-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Statistics and Applications

p-ISSN: 2168-5193 e-ISSN: 2168-5215

2017; 7(5): 268-273

doi:10.5923/j.statistics.20170705.04

Impact of Demographic Characteristics on USASF Members' Perceptions on Recent Proposed Rule Changes in All Star Cheerleading

Aricka Gates, Lucy Kerns

Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Youngstown State University, Youngstown, USA

Correspondence to: Lucy Kerns, Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Youngstown State University, Youngstown, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The primary goals of this study were to examine the U.S. All Star Federation (USASF) members' perceptions on the recent proposed rule changes and policy updates in All Star cheerleading, and to explore the relationship between members' demographic characteristics (role, experience, gender, etc.) and their views on the proposed changes. An internet-based market research survey was conducted to gather information and feedback from the members, and statistical techniques were then used to interpret the collected information, to formulate facts and uncover patterns in the research. Our findings revealed that USASF members' perceptions on the rule changes are significantly affected by some demographic characteristics. The present findings provide USASF administrators with an in-depth view of their members that could be useful to the organization's Rules Committee and may help support the development and maintenance of new rules guiding the competitions.

Keywords: Logistic regression, Demographics, Quantitative study, Athletes

Cite this paper: Aricka Gates, Lucy Kerns, Impact of Demographic Characteristics on USASF Members' Perceptions on Recent Proposed Rule Changes in All Star Cheerleading, International Journal of Statistics and Applications, Vol. 7 No. 5, 2017, pp. 268-273. doi: 10.5923/j.statistics.20170705.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Cheerleading is an American tradition begun in 1898 when a medical student named Johnny Campbell assembled a group of students and led the first cheers at a Minnesota University football game (Shields & Smith, 2006; Boden, Tacchetti, & Mueller, 2003). Cheerleading has continued to grow over the years and has served primarily the purpose of raising school unity through leading the crowd in cheers at athletic functions (The American Association of Cheerleading Coaches and Administrator). As the popularity of cheerleading grew, so did the skill level of the cheerleaders participating. Since 1980, cheerleading has evolved from leading the crowd in cheers at sporting events to a competitive year-round activity demanding high levels of skill and athleticism. Some states consider cheerleading a school activity, and others consider it a sport (Shields & Smith, 2006).The all star cheerleading is thought to be the fastest growing segment of the cheerleading industry. While scholastic cheerleaders are usually associated with a school and their main objective is to cheer for other sports teams, such as basketball and football teams, all star cheerleaders are normally associated with for-profit gyms that teach tumbling, high-level stunting, pyramid-building, gymnastics, and cheerleading. All star cheerleaders join the gym for the sole purpose of learning the skills and competing, and they are dedicated to practicing and performing. The governing body of all star cheerleading in the United States is the U.S. All Star Federation (USASF, http://usasf.net), a nonprofit organization founded in 2003. The USASF sets the industry’s standards by making and enforcing rules for competitive cheerleading. There are about 150,000 athletes and 15,000 coaches that are currently registered members of the USASF.Cheerleading, especially all star cheerleading, features complex acrobatic stunts, advanced tumbling, high pyramids, in addition to dance. As routines become more complicated and advanced, cheerleader are at high risk of catastrophic injury. Many studies have reported cheerleading injuries. Hutchinson (1997) concluded based on two case reports that cheerleading injuries are attributed to lack of experience, inadequate conditioning, insufficient supervision, difficult stunts, and inappropriate surfaces and equipment. Boden, Tacchetti, & Mueller (2003) reviewed many incidents of cheerleading injuries reported to the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research from 1982-2002 and made few recommendations for reducing catastrophic injuries in cheerleaders. Schulz at el. (2004) investigated injury incidence in a sample of North Carolina female cheerleaders who competed interscholastically from 1996 to 1999 and found that cheerleaders supervised by coaches with more education, qualifications, and training had a significant reduction in injury risk compared to cheerleaders supervised by coaches with low coach education, qualifications, and training. Other studies include Hage (1981, 1983), Murphy (1985), Fort & Fort (1999), Jacobson et al. (2004), and Shields & Smith (2006, 2009).The USASF’s mission statement is, “To support and enrich the lives of our all star athletes and members. We provide consistent rules, strive for a safe environment for our athletes, drive competitive excellence, and promote a positive image for the sport.” To achieve their mission, the USASF institutes rules, guidelines, and policies that their members must abide by, and the rules and guidelines are constantly updated to keep athletes safe. New studies that provide information on how to achieve proper development and protect the safety of young athletes are being performed every year. The USASF has a Rules Committee that is tasked with developing, maintaining, and enforcing rules in the cheerleading industry. Every two years the Rules Committee polls the USASF members using an online survey to determine their opinions on proposed rule changes and policy updates.The survey examined in this study was sent out to the professional members of the USASF to gather their opinions on the most recent proposed rule changes. In the past, the results from these polls were simply looked at votes. It is important to count the votes from the members to gather their views; however, it is also critical to examine the votes to see if the perceptions of the members are related to the demographic variables given by each member. The demographic information in the survey includes the region of the program to which a member belongs (southwest, southeast, northeast, midwest, and west), the role of the member (owner, coach, or program director), gender of the member, the size of the gym that the member is from (small or large), the level of all star teams that the member is coaching (level 1, 2, 3,4, 5, or 6), current program status (single location, multiple locations sharing athletes, or multiple locations not sharing athletes), type of teams (all star, co-ed, special needs, worlds eligible, or international open), and others. We expect that members will have different views about the proposed rule changes due to their different demographic characteristics. For example, Owners tend to view all star cheerleading through a business lens, and they have to be concerned with the amount of money the business is making; coaches spend a lot of time with the athletes and because of their experience, they may have different opinions than those of the owners regarding certain topics. To help support the development and maintenance of new rules governing competitive all star cheerleading, it is important to understand their views of the rules guiding the competitions. To our knowledge, there is no published study examining how USASF members' demographic characteristics influence their views on the rule changes in cheerleading. The current study seeks to bridge the knowledge gap by exploring the perceptions of coaches and gym owners regarding the rule changes and policy updates proposed by the Rules Committee of USASF.The survey contained several different questions about rule change policies; for example, revising program definition, designating an entry age for All Star Cheer, prohibiting MINI Level 2 teams from performing tosses, and others. The main purposes of the current study are: 1) to explore whether USASF members' views on rule changes differentiate on the basis of their demographic characteristics (role, gender, location, region, etc.); and (2) to investigate how these demographic characteristics effect the USASF members' opinions on proposed rule changes.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

- Participants were 1196 registered USASF members who passed their background checks and were up to date on their membership fees. Data from 176 participants were excluded in further analysis due to failure to answer some questions in the questionnaire. The final data set contains 1020 participants (756 females and 264 males). Of the 1020 participants, 494 identified themselves as coaches, 163 as directors, 316 as owners, and 47 as others. With regard to the age of the participants, 378 respondents aged between 18 and 29, 553 aged between 30 and 49, and 89 aged 50 or older.

2.2. Materials

- The survey included questions on demographic information as well as rule changes. Eight demographic variables were examined in this study: region, role, experience, size, division, location, Level 5/6, gender, and age.The first demographic variable examined was region. The USASF is broken down into five regions: West, Northeast, Southeast, Southwest, and Midwest. The role variable examined the primary job of the member completing the survey and was broken down into four options: owner, coach, program director, or other. The demographic variable of experience was a discrete variable that looked at how many years the member has been involved in All Star Cheerleading. The variables of size and division were closely related. The size variable looked at the number of cheer athletes the program thought they would have for the 2016-2017 season. There were nine options the member could pick from: less than 50, 51-75,76-100, 101-125, 126-150, 151-175, 175-200, 200-299, and 300 or more. The USASF contains two divisions. Division II contains programs with less than 126 athletes, while Division I is made up of programs with more than 126 athletes. Location was a demographic variable that was concerned with the number of different locations a program had. There were three options the member could choose: single location, multiple locations sharing athletes, multiple locations not sharing athletes. Levels represent the difficult of the routines performed and the skills of the athletes. Levels 5 and 6 are the highest levels. Teams that compete in these levels are performing the most advanced routines. The variable Level 5/6 was a binary variable, with “1” indicating that the program has a Level 5 and /or a Level 6 team and “0” indicating that the program did not have a Level 5 or Level 6 team. The variable gender was a binary variable with two categories, male and female. The last demographic variable used in this study was the age of the member completing the survey, which was divided into three categories, 18-29, 30-49, and 50 or older.In addition to the demographic variables, the survey asked several questions regarding the recent rule change policies to learn the participant's perceptions on these issues. It asked participant's opinions about the revision in program definition, the designated age for entering all star as a competitive cheer athlete, the changes in the cross over guideline, and a number of specific rule changes in guidelines (for example, changing the rule from permitting all level 2 teams to perform tosses to prohibiting mini level 2 teams from performing tosses, changing the current level 6 stunt rules from “Helicopters up to 180 degree rotation requires 3 catches” to “Helicopter up to 180 degree rotation to be caught by at least 2 catches”, etc.). For the purpose of this study, two questions will be closely examined, program definition and the designated age for entering all star as a competitive cheer athlete.The question on program definition, in particular, asked participant’s view on the definition of “Branded Programs” (programs who have more than one location). Respondents have three options to choose from, “I am in favor of keeping as is”, “I am in favor of change”, and “Abstain”. In this article, the three categories for program definition will be referred to as keep, change, and abstain. Regarding the question of entry age for All Star cheer, participants were asked whether they believed there should be a designated age to enter All Star as a competitive cheer athlete, and were provided with three options, “Yes - I am in favor of implementing an entry age to enter All Star”, “No - I am not in favor of implementing an entry age to enter All Star”, and “Abstain”.

2.3. Procedure

- The data used in this study were collected using the web-based survey tool Survey Monkey, administered by the USASF. All USASF professional members received emails inviting them to participate in the online survey, and were provided with explanations for the background and purpose of conducting the survey. Participants had one week to fill out the survey, and their anonymity was preserved.

3. Data Analysis

- Data were analyzed using RStudio version 0.99.903. All of the variables except for the variable age are categorical variables in the study. The descriptive statistics of the variables were calculated first to describe the basic features of the data in the study. Contingency tables and Person's chi-squared test were used to assess the relationship between each categorical demographic variable and response variable (program definition and entry age). Logistic regression was performed to further explore possible determinants of the response variables.

4. Results

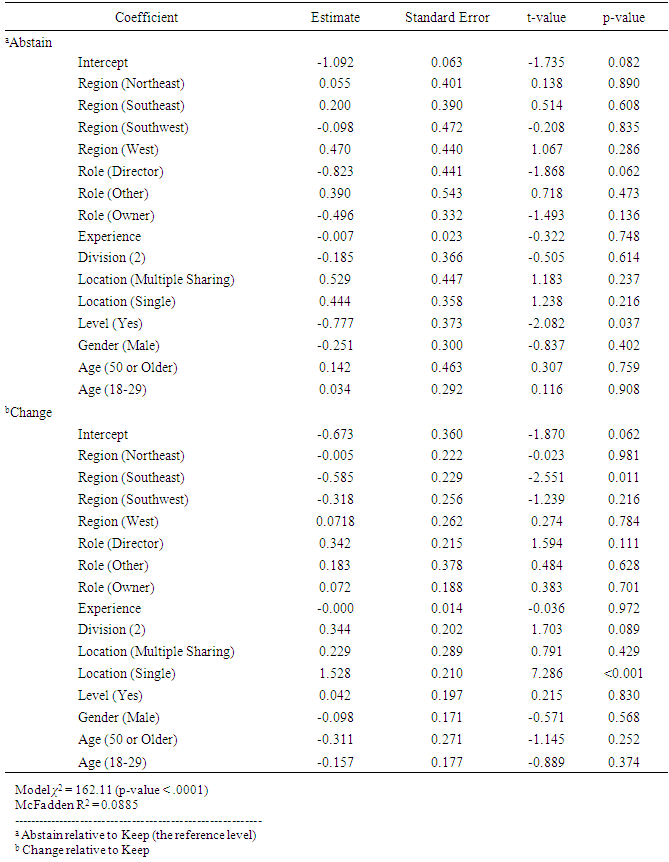

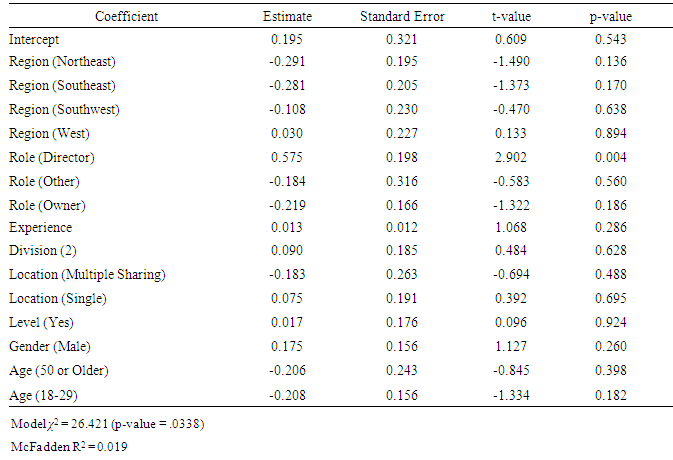

- The 1020 participants in the study were categorized by the aforementioned demographics as follows:• Region: 18.1% (Midwest), 28.2% (Northeast), 24.1% (Southeast), 14.6% (South- west), and 15.0% (West).• Role: 48.4% (Coach), 16.0% (Director), 31.0% (Owner), and 4.6% (Other).• Experience: mean 10.4 (years) and standard deviation 6.44 (years).• Division: 31.9% (Division 1) and 68.1% (Division 2).• Location: 19.1% (Multiple Not Sharing), 8.9% (Multiple Sharing), and 72.0% (Single).• Level 5/6: 53.5% (No) and 46.5% (Yes).• Gender: 74.1% (Female) and 25.9% (Male).• Age: 37.1% (18-29), 54.2% (30-49), and 8.7% (50 or older).Regarding the response variable program definition, of the 1020 participants, 363 (35.4%) chose the option “keep”, 574 (56.3%) chose the option “change”, and 85 (8.3%) chose “abstain”. For entry age, the number (proportion) of participants who voted for “Yes”, “No”, and “Abstain” was 565 (55.4%), 449 (44.0%), and 6 (0.59%), respectively.It was observed from the chi-squared test that there was a significant association between program definition and all demographic variables except for the variable age, with the p-values of .0002 (region), .015 (role), <0.0001 (division), <0.0001 (location), <0.0001 (Level 5/6), and .02098 (gender). Contingency tables revealed that respondents from the region southeast are least likely to vote for “change" compared with other respondents, owners are more likely to favor “change”, and more participants from Division 2 programs are in favor of “change” compared with Division 1. For the variables location, Level 5/6, and gender, it seemed that the option “change” was more favored by participants from single location, participants associated with gyms that had a Level 5 and/or a Level 6 team, and female respondents. The variable entry age did not show a significant association with any of the demographic variables except for the variable role (p-value = .016). Upon closer examination of the contingency table between entry age and role, we noticed that directors were most likely to favor the option of implementing an entry age, while there was no distinguishable difference between other respondents.Table 1 shows the results from a multinomial logistic regression with program definition as the response variable. There are two sets of logistic regression coefficients in the table. The first set of coefficients are found in “Abstain” row, which represents the comparison of the category “Abstain” to the reference category “Keep”. We can see that the variable Level 5/6 is statistically significant (p-value = 0.037), and the estimated coefficient -0.0777 indicates that after controlling for all other demographical variables, respondents who are associated with gyms that did not have a Level 5 or a Level 6 team are about twice more likely to vote for “Abstain” than for “keep”, compared with those who are from gyms that had a Level 5 and/or a Level 6 team.

|

|

5. Conclusions

- The main goals of this market research study were to gather information and feedback from the members of USASF concerning their views on the recent proposed rule changes and policy updates, and to get an in-depth view of the members by investigating which participant characteristic(s) (region, role, experience, size, division, location, Level 5/6, gender, and age) influence their perceptions, if any. Logistic regressions were performed to explore the effects of demographics on the likelihood of response options. Logistic regression models were statistically significant, and the results suggest that participants have different views on the rule change policies due to their different demographic characteristics; in particular, three demographic variables, region, location, and Level 5/6, were identified as important predictor variables for the two specific responses that we examined in this study, program definition and entry age. The findings showed that participants who are associated with gyms having single location are much more likely to favor the changes in the program definition, and directors tend to favor the option of implementing an entry age to enter an All Star cheerleading program. The results of this study provide insights into factors associated with different response options that could be useful to the Rules Committee. As participants' perceptions on other rule change policies and the relationship between their demographics and views are also of interest to the Committee, further research could be conducted to explore USASF members' perceptions of other proposed rule changes and policy updates.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML