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethics Approval

- JPFHS data are public access data and were made available to us by MEASURE DHS upon request. Ethical clearance to conduct the JPFHS was approved by the Government of Jordan.

Financial Support

- No financial support received for conducting this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML