-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2024; 14(1): 5-12

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20241401.02

Received: Mar. 5, 2024; Accepted: Mar. 20, 2024; Published: Mar. 26, 2024

The Relationship Between Body Image Inflexibility and Female Collegiate Athletes Strength and Conditioning Habits

Braden Goimarac, Marcus M. Lawrence, Mark DeBeliso

Southern Utah University, Cedar City, Utah, USA

Correspondence to: Mark DeBeliso, Southern Utah University, Cedar City, Utah, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Body image negativity affects several populations including female athletes. A type of body image negativity is body image inflexibility: the inability or unwillingness to experience negative appearance-related thoughts and emotions. Purpose: The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between body image inflexibility and strength and conditioning habits among NCAA Division 1 (D1) female athletes. Methods: A Qualtrics powered survey was provided to willing D1 female athletes via QR code. The survey consisted of 14 questions, measuring body image inflexibility via the Body Image-Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (BI-AAQ) as well as strength and conditioning (SC) habits through two other structured questions. Participants completed the survey in the location of their choosing. The SC habits were categorized as yes or no for: “Have you ever missed a SC session because you wanted to avoid negative thoughts and emotions regarding your body image?”, and “Have you ever WANTED to miss a strength and conditioning session because you wanted to avoid negative thoughts and emotions?”. Results: During the research period 50 participants responded to the survey (M=37.3, SD=16.3). Twenty-six participants scored from 12-36 on the BI-AAQ while 4 scored in the 60-84 range. A Fisher’s Exact test suggested that there was no significant relationship between BI-AAQ scores and SC session attendance (p=1.00) or wanting to miss a SC session (p=0.28). Conclusion: While 66% of the D1 female collegiate athletes in this study have wanted to miss a SC session to avoid negative thoughts and emotions regarding their body image, there was no significant (or meaningful) relationship between BI-AAQ scores and missing a SC session or wanting to miss a SC session.

Keywords: Body Image Inflexibility, Strength and Conditioning Sessions, Female Athletes

Cite this paper: Braden Goimarac, Marcus M. Lawrence, Mark DeBeliso, The Relationship Between Body Image Inflexibility and Female Collegiate Athletes Strength and Conditioning Habits, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2024, pp. 5-12. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20241401.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Body image negativity is a growing concern among many populations throughout the world and is highly prevalent among female collegiate athletes with 54.4% of female athletes dissatisfied with their weight and close to 90% believing that they are overweight [1]. Before these numbers were known and understood, Kerrie Kauer and Vikki Krane interviewed 15 athletes as part of an investigation into how female athletes interpreted and reacted to the stereotypes ascribed to them [2]. One of the largest stereotypes they felt they were identified by was that they were “masculine.” In response to this masculine stereotype, the athletes reacted by attempting to distance themselves from their athletic identity and trying to act more feminine. Female athletes face a myriad of both internal and external pressure regarding their bodies, wishing they could change their appearances while also managing the external opinions of others regarding their appearances [3]. In its simplest terms, body image is defined as one’s perceptions and attitudes in relation to one’s own physical characteristics [4]. So, by default body image is not necessarily a negative concept although it commonly carries that connotation. Body image negativity arises when there is a discrepancy between an ideal and an individual’s belief that they do not currently live up to that ideal [5]. So, the more unrealistic the ideal, then the more likely body image negativity is to occur. For females, this becomes especially problematic as a generalization the ideal body size is far smaller than the average woman [6].The ability to openly experience these negative thoughts and emotions about the body without acting on or trying to change them is called body image flexibility [7]. It is the ability to embrace all thoughts and emotions an individual may have regarding their body. This embrace allows them to continue living their life as normal, pursuing activities that align with their values even if they spark body image negativity [8]. The more flexibility an individual has the higher their quality of life will be since they are free to live according to their will, even in the face of image negativity. While some people have the skills necessary to regulate their negative thoughts and emotions healthily, many experience the inverse of body image flexibility, body image inflexibility. Body image inflexibility is the inability or unwillingness to experience negative appearance-related thoughts and emotions [9]. Those who have this inflexibility often avoid situations that could potentially trigger these thoughts and emotions because they are completely unwilling to entertain them. This inflexibility can dominate an individual’s life, causing them to drastically change their behaviour avoiding places, people, and situations they otherwise would not. Eating disorders are the most frequently investigated behavior and how it is affected by body image inflexibility. Together, Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia have produced some valuable findings in this area, with studies involving over 500 collegiate female participants [10,11]. The authors found that emotional eating and binge eating were moderated by body image flexibility [10,11]. In a separate instance, body image inflexibility was found to be significantly related to eating disorder symptoms and was moderated by BMI [12]. Conversely, Moore and associates found that body image inflexibility was predictive of eating disorders independent of BMI [13].Beyond eating disorders, body image inflexibility scores, as measured by the BI-AAQ, are predictive of and meditate an individual’s body dissatisfaction and comparison of their body image to those around them [14]. Although self-body evaluation and comparison to others may be extremely difficult to observe directly, body image inflexibility scores can help identify individuals that are waging these internal battles that may otherwise go undetected. Mancuso demonstrated this in a study where inflexibility scores fully mediated appearance evaluation and harmful coping strategies among females ranging 18-51 years old [9]. This means that individuals with higher inflexibility scores were more likely to engage in appearance fixing and avoid experiences that would put them in situations that would cause them to have those thoughts and emotions in the first place. There is hope for those experiencing psychological and emotional stress caused from body image inflexibility, as self-compassion has been shown to be a moderating factor. [15].Since body image inflexibility has been shown to affect behaviours in some female populations [10,11,12,13,14,16] it is imperative to investigate what behaviours it affects among collegiate female athletes. For a female athlete this could possibly look like skipping strength and conditioning sessions (SCS) out of fear that they will trigger thoughts and feelings of body negativity, or perhaps body comparison as shown by Fereira and associates [17]. Because collegiate female teams train together as a group in spaces with mirrors, SCS could potentially be a high-risk environment for body comparison.Although body image has garnered attention in some fields it remains an overlooked public health issue and warrants greater attention and understanding [16]. While it is well documented that [1] a high percentage of collegiate female athlete’s experience body image negativity and [2] females frequently suffer from body image inflexibility, there is a paucity of literature documenting body image inflexibility among female collegiate NCAA Division I (DI) athletes. Hence, the purpose of this study was to examine the link between body image inflexibility and female NCAA DI SCS habits. It was hypothesized that those exhibiting greater image inflexibility would positively correlate with having skipped a SCS as well as wanting to skip a SCS.

| Figure 1. BYU Women’s Soccer Team celebrating success (Image courtesy of BYU photo) |

| Figure 2. Strength and conditioning sessions are a key component of competitive success (Image courtesy of A. Staheli) |

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

- The participants for the study were current D1 female athletes from several universities. Participation in this survey study was completely voluntary and the consent form was built into the beginning of the survey. The Southern Utah University IRB committee approved the study and consent document (IRB Approval: #30-012023a).

2.2. Procedures and Instruments

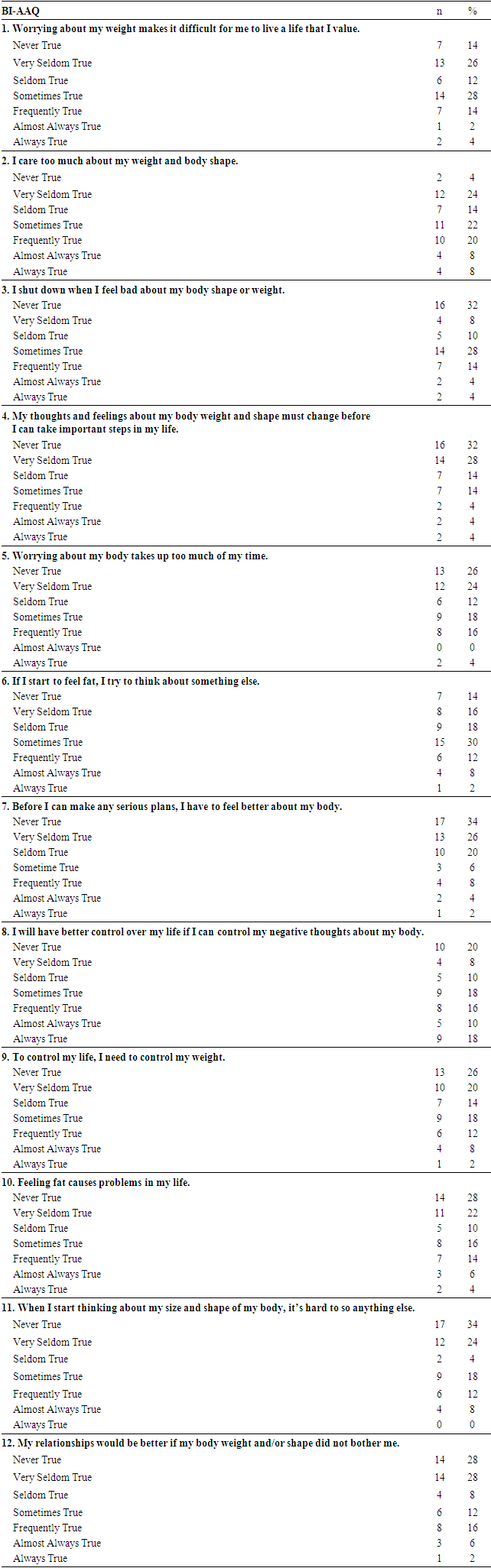

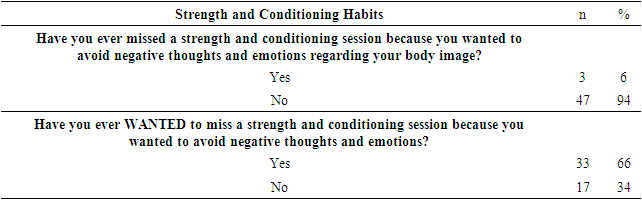

- Participants were recruited by connecting with the assistant athletic directors and coaches of different universities. Institutions that were willing to participate were then given a QR code that interested athletes could scan. The QR code then took them to the survey where they could sign the consent form and take the survey in a comfortable environment of their choosing.The survey measured body image inflexibility via the Body Image-Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (BI-AAQ) [18]. The BI-AAQ consists of 12 items measured on a 7-point Likert scale. All questions in the questionnaire are negatively worded, for example, “worrying about my weight makes it difficult for me to live a life that I value.” The Likert scale spans from 1 (never true) to 7 (always true), thus a higher number represents stronger inflexibility. Along with the BI-AAQ, the survey included two additional yes/no questions: (1) Have you ever missed a SCS because you wanted to avoid negative thoughts and emotions regarding your body image?, (2) Have you ever WANTED to miss a SCS because you wanted to avoid negative thoughts and emotions?.

2.3. Analysis

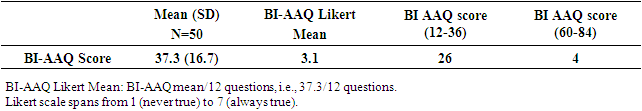

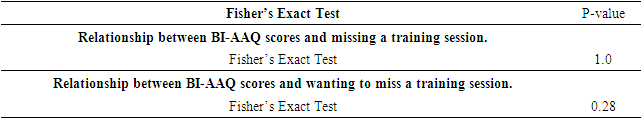

- The mean and SD of the participant BI-AAQ scores were calculated. The BI-AAQ scores were then stratified into those scoring in the binary ranges of 12-36 or 60-84. The 12-36 range indicated that on average the participant scored a question as never to seldom true (i.e. 1-3). The 60-84 range indicated that on average the participant scored a question as frequently to always true (i.e. 5-7). A Fishers Exact test (α≤0.05) was then used to compare the counts within the aforementioned binary BI-AAQ scoring ranges with the binary (yes/no responses) regarding SCS attendance and attendance willingness. Data management and statistical analysis were carried out in MS Excel.

3. Results

- Over a consecutive 8-week period, 50 athletes, all current female D1 athletes, volunteered and completed the survey. Tables 1-4 provide the responses regarding: the specific BI-AAQ questions, a broader overview of BI-AAQ scoring results, SCS training habits, and how body image inflexibility scores correlate with SCS habits.

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The purpose of this study was to investigate, among D1 female athletes, the relationship between an individual’s body image inflexibility scores and (1) whether they had missed SCS in their careers because of body concerns and (2) whether they had desires to miss a SCS due to those same concerns. This study evaluated levels of body image inflexibility [17,18] via the BI-AAQ, an instrument used in numerous studies over the last decade demonstrating body image inflexibility scores and behaviors they moderate. Among these studies it was found that body image inflexibility moderated eating behaviors [10,11], appearance evaluation and harmful coping strategies [19], and was predictive of an individual comparing their body to others [20]. As such, it was hypothesized that higher scores of image inflexibility would positively correlate with having skipped SCS and wanting to skip SCS.The relationships between BI-AAQ and SCS habits are shown in Table 4. There was no significant (or meaningful) relationship between BI-AAQ scores and missed SCS (p=1.00). The same conclusion was reached about the relationship between BI-AAQ scores and wanting to miss a SCS (p=0.28). As such, the research hypothesis was not supported.Table 1 presents several statistics that provide a small window of insight into the lives that many D1 female athletes live. While there are twelve questions in the survey, only select results that stand out will be discussed in the paragraphs to follow. The first question reflected that 48%, almost half, of the respondents either sometimes, frequently, almost always, or always felt that worrying about their weight makes it difficult for them to live a life that they can value. This is extremely important because living a life of value appears protective in nature towards mitigating depression and suicidal thoughts [21].The results of question 2 from Table 1 indicated that 58% of respondents sometimes, frequently, almost always, or always feel like they care too much about their weight and body shape. The results of question 3 indicated that 50% of the participants shut down when they feel bad about their body shape or weight. The results of question 4 demonstrated that 74% of respondents seldomly, very seldomly, or never felt that their thoughts and feelings about their body weight and shape had to change before they could take important steps in their lives. This result is interesting as it demonstrates that respondents generally felt they were able to move forward with large and important things in life regardless of how they felt about their bodyweight or shape. It would be interesting to further investigate why so many felt they could take these important steps in life noting that 50% indicated their inability to not “shut down.” In the same vein, the results of question 7 indicated that 80% of respondents seldomly, very seldomly, or never felt like they had to feel better about their body before they could make any serious plans. Another point worth noting comes from the results of question 8, where 62% of the participants (sometimes, frequently, almost always, or always) felt that they would have better control of their lives if they could control their negative thoughts about their bodies. These aforementioned results may be salient for sport performance professionals and administrators because it suggests that teaching the skills necessary for managing negative thoughts about body image may lead female athletes to feel more empowered pursuing their life ambitions.Table 2 presents a more general overview of the BI-AAQ results. The mean score over the 12 questions was 37.3 with a standard deviation of 16.7. In order to normalize the BI-AAQ total score of the twelve questions, the average Likert score across all 12 question was calculated and found to be 3.1, answered as “seldom true.” The average score of “seldom true” across the 12 questions would suggest low body image inflexibility among the participants. Table 2 also shows that 26 participants scored between 12-36 and 4 participants scored in the range of 60-84. The SCS habits as influenced by body image inflexibility are shown in Table 3. Of the respondents, 94% had never missed a SCS because they had wanted to avoid negative thoughts and emotions regarding their body image. While the vast majority had never missed a session, 66% of respondents reported that they had at one point, or another wanted to miss a SCS session so they could avoid those same thoughts and emotions. Or worded another way, while only 6% of female D1 athletes missed a SCS because they wanted to avoid negative thoughts and emotions regarding their body image, 66% had WANTED to miss a SCS because of the same concerns. This demonstrates what many intuitively perceive, that SCS attendance does not mean wholehearted engagement on the athlete’s end as they may be preoccupied with negative thoughts and emotions regarding their body image. Likewise, being preoccupied in a SCS environment may lend itself to lack of concentration while executing various resistance training modalities and predispose the athlete to an injury.Based on the results of this study, neither BI-AAQ scores nor attendance are indicative of an athlete’s desire to attend a SCS due to body image concerns. As such, sport performance professionals need to find an effective (and non-triggering) manner whereby athletes can express their negative thoughts and emotions regarding their body image.There were several limitations worth mentioning regarding this study. There were 50 respondents all from one state in the United States and were not selected randomly. As such, potentially compromising the external validity of the study conclusions [22]. Further, we assumed the BI-AAQ scores were a valid assessment of the NCAA female DI athlete’s body image inflexibility. Likewise, we assumed the athletes recalled accurately and responded honestly regarding their SCS habits, noting that we did not stratify the results based on year in sport (i.e. freshman-senior). Also, it is possible that athletes with body image inflexibility simply avoided participation in the study, a scenario that could potentially trigger negative appearance-related thoughts and emotions. We also did not separate the results based on sport type, specifically aesthetic vs. non-aesthetic sport [23]. Aesthetic sports (gymnastics, diving, and cheerleading) require competition apparel exposing much of their body [23,24]. We suspect those athletes competing in aesthetic sports may have very different concerns regarding body image flexibility. Finally, the investigators in this study were all male (i.e. he/him/his) and we are well aware that we may have a large blind spot regarding the interpretation of the results of the current study. As such, we view the results of the current study as a starting point for coaches and athletes to discuss within the context of their unique team and sport.Going forward, further research should focus on how to help D1 female athletes who worry about their weight (and/or body image) to the point that it makes it difficult for them to live a life that they value. Answering questions such as: what is the best way to discover which athletes are struggling with body image inflexibility, or what are possible interventions that help them foster a life they value, would be of great importance. Helping athletes create a life that they value should be a high priority for individuals in charge of leading student athletes.

5. Conclusions

- While 66% of the D1 female collegiate athletes in this study have wanted to miss a SCS to avoid negative thoughts and emotions regarding their body image, there was no meaningful relationships between BI-AAQ scores and missing a SCS or wanting to miss a SCS. However, coaches should be vigilant regarding the quality of participation of an athlete in a SCS session that the athlete wanted to miss.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML