-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2025; 15(2): 47-57

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20251502.03

Received: Oct. 9, 2025; Accepted: Nov. 3, 2025; Published: Nov. 14, 2025

A Mathematical Model Based on Pairwise Comparison and Genetic Algorithms to Assist Tennis Coaches of Non-professional Tennis Players

J. Werneck Allen1, Antonio Juarez S. M. de Alencar1, William A. Jr.1, Elisangela L. Faria1, 2, Marcelo P. Albuquerque2, Clecio R. Bom2, Paulo J. Russano2

1ImagineLabs Sports, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

2Brazilian Center for Physics Research (CBPF), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Correspondence to: Antonio Juarez S. M. de Alencar, ImagineLabs Sports, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper introduces a mathematical model that allows non-professional tennis players to be classified. As a result, it evaluates the shortest way to improve their performance. The model is based on expert opinion and genetic algorithms. A large variety of performance indicators are considered by the model. These indicators can be easily extended to accommodate the needs of players and their respective coaches. Expert opinion is captured using the pairwise comparison ideas that served as the basis for the development of Saaty’s Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). The model provides valuable insights to both coaches and tennis players.

Keywords: Pairwise comparison, AHP, Genetic algorithms, Tennis players, Tennis coaches, Coach assistance

Cite this paper: J. Werneck Allen, Antonio Juarez S. M. de Alencar, William A. Jr., Elisangela L. Faria, Marcelo P. Albuquerque, Clecio R. Bom, Paulo J. Russano, A Mathematical Model Based on Pairwise Comparison and Genetic Algorithms to Assist Tennis Coaches of Non-professional Tennis Players, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 15 No. 2, 2025, pp. 47-57. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20251502.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Throughout history, statistical analysis has been an important part of sports activities. Over time, amateur practitioners, professional players, coaches, and fans have relied on the analysis of performance indicators to identify the strong and weak points of individual athletes, the teams to which they belong, and their adversaries [1].The methods used in these analyses vary considerably. They include basic statistical calculations such as frequency, mean, standard deviation, and correlation [2], and more advanced methods, such as logistic regression [3], analysis of variance [4] and resampling [5].Over the last few decades, sport analytics has seen the addition of new methods and techniques coming from the decision-making research area, such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process [6], the Analytic Network Process [7], TOPSIS [8], and VIKOR [9]. Moreover, mathematics and computer science have also made their contribution to sports analytics with the introduction of methods such as fuzzy logic [10], random forest [11] and neural networks [12]. Dindorf et al. present a comprehensive discussion on the use of artificial intelligence in sports [13].Nevertheless, in recent years, new developments in computer vision and biometric wearables have allowed for a whole new set of performance indicators to be captured and analyzed in real time. By analyzing images captured by a camera, one can figure out an athlete’s reaction time, strength, ground speed, positioning, and strategy, among other skill indicators [14]. In addition, biometric wearables can be used to monitor an athlete’s vital signs, such as heart rate, blood pressure, stress level, and oxygen saturation [15].All of this has served as a basis to build computer applications that can capture and process information on the physical, tactical, and technical aspects of sports practice while these activities are taking place or immediately after. The processed information can be composed of general statistics of an athlete’s skills, the rank of athletes in accordance with their performance in sports events, and predictions about the results of tournaments. The Internet site Slashdot presents an extensive list of sports computer applications that are available on the market [16].This paper builds upon the current state of these computer applications. It presents a mathematical model based on the use of the pairwise comparison technique used by Saaty when building the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) [17]. The model uses the expert opinion of both coaches and professional tennis players to analyze the performance indicators frequently captured by tennis-monitoring computer applications. These indicators are then used to rate athletes’ skills and classify them into distinct categories. Only the athletes’ personal skills are considered by the classification process, i.e., it does not take into account the athletes’ performance in tournaments. This allows non-professional tennis players to be compared fairly to other players without the need to play tennis competitively. The shortest course of action for an athlete to ascend in the category hierarchy is provided with the support of genetic algorithms.

2. Background

2.1. Pairwise Comparison

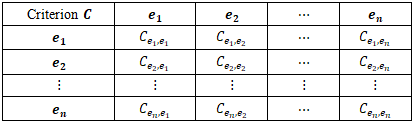

- Given a set of entities

and a criterion

and a criterion  , pairwise comparison is a preference prioritization process in which all the objects in

, pairwise comparison is a preference prioritization process in which all the objects in  are compared among themselves in respect to

are compared among themselves in respect to  . In the pairwise comparison process, two entities are compared at a time. These comparisons may be represented as an

. In the pairwise comparison process, two entities are compared at a time. These comparisons may be represented as an  matrix, where

matrix, where  is the result of comparing entity

is the result of comparing entity  with entity

with entity  , for

, for  See Table 1 in this respect.

See Table 1 in this respect.

|

is consistent, then

is consistent, then  yields a comparison result that is the reciprocal of the result yielded by

yields a comparison result that is the reciprocal of the result yielded by  . For example, if the criterion in place is height and Peter is much taller than John, then John is much shorter than Peter. It should be noted that

. For example, if the criterion in place is height and Peter is much taller than John, then John is much shorter than Peter. It should be noted that  is the result of comparing an object with itself and, consequently, the comparison result and its reciprocal are the same. For instance, in respect to height, Peter is the same height as himself. The use of pairwise comparison in science is due to the work of the psychometrician L. L. Thurstone at the beginning of the 20th century [18]. An introduction to pairwise comparison is presented in [19]. Recent Advances in pairwise comparison can be found in [20].

is the result of comparing an object with itself and, consequently, the comparison result and its reciprocal are the same. For instance, in respect to height, Peter is the same height as himself. The use of pairwise comparison in science is due to the work of the psychometrician L. L. Thurstone at the beginning of the 20th century [18]. An introduction to pairwise comparison is presented in [19]. Recent Advances in pairwise comparison can be found in [20].2.2. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

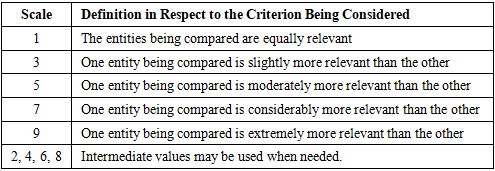

- The AHP is a decision-making method that has been conceived to derive ratio scales from the elements of a given set of entities by making extensive use of pairwise comparison [17]. The ratio scales reflect the relative strength of preferences of one entity over another. The entities being compared may be evaluated by criteria based on abstract perceptions of reality, such as beauty, comfort and safety, and of concrete nature, such as height, weight, and speed. In the AHP, several criteria may be combined to rank the preferences among entities. To facilitate reasoning and avoid inconsistencies, such a combination of criteria is organized in a hierarchy. At the top of the hierarchy, one finds the overall objective to be reached. For example, to select the best player amongst a group of tennis players.The intermediate levels consist of the criteria and sub-criteria to be considered when ranking preferences among entities. For instance, the skills of tennis players may be compared using criteria such as technical skill, physical capacity, and tactical ability. Finally, at the bottom of the hierarchy reside the entities to be ranked. For example, the actual tennis players. In the AHP jargon, these entities are called “alternatives”.In the AHP, the result of comparing entities is evaluated with the support of a comparison scale. Table 2 shows a simplified form of this scale, as proposed by Saaty in [17].

|

is represented as the

is represented as the  matrix shown on the left part of Table 1. It should be noted that because the comparison scale presented in Table 2 is used, the elements on the diagonal of the

matrix shown on the left part of Table 1. It should be noted that because the comparison scale presented in Table 2 is used, the elements on the diagonal of the  matrix are all equal to 1, i.e.

matrix are all equal to 1, i.e.  is 1.

is 1. 2.3. An Example

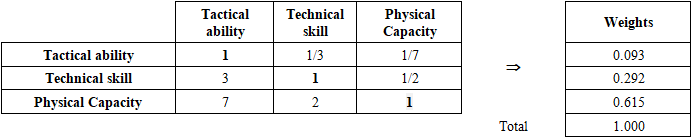

- For example, consider that a group of non-professional tennis players is to be ranked according to their tactical ability, technical skill, and physical capacity. Table 3 presents an AHP comparison matrix used to determine the relative importance of these indicators to play tennis. In general, matrices like this are based on the opinion of a group of coaches and professional tennis players. See the acknowledgements part of this article in this regard.

|

is the normalized eigenvector associated with the highest eigenvalue of the

is the normalized eigenvector associated with the highest eigenvalue of the  matrix, i.e.

matrix, i.e.  In the example presented in Table 3, the vector “Weights” is this eigenvector. It should be noted that it expresses the relative importance of those skills, abilities and capacity in the form of numerical values. The higher the numerical value, the more important the indicator is.Because inconsistencies may arise during the comparison process, Saaty proposes a consistency rate =

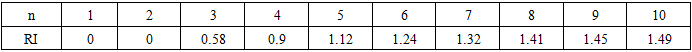

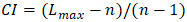

In the example presented in Table 3, the vector “Weights” is this eigenvector. It should be noted that it expresses the relative importance of those skills, abilities and capacity in the form of numerical values. The higher the numerical value, the more important the indicator is.Because inconsistencies may arise during the comparison process, Saaty proposes a consistency rate =  , where

, where  , the consistency index is given by

, the consistency index is given by and

and  , the random consistency index, is obtained from Table 4.

, the random consistency index, is obtained from Table 4.

|

, otherwise the decision makers must revise their decisions [21]. The CI, RI and CR of the comparison matrix presented in Table 3 are respectively 0.002, 0.58 and 0.32%. Therefore, no revisions of previously made decisions are necessaryOver the years, an extensive bibliography has been developed around the Analytic Hierarchy Process, and many articles and books have been published in the scientific and business areas [22]. An introduction to the AHP can be found in [23,24].

, otherwise the decision makers must revise their decisions [21]. The CI, RI and CR of the comparison matrix presented in Table 3 are respectively 0.002, 0.58 and 0.32%. Therefore, no revisions of previously made decisions are necessaryOver the years, an extensive bibliography has been developed around the Analytic Hierarchy Process, and many articles and books have been published in the scientific and business areas [22]. An introduction to the AHP can be found in [23,24].2.4. The AHP and Pairwise Comparison in the Practice of Tennis

- Both the AHP and pairwise comparison are not strangers to the art of tennis. Over time, they have been used extensively to rank and pinpoint promising tennis players and make predictions about the outcome of tennis matches.For example, Bozóki, Csató, and Temesi [25] use incomplete pairwise comparison matrices to rank professional tennis players who have been at the top of the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) rank over the last 40 years. In their work, the eigenvector [17] and the logarithm least squares method [26] are used to figure out the weights of the incomplete matrices. An important aspect of Bozóki, Csató and Temesi’s work is that it does not require that all players have faced each other on the court. In [27], Temesi, Szádoczki and Bozóki adopt a similar approach to rank top women tennis players.Garcia and Mori apply pairwise comparisons to help identify the greatest tennis players of all time or GOAT [28]. Data from the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) and the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) is used to select the male and female greatest players. Not surprisingly, well-known players such as Serena Williams, Steffi Graf, and Martina Navratilova come at the top of the women GOAT’s list and Novak Djokovic, Roger Federer, and Rafael Nadal at the top of the male list.In [29] Wu employs the AHP and statistical tests [30] to quantify momentum in tennis matches. His work shows that, in mathematical terms, momentum can be defined as the probability of scoring or losing a point as a function of the outcome of the preceding point. In addition, Wu’s findings refute the long-held belief that performance fluctuations in tennis matches are random events. As a result, it is up to coaches to better prepare their athletes to create and maintain favorable momentum.The AHP, XGBoost [31] and genetic algorithms [32] are utilized by Kang et al. to enhance tennis match predictions [33]. Their article uses the AHP to identify key factors influencing momentum in matches. Subsequently, the weights of these factors are optimized using XGBoost and genetic algorithms with the goal of improving the accuracy of predictions.Hraste, Đurovié and Stanišié rely on the AHP to explain the decision-making priorities of offensive tennis players when they are playing offensively and defensively. The relative importance of these priorities is based on the opinion of seven coaches who stand out on the world circuit. By being aware of these decision-making priorities, coaches can better prepare their athletes for the challenges of tennis matches and tournaments [34].Zang et al. [35] combine AHP with the entropy weighted method [36], TOPSIS [8], and principal component analysis [37] to predict tennis players’ scoring ability based on their performance during a match in real time. As a result, the prediction accuracy of women's tennis matches surpassed 0.95 in major tournaments.Lei, Lin and Cao Jr. bring together the AHP and support vector machine (SVM) [38] to predict the outcome of professional tennis matches. The resulting model was tested using data from the Wimbledon Championship 2023. Their model has reached an accuracy of over 0.83 when predicting the winner of male professional matches. Furthermore, the authors claim that their model is more accurate than existing models in predicting the winner of a point [39].Regardless of having the largest population in the world, China lacks world-class professional tennis players [40]. Guangfu and Kanchanathaweekul have devised a way to help tackle this problem. In [41], they explore the use of the AHP to identify talented young tennis players in the country. By proving the means to distinguish these athletes from the regular players, they expect talented tennis players to receive the necessary support from the Chinese government. As a result, the presence of Chinese athletes in the international circuit may increase substantially.Despite the vast literature that has connected pairwise comparison and the AHP to the art of tennis, very little has been done to suggest what actions non-professional players should undertake to improve their performance. This article goes towards filling this gap.

2.5. Genetic Algorithms

- Genetic algorithms are a family of mathematical optimization methods inspired by the selection process widely observed in nature. The optimization begins by randomly creating an initial population of individuals in the potential solution space. It proceeds by refining this population interactively using selection, crossover, and mutation processes. In each interaction, a population of better-fit individuals is created until a satisfactory solution is found.In this context, a fitness function is used to indicate how well an individual performs with respect to the optimization objective. By using the fitness function, the selection process chooses the fittest individuals in the population to parent the next generation. In general, this process is probabilistic, where the best-fit individuals have a higher chance of being selected.In genetic algorithms, the characteristics of individuals who are the potential solution to the problem at hand are often encoded as a sequence of 0s and 1s. These sequences are frequently referred to as the individuals’ chromosomes.In the crossover process, the chromosomes of two individuals are combined to produce an offspring. This simulates the natural process of reproduction, where the good characteristics of two individuals are combined to yield a better-suited offspring.The mutation action allows small changes to the characteristics of individuals to be introduced randomly. This allows new areas of the solution space to be considered while helping to prevent the optimization process from being trapped in a local optimal solution.Although genetic algorithms are the result of contributions of several researchers over time, John H. Holland is credited with the development of this family of optimization methods in the late 1970s and for its popularization [49]. An introduction to Genetic Algorithms can be found in [48].

3. The Model

- The following steps have guided the development of the models proposed in this article: 1. Assembling experts in the art of tennis and coaching.2. Gathering the data and the metadata.3. Identifying the criteria and sub-criteria used to build the classification model.4. Defining the scale to evaluate each sub-criterion and the set of alternatives.5. Building the model.6. Presenting suggestions on what actions non-professional tennis players should take to improve their performance.

3.1. Assembling Experts

- A group of experts was assembled to support the development of the model presented in this article. These experts were selected from experienced tennis players with relevant national and international experience. All of them are involved with tennis in the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, including activities that help others to improve their technical tennis skills and tactical abilities.This group of experts was asked to help develop a mathematical model capable of classifying non-professional tennis players into categories. Furthermore, this model should be able to provide players with a clear path on how to improve their skills, abilities, and physical capacity step by step. These experts are listed in the acknowledgements section of this article.

3.2. Gathering the Data and Metadata

- ImagineLabs (IL) [42] is a startup company based in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Over the last 14 months IL has been developing a monitoring and training analysis app for tennis. It is called TotalTennis [43]. At this point, hundreds of thousands of video frames have been captured and analyzed by the app, using computer vision and various artificial intelligence models and machine learning algorithms. As a result, a number of statistics have been gathered and made available to support the writing of this article. These are comprised of statistics about point, set and game disputes, such as duration, score tracking, number of balls exchanged, the height, trajectory and speed of the ball, variety of shot types, hit point of the ball on the court, distance covered by each player, position of the player on the court, balance of each player, and players’ reaction time, among others.

3.3. Identifying the Criteria and Sub-criteria

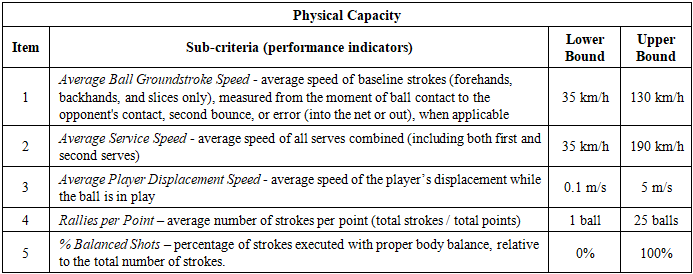

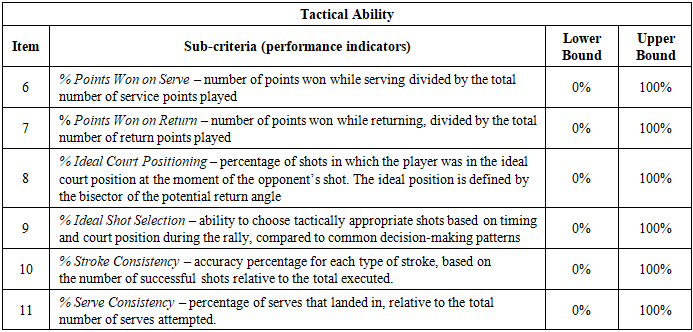

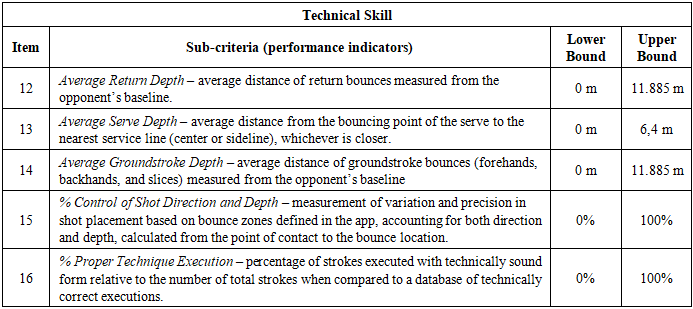

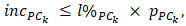

- Based on the data available for analysis and the goal established to build the model introduced in this article (see Item 3.1), the aforementioned group of experts devised the criteria and sub-criteria to be used for pairwise comparison. These criteria are shown in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7.Even in training, it is well known that it takes two players to play a game of tennis, i.e. the player of interest and his or her adversary. This designation is obviously arbitrary. Any of the players can be designated as the player of interest. Nevertheless, for the purpose of the model developed in this article, the criteria and sub-criteria presented in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 always refer to this player.It should be observed that each sub-criterion takes a value in a certain numerical interval. Some of these intervals are percentages, while others are not. Nevertheless, to facilitate reasoning, when one of those non-percentage criteria takes an actual value, it is transformed into a percentage value. Let

be one of those values. In this case

be one of those values. In this case  , the corresponding percentage value is given by

, the corresponding percentage value is given by  , where

, where  is the upper bound of sub-criterion

is the upper bound of sub-criterion  Furthermore, if

Furthermore, if  the lower bound of criterion

the lower bound of criterion  then

then  assume the value of

assume the value of  In addition, if

In addition, if  , then

, then  assume the value of

assume the value of  .It is important to note that for most of the criteria presented in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7, the closer a value is to their respective upper bound, the better. However, this does not apply to sub-criteria 12, 13, and 14, the average return depth, average serve depth, and average groundstroke depth, respectively.On a tennis court, the white line that runs parallel to the net at the rear boundary of both sides is called the baseline. Similarly, the white line that runs horizontally close to the net is called the service line, which is delimited by two sidelines forming a rectangle, called the service box. There are two service boxes on each side of the tennis court.During an exchange of balls between players (i.e., a rally), placing the ball close to the baseline is generally considered a strategic play. It forces one’s opponent farther back, reducing his or her offensive options. As a result, this helps to gain control over the rally and increase the probability of scoring points. The same line of reasoning can be applied during service. The closer a ball bounces to any of the lines delimiting the service box, the better. For balls bouncing inside the service box, sub-criterion 12 is the average distance from the bouncing point to the nearest line of the box.In tennis jargon, 0 meters to the baseline or the lines of the service box indicates that a ball hit one of those lines. If the distance is greater than 0 and smaller than the sub-criteria upper bound, it bounced inside the court limits; otherwise, it is out. Therefore, for sub-criteria 12, 13, and 14, the closer a value is to their lower bound, the better. As a result, to simplify matters, with respect to these sub-criteria,

.It is important to note that for most of the criteria presented in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7, the closer a value is to their respective upper bound, the better. However, this does not apply to sub-criteria 12, 13, and 14, the average return depth, average serve depth, and average groundstroke depth, respectively.On a tennis court, the white line that runs parallel to the net at the rear boundary of both sides is called the baseline. Similarly, the white line that runs horizontally close to the net is called the service line, which is delimited by two sidelines forming a rectangle, called the service box. There are two service boxes on each side of the tennis court.During an exchange of balls between players (i.e., a rally), placing the ball close to the baseline is generally considered a strategic play. It forces one’s opponent farther back, reducing his or her offensive options. As a result, this helps to gain control over the rally and increase the probability of scoring points. The same line of reasoning can be applied during service. The closer a ball bounces to any of the lines delimiting the service box, the better. For balls bouncing inside the service box, sub-criterion 12 is the average distance from the bouncing point to the nearest line of the box.In tennis jargon, 0 meters to the baseline or the lines of the service box indicates that a ball hit one of those lines. If the distance is greater than 0 and smaller than the sub-criteria upper bound, it bounced inside the court limits; otherwise, it is out. Therefore, for sub-criteria 12, 13, and 14, the closer a value is to their lower bound, the better. As a result, to simplify matters, with respect to these sub-criteria,  is calculated as

is calculated as  . As a result, for all sub-criteria introduced in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7, the closer their values are to their upper bound the better.

. As a result, for all sub-criteria introduced in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7, the closer their values are to their upper bound the better.

|

|

|

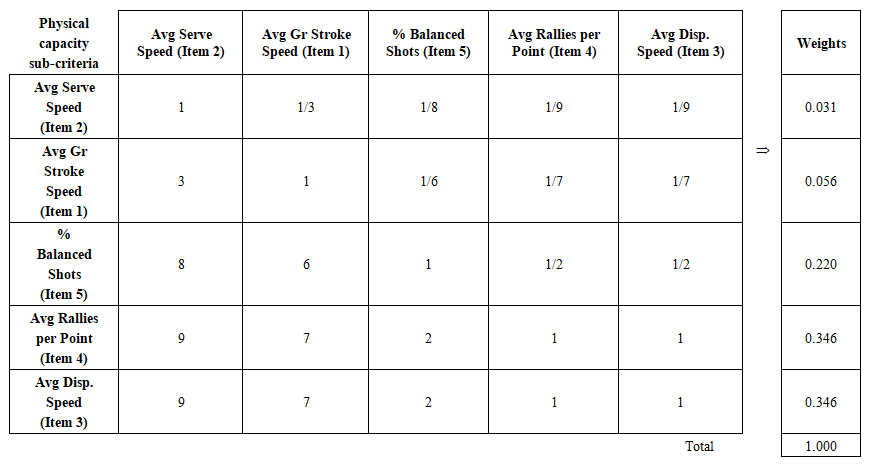

3.4. Defining the Weights Used to Evaluate Each Sub-Criterion

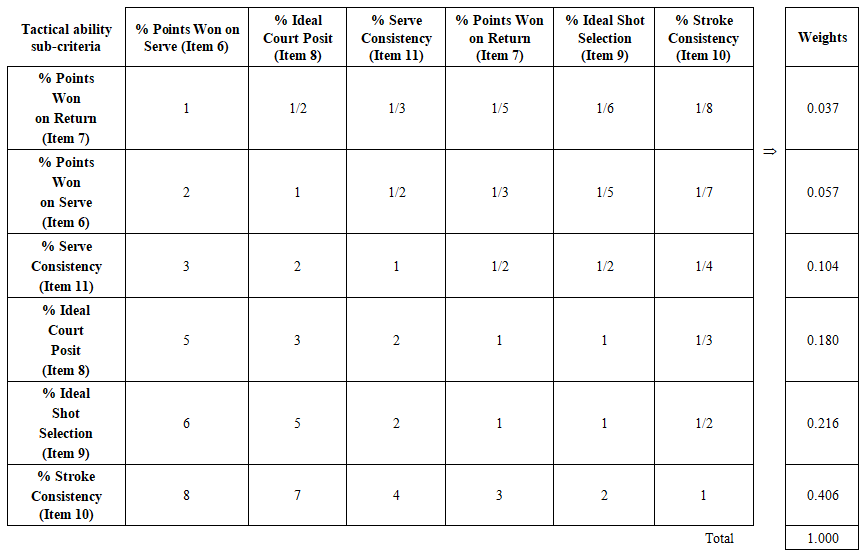

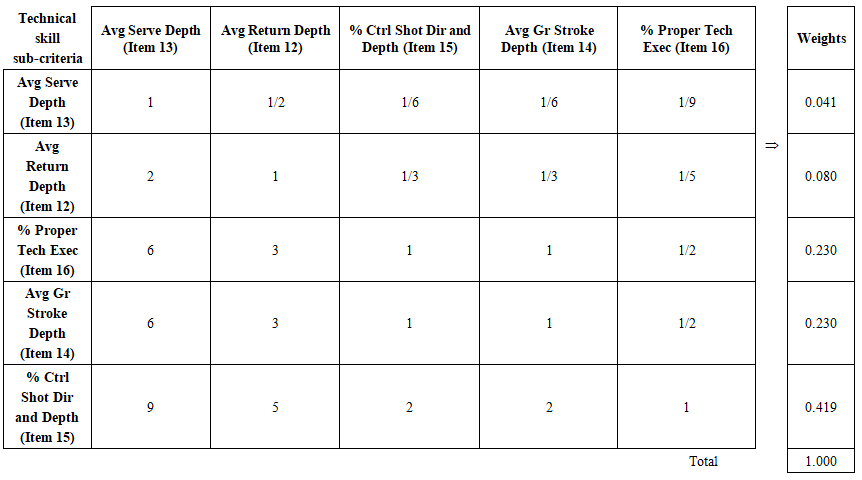

- The relative importance of the tactical ability, technical skill and physical capacity criteria is presented in Table 1, see column “Weights” in this respect. The relative importance of the corresponding sub-criteria are presented in Table 8, Table 9, and Table 10.

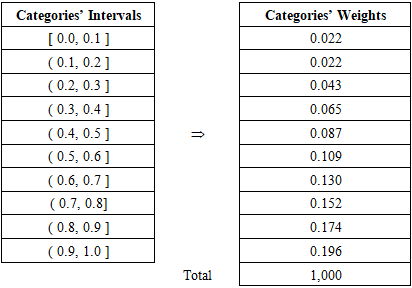

3.5. Defining the Weights Used to Evaluate the Set of Alternatives

- As indicated in Item 3.3, the alternatives’ rates take value in the [0, 1] interval. Following the ideas of [44,45,46] on the use of absolute measurement in the AHP, the alternatives’ rates are grouped into categories. Column “Categories’ Intervals” of Table 11 shows these categories. They were determined based on the consensual opinion of the experts cited in Item 3.1. Those categories are considered effective in distinguishing between low-performing tennis players and those with intermediate or advanced skill levels. Next, the weights of the categorized rates are obtained for each sub-criterion using pairwise comparison and the AHP. It was found that the weights attributed to those categories follow a near-linear scale.There is no clear evidence that each individual sub-criterion would necessarily require a different set of weights. As a result, Occam’s simplicity principle is used [47] and the same weights are used to rate all the alternatives with respect to the same set of sub-criteria. Column “Categories’ Weights” of Table 11 introduces these weights.

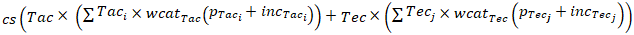

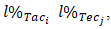

3.6. Building the Model

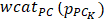

- Let

and

and  be the weights attributed to tactical ability, technical skill, and physical capacity criteria, respectively, as presented in Table 3. Moreover, allow•

be the weights attributed to tactical ability, technical skill, and physical capacity criteria, respectively, as presented in Table 3. Moreover, allow•  be the weight attributed to the i-th tactical ability sub-criterion,•

be the weight attributed to the i-th tactical ability sub-criterion,•  be the weight associated to the j-th technical skill sub-criterion and•

be the weight associated to the j-th technical skill sub-criterion and•  be the weight given to the k-th physical capacity sub-criterion,as introduced in Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10. Furthermore, let•

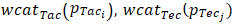

be the weight given to the k-th physical capacity sub-criterion,as introduced in Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10. Furthermore, let•  and

and  be the percentage scores given to a player

be the percentage scores given to a player  of interest as calculated by a monitoring and analysis app for tennis, for example, the “TotalTennis” app, and•

of interest as calculated by a monitoring and analysis app for tennis, for example, the “TotalTennis” app, and•  and

and  be the weights calculated for the category and sub-criterion into which

be the weights calculated for the category and sub-criterion into which  and

and  are grouped. See Table 11 in this regard.In these circumstances, the total score attributed to a tennis player

are grouped. See Table 11 in this regard.In these circumstances, the total score attributed to a tennis player  , i.e.

, i.e.  , is given by

, is given by

3.7. An Example

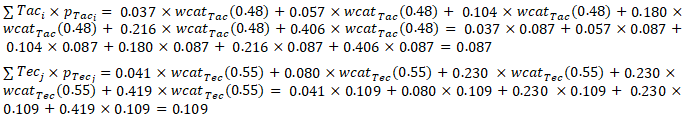

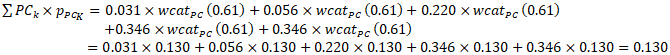

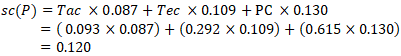

- To simplify matters, consider that all

= 0.48,

= 0.48,  = 0.55 and

= 0.55 and  = 0.61. Therefore, in these circumstances:

= 0.61. Therefore, in these circumstances:

| Table 8. The weights of the physical capacity sub-criteria (CR = 6.72%) |

As a result,

As a result,

| Table 9. The weights of the tactical ability sub-criteria (CR=1.43%) |

| Table 10. The weights of the technical skill sub-criteria (CR = 1,43%) |

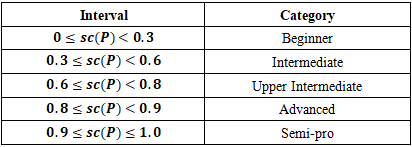

3.8. Defining the Players’ Categories

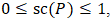

- Because

every player whose performance is evaluated by the model presented in this article is rated in that interval. As a result, the group of experts (see Item 3.1 in this respect) devised a set of categories in which tennis players are placed according to their skill, ability and capacity. Table 12 shows these categories.

every player whose performance is evaluated by the model presented in this article is rated in that interval. As a result, the group of experts (see Item 3.1 in this respect) devised a set of categories in which tennis players are placed according to their skill, ability and capacity. Table 12 shows these categories.3.9. Presenting Suggestions

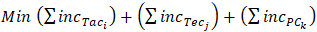

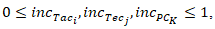

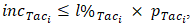

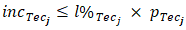

- To present suggestions on what a tennis player should do to reach the next category, it suffices to resolve the following optimization problem:

| (1) |

•

•

and•

and•  •

•  and

and  are the weights defined in Table 3,•

are the weights defined in Table 3,•  and

and  are the weights defined in Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8,•

are the weights defined in Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8,•  and

and  are the percentage rates attributed to a player of interest,•

are the percentage rates attributed to a player of interest,•  and

and  are the categorical weights attributed to a player of interest as introduced in Table 11,•

are the categorical weights attributed to a player of interest as introduced in Table 11,•  is the lower bound value of the category immediately higher than that of the player of interest. and•

is the lower bound value of the category immediately higher than that of the player of interest. and•  and

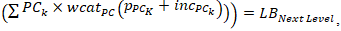

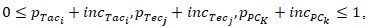

and  are the suggested rate increments that the player of interest should achieve or surpass to enter that category.This optimization problem can be solved with the use of genetic algorithms [48]. In the example introduced in Item 3.6, the player of interest is rated at 0.57. Therefore, according to Table 12, he or she is an “Intermediate”. When the system of equations presented above is applied to the player’s performance indicators, it shows that a mere average increase of 3.25% in the performance indicators presented in Table 5 is enough for he or she to move to the next category.With the intention of avoiding asking too much effort from a tennis play in just one step, the suggested increments

are the suggested rate increments that the player of interest should achieve or surpass to enter that category.This optimization problem can be solved with the use of genetic algorithms [48]. In the example introduced in Item 3.6, the player of interest is rated at 0.57. Therefore, according to Table 12, he or she is an “Intermediate”. When the system of equations presented above is applied to the player’s performance indicators, it shows that a mere average increase of 3.25% in the performance indicators presented in Table 5 is enough for he or she to move to the next category.With the intention of avoiding asking too much effort from a tennis play in just one step, the suggested increments  and

and  can have their contribution limited with the introduction of the following restrictions: •

can have their contribution limited with the introduction of the following restrictions: •  •

•  and •

and •  where

where  and

and  are percentage limits imposed on each of the sets of sub-criteria.Moreover, these limits can be used to select the kind of suggestions that one is willing to present to the player of interest. For example, if both

are percentage limits imposed on each of the sets of sub-criteria.Moreover, these limits can be used to select the kind of suggestions that one is willing to present to the player of interest. For example, if both  and

and  are set to zero and

are set to zero and  is set to a number higher than that, the system of equations would be allowed to present only technical skill improvement suggestions. The same line of reasoning can be used to present only physical capacity or tactical ability improvement suggestions.

is set to a number higher than that, the system of equations would be allowed to present only technical skill improvement suggestions. The same line of reasoning can be used to present only physical capacity or tactical ability improvement suggestions.

|

|

4. Conclusions

- Mobile phone apps such as TotalTennis have opened a whole new door to the monitoring and analysis of tennis matches. The variety and amount of data made available by these tools are extensive. It surpasses by far the data that can be gathered by manual means. Furthermore, the precision with which this data is collected is considerable and cannot be matched by those means. All of this is made possible by the use of computer vision and a wide range of artificial intelligence models and machine learning algorithms. As these apps are essentially low-cost tools, any non-professional tennis player can have their skills, abilities and capacity evaluated. They do not even need to participate in tournaments. By classifying non-professional tennis players into categories, these apps can provide a clear vision of the progress that players have made so far. In addition, they can provide suggestions on how they could improve their skills. Furthermore, one can choose to make suggestions selectively with respect to tactical abilities, technical skills, and physical capacity. Therefore, the model presented in this article, combined with an app to monitor and analyze tennis matches, can be used as an efficient coaching assistant. It helps coaches to devise a series of exercises that their athletes should execute to improve their performance more effectively.

5. Future Work

- At the same time as presenting a mathematical model that guides the training activities of tennis players, it also provides a basis for future research opportunities.For example, an experiment involving a large number of non-professional tennis players can be used to evaluate the model's precision and accuracy. This offers an opportunity to compare the opinion of the experts who helped to develop the model presented in this article with empirical data. Such an experiment would allow the weights attributed to criteria and sub-criteria to be adjusted so that the model’s classification accuracy and precision are maximized.Moreover, a large amount of data may indicate that a similar model must be developed to help very young tennis players improve their performance, as they are still developing motor coordination, strength, and tactical awareness, and might have specific needs and expectations.Sports-monitoring apps are becoming increasingly available. It is worth investigating how the same steps presented in this article can be used to classify athletes from related sports into categories and support the development of training programs that help to improve their performance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We thank the professionals listed below for actively supporting the development of the model presented in this article. Clayvert Gusmão, Isac Gomes, Alexandre Cury and Jorge Werneck Allen played a key role in the construction of the model, while Bruno Cruz played a supporting role.• Clayvert Gusmão is a prominent tennis player. He was number 1 in the Brazilian veterans ranking for 15 consecutive years (2007-2021) and number 1 in the world veteran ranking in 2009. He led the South American ranking for 7 years and is a three-time South American individual champion. He has won 331 titles in 6 countries and has attended renowned tennis education institutions such as the Sanchez-Casal Academy, the Brazilian Tennis Confederation (CBT) and the United States Professional Tennis Registry (USPTR). He has been working as a professional tennis coach for the last 30 years. Gusmão, a graduate in Business Administration, is well known for organizing tournaments and developing the art of tennis in Brazil.• Bruno Cruz is a tennis enthusiast who has been training to become a professional coach with the Brazilian Tennis Confederation (CBT). Currently, he is interning under Clayvert Gusmão’s supervision to gain the necessary experience to become a successful tennis coach. He holds a B.Sc. in Actuarial Sciences and has been advising Gusmão on the use of advanced statistical methods to analyze tennis matches and increase players’ performance.• Alexandre Cury is a distinguished tennis player and coach. As a youth player, he was the Rio de Janeiro state champion in the under-12 (US12), under-14 (US14) and under-16 (US16) categories, runner-up in the Brazilian junior singles championship and national junior doubles champion. By the end of his junior career, he was ranked in the top 10 in Brazil in under-18 doubles and in the top 12 in singles. In the United States, he won the Kansas high school state championship representing Iola High School in 1998. From 2001 to 2005, he played for Francis Marion University ranked in the top 6 in NCAA Division 2 at the time. Cury began coaching at age 17 with children in Iola and spent subsequent summers working at Pine Forest Camp (Pennsylvania) and Point O'Woods (Long Island), giving private lessons and conducting clinics for juniors and adults. In Brazil, he has been teaching social tennis for the past six years.• Isac Gomes is a professional tennis coach for high-performance players with almost a decade of professional experience. He started playing tennis at a very early age. Gomes was ranked number 1 in Argentina in the under-16 category (US16) and number 3 in the under-18 category (US18). He played interclub competitions in France, Italy, Germany, and Switzerland for 8 years. He holds international coaching certifications from the Sánchez-Casal Academy and Tennis Europe (the European tennis federation). For 12 years he trained at the Tandil Tenis Club (TTC) in Argentina, where he worked alongside players like Juan Mónaco, Juan Martín del Potro, Diego Junqueira, and Gabriela Sabatini.• Jorge Werneck Allen is an experienced tennis player who has been playing the sport for the past 17 years. He has participated in both the Brazilian circuit and international tournaments in France. A lifelong dedication to tennis has driven his pursuit of excellence in understanding the game and guiding others in their development. Allen holds a bachelor’s degree in Civil Engineering, a master's degree in Finance, and is currently pursuing a PhD in Economics at the Getulio Vargas Foundation, a leading educational and research institution in Brazil.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML