-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2022; 12(4): 81-88

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20221204.01

Received: Dec. 10, 2022; Accepted: Dec. 25, 2022; Published: Dec. 30, 2022

Bottom-up Perspective of Leadership in Sports: Examining the Requirements of Athletes on Their Trainers’ Competences

Ramesberger Reinhold

Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, SI, Slovenia

Correspondence to: Ramesberger Reinhold, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, SI, Slovenia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The purpose of this study is to examine the bottom-up perspective of athletes in competitive sports concerning their competence requirements on their trainers. Competitive athletes (N = 138) from the regional team level up to the national team level (in individual and team sports) rated within a questionnaire their own requirements, wishes and perceptions on their trainers behaviours and competences. The gathered data is analysed using SPSS 28 and AMOS 28. The results revealed that there are moderate correlations between certain leadership competences and the followers’ engagement. They indicated that the “Knowing-Being-Doing” of trainers is relevant for their acceptance by the athletes. „Being“ revealed to be the most decisive factor. Furthermore, the trainers’ visions revealed to be a perceived lack by the followers. As a conclusion the leader-centred top-down approaches are not that suitable and, furthermore, the holistic personality of the trainer is decisive for his acceptance. The findings highlight practical implications for competence development of sports trainers.

Keywords: Leadership, Competences, Engagement, Athlete, Trainer

Cite this paper: Ramesberger Reinhold, Bottom-up Perspective of Leadership in Sports: Examining the Requirements of Athletes on Their Trainers’ Competences, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 12 No. 4, 2022, pp. 81-88. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20221204.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Leadership is a relevant ongoing topic in science and practice with a generally wide range of applications and contexts in many walks of life, one of which is competitive sports. There is an emerging consensus in the sports literature that the leadership which a trainer applies is important for outcomes in individual sports as well as for team sports. In soccer teams, for example, the leaders in the role of trainers are decisive for a team’s success and they are firstly replaced if the team has not been successful. Specifically in the field of competitive sports, the individual athlete’s success and in team sports the team success is the dominant criterion for (further) employment as a trainer. Trainers in competitive sports have a complex field of activity in which they are evaluated as constructors of their individual athletes’ success or their teams´ success. The great significance of leadership and, thus, the particular importance of competences in the profession field of sports is obvious, and many theories suggest that leadership is vital for effective sports performance. In this respect, the topic is filled with an enormous, vast number of leadership theories and styles. Most of these approaches consider leadership as a leader-centric topic [1,2,3]. Literature reveals an overwhelming amount of leadership research and an underdeveloped body of knowledge on followership knowledge [4,5,6,7,8]. Whereas follower research has gained in general moderate interest by some scientists categorising them into different types, such as Kelly´s typology (1988; 1992) [9,10], the typology of Chaleff (2009) [11] or the one of Barbara Kellerman (2012) [12], the followers’ perspective in sports towards their trainers has not been in the focus of quantitative research, yet. As mentioned above there is specifically in high performance sports a high level of dependency between the trainer and the athlete, and thus the leader-centred theories may appear outdated and not appropriate. While, in many profession fields, the display of obedience for formal reasons may work to a special extent, in sports it is an indispensable must for a trainer to gain the acceptance of the athletes, who are being led [13,14]. This acceptance is voluntary and based on what is perceived by the led athletes. For this reason the purpose of the present study was to turn the usual top-down approach upside down and give the followers, who are the led athletes, a voice to address their requirements towards their trainers. With this approach, a new quantitative research based piece of knowledge should be achieved that can be used in the development of suitable trainer competencies.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Idea

- With this research, it was the goal to detect through the lenses of followers, which requirements they have concerning their trainers’ competences especially in uncertain and unpredictable times. The in-depth investigation was guided by four hypotheses:Hypothesis one (H 1) postulates that followers claim a qualified (honest, transparent, individual informative) feedback to improve their motivation and as outcome their engagement. The claim is derived from practical experience, where unqualified general symbolic praise for matters of normality does not show any effect. Instead, it can even come across as ridiculous or offensive [15]. Feedback can also have negative effects on engagement by reducing the experience of autonomy and self-efficacy when it is uninformative [16,17]. On the other hand, many studies evaluated that the appropriate feedback and the appropriate use of feedback significantly and substantially impact improvements in task engagement [18,19]. Furthermore, genuine feedback from a leader (trainer) that is respected by the recipient (follower) can arise to an intrinsic reward [20]. In general, psychology provides a vast body of research about feedback [21,22]. The impact of feedback can either be positive or negative[23], but according to Fishbach and Finkelstein (2012) [21] there is no consensus on whether positive or negative feedback has more benefits and thus H1 approaches from the bottom-up perspective of the athletes to detect which kind of feedback they require and how this is correlated with their engagement.Hypothesis two (H 2) assumes that followers require a clear articulation from their trainers of what they expect, from whom, in which time, in which quality and for what greater long-term purpose (vision) and, as a result, thus they engage more actively. The Hypothesis is intended to approach the truth from followers’ (athletes’) perspective towards contracts. In general contracts are used to regulate a wide range of interactions, activities and relationships and thus they have an impact for curbing undesirable behaviours [24], and they can help to communicate clear expectations [25] and thus boost motivation. The theory of expectancy goes in a similar direction by stating that a contract providing a clear path to a desired goal can increase motivation to perform [26]. In contrast, referring to the Self-Determination Theory, contracts may minimize people’s freedom and then they display less interest [17,27,28] or even resist or sabo-tage the desired behaviour and hoped outcome according to the Psychological Reactance Theory of Brehm (1966) [29]. H2 thus examines whether a clear contract (in sports) induces positive or negative affects according to the athletes’ bottom-up point of view.Hypothesis three (H 3) postulates a positive correlation between the followers´ recognition by the trainer and the followers’ engagement. According to the humanistic psychology of Maslow, Perls and Carl Rogers, recognition and appreciation is an existential human need. The use of recognition/appreciation by a leader/trainer can be extremely motivating and lead to better performance [30,31]. According to the insights of Comelli and Rosenstiel (2003) [32] recognition for good work done, is a decisive factor for enhancing the engagement of followers. According research findings of Bartscher (2001) [33], followers show a minimized engagement if there is a non-appreciative leadership culture. In such a context they either do not have the chance to show their potential or they are no willing to do so [33]. In this respect, H 3 is intended to detect what is true by the bottom-up perspective of athletes.Hypothesis four (H 4) claims, that the consistent perception of a leader’s identity in “Knowing-Being-Doing” correlates positively with the followers’ acceptance. The components of leaders’ perceived identity by the followers are rooted in the three traditional domains of psychology, the cognitive (Knowing), the behavioural (Doing) and the affective/attitudinal (Being) component [34,35,36]. According to current research-findings the identity- that is how one sees oneself [37,38], has positive effects on motivation and engagement because people strive to embrace consistent positives identities and to avoid negative identities [39,40,41,42]. A positive identity, thus correlates with leader effectiveness [43] and motivates behaviour [44]. Under this aspect H 4 investigates if this holds also true for the followers acceptance of their leaders, when the followers’ perception of a consistent leader identity (how they enact their role), measured by indicators of the constructs knowing, being and doing reveals positive. H4 thus, turns the usual approach were the leaders are investigated who they think they are [45] upside down and examines the requirements of followers on their leaders’ in order to accept them [37,46]. Leader acceptance in turn is indispensable to exert a positive influence on the followers’ performance [13,47].

2.2. Participants

- A total of 138 German competitive athletes (78 male, 60 female) from regional team level up to national team level participated in the study. All participants were active competitors in either individual sports or in team sports. The sample consisted of competitors in cross-country skiing, biathlon, ski mountaineering, alpine skiing, snowboard, bobsleigh and athletics (track and field) of the upper mentioned leagues (levels). In team sport, the individuals (youth and adults) of soccer teams from regional level up to the German national soccer league were surveyed. The age span was 16 to 50 and the mean age of the sport competitors was 29.07 years (SD = 8.31). They had practiced sport as competitor (at different levels according to age classes) for an average of 15.4 years under the guidance of trainers (SD = 5.94).

2.3. Measures

- The survey was designed as a cross-sectional empirical quantitative Web-Survey using a standardized self-administered Online-Questionnaire [48] as measurement instrument. It was conducted in Germany as an ex poste facto research which examined samples of active competitors. There was no experimental treatment; instead of that the belonging to the group of competitors was the already existent treatment, thus it was a cross-sectional non-experimental design [49]. The questionnaire was created with the SoSci Survey online tool and the modalities of measurement were Self-Report Measures. The questionnaire consisted of 77 items, broken down into subsystems in order to provide the participants a rough structure.

2.4. Procedures

- A hyperlink to the survey questions was directed to the targeted respondents via their email address or their social media accounts in Facebook, Whats App and LinkedIn and in some cases via their trainers. The clink of the link enabled them to access and fill in the questionnaire [50]. The item format contained in the majority Rating-Scale-Questions with a 5-Point Likert scale [51,52]. The coding system of the items valued a high score going along with a high specification of the questioned characteristic. The followers were asked to rate each item strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree or strongly agree. Apart from that they had the provided extra column to rate “no opinion”. Additionally, there were some multiple choice questions with one item, were the participants had the possibility to add their own statement or individual remarks.

3. Statistical Analysis

- In order to address the study’s purpose, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS 28, thus validating the posited relations of the observed variables and the underlying constructs in the measurement model and the Structural Equation Models (SEM) for the hypothesis testing. For these assessments, the recommendations of Bentler (1990) [53], Hair et al. (2009; 2012) [54,55] and Meyers et al. (2005) [56] were used, which can be summarized by the following rules of thumb:Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) .90 equals an acceptable fitting model. CFI and TLI > .95 equals ideally values and thus a good model fit. CFI >.80 to .90 is sometimes permissible/reasonable [53]. A Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < .05 equals a good model fit. A RMSEA .05 - .08 is acceptable. According to Meyers et al. (2005) [56], RMSEA .05-.10 can be valued as moderate. RMSEA >.10 equals a bad model fit. A CMIN/DF < 3.0 is good and < 5.0 is acceptable. According to Hu and Bentler’s rule (1999) [57], two of three fit indices should meet the minimum cut-off values [58].

3.1. Measurement Models with Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

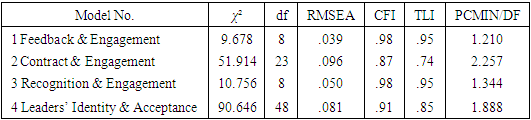

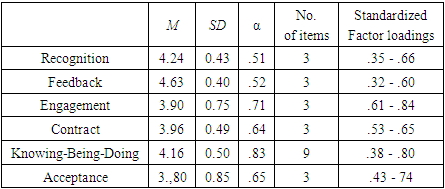

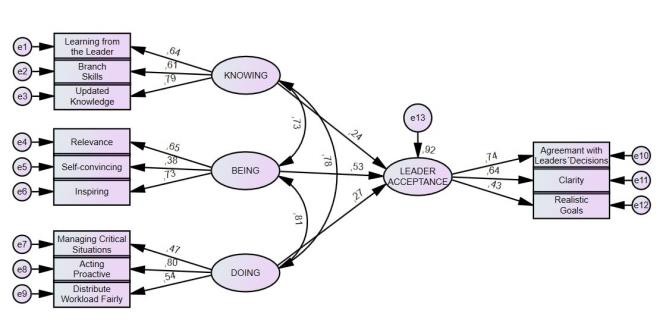

- A CFA was conducted using AMOS 28 in order to validate the posited relations of the observed variables and the underlying constructs in the measurement models. The relations were correlated between the trainers’ feedback and the athletes’ self-rated engagement, a clear articulated contract and the athletes’ engagement and the athletes’ recognition by the trainer and the athletes’ engagement. The perceived identity of the leader was measured by indicators to the constructs of „Knowing, Being and Doing” and this was correlated with the athletes’ acceptance. The fit of the models can be seen in Table 1, the models fit to the data and thus supported the approach of the hypotheses.

|

|

3.2. Hypothesis Test of H 1-3

- After the CFA, AMOS 28 was again employed to conduct the hypothesis tests through SEM. For data analysis, the same fit indices used for CFA (2 /df, RMSEA, TLI, and CFI) were utilized to assess the proposed model. As model, the Full Structural Model was used, which assesses the relationships between the constructs but also includes the measurement indicators and errors. The standardized regression path coefficients and the proportions explained variance are illustrated in Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Factor loadings and standardized coefficients in the SEM for testing hypotheses H 1-3 |

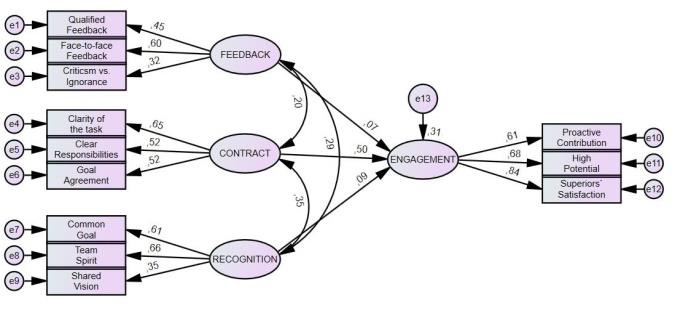

3.3. Hypothesis Test of H 4

- H 4 was also tested with the use of an SEM. The standardized regression path coefficients and the proportion explained variance are illustrated in Figure 2.

| Figure 2. Factor loadings and standardized coefficients testing H4 |

3.4. Additional Finding

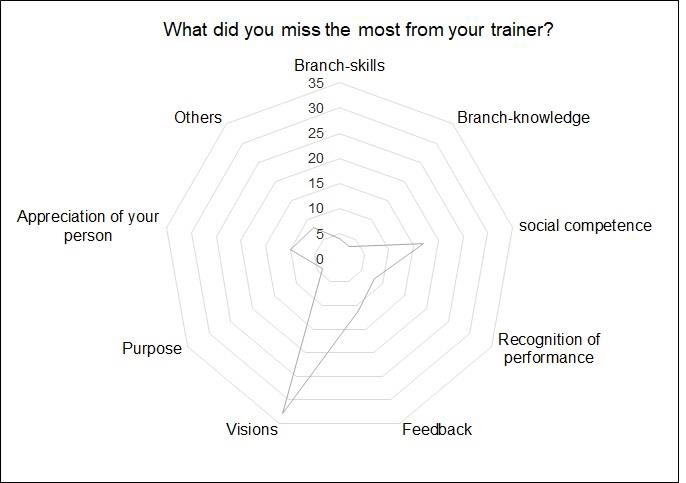

- Considering the frequencies within the different items, it was obviously that the lack of visions was complained about the most (cp. Fig. 3).

| Figure 3. Most noted frequency of complaint |

4. Interpretation and Discussion

- The aim of this article was to examine the athletes’ requirements on their trainers and the impact of them on the athletes’ engagement and the leaders’ acceptance by the athletes. The analysis shows empirical evidence that there is a moderate positive link between the leaders’ competences in providing feedback, contract and recognition and the followers’ engagement. According to the data, the variance of engagement is explained to 31% by the variables feedback, contract and recognition. This moderate correlation may be explained by the fact that in competitive sport are persons active who show per se a high engagement which is based on their intrinsically motivation. Nevertheless, the study demonstrates that a suitable feedback, contract and recognition is beneficial for the followers’ engagement. Athletes require an honest individual informative feedback instead of general symbolic praise and they prefer justified critics over ignorance. This goes along with findings from Hattie and Timperlay (2007) [23] confirming that feedback is effective in case it contains a high information level. This means in turn, a trainer needs the competence to communicate face-to-face with his athlete(s) also when there is something negative to say.The research reveals that, from athletes point to view, a clear contract has positive effects on their engagement. This may be explained by reducing uncertainty and providing a clear goal setting in expectation, time and quality level. This finding corresponds with the findings from Hirsh, Mar and Peterson (2010) [59] saying that a contract reduces anxiety and thus as follow-up uncertainty. Additionally a clear con- tract gives orientation on the long-term way to a high level performer (top-athlete).Recognition and feedback by the trainer show surprisingly very low regression weights (.09 and .07) in correlation with engagement of the athletes. This can be interpreted in the direction that the objective result (ranking list) of a competition shows very clear the performance level and thus it substitutes to a special extent the recognition and feedback from the trainer. The official result in a competition is already the recognition in the form of an automatically performance feedback [60]. Furthermore, this low correlation confirms the findings of McInerny and McInerny (2002) [61] stating that self-regulated persons with a channelled motivation towards achieving attainable and achievable goals need less feedback [61].From the analysis it is evident, that there is a strong link between the perceived identity (knowing, being, doing) and acceptance. The acceptance of a trainer by his athletes is explained by the variables knowing, being and doing to 92% with the highest regression weight on “Being” (.53). In conclusion it is evident that the led perspective of the athletes evaluate the perceptions of the holistic personality of their trainers. To be fully accepted as a trainer it seems not sufficient to have updated trainer-knowledge and apply it into trainings when playing the trainer role, more than that it is more about the “being” of the trainers which is spotted in their behaviour, attitude, remarks, lifestyle etc. and thus in their self. Obviously it makes a difference for athletes if trainers play only the role of a trainer or if they are trainers by their identity given by themselves but also given by the followers. Especially in times of social Medias trainers must be made aware that their “being” can be spotted in all situations.Furthermore it was empirically shown, that athletes require a trainer able to show and share visions for their sport career. This shed light on the fact that visions in the sense of long-term goals for an individual athlete or a team are in sport indispensable as athletes have to accept in most cases a period of more than 10 years of intensive training out of the comfort zone. In the sample, the average of training years was 15 years, which underlines the importance of the visions (long-term goal setting) given by the trainer(s) in order to provide the achievable „what for“ of the training over a series of years. The visions must be adapted to the athletes’ age and their development level, they must be challenging but must also be achievable and most of all they must be shared with the affected athlete(s). In these terms, it can be recommended to specify a vision in:- An outcome (result) goal/vision which includes the impact of the athlete and as well the rivals.- A performance goal/vision e.g. reaching a distinct running time at a special development level (age-class), which is only dependant on the athlete.- An action goal/vision which shows the way how to achieve result and performance goals within a current situation (sport action) but also along the long-term timeline (Athletes’ development).Limitations:As with any research, the current study is subject to some limitations, which need to be addressed. First, the present study consisted of German competitive athletes in individual sports mainly in winter sports and in team sports in soccer. Thus it is not proven if the results of this study may also hold true to other sport disciplines, therefore the generalizability is limited. Second, no distinction was scrutinized between the different levels of athletes. For details of differences between regional or national league athletes and differences between individual and team sports further research is needed. Third, the quantitative data, which show the “explored reality” at a time, are interpreted some-how qualitative and it must be respected that trainers as well as led athletes are human beings and especially athletes are no „average-people“. Fourth, the survey was conducted during the fragile and uncertain context of the COVID Pandemic and the “Russian-Ukraine-war” and thus the wish for visions in the sense of orientation may be higher than in “normal times”.

5. Conclusions

- Although some limitations existed in this study some conclusions can be drawn in the light of the above shown findings:The holistic trainer identity, is evaluated by the athletes through the perceivable „knowing, being and doing“ of their trainers. A consistent identity concerning all three factors is crucial to achieve a high level of acceptance. Being is empirically proven the significant factor. There is moderate objective measurable positive correlation between the trainer competence in providing a clear contract and the athletes´ engagement. So it can be derived that athletes want to have a clarity what is expected and realistic achievable by them. The clearer the contract for a clear and realistic goal the clearer the engagement to achieve the set goal(s). The recognition and feedback to the athletes` performance by the trainer is substituted to a special extent by the objective results on a ranking list and the intrinsically motivation of athletes, thus this has a minor influence (not significant) on the athletes’ engagement, but nevertheless feedback is required to be honest, informative and face-to-face. Visions in the sense of long term goal setting and orientation along the long-term timeline of the targeted sport career of the athletes are expressly required by them.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML