-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2022; 12(3): 61-72

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20221203.02

Received: Aug. 11, 2022; Accepted: Sep. 5, 2022; Published: Sep. 15, 2022

Organizational Dialogic Communication and Engagement: Examining the Relationship Between Dialogic Strategies and Facets of User Engagement in Nonprofit Sport Organizations

Mehdi Rezzag-Hebla1, Farah Rahal2

1Department of International Affairs MarkeTic Laboratory, EHEC Alger, Kolea, Algeria

2Department of International Affairs, EHEC Alger, Kolea, Algeria

Correspondence to: Mehdi Rezzag-Hebla, Department of International Affairs MarkeTic Laboratory, EHEC Alger, Kolea, Algeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Previous studies of organizational online communication through the dialogic communication framework suggest that adhering to the dialogic communication principles could result in greater public engagement in virtual spaces. By way of content analysis, this study examined the contribution of dialogic strategies to foster various aspects of user engagement, i.e., user-generated content, user response, follower network extensiveness, and network growth. This study offers the first attempt to examine nonprofit sports organizations in the light of the dialogic communication literature as applied to both the website and social media, i.e., Facebook. Theoretical and practical implications were also discussed.

Keywords: Public relations, Social media, Organizational website, Engagement, Dialogic communication

Cite this paper: Mehdi Rezzag-Hebla, Farah Rahal, Organizational Dialogic Communication and Engagement: Examining the Relationship Between Dialogic Strategies and Facets of User Engagement in Nonprofit Sport Organizations, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 12 No. 3, 2022, pp. 61-72. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20221203.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

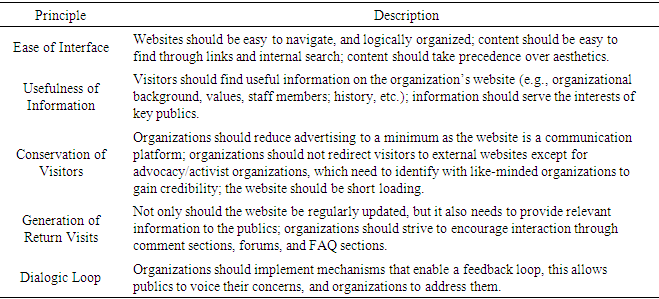

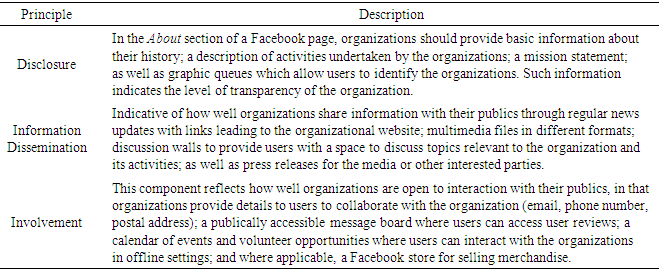

- With the advent of Web 2.0, research in organizational communication has promoted the use of online media outlets (websites and social media) as a vehicle to enable two-way communication and relationship building. Building relationships with online users begets favorable results such as trust, brand loyalty and positive brand image [1]. Dialogic communication theory with external publics has served as a blueprint for organizations that endeavor to build mutually beneficial relationships with their publics [2], [3] especially after the emergence of social media (SM). In their initial study, Kent and Taylor's [2] argued that the web was being used as an extension of traditional media in that the organizational website assumed the role of an information broadcasting platform. As a result, Kent and Taylor's [2] proposed a framework for organizational relationship building using websites, which has set the path for numerous studies on online relationship building strategies. The authors argue that dialogue should be at the nexus of the organization-public relationships. This framework comprises five principles (a) ease of interface, (b) usefulness of information, (c) conservation of visitors, (d) generation of return visits, and (e) dialogic loop (see table 1 for a summary of the dialogic principles). During the two decades following the emergence of the SM phenomenon, researchers have applied the framework to various platforms to assess organizations' or public figures' relationship-building strategies in different contexts (table 2 for the principles’ adaptation to Facebook , [4]; see also [5], Youtube; {Citation}Wang & Yang, 2020, Twitter).

|

|

1.1. Literature Review

- 1.1.1. Review of the dialogic principles: originally, the dialogic framework was proposed as a blueprint to guide practitioners toward a better use of the web to generate dialogue between organizations and their constituents as well as a tool to assess organizations' relationship-building strategies [2]. Using the dialogic communication theory, the dialogic principles build upon two-way symmetrical communication with organizations and their constituency as parties in a dialogue. At the time, dialogue was considered the outcome that organizations should strive to achieve, this view would later shift toward user engagement. Kent and Taylor [2] argued that websites (and subsequently SM) provide the venue on which interactivity takes place to reach, ethically and transparently, a mutual interest.1.1.2. Research using dialogic principles on Websites: subsequent to Kent and Taylor’s [2] proposal of the dialogic principles and their first operationalization as a framework to measure dialogue in activist organization’s web-mediated communication [9], wherein the authors have identified a predominance of one-way communication in addressing key publics through the website. In their study, Taylor et al. [9] argued that staff members assigned to manage the website were usually well-versed in the technical aspects but lacked adequate communication training to address the public and recognize the importance of two-way communication. Many studies have followed suit by applying the framework to measure dialogic readiness in organizational and public figures' websites from various sectors. Early studies applied the dialogic communication framework to examine the use of the organizational website in the case of for-profit, nonprofit, advocacy groups, and public figures. [10] examined university website use, their study revealed that liberal arts institutions tend to operationalize the dialogic features of the website more than their doctoral counterparts, Gordon and Berhow [10] also identified a positive correlation between user retention and the degree to which the dialogic principles are implemented. In the case of public figures, Taylor and Kent [11] examined the use of congressional offices' websites as a conduit for relationship building with their constituency, results revealed a subdued use of the dialogic features as the websites were used primarily for information dissemination. Similarly, Ingenhoff and Koelling’s [12] examination of Swiss charity fundraising organizations' websites revealed low employment of the dialogic features even if these organizations realize the importance of engaging in a conversation with the publics. Conversely, Park and Reber’s [13] examination of Fortune 500 corporations' relationship-building strategies revealed a high reliance on dialogic communication to foster public trust, satisfaction, and intimacy. The contrast between nonprofits and for-profit organizations in their use of the web to build relationships with the publics, as illustrated in the previous examples, seems to be consistent even on SM platforms.1.1.3. Research using dialogic principles on social media: with practitioners’ adoption of other forms of communication on the web, i.e., social media, researchers also adapted the dialogic communication framework to accommodate several SM platforms, e.g., Sweetser and Lariscy's [14] content analysis of US House and Senate candidates use of Facebook, the authors found individuals who wrote on candidate walls consider themselves on friendly terms with the candidates, while candidates rarely, if ever, respond to these messages. Sweetser and Lariscy's [14] concluded that although the mere use of Facebook is a dialogic feature, public figures are not using Facebook for two-way symmetrical relationship building; Bortree and Seltzer's [15] research on outcomes of dialogic communication on Facebook by environmental advocacy groups in which the authors argued that using dialogic strategies to create opportunities for dialogic engagement may produce positive outcomes such as increasing the number of individuals who interact with the organization in terms of network activity on the organizational profile as well as network extensiveness in terms of its follower base; Ngai et al.'s [16] comparison between Chinese and German corporations in the way cultural factors influence their communication on Chinese SM, Weibo; findings indicate that SM users gratify different communication styles depending on the company’s origin, i.e., users favored individualistic communication style for German companies and a collectivistic style in Chinese companies’ messages. As regards the applications of the dialogic communication framework in sport, Watkins [17] examined the influence of dialogic strategies on the likelihood of fans engaging with their favorite US professional athletes by employing Parasocial Interaction Theory [18] which addresses consumers’ mediated interactions with personas that is, an illusionary experience, such that consumers interact with personas1, and by measuring the overall attitude of fans towards the athlete on Twitter. Watkins [17] found that the usefulness of information can have a significant effect on engagement and enhancing attitudes towards a public figure despite the lack of two-way communication. In a similar study, Watkins and Lewis [19] found that professional athletes’ utilization of platform features on Twitter (i.e., hashtags, and multimedia content sharing) contributes significantly to the conservation of visitors. Apart from these two studies, however, no literature implementing the dialogic communication framework in the case of sport could be found; that is not to say that no other research was conducted to investigate sports organizations' online communication, e.g., Winand et al. [20] provided a case study of Fédération Internationale de Football Association’s (FIFA) use of Twitter to communicate with football fans regarding its activities; their findings suggest that FIFA uses Twitter in an asymmetrical one-way fashion. There are however two drawbacks to this study –Though the study addressed sports organizations' online communication on a global level, it only examined one organization, which limits the generalizability of the findings; second, the study focused on organization-fans communication, thus omitting other stakeholders.Across the majority of studies that have implemented the dialogic framework, there seems to be a recurring pattern, that is researchers’ convergence toward the consensus on the subdued use of the dialogic components (e.g., [4], [8], [21]–[23]). Ensuing from this consensus, Taylor and Kent [24]–[26], the same authors who conceptualized the framework, commented upon researchers for failing to distinguish between the process and rules, and actual dialogue and its outcomes. Criticism regarding the emphasis on the process suggests that the employment, or nonfulfillment, of certain features on the website or SM platforms, is the equivalent of demonstrating that dialogue has, or has not, taken place. In their study of the top 100 US nonprofits' use of Twitter, Lovejoy and Saxton [27] found that most organizations use Twitter for informational purposes relative to the other two components, and considering that prior studies have implied that, in relying on information dissemination, organizations have not been “living up to their interactive, dialogue potential”, Lovejoy and Saxton [27, p. 349] argued that dialogue is not the pinnacle of organizational communication; rather, it is one essential piece of the “communication puzzle”, the authors argued that even fully developed organizations will continue to share informational messages in a one-way fashion. The main objective for organizations should be to motivate stakeholders to take action (e.g., donations, signing petitions for nonprofits; making a purchase for for-profit organizations). 1.1.4. Engagement: within the literature on the organization-stakeholders relationship, the concept of engagement has been often used in conjunction with notions such as listening, openness, and dialogue [28]. Such notions have led to theoretical outcomes like cooperation, making meaning, mutual understanding, adjustment, and adaptation performed by parties of a relationship [29]–[31]. Taylor and Kent [26] situated the concept of engagement within dialogue, in that they conceptualized engagement as a procedure and an orientation leading to ethical relationships that safeguard the interests of both parties by finding common ground. From a practical perspective, engagement can be viewed as how online users relate to and interact with the organization's representation on the web, be that its official website or its SM profiles [32]. Through this lens, engagement is considered one of the non-economic benefits of the organization's presence on the web [33]. SM sites and even websites can be equipped with analytics tools to measure the levels of engagement based on the different types of follower interaction, e.g., shares, comments, retweets, etc. [34]–[36]. Such interactions are considered manifestations of the phenomenon called engagement [37], [38], and the use of metrics provided by analytics tools allows practitioners to quantify it and carry out benchmarks across different platforms. In this subsection, we have attempted to provide an overview of engagement both from a theoretical and a practical perspective. However, in the present research, we elect Lovejoy and Saxton’s [27] scheme that they called the "hierarchy of engagement", which is a process that takes place over three stages: information; community building; and action. Lovejoy and Saxton [27, p. 350] argued that "Information is the core activity to attract followers, Community-focused messages serve to bind and engage a following of users, and Action-oriented messages serve to mobilize the resource, i.e., the community, that has been developed through informational and community building communication". Lovejoy and Saxton [27] offered a definition that transcends the theoretical boundary and purposefully guides practitioners toward better use of their online assets, which ultimately facilitates meeting organizational objectives by fostering public effort. In the present research however, the authors only account for the first two stages of engagement – i.e., outcomes of information, and outcomes of community building endeavors – for it is difficult to assess action-based engagement and would require a case study design.1.1.5. The impetus for the research: the literature review suggests that although researchers have investigated organizational communication and relationship-building strategies through the dialogic communication framework, little research operationalizing the framework has been conducted to examine sports organizations. The sports industry is a standalone component in the modern world with ties to cultural, and economical elements of the social fabric. As such it requires more scholarly attention. Furthermore, the few studies of sport communication available through the dialogic communication lens have two drawbacks, that is they only focused on professional athletes, and individuals. No research was conducted to examine organizational communication within the framework. The second drawback applies to most available scholarly research on the subject, in that researchers have examined organizations within specific national boundaries with the USA and China as the most prominent ones, this limits the generalizability of their findings. Finally, researchers have been focusing on either organizational websites or SM, but no research has examined online dialogic communication with an inclusive approach that combines SM with the website. We argue that SM and the organizational website should be viewed as part of a continuum that comprises the communication apparatus available to organizations.

2. Methodology

2.1. Sample and Data Collection

- As regards our choice of the sample, i.e., National Olympic Committees, evidently, these are nonprofit sport organizations, which further emphasizes the importance of online media to circumvent the lack of resources required to leverage traditional media like television and print. Additionally, NOCs have ties to the international sports arena, e.g., the International Olympic Committee, regional sports associations, as well as continental and international sports federations. It, therefore, constitutes a framework of conformity within which NOCs operate despite their national environment. In other words, although each NOC operates within a single country with distinct cultural climate, examining a sample of NOCs should offset cultural idiosyncrasies, which in turn, contributes greatly to the generalizability of the findings, as contrasted with an examination of national sport organizations within a single country or region.This study operationalized the dialogic communication principles (Table 1; [2]) as well as the framework adaptation to Facebook (Table 2; [4]) as predictors of user engagement. To consolidate our data, first, we have manually collected URLs of National Olympic Committees' websites (N=206) from the publicly available list of NOCs recognized by the International Olympic Committee [39]. Following this step, the websites were manually visited to ensure their availability and that content hosted on these websites was updated within the last three months, this resulted in the removal of 32 NOCs. In a second phase, we collected Facebook URLs corresponding to our sample, the Facebook pages had to be verified or linked to on the website. By the end of the second phase, 44 NOCs were removed from the sample. Facebook was selected based on a prior examination where it was found to be the platform on which NOCs are most present. Additionally, the structure of Facebook is most favorable for establishing dialogue, in this regard, Kent and Lane [24, p. 5] argued in a comparison between Twitter and Facebook that Twitter is an unlikely place to hold a genuine conversation due to its public character, additionally, people come to Twitter sporadically; Facebook by contrast, is comprised of private networks of friends and acquaintances, thus has a higher potential for dialogue enabled by its relational nature and other features.Being part of a larger research project, we ensured that NOCs in our sample provided email contact information, this requirement was necessary for supplementary data collection. Following this phase, we obtained a sample of n=93 NOCs whose Facebook pages and websites were accessed approximately within a period of two weeks. Although, data obtained by way of email interviewing is not discussed in the present study, this filtration step has been stated to explain why the final sample comprises 93 NOCs instead of 130 NOCs.

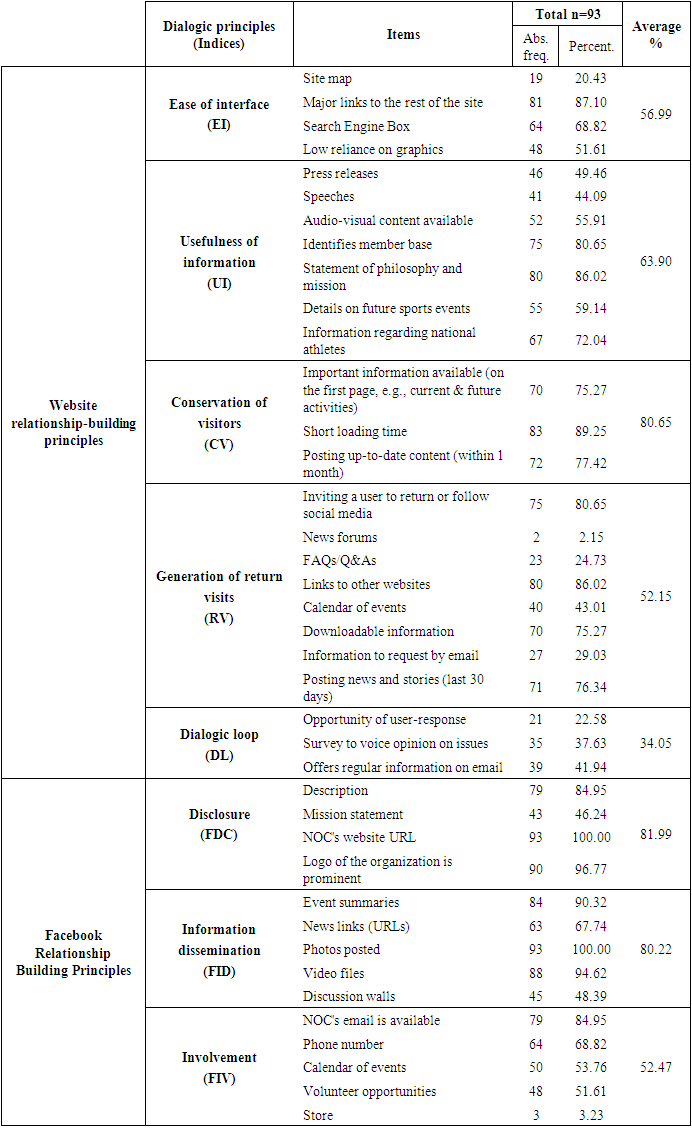

2.2. Content Analysis

- Our codebook comprises five principles for the website and three principles for Facebook (see, dialogic principles in Table 3). The website principles were constituted of twenty-five items; the Facebook principles were constituted of fourteen items (see, Table 3). Items for both platforms were dichotomously coded, 1 for the inclusion of the feature or 0 otherwise. The loading page speed was assessed using Google Developers’ toolkit [40] to circumvent potential disturbance in measurement stemming from the researchers’ internet network. Websites loading in under four seconds scored 1 on this item [41].

|

3. Results

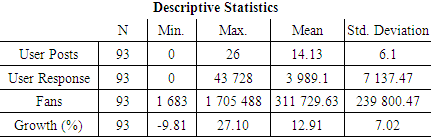

- To answer the research question, a series of multiple linear regression models were fitted to the data for each outcome variable. First, the dialogic principles for the website were used as predictor variables. Each multiple regression model was fitted to the data in an attempt to investigate whether dialogic principles on each platform could significantly predict an outcome of dialogic communication (see Tables 4, and 5).The separation between the website and Facebook was opted-for to identify the contribution of each platform toward reaching the outcomes of dialogic communication, the authors cannot offer the reader a framework of reference as this is the first instance of multiple linear regression model applied to the dialogic principles, previous studies relied primarily on mean comparisons through t-tests see [8], [19], [22].

3.1. Contribution of Website Dialogic Communication

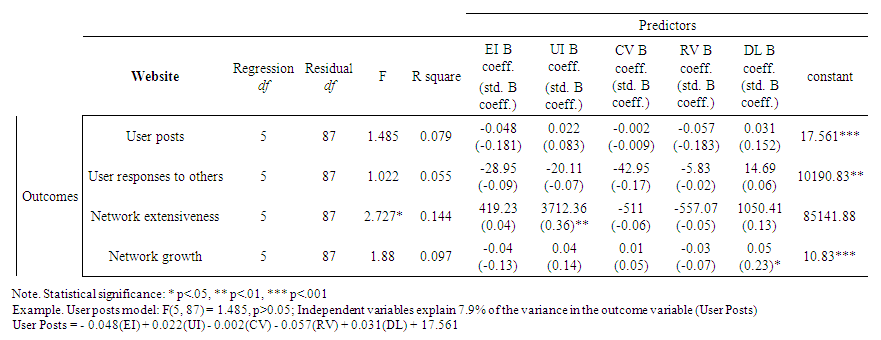

- Four multiple linear regression models were fitted to the data; only one model resulted in a statistically significant F statistic – F(5, 87)=2.727, p<.05, predictor variables accounted for 14.4% of the variance in the dependent variable, while only usefulness of information was found to be a statistically significant predictor (UI B=3712, p<.01), coefficients of the other four variables were statistically non-significant (Table 4).

| Table 4. Multiple linear regression models fitting website dialogic principles as predictors to outcomes of dialogic communication |

3.2. Contribution of Facebook Dialogic Communication

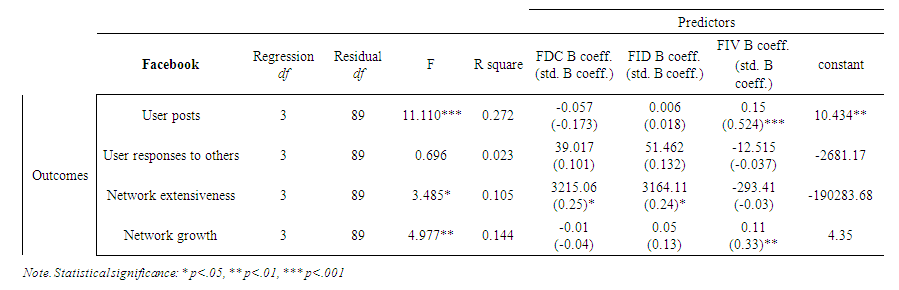

- Similarly, four multiple linear regression models were fitted to the data, using Facebook dialogic principles; three of these models yielded a statistically significant F statistic:User posts: F(3, 89)=11.110, p<.001, predictor variables accounted for 27.2% of the variance in the outcome variable. However, only involvement was found to be a statistically significant predictor (FIV B=.15, p<.001). The other two predictors were found to be statistically non-significant (Table 5).

| Table 5. Multiple linear regression models fitting Facebook dialogic principles as predictors to outcomes of dialogic communication |

4. Discussion

- The availability of sophisticated website functionalities, and SM platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Youtube, has offered national sport organizations the potential to establish reciprocal relationships and dialogic interactions with their online publics. Online channels help organizations to tap into the dialogic potential with little resources as compared to traditional media like television, radio, and print.To investigate whether national sports organizations are tapping into this potential we have examined how National Olympic Committees are using their website and Facebook page to engage with their publics. We sought to accomplish this task by analyzing the content of 93 websites and Facebook pages. We carried out our examination through the dialogic communication framework [2], in addition to collecting data pertaining to the outcomes of dialogic communication identified by Bortree and Seltzer [15].Data collected on the website suggests that NOCs seek to reduce visitor bounce rate by regularly updating the organizational website with information regarding NOCs' activities as well as optimizing their web pages to reduce loading time. Additionally, it appears that NOCs address a variety of stakeholder groups by providing information that is of interest to each of these groups, i.e., the media by sharing speeches and press releases, fans and athletes by sharing details on future sports events as well as blog posts regarding national athletes provided to fans, and the general public by maintaining a level of transparency regarding organizational governance. However, there was a subdued use of the website as a tool for community building and engagement, in that little interaction between the organization and online users was attainable for the websites lacked interactive spaces like forums and comment sections, this suggests that NOCs view their website as an informational tool, which is further supported by the low score of the dialogic loop principle and is congruent with previous studies cf. [50], [51]. Notwithstanding this finding, it appears that NOCs use their website to achieve the informational component of the organizational communication hierarchy (i.e., information-community-action) proposed by Lovejoy and Saxton [27].Indeed, our sample had average to high scores on the Facebook dialogic principles, in that NOCs seek to help users to identify the organization, and its mission. Similarly, NOCs utilize various functionalities of Facebook to disseminate information on a regular basis. However, only half of the investigated organizations implemented community building strategies, which is illustrated by the average score attributed to discussion walls availability, such practice would drive users to create their own private spaces where they can gather and discuss topics related to the organization, which can affect the organization negatively considering that NOCs are discarded from the conversation, thus lowering organizational control on brand image. Nonetheless, we argue that the typology of the organization and its mission should be taken into consideration, as activist/advocacy groups are more oriented toward the public to fulfill their goals, the same applies to for-profit organizations where organization-stakeholder interactions influence organizational performance [4]. This further extends Kent and Lane’s [24] perspective on negative spaces, i.e., situations where genuine dialogue is not possible or appropriate, e.g., community members being disrespectful toward each other, or unwilling to be open-minded. We argue that organizational typology is also an influencing factor in that some are more reliant on online publics in reaching their objectives (e.g., activist/advocacy organizations; political candidates), whereas other organizations are quite independent in that regard. However, this is not intended as a normative assertion that encourages a lack of dialogue, rather it is a suggestion that organizational idiosyncrasies should be accounted for when evaluating their online communication.Similarly, action-based functionalities on Facebook like a calendar of events and volunteer opportunities were used by half of our sample, these functionalities help facilitate interaction with those highly involved with the organization, who expect extensive information regarding organizational activities. In addition, practitioners should utilize their follower bases to find volunteers who support the organization rather than offering volunteering opportunities on job listing platforms where users are not necessarily supporters of the organization.Before discussing the relationship between dialogic strategies and their outcomes, it should be emphasized that the goal of our study is to identify and discuss statistically significant results; non-significant models, which are largely attributed to website-mediated communication, were excluded from the discussion due to data inaccessibility regarding user interactions thereon. Thus, a lack of statistically significant relationships does not imply the absence of a said relationship. We argue that the lack of findings in certain areas (Tables 4, 5) implies the need for further investigation on what leads to successful communication strategies through the website.In comparing NOCs’ communication strategies on the website to their communication on Facebook, it appears that NOCs rely on the website mainly for informative communication with little interaction, while Facebook is used for informative communication as well as community building, and action. Facebook pages are still, however, predominantly used for one-way communication. In this regard, authors like Lovejoy and Saxton [27] argued that informational communication will still be the base form of communication. Thus, it should be expected that one-way communication will always take precedence over community building, and call-to-action. This claim is further supported by our findings, in that NOCs’ network extensiveness (i.e., number of followers/fans) is partly affected by information sharing on the organizational website. Additionally, sharing these messages across SM platforms, combined with disclosing information regarding the organization and its mission, seems to contribute towards the same end which is to increase followership, and thus reach. Another interesting finding is that, as sports organizations endeavor to involve their online publics encourages them to continually renew the conversation through content creation and sharing in spaces provided by the organization, in this instance discussion walls. Indeed, SM inherently enables a flow of information to be two- or multi-way, whereby it is not necessarily initiated by the organization, it can also be initiated by the public toward users or the organization. Hence, organizations should involve online publics on SM platforms through interactive content including, but not limited to, a listing of upcoming events where publics can interact with the organization in real life; providing volunteering opportunities; and including these publics in the organizational decision-making process through surveys – the latter being dependent on organizational typology. Such practices beget an ongoing communication and interaction where organizations can hear their publics and react accordingly to reach a common understanding and co-create value [52]. In a study investigating SM use by for-profit sport organizations [53], practitioners highlighted a lack of control over content posted by users, especially when the message is negative, or factually wrong. Though providing a discussion space does not completely circumvent a lack of control over user-generated messages, providing discussion spaces for online users can help practitioners to monitor negative messages that can potentially harm the brand, thus allowing practitioners to respond promptly.Similarly, organizations that tend to involve their online publics seem to have more growth in their followership. Organizations that are open to user input have the potential to curb challenges inherent to the nonprofit status of organizations, such as limited reach, or a lack of financial resources to use traditional media for broader reach. It appears that involving online users goes beyond retaining an enthusiastic follower base, it helps organizations maintain a level of growth, thus providing organizations with outlets where it is possible to exchange information in real-time and to ensure that content echoes among massive audiences without temporal or middleman constraints [54]. Previous studies have identified a relationship between information sharing and a subsequent increase in followership [55], [56]; our results indicate a relationship between usefulness of information and the size of the follower base, our results also indicate that growth is affected by organizational openness to public involvement. Therefore, this study complements previous research by identifying an additional strategy that contributes toward network growth which is organizations' openness to public involvement. Across the majority of studies that have implemented the dialogic framework, there seems to be a recurring pattern, that is researchers’ convergence toward the consensus on the subdued use of the dialogic loop. Indeed, many researchers argue that practitioners use the web in a one-way fashion where their online platforms serve as information dissemination outlets [4], [8], [21]–[23]. As indicated earlier in this section, our results seem to tell a different story. Informational communication on the website as well as on SM appears to be an effective means toward community building, whereas NOCs endeavors to involve their online stakeholders seem to contribute significantly toward increasing user generated content. We recommend therefore, the reconsideration of the current narrative which regards informational communication as a shortcoming.In summary, this research provides valuable insight into the contribution of dialogic communication strategies to various aspects of user engagement in that informational communication and transparency were positively related to larger followership on SM, whereas organizations' openness to public involvement was significantly related to user-generated content and network growth. Though one-way communication was found to be the predominant form of communication employed by practitioners, it did not prevent national sport organizations from fostering public engagement, this further strengthens the argument that informational communication is in and of itself a fundamental component for generating engagement.As to practical recommendations, results indicate a subdued use of interactive features on the website and Facebook, practitioners are encouraged to consider employing their platforms more interactively, such as Facebook and Twitter polls, regularly updating their calendar of events, and providing a comment section on blogposts hosted on the website. Additionally, we encourage practitioners to provide discussion spaces for their online publics, having a discussion space prevents users from creating private spaces where organizations are excluded from the discussion, this brings users closer to the organizations and it enables a feedback loop with no middleman, thereby allowing the organization to react promptly were issues to arise, and thus more control over brand image and perception. However, we caution practitioners from content policing or censoring as it may have negative repercussions on the brand. Indeed, users are entitled to voice their own opinions, and practitioners should consider potential repercussions before intervening.As regards limitations and research recommendations, this study focused on nonprofit sport organizations, thus limiting the generalizability of our findings, and as we have seen in the literature review, studies employing the dialogic framework in sport have focused solely on public figures, hence, we recommend investigating for-profit sport organizations through the dialogic relationship-building framework to encompass the sports industry within the dialogic communication literature. Secondly, our regression models explained approximately 10-30% of the variance in various user engagement variables, this may be indicative of the existence of other factors which, potentially, have a higher influence on user engagement on web platforms. Future research on factors influencing user engagement is required to offer a wider picture of best practices regarding organizational communication. Finally, the findings regarding the contribution of the dialogic principles on the website are somewhat limited by the inaccessible website data, therefore, a note of caution is due when interpreting the outcomes of dialogic communication on the website.

5. Conclusions

- In any event, helping sport organizations realize the potential of dialogic communication on the web is of paramount importance for the research agenda. Sports organizations are increasingly trying to foster engagement and mobilize their stakeholders on different web platforms. Identifying the best practices, and understanding how to devise successful strategies are important, especially for nonprofit sport organizations. We hope that our study contributes toward this goal and that more researchers will set out to study the sports industry from within the scope of dialogic communication.

Appendix A. Engagement Variables’ Descriptive Statistics

|

Note

- 1. Mediated representations of presenters, celebrities, or characters (Labrecque, 2014, p. 135).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML