-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Statistics and Applications

p-ISSN: 2168-5193 e-ISSN: 2168-5215

2015; 5(4): 133-140

doi:10.5923/j.statistics.20150504.01

Analysis of Chronic Disease Conditions in Ghana Using Logistic Regression

Azumah Karim1, Bashiru I. I. Saeed2, Kwaku F. Darkwah3, A. A. I. Musah4

1Graduate Student of Mathematics and Statistics Department, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

2Mathematics and Statistics Department, Kumasi Polytechnic, Kumasi, Ghana

3Mathematics and Statistics Department, KNUST, Kumasi, Ghana

4Mathematics and Statistics Department, Tamale Polytechnic, Tamale, Ghana

Correspondence to: Azumah Karim, Graduate Student of Mathematics and Statistics Department, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The impact of chronic diseases on the development of a nation cannot be overemphasized. The influences of socio-demographic/socio-economic factors on chronic disease conditions in Ghana are not well comprehended. The aim of this paper is to examine the effect of socio-demographic/socio-economic factors of Ghanaians on their chronic disease conditions. A longitudinal study with nationally representative samples was undertaken. The data employed in this study were drawn from the World Health Organization Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE), Wave 1, 2008-2009. The study suggested some level of chronic diseases in the Ghanaian populations. Asthma recorded the highest prevalence conditions with 3.4%, while Lung Disease recorded the least, 0.6%. However, Depression, Oral health, and Injuries fairly recoded 1.4%, 2.5% and 1.8% respectively. In addition, the strength of the age category groups tends heavily towards adults, and particularly older adults respectively. Most of the respondents belong to the Christian faith. There is fairly even distribution among males and females respectively. More than half of respondents were engaged in self-employment. Majority of the respondent belongs to the Akan ethnic group. Also, widowed respondents contracted depression and oral health disease conditions. This paper revealed that, in Ghana, the occurrences of chronic disease conditions are associated with some socio-demographic/socio-economic factors: age, sex, religion, ethnicity, marital status, occupation, level of education, and income levels.

Keywords: Chronic diseases, Logistic regression, Socio-demographic/socio-economic factors, Odds ratios

Cite this paper: Azumah Karim, Bashiru I. I. Saeed, Kwaku F. Darkwah, A. A. I. Musah, Analysis of Chronic Disease Conditions in Ghana Using Logistic Regression, International Journal of Statistics and Applications, Vol. 5 No. 4, 2015, pp. 133-140. doi: 10.5923/j.statistics.20150504.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- A chronic condition is a human health condition or disease that is persistent or otherwise long-lasting in its effects. The term chronic is usually applied when the course of the disease lasts for more than three months. Common chronic diseases include arthritis, asthma, depression, oral health, injuries, cancer, diabetes and HIV/AIDS. Aside genetic factors, some of these conditions may be influenced by socio-demographic/socio-economic factors of Ghanaians.Chronic diseases have a longer history in Ghana than is usually thought. Cancer of the liver was recorded in 1817 Asante communities; sickle cell disease was described in 1866.Cases of stroke were presented and treated at Korle-Bu hospital when it opened in the 1920s.Between the 1920s and the 1960s data gathered from Korle-Bu hospital showed a steady increase of stroke and cardiovascular diseases. In Accra, cardiovascular diseases rose from being the seventh and tenth cause of death in 1953 and 1966 respectively, to becoming the number one cause of death in 1991 and 2001.Chronic diseases constitute a major cause of mortality and the World Health Organization (WHO) reports chronic non-communicable conditions to be by far the leading cause of mortality in the world, representing 35 million deaths in 2005 and over 60% of all deaths.According to Pols et al, 2009, chronic conditions will account for 80% of global disease burden by the year 2020. The contribution of socio-demographic/socio-economic factors on chronic diseases has received a lot of attention in the developed world, (Sue Ziebland and Renata Kokanovic, 2012, Brennan & Singh, 2012, Bowling 2005; Poon, Gueldner and Sprouse 2004; Mollenkopf and Walker 2007), but the same cannot be said for the developing countries including Ghana. A study of the effect of Socio-economic/ Socio-demographic status and its impact on chronic conditions is a complex one and requires a scientific research. Again, a report by Mary Anne Morgan, (2003), reported that chronic disease has become the leading killer and biggest single threat to quality of life in the United States. Diseases like cancer, heart disease and asthma disproportionately affect low income, ethnically diverse communities. As a study by Teprey, G. et al, NCD Programme 2001 Report, 2001, indicated that hypertension and obesity are major risk factors for chronic diseases. According to Gugiu et al. (2009) indicated that; Although the traditional healthcare system is designed to respond to episodic illnesses, chronic illnesses, such as diabetes mellitus, require ‘continuing medical care and patient self-management education to prevent acute complications and to reduce the risk of long-term complications’ (p. S13)The underlying determinants of chronic diseases are a reflection of the major forces driving social, economic and cultural change -globalization, urbanization, population ageing, and the general policy environment (WHO 2005). Chronic diseases account for the greatest share of death and disability worldwide. Over the next few decades this burden is projected to rise particularly fast in the developing world. The lack of research on the economic implications of chronic disease contrasts with the available knowledge on the sheer epidemiological burden of the problem. This paper assesses and evaluates the current causes, with a primary focus on developing countries. Very few such attempts have been undertaken, especially with an interest in developing countries. Thus a critical review of the available evidence is a necessary first step in exploring the case for governments and donors to invest in chronic disease prevention and in clarifying areas in which further research is required. As the evidence is complex, the report should meet the needs of technical audiences for whom detailed knowledge is central as well as be accessible and useful to those for whom synthesised understanding is sufficient source, cited by (M Suhrcke, D Stuckler, S Leeder, S Raymond, D Yach and L Rocco).The prevalence of chronic diseases and their risk factors has increased over time and contributes significantly to Ghana's disease burden. Conditions like hypertension, asthma, depression, stroke and diabetes affect young and old, urban and rural, and the wealthy and poor communities. It is the concern of the researcher that, Social factors, e.g., socioeconomic status, education level, and race/ethnicity, are also a major cause for the disparities observed in the cause of chronic disease conditions.The debilitating and often fatal complications of cardiovascular disease (CVD) are usually seen in middle-aged or elderly men and women, (World Health Organization 2007).Chronic illnesses cause about 70% of deaths in the US and in 2002 chronic conditions (heart disease, cancers, stroke, chronic respiratory diseases, diabetes, Alzheimer's disease and kidney diseases) placed sixth of the top ten causes of mortality in the general US population.The urban wealthy are not the only high risk groups for chronic diseases in Ghana. Poverty appears to be a risk factor for both communicable and non-communicable disease. There is growing evidence that some infectious diseases precipitate chronic diseases and that some chronic conditions place sufferers at risk of infectious diseases. Since the 1970s studies in poor communities in Accra have demonstrated stronger co-existence of communicable and non-communicable diseases compared to wealthier communities. These communities are also likely to suffer complications of, and die prematurely from, chronic diseases because they lack access to quality healthcare.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Collection

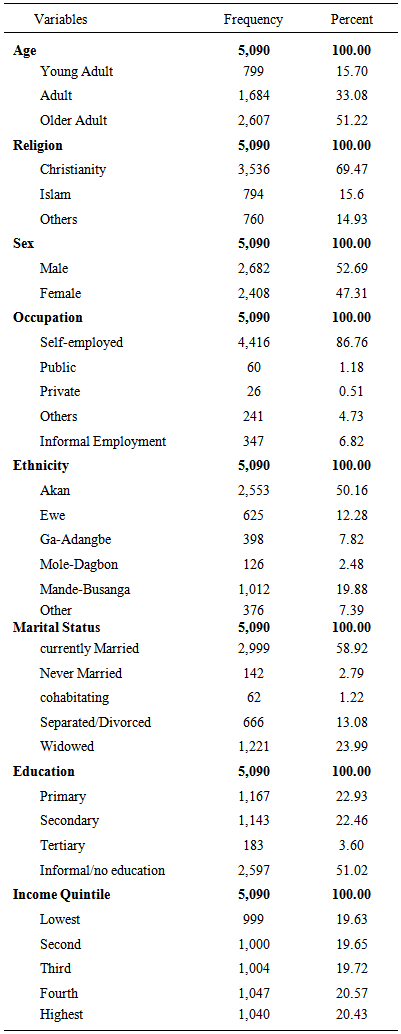

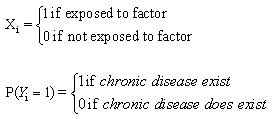

- The data employed in this study were drawn from the World Health Organization Study on global AGEing and Adult Health (SAGE), Wave 1, 2008-2009.However, each chronic disease considered in the study (i.e. the dependent variable) were: lung disease, asthma, depression, oral health, and injuries. The predictor variables included gender, age, education, occupation, income level, ethnicity, marital status, and religion.The chronic disease conditions were coded as existence or nonexistence of condition. The predictor variables coded as; Age-(young adult, adult and older adult), Religion-(christiany, Islam and others), Sex-(female and male), Occupation-(self-employed, public, private, informal and others), Ethnicity-(akan, ewe, ga-adangbe, mole-dagbon, mande-busanga and others), Marital Status-(currently married, never married, cohabiting, separated/divorced and widowed) Education-(primary, secondary, tertiary and others) and Income levels from (1-lowest to 5-highest).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

- The generalized linear regression (GLR) models are being employed in carrying out of data analysis. The (GLR) models are a natural generalization of the familiar classical linear models. The class of GLR models the binary logistic regression models for binary data was used. The Statistical Product and Service Solutions (later designation) by Academic & Science » Universities was employed in capturing the data. The Statistical Analysis, STATA (version 12.1) package was used in analyzing and fitting the binary logistic regression models.

2.3. Logistic Regression Model

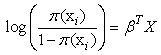

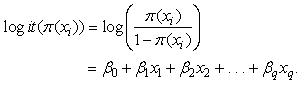

- The GLM that uses the logit link is called a logistic regression model. The logistic regression is a member of general class of linear models that are made up of three components: Random, Systematic, and Link Function (Agresti, A., 2007).Random component: Identifies dependent variable (Y) and its probability distribution. That is, the response variable which is binary variable,

or 0 (existence of chronic disease or nonexistence of the chronic disease). The probability distribution follows a binomial distribution.The Systematic Component: Identifies the set of explanatory variables

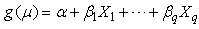

or 0 (existence of chronic disease or nonexistence of the chronic disease). The probability distribution follows a binomial distribution.The Systematic Component: Identifies the set of explanatory variables  Link Function: Identifies a function of the mean that is a linear function of the explanatory variables

Link Function: Identifies a function of the mean that is a linear function of the explanatory variables

2.4. Fitted Logistic Regression Model

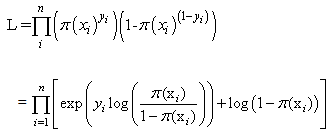

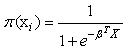

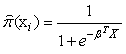

Given a logistic regression model, we observed the outcome of the independent binomial trials with probability

Given a logistic regression model, we observed the outcome of the independent binomial trials with probability  Let

Let  be the observed responses. Then the total likelihood is

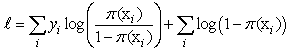

be the observed responses. Then the total likelihood is and so the log-likelihood is

and so the log-likelihood is  Since

Since  For some unknown vector of

For some unknown vector of  where

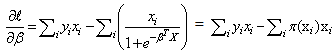

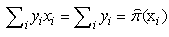

where  Using the maximum likelihood to fit the models yields a set of equations to solve from considering

Using the maximum likelihood to fit the models yields a set of equations to solve from considering

By using the assumed linear relation between the log odds and the predictorsThis means that the MLE satisfies

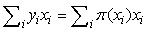

By using the assumed linear relation between the log odds and the predictorsThis means that the MLE satisfies  Since MLEs are invariant under transformation hence

Since MLEs are invariant under transformation hence  if

if  has a component of

has a component of  that is always 1, for every

that is always 1, for every  then

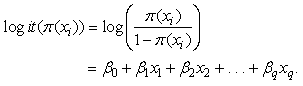

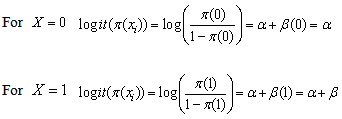

then  hence the empirical proportion of the positive responses matches the average of the fitted probabilities.The logistic model for:

hence the empirical proportion of the positive responses matches the average of the fitted probabilities.The logistic model for:  is the probability of the chronic disease for a given value of the predictors.

is the probability of the chronic disease for a given value of the predictors. Where

Where  are the predictors

are the predictors

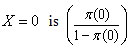

The Odds of the disease when

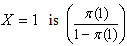

The Odds of the disease when  The Odds of the disease when

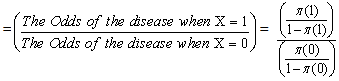

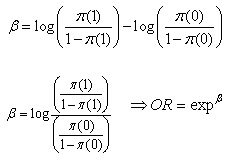

The Odds of the disease when  The Odds Ratio (OR) of the disease

The Odds Ratio (OR) of the disease  Since

Since

3. The Results

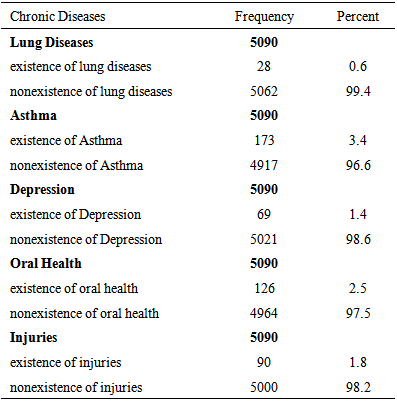

- The results of the study showed that, Asthma recorded the highest prevalence conditions with 3.4%, while Lung Disease recorded the least, 0.6 %. However, Depression, Oral health, and Injuries fairly recorded 1.4%, 2.5% and 1.8% respectively presented in Table 1.

|

|

|

4. Discussion

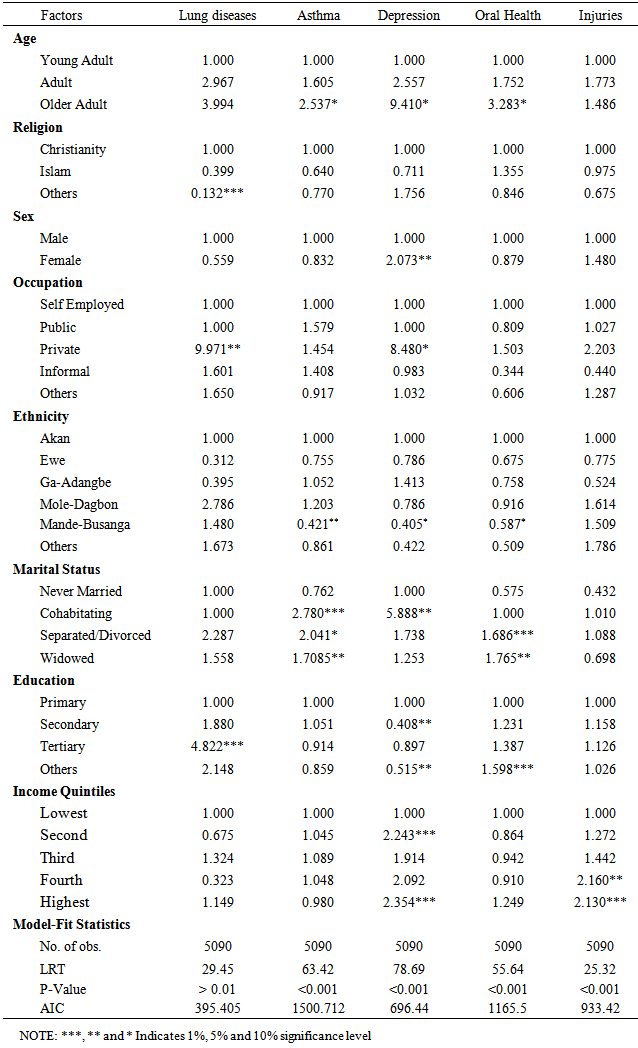

- This study established the effect of influential socio-demographic/socio-economic factors on chronic illness conditions of Ghanaians on social and medical science literature. Research conducted in various countries shows that particularly many problems are associated with health-related quality of elderly people’s lives (Bowling 2005; Poon, Gueldner and Sprouse 2004; Mollenkopf and Walker 2007). Accordingly, the avoidance of illness as well as the preservation of physical and cognitive functions is some of the most important factors that significantly improve the quality of life in the elderly age. Different studies also conclude that health is one of the most priced values for elderly people (Bowling and Gabriel 2007). Poor health is associated with the loss of control, autonomy and independence, and it makes people aware of the approaching death. Asthma recorded the highest prevalence conditions with 3.4%, while Lung Disease recorded the least, 0.6 %.However, Depression, Oral health, and Injuries fairly recoded 1.4%, 2.5% and 1.8% respectively. Also, Ghanaians considered for the research tends heavily towards adults, and particularly older adults respectively. Most of the respondents belong to the Christian faith. There is fairly even distribution amongst males and females respectively. More than half of respondents were engaged in self-employment. Again, majority of the respondent belongs to the Akan ethnic group. In addition, Adult and Older Adult Ghanaians are likely to suffer lung disease as their younger adult counterparts. Ageing Ghanaians were likely to suffer asthmatic ailments as to their younger adults Ghanaians. Also, there is an indication that, older adults are likely to suffer depression and oral health conditions as to their young adults’ age category.Similarly, Ghanaians who are in other religious faith beside the stated ones do have lung disease as compared to the dominant Christian faith in Ghana.Interestingly, female respondents reported depression than their male respondents.Again, respondents who are employed in the various sectors of the economy indicated that, those who are in the private sector of employment were likely to suffer from lung disease as well as asthma. The Ga-Adangbe is 1.052 times as likely to be asthmatic as compared to their Akan tribes. In a related development, study by The Mary Anne Morgan, (2003) indicated that diseases like cancer, heart disease and asthma disproportionately affect low income, ethnically diverse communities as it is partly collaborated this study.There is an indication that, cohabiting, separated / divorced and widowed couples in Ghana do have a greater chance to be asthmatic and report oral health and well as depression diseases conditions than those who are currently married. The study however, did not support the assertion that Chronic diseases and poverty are interconnected in a vicious circle, (WHO 2005) whereas this study affirms that. Thus higher level of education and income quintiles are associated with lung disease, depression and injuries. Our study partly support the 1981 assessment of the health impact of various diseases in Ghana, ranked in order of healthy days of particular sedentary occupations and consumption of a wider diversity of local and foreign foods, the urban wealthy are not the only high risk groups for chronic diseases in Ghana.From the Table 3, the Model-Fit Statistics shows that the binary logistic regression model adequately fits the data, since in almost all cases the model likelihood ratio test (LRT) and the corresponding significance values or the p-values reported for each model was less than 5% level of significance.

5. Conclusions

- This paper revealed that, in Ghana, the occurrences of chronic disease conditions are associated with some socio-demographic/socio-economic factors: age, sex, religion, ethnicity, marital status, occupation, level of education, and income levels. Asthma recorded the highest prevalence conditions followed by Oral health; Injuries, Depression and Lung disease. The impact of these factors on chronic diseases need to be considered in formulating health policy on chronic diseases and its implementation in Ghana to save the country from the negative consequences on the health of Ghanaians.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- The World Health Organization (WHO) study on Global AGEing and Adult Health is the main source of the data.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML