-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Statistics and Applications

p-ISSN: 2168-5193 e-ISSN: 2168-5215

2013; 3(3): 50-58

doi:10.5923/j.statistics.20130303.03

Poverty Levels and Maternal Nutritional Status as Determinants of Weight at Birth: An Ordinal Logistic Regression Approach

Oladipupo B. Ipadeola1, Samson B. Adebayo2, Jennifer Anyanti3, Emmanuel T. Jolayemi4

1Malaria Action Program for States, Abuja, Nigeria

2National Agency for Food, Drug Administration and Control, Abuja, Nigeria

3Society for Family Health, Research and Evaluation Division, Abuja, Nigeria

4Department of Statistics, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Oladipupo B. Ipadeola, Malaria Action Program for States, Abuja, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

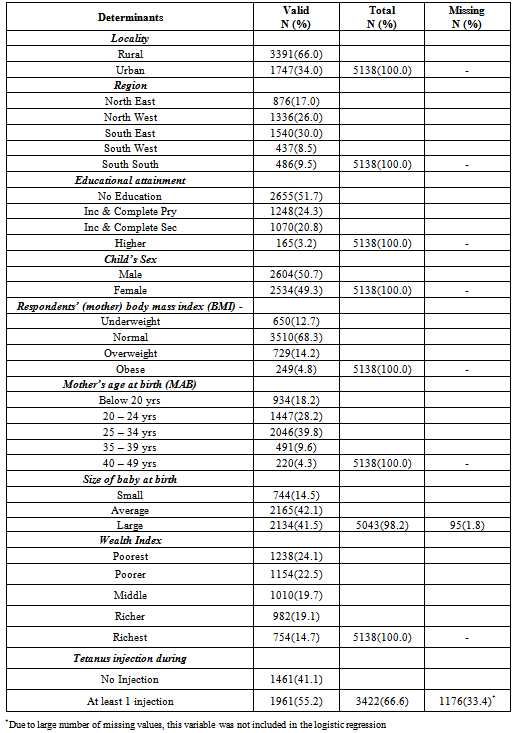

This paper explores the possible influence of household poverty levels and maternal nutritional status on child’s weight at birth. The 2003 Nigeria Demographic Health Survey (NDHS) measures weight at birth on an ordinal scale. Therefore, modelling techniques that take cognizance of ordinal responses are suitable for this situation. Ordinal logistic regression technique was employed for all analyses. Quintiles of wealth index were used as a measure of assets owned by households while body mass index was used to assess maternal nutritional status. Other demographic characteristics such as mother’s age at birth of the child, educational attainment, locality (urban/rural) and geo-political zones were controlled for in the models. The sample size for survey was 5138. Wealth index and maternal nutritional status were positively associated with child’s weight at birth, while mother’s educational attainment was not statistically significant. Significant and positive association of wealth index was evident with middle and richest when compared with those in the poorest category of wealth index. Mothers that were underweight are less likely to give birth to heavier children while those that were overweight or obese are more likely to give birth to children with heavier weights compared with mothers with normal BMI.

Keywords: Proportional Odds Ratio, Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey, Wealth Index, Cut-off Points, Cumulative Logistic Regression

Cite this paper: Oladipupo B. Ipadeola, Samson B. Adebayo, Jennifer Anyanti, Emmanuel T. Jolayemi, Poverty Levels and Maternal Nutritional Status as Determinants of Weight at Birth: An Ordinal Logistic Regression Approach, International Journal of Statistics and Applications, Vol. 3 No. 3, 2013, pp. 50-58. doi: 10.5923/j.statistics.20130303.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Child’s weight at birth has been shown to be associated with child’s and maternal health; which in turn could be a determining factor of maternal and child mortality before, during and after birth. This may also be related to many factors, both physical and physiological. Among such factors that have been investigated in the past were maternal and paternal weights and heights, ethnicity, gestational age, birth order, maternal education, mother’s age at the birth of child and race[1][2][3][4]. Other possible determinants of child’s weight at birth that have been considered in literature were: paternal education, socio-economic status, prenatal care, method of delivery (either normal or through caesarean), child’s sex, maternal smoking status, consumption of alcohol, and use of psychoactive drugs duringpregnancy[5][6][7][8][9]. It was observed that maternal weight had a greater influence on birth weight, while maternal and paternal height contributions were similar in nature[2]. Furthermore, weight and height of father and mother contributed equally to infant’s weight gain.Low birth weight (LBW) i.e. birth weight less than 2.5 Kilograms (KG), as a result of preterm birth or intrauterine growth retardation, is the strongest single factor associated with peri-natal, neo-natal, post-natal and infant mortality. Birth weight is related to health outcomes in childhood, such as neurological deficits and lower cognitive skills[10][11] as well as in adulthood; such as high blood pressure, diabetes, coronary heart disease and stroke[12][13][14][15]. LBW remains a substantial public health concern even in industrialized countries. It is more common among blacks than whites[16]. In addition, socio-economic factors have been suggested in literature[5][17]. Worldwide, it is estimated that 15.5% of all live birth per year are LBW, and more than 95% of LBW infants are born in developing countries[18]Birth weight is also an important determinant of weight gain after birth. While low birth weight is associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality in newborns and during infancy, excessive weight is associated with decreased maternal amino acids[19] Decreased foetal growth may result from a limitation in the nutrient supply to the foetus. Research has also linked small size at birth to increased risk of heart disease and diabetes later in life[15] In addition, poverty has been shown to be a determining factor of maternal and child health[20]. Findings from a study comparing siblings who were born with different weights and who experienced different economic circumstances at various points in their lives linked genetics and poverty as powerful factors in low birth weight. Findings from other studies have demonstrated that a combination of poverty and a family history of low birth weight significantly increase the likelihood that a baby will be born underweight.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

- The principal objective of the 2003 NDHS was to provide current and reliable data on fertility and family planning behaviour, child mortality, children’s nutritional status, the utilization of maternal and child health services, as well as knowledge and attitudes towards HIV/AIDS. A related objective was to provide as many of these key indicators as possible for urban and rural areas separately. The population covered by the 2003 NDHS was defined as the universe of all women aged 15-49 years and all men aged 15-59 years in Nigeria. A probability sample of households was selected and all women aged 15-49 years identified in the households were eligible to be interviewed. In addition, in a sub-sample of one-third of the households selected for the survey, all men aged 15-59 years were eligible to be interviewed[21].

2.2. Methods

- Consider a regression situation where the outcome variable on size of child at birth, say Yi, i = 1, …, n, is measured on an ordinal scale. A cumulative logistic regression model is suitable for this outcome. This is the most widely used model in ordinal regression. Suppose Yi has k categories together with a vector of discrete or continuous covariates xi. Marginal probabilities for Yi are related to vector of covariates xi by a cumulative logistic model

| (1) |

| (2) |

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Results

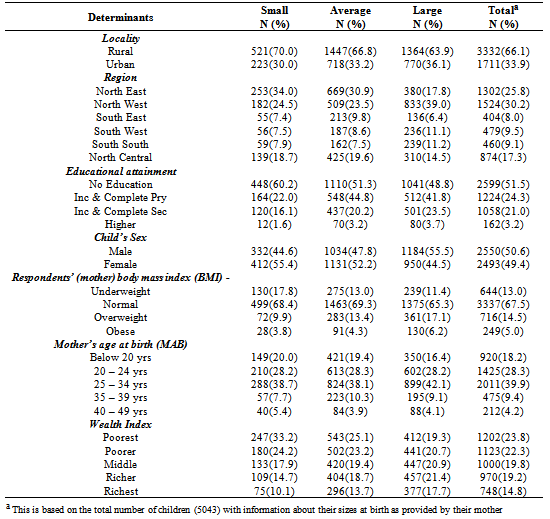

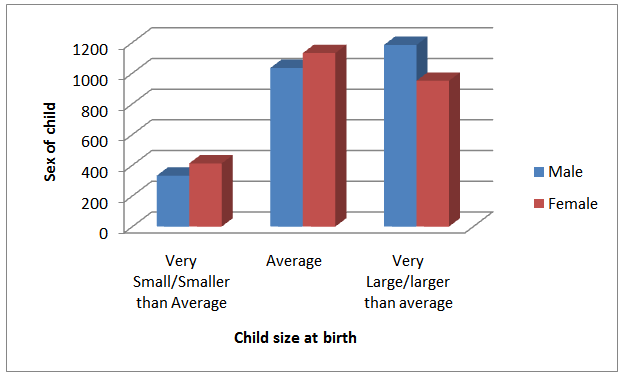

- The data shows that a larger proportion of female children were described to have weighed very small or smaller than average at birth compared with their male counterparts. Of the 5 138 children that were contained in this dataset, information on weight at birth was only available for 5 043 children. Almost 15% weighed below average and about 42% weighed above average while the remaining weighed about average. About seven in ten of the children domiciled in rural areas compared with slightly higher than three in ten in urban areas. More than half of the mothers (51.7%) had no formal education compared with less than 4% of mothers who had higher or tertiary education. The proportion of male and female children was approximately equal. Significant association was evidence between sex and child’s weight at birth (Chi=37.98, p=0.000). Figure 1 presents the distribution of age at birth desegregated by sex.

| Figure 1. Bar charts describing the distribution of Child's size at birth disaggregated by sex |

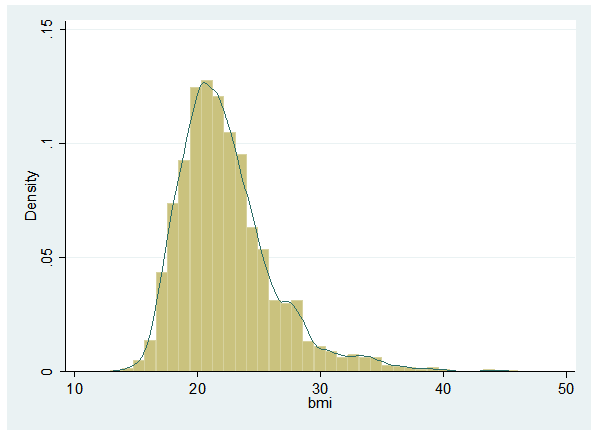

| Figure 2. Histogram showing the distribution of BMI with the Kernel density (line) super-imposed |

|

|

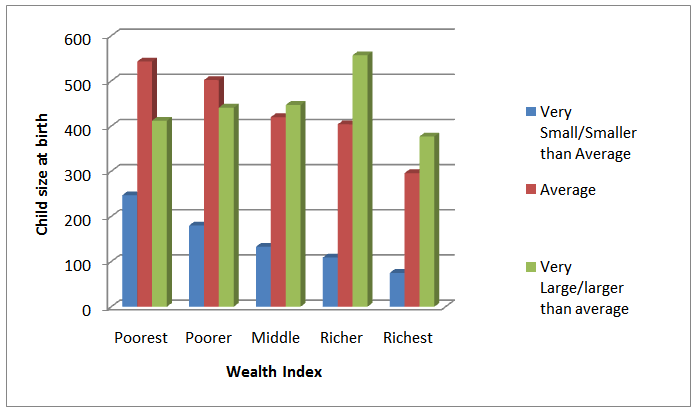

| Figure 3. Bar charts describing the distribution of Child's size at birth and Wealth Index |

|

|

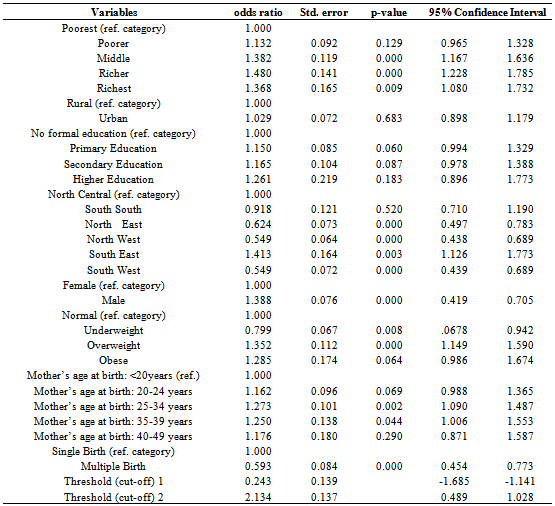

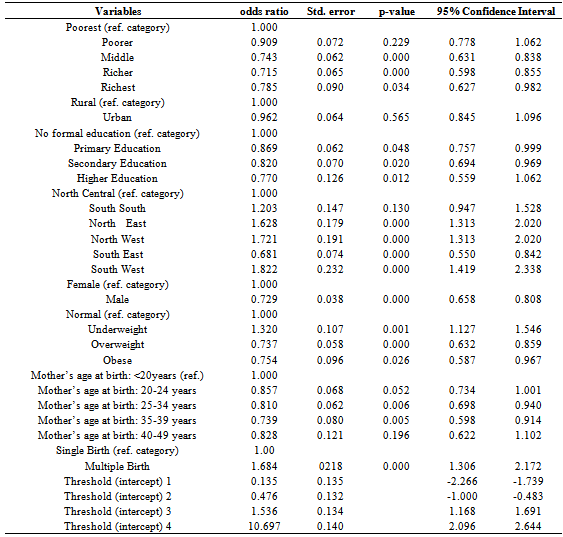

- Significant and positive association of wealth index was evident with middle (OR=1.38, p<0.0001), higher (OR=1.48, p= p<0.0001), and highest (OR=1.37, p=0.009) wealth quintiles when compared with those in the poorest category of wealth index. Respondents in the upper wealth quintiles are significantly more likely to give birth to children with large weight compared with those in the lower quintiles (p=0.009). Furthermore, mothers that were too thin or underweight based on their BMI, were more likely to give birth to children with low birth weight (OR=0.80, p=0.008); while those that weighed more than they should (overweight: OR=1.35, p<0.0001; or obese: OR=1.29, p=0.065) were more likely to give birth to children with large weights when compared with mothers with normal BMI. Significant gender differentials were also found. Males were about 1.4 times (p<0.0001) more likely to have weights larger than their female counterparts at birth. Gender bias in child’s weight at birth has been shown by other authors.Age of mother at the birth of a child has also been shown to be of risk to pregnancy outcomes. Teenage mothers were more likely to give birth to children with low birth weight. Here, positive significant association was observed for mothers’ age at birth and child’s weight at birth. Children from mothers in the age range 25 to 39 years were about 1.26 times more likely to weigh more at birth compared with children from teenage mothers (p<0.05). Significant spatial pattern was observed at the level of geopolitical zones with p<0.05. This spatial variation, however, needs to be investigated further at a highly disaggregated level of states as information at this level could be masked. Multiple births are significantly associated with low birth weight compared with singleton births (OR=0.59, p<0.0001). However, the effects of mother’s educational attainment and locality (rural/urban differential) were not significantly associated with child’s weight at birth.

3.2. Discussion of Results

- It was found that strong association exists between maternal and paternal educational attainment. Hence the inclusion of both variables resulted in multi-collinearity. Furthermore, inclusion of parity in the logistic regression models affected the significance of mother’s age at the birth of child. Therefore, we prefer to present findings for models where paternal educational attainment and parity were excluded. Gender bias in weight at birth has been previously reported by some authors. For instance, see[23][24][25][9] [8][26] and[27] Findings from this paper, therefore, corroborate other authors. Male children were more likely to be heavier at birth compared with their female counterparts. Research also found that increases in a family's financial ability to meet its basic needs were directly linked to birth weight. According to New York Times of 9th January, 2002, findings from research linked genetics and poverty as powerful factors in low birth weight. The study authors (Dalton Conley and Neil G. Bennett) also found that a child who was born underweight and whose formative years were spent in poverty is considerably less likely to graduate from high school on time compared with other children. Therefore, education reforms should include supplementary support to children who were born underweight. Findings from our paper also reveal that children born to mothers in high wealth quintiles are less likely to have low weight at birth compared with those born to mothers in low wealth quintiles. These findings also suggest the needs for public health organizations to identify infants who are at high risk for low birth weight, as well as ways for them to reduce or counteract that risk. The significant spatial effect in this paper reveals that there are substantial variations across all the six geo-political zones in terms of weight at birth of children according to the data from 2003 NDHS. Further investigation of such spatial variations should be properly explored so as to provide more insightful information for policy makers.

4. Conclusions

- This approach has provided the opportunity to explore relationships between ordinal responses and determinants of child’s weight at birth. Wealth index and maternal nutritional status were found to be significantly associated with child’s weight at birth. Mothers who belong to household with low wealth quintiles are more likely to give birth to children with lower birth weight. The state of maternal and child health is one indicator of a society’s level of development; as well as an indicator of the performance of the health care delivery system. As the country strive towards attaining universal comprehensive health care services for the citizens; especially for mothers and children, the issue of alleviating poverty is important. This has policy implications since a significant association exists between poverty and low birth weight. Health programmers need to design interventions to tackle both poverty and health simultaneously. Female children were disproportionately associated with low birth weight. Therefore, mainstreaming of gender issues into health policies is desirable. Findings from this paper will provide opportunity to enhance appropriate policy formulation on gender issues. To enhance proper child health’s policy formulation, efforts should be targeted at an analytical tool which is capable of exploring spatial variation at a highly disaggregated level of states. This is due to the fact that policies are rather made at state level rather than geo-political zonal level. Furthermore, there are no two states within the same zone jointly developing policies. Through this, one could get better understanding of the situation of child health at state level.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to acknowledge ORC Macro and the National Population Commission of Nigeria for making these data available online. Support of the other members of the Research and Evaluation Division of the Society for Family Health Nigeria on this manuscript is appreciated.

Conflict of Interest

- The authors declare no conflict of interest. Furthermore, no financial support was received for this work as the data used were secondary data.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML