-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2022; 12(2): 23-33

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20221202.01

Received: Oct. 20, 2021; Accepted: Nov. 15, 2021; Published: Mar. 15, 2022

Empirical Examination of Perceptional Differences of Esports among American Students

Li Chen , Mark Still , Xianhua Luo , Kun Wang

Delaware State University, USA

Correspondence to: Li Chen , Delaware State University, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Research literature in electric games or sport has storage of empirical analyses of perception of esports. This study was designed to fill the void of identifying important factors affecting perceptions of the young generation toward esports, supply a validated measure for essential perceptions of esports, and examine perceptual differences across American students. Voluntary participants (N = 468) responded to the survey with the validated instrument and expressed Socialization as the most important factor of perception toward esports, followed by Technicity, Economics, Attraction, and Recognition. Findings indicated significant gender differences and variations in the playing status of esports among American students. The study provided empirical references for educators and administrators to enhance their understanding of esports and supplied quantitative findings in favor of esports being part of sporting activities.

Keywords: Esports, Factor Analyses, Gender Difference

Cite this paper: Li Chen , Mark Still , Xianhua Luo , Kun Wang , Empirical Examination of Perceptional Differences of Esports among American Students, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 12 No. 2, 2022, pp. 23-33. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20221202.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Esports (also known as electronic sports, e-sports, or eSports) is increasingly becoming a popularly social phenomenon and an area of interest for sport enterprises and educational institutions. The popularity of esports has shown a significant increase in extracurricular activities and economic growth of nearly $3 billion with predicted esports market to surpass $1.5 billion by year 2023 [20]. Such activity has received substantial media coverage through ESPN and Turner Sports [19]; and as an effective promotional platform for sponsors to reach their large pool of audiences [32]. Esports is considered as a sport played by the cyber-athletes online and shares many similarities in common with traditional sports [36]. The multimedia content supported by technology allows cyber athletes to enjoy the sport in a commercialized and passionate world (Asian Electronic Sports Federation [1]). According to National Association for Collegiate Esports, esports has is adopted into more than 80 collegiate athletic programs in the United States [31]. It becomes not only a major competition of professional esports players, but also the most popularly recreational or entertaining activities among casual gamers including adults, adolescents, and especially for children. Currently, there have been discussions or debates regarding the classification of Esports [e.g., 11,16,19,25]. With respect of what the scholars attempted to define esports and philosophical standpoint of ‘sport for all’ [1], researchers would continue to seek for determination of factors and perceptual expression of what esports should be. While their perceptual expressions were underlined theoretical bases in nature, more empirical findings need to be in place [8] to satisfy affiliated sentiments of esports. Hence, conducting a quantitative study of perception toward esports appears meaningful.

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Perception of Esports

- Perception, in general, refers to awareness of the environmental elements through physical sensation. In a social-psychological standpoint, perception is a sensory experience of the individuals toward certain objects or events and engages individuals’ awareness, experience, and response to the environmental stimuli differentiated from other psychologic terms such as affection or motivation [19]. As indicated by Stokes [43], perception is veridical under a natural condition and combines probabilistic sources of information in an optimal way to achieve an effectively deterministic outcome. Hoffman and his colleagues [19] presented that perception is a product of evolution intertwined with a broad consensus that emerge with reality. It also relates to observation, cognition and obtaining messages after the information is identified and processed. Other researchers contend that perception is a person's ability to experience and understand what happens in an environment that reflects expression and defined information [24]. Thus, perception of esports could be established through observation and cognitive experience from media messages.Researchers have attempted to classify esports based on their understanding and interpretation of existing literature. Martončik [30] perceived esports as a culture field with adopted rules, that allow individuals to voluntarily interact with each other, develop skills and achieve their life goals. According to Wagner [47], esports is “an area of sport activities in which people develop and train mental or physical abilities in the use of information and communication technologies” (p. 3). Hemphill [17] stated a view of esports in which it has “nature of sport realities, that is to electronically extended athletes in digitally represented sporting world” (p. 199). Esports is an area of activities that the participants develop their mental and physical abilities to communicate with technologies, and is an umbrella form used to describe organized and sanctioned competitions over internet [18,26,47,17]. A psychological elaboration of esports by Banyai, Griffiths, Kiraly, and Demetrovics [2] classified it as a sport because “it includes voluntary, intrinsically motivated, activities, and events are organized and governed by rules, includes a winner and loser, and concise skill” (p. 352). Esports has been considered as “the combination of electronic and sports which means using electronic devices as a platform for competitive activities” [1, p. 1]. This might be mostly agreeable among scholars [8,11,16,19,24] even if there has been inconsistency of precise perception in their polarized discussion [21]. Given the nature and characteristics of formational structure, popularity, and most of qualifications as a sport [16], esports seemed to be inclusive in the sport family of global communities [26].

2.2. Perceptual Deviation

- The perceptual deviation between favorable and reserved perceptions of esports has existed in current literature. The favorable opinions of perceive esports as a sport were interpretations from the social impacts, and therapeutic functions [21], rule-governed with contests of human skills [26], competitive characteristics through electronic interaction [49], and participation to improve physical and mental abilities, maintaining a social relationship, and obtaining competitive outcomes [14]. Also, the similarity of esports and traditional sports could be evidenced in phenomena of philosophy slogan, rewarding systems, national identity, education values, usage of media [22] along with required skills, popularity, and stability as well [44]. While sports could be any form of physicality with expected participation [16], the precise dexterity of esports players can be explored in their physical movement (fine motor skills) to manipulate objects [49]. Such perceptual supports ranged from physical activity with the necessary movement of virtual aviator to social and psychological needs of human, competition in nature, rules and governance, and social and media acceptance [14,30,44,49]. Although there is a connection between traditional sport and esports, there have been perceptual deviations that constrain esports. Such deviations include the perceived nature of Esports as cyber controlled games that have limited physical ability [34]; lacking govern bodies [15]; improvement in ranking systems [11]; legal concerns with trademark, patents, software development and ownership [25]; social and media acceptance [14]; as well as exclusion from the list of national sport participation [22]. Existing research findings indicate that perceptual deviation also occurs by social-demographic variables such as age, gender, education, and sport status. Teenagers were more attracted by electronic games than other age groups [36], and young people had a higher interest in both esports and traditional sports [25]. School-aged students were more likely to overplay games and showed addiction signs toward computer games than other social activities [30]. A healthy playing environment is recommended for esports participants to avoid misogyny and homophobic acts [29]. The social role of game developers must be monitored to restrict potential cyber harassment [6]. Other perceptual deviations include how esports players perceive values of visual authority; and monetary awards were more important than recreational gamers [33]. Previous studies indicated that esports is a male-dominated field with only a third of female participants [8], and women are less interested in esports compared to men [21]. Thus, gender inequality needs attention since gender equality is inclusive and mandated in traditional education institutions [11]. The perceptual difference of gender was reported in esports regarding self-perception and ability [10]. Women were found to be more emotional and better at dealing with emotions from themselves and others than men [10]. The study also showed that male and female participants scored equally for target emotions for both levels of stimulus intensity. However, the perception of non-target emotions was significantly higher than other dependent variables for men. Such difference might impact their self-perception and interpersonal empathy [10]. Moreover, gender difference of esports gamers was also found in analyzing acceptance of online games among participants. Male participants perceived playfulness, computer self-efficacy, and behavioral intention much higher than female participants while women experienced a significantly higher rate of computer anxiety than men [27,48]. Qian and colleagues [35] developed a scale to measure spectator motives of esports. With a focus of motivation of esports spectatorship, they found that skill appreciation and socialization of esports participants were similar to traditional sport consumers. In addition, Busch, Boudreau, and Consalvo [6] found that some electronic game contents and marketing discouraged female participants. Female gamers might be emboldened more than male gamers to perceive sexual comments as the environmental programs developed for the games. However, the finding remains unclear on how their overall perceptions of esports impact on their participation of electronic games. Further examination of gender difference would be synergic.

2.3. Factors Affecting Perception of Esports

- Current perceptions of esports and related theories provide a foundation for researchers to further scrutinize plausible domains of perception of esports. The possible domains could be synthesized and conceptualized as following factors including Attraction, Economics, Identity, Socialization, and Technicity.

2.3.1. Attraction

- According to Self-determination theory (SDT, [9]), attraction would be a plausible component in the extrinsic motivation that serves as an inner force to drive individuals to behave. Individuals are extrinsically attracted and motivated to act instrumentally with separable consequences or substantial outcomes. Satisfaction of psychological needs, interests, and economic reward would be good forms of extrinsic motivation [9]. The key attraction of esports is competition, interest, and enjoyment of activities that draw attention from individuals in societies at all levels, especially for young generations [36]. Curiosity and polymorphic characteristics of esports along with powerful electronic transmission have served as attractive elements [11,16]. Esports could be used as recreational, entertainment, competitive activities to provide people availabilities of escaping from work [30], entertaining with friends and peers [36], and competing for winning as well [2,4].

2.3.2. Economics

- Classic economic theory proposes that economics plays a major role in a capitalistic and free-market system in which individuals have opportunities to act in their self-interests [40]. Esports is impacted by financial and economic valuation and global commerce [11]. Esports is a lucrative and booming industry that has increased economic volume through organized competitions and media coverage [20] due to its passionate global fanbase [32]. The fluidly commercialized development of esports might be based on its effective process of competition and promotion [39]. Esports has contributed significant financial capital towards electronic arts, and economic activities are also evident in the development of sponsorship programs and partnership [20]; broadcasting and promotional spending [40]; increased awareness of licensed merchandise and software copyright [25]; and financial investment of entertainment spaces for competitive events [38].

2.3.3. Identity

- Perception of individuals toward certain objects could be explained as relationship between mind and body with contingent facts and ones’ brain states according to theory of identity [45]. This factor refers to collective perceptions relied on the facts and characteristics of the given sport with shared elements of traditional [14]. The ‘play’ is the origin of electronic games and serves as a critical motive that initiates fanbase participation, strengthens structure stability, mental and physical health, and facilitates socialization [44,46]. The element of ‘institutionalization’ reflects acceptance of media and governance, establishment of managerial structure, development of governing bodies and regulations, formalization of competition, and facilitating learning and coaching practice [24]. Esports requires minimal physical skill, movement of virtual avatar, and balancing of the body [16]. Placing physical and mental skill in a spectrum from highest to lowest, the higher physical skills a sport requires, the lower mental skills the sport needs for competition (e.g., boxing); in return, the higher mental skill a sport requires the lower physical skills is needed in a competition (e.g., shooting). Both skill sets need to be in place to classify an activity as a sport [15,25]. While skills and strategy of esports are necessary for individuals and teams to strive for a winning outcome [37], the equipment and facility are required to ensure functions of digital games [49].

2.3.4. Socialization

- Theory of socialization assumes that individuals need necessary skills and knowledge to function as a member of community and society that is a standard to a group process of living and life experience [29]. Esports serves as a social platform for members of society to participate, share interests and feelings, and function as a stress release relaxation, and leisure or recreation [12,22]. Esports could impact on both cognitive function of individuals and human relationship through social events (Olympics or world championships) and interaction among the participants and audiences [12,26]. Development of social media could have attuned to esports and manifold social and cultural effects of esports [26]. The nature of esports has also evolved social diversity based on its fanbase [11], and affected by social contexts and culture heritage [37]. Esports can be used to facilitate social functions and human interaction through its social event, and to strengthen media relationship by its management and participants [16].

2.3.5. Technicity

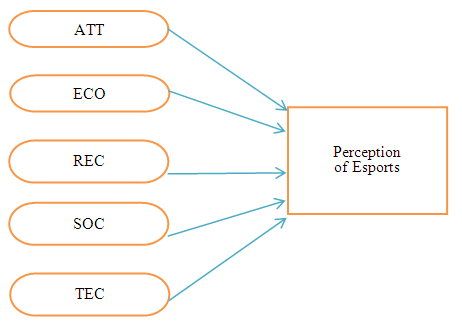

- Technicity refers to nature and quality to possess technical skills and technology by a specific group of people according to technicity theory [5]. Technicity is a unique factor of esports compared to other traditional sports [16]. It contains elements of the world wide web; online function of games; and broadband development that involves standardization, complex of technicity, and telecom engineering [36]. Technicity plays a critical role of supportive mechanism of gaming among the competitors [16]. While technical organs facilitate both psychic organs (bodily) and social organs (family or community) in esports, technicity supplies transforming power and connects physical organs and social organs [42]. Technical skills with human experience and behavior in digital games could strengthen operational effectiveness and ensure skillful play and positive mental outcomes [42,47]. Esports requires cyber athletes to be competent in hand-eye coordination, quick reaction, and skills to operate equipment supported by technicity [36]. Relying on the conceptual framework and proposed factors that could affect the perception of esports, a conceptual five-factor model is illustrated in Figure 1. Operational definitions of the factors can be found in the instrument section.

| Figure 1. Conceptual Model for Perception of Esports |

2.3.6. Purpose of Study

- Given the increased popularity of Esports, especially in the Millennial generation, the following research questions will be examined in this study. What perceptual factors of Esports are based on knowledge, experience, and observation? How would participants' perceptions be quantitatively and validly measured? What perceptual differences exist between Esports participants and participants from various backgrounds? Therefore, the purposes of this study are three-fold: (a) to identify important factors affecting perceptions of participants, (b) to supply a valid profile to measure perceived factors of Esports among the participants, and (c) to explore possible perceptual differences across the research sample.

3. Materials and Method

3.1. Participants and Instrument

- As majority of the esports participants and audiences were from young generation accordingly [22,28], the participants (N = 468) were selected from schools-aged students in eastern coast of America. Age groups were the students aged 19 and under (n = 130), 20 to 22 (n = 227), and 23 and upper (n = 171) including 239 female and 229 male students. Their education levels were categorized as the high school seniors (n = 130), 2-year college (n = 99), upper class of college (juniors and seniors, n = 145), and graduate or professional school (n = 94). There were esports players (gamers) who have had playing experience at least three years or more either at varsity teams of high school or college, or competing in the organized events or leagues of esports (n = 213), and non-players, who have either never played, or just played occasionally for lesser than three years, or only watched esports events (n = 255), respectively. A survey instrument entitled Profile of Esports Perception (PEP) was developed to collect quantitative data for the purposes of this study. The survey questionnaire contains a short introductive paragraph to inform the participants with the purpose, volunteerism, and confidentiality of study, followed by the self-reported demographic information sheet with PEP questions. The PEP includes five factors based on the operationally defined factors: (a) Attraction (item 1 - 4), it refers to perception of esports that stimulates or attracts interests or desires of students to participate in the play or audience; (b) Economics (item 5 - 8), it refers to the perception of economic impact or financial gains of esports through outcomes of promotion and competition of esports events; (c) Identity (item 9 - 14), it refers to the perception of organized esports competitions through cyber environment and contains recognizing general nature and characteristics of sports including playfulness, equipment, institutionalization and regulation, strategy and outcome, and required physical skills; (d) Socialization (item 15 – 19), it refers to the perception of development of social interaction, human relations, and communication by spectating or participating in esports for life experience, social activity, and culture heritage; and (e) Technicity (item 20 - 22), it refers to the perception of knowledge and skills of technical applications (software, devices, internet) for competently playing esports.

3.2. Procedure and Analyses

- At the first stage a pilot study was conducted to verify proposed perceptual contents and factors. In compliance with the guidelines of research ethics of American Psychology Association, the survey instrument, informed concern form to the participants, and procedure of testing were carefully reviewed and approved by the ethical human subject protection committee of institutional review board (IRB) before conducting the research. A total of 23 questions were generated through a wide review of literature and interview with some esports related individuals. All operational definitions of factors and associated items were evaluated by a panel of sport science faculty and athletic professionals (n = 5) with acceptable rate of 80% for establishment of content validity. A group of college students (n = 60) voluntarily participated in the pilot study. The data with the five factors were then analyzed by using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) of SPSS 20.0 [41] for reducing irrelevant items. The reason to use EFA first was that all drafted items were assumed to have little control of consistency between conceptually sound factors and item specifications statistically fitted to the expected factors although the content validity has established [13]. Principle Component Analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation was applied to explore correlation coefficients among the items and to identify the most parsimonious scale to preserve the measurement property of the pilot study. Delta value was set at zero and .50 criterion was used for factor loadings. A total of 22 items with factor loading higher than .50 were retained and only one item (it is not hard for new players to master skills of playing electric games) was dropped due to disqualified correlation coefficient of the item.The second stage was to collect data with a stratified random sampling designed for recruiting 600 voluntary participants. The sample pool contained 50 percent of the male and 50 percent of female students enrolled with full time status including 25% of regular students and 25% student-athletes in each of gender groups from high schools and universities in eastern coast of America. The researchers along with a group of trained graduate students administered the survey by hand delivering 600 survey packages to the sampled participants. The time spent to complete the demographic information sheet and survey questions of PEP ranged from 10 to 12 minutes. Of 600 packages prepared, there were 132 incomplete packages either unfilled due to their different class time or missed some information in the survey. A Total of 468 packages with 78% return rate were effective for data analyses.The third stage of study involved data analyses including that (a) EFA was used to reexamine consistency of item-factors with the final sample. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) with Structure Equation Modeling (SEM) of IBM SPSS Amos [23] were applied for specifying the indicators to the given latent variables [3,41]; (b) reliabilities were tested to determine the internal consistency and composite reliability within each of the factors for the final sample; and (c) Multivariate Analyses of Variance (MANOVAs) were used to test whether there would be possibly significant differences among each of the independent variables (age, education, playing status, and gender) across five perceptual factors. If significant differences would be found in MANOVAs, univariate F tests or Post hoc Scheffe tests would be followed to determine specific differences of the relevant groups on the specific factors [3].

4. Results

4.1. Factor Analyses and Instrument Validation

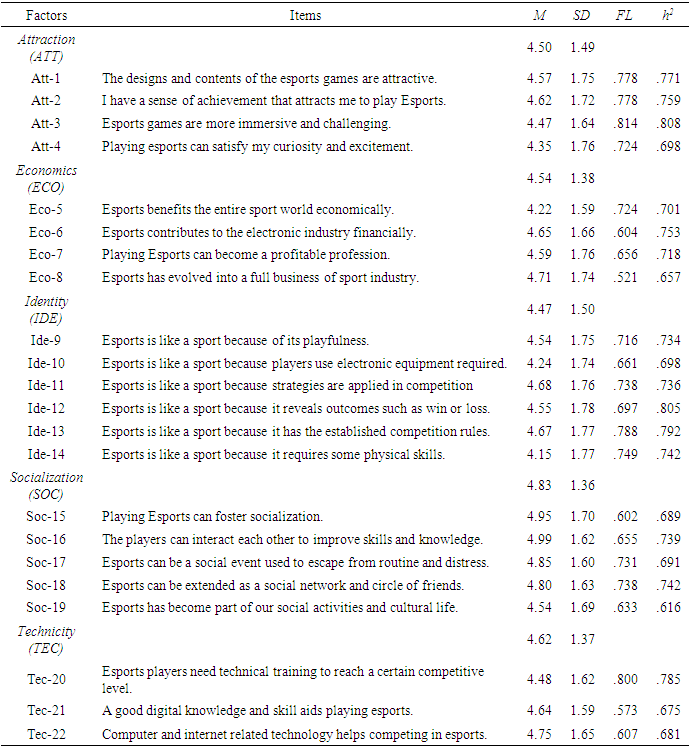

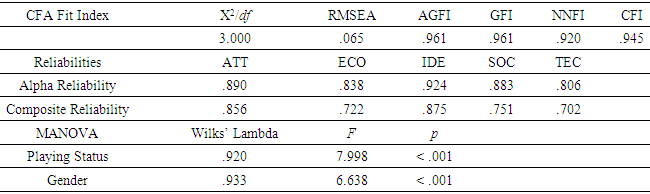

- Principle Component Analysis was applied to explore correlation coefficients among the items and to identify the most parsimonious scale to preserve the measurement property with the final sample (N = 468). Direct Oblimin rotation of EFA was performed based on the nature of oblique rotation [41] for the data. The 22 items were examined with satisfactory factor loadings (FL) ranging from .521 (item-8) to .814 (item-4). The values of community (h2) for 22 items ranged from .675 to .808 meeting the acceptable criterion [13]. Each of the extracted factors (latent variables) was highly corrected with expected constructs underlying the a priori conceptual framework. The means, standard deviations, values of h2 and FL of items are presented in Table 1.

|

|

4.2. Determining Mean Differences

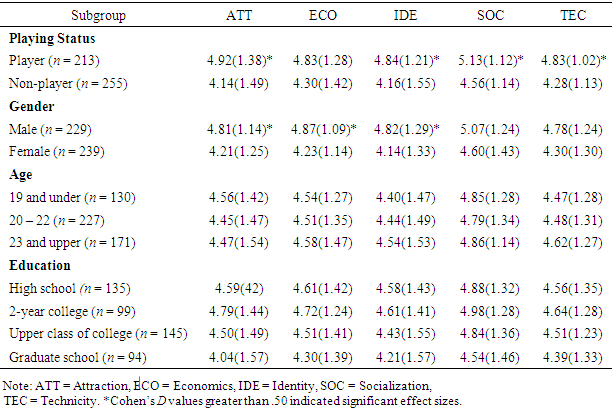

- The mean scores and standard deviations of five factors and 22 items are presented in Table 1. The mean scores and standard deviations for each of the subgroups are shown in Table 3.

|

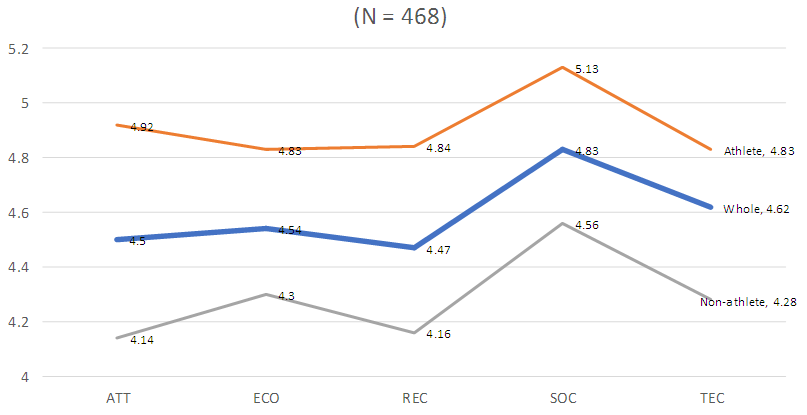

| Figure 2. Rated Means of Overall and Playing Status Differences Across Five Factors of Perception |

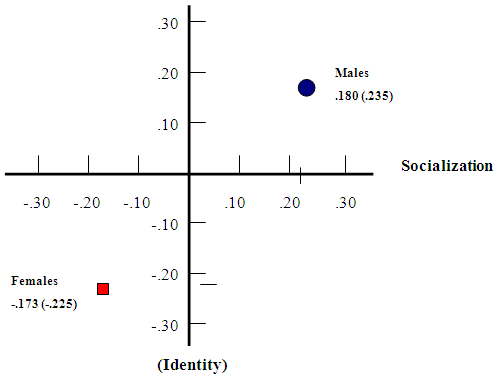

| Figure 3. Gender Differences Described in Deviations of Discriminant Scores |

5. Discussion

- The results indicated that some scored factor means were slightly over the midpoints of scales of the PEP among the participants. The finding indicates a fundamental preference among respondents who favorited esports sharing many characters with traditional sports, that is in line with existing literature [8,11,14,18]. It is interesting to note that Socialization was scored the highest and Identity was scored the lowest across the factors among the participants (see Figure 2). Perhaps Socialization is a commonly applied factor in many psychometric measures across motivation, perception, value, satisfaction in socio-economic studies of sport and physical activities. The result could be a plausible indicator to determine whether esports would be classified as a sport since all sports share social functions in common over other factors. The study demonstrated high social-psychological needs of individuals because all sports have provided an ideal social platform for people to communicate and socialize [29]. Like traditional sports, esports has evolved in diverse social groups and enhanced social interaction through its inclusive game culture [39]. As a remarkable indicator, esports has been highly valued for its social and competitive events such as esports tournaments and sponsored games [1,12,30]. Factor of Identity, however, was perceived as the lowest among perception factors. This may reflect divergent perceptions of participants from different social-demographics and playing status that affect consideration of whether esports could be inclusive in sport family. Noted the lowest rated item -14 (esports is like a sport because it requires physical skills) in the factor (M = 4.15), this item might have distorted the rating curve. The reason is that physical skill is the most disputable element of esports to determine if the activity is exclusive or inclusive as a sport [14,34]. Although esports competition relies on electronic devices and software, it involves physical activity or bodily movement through small skeletal muscles (fine motor) with required energy expenditure [49]. As argued by Hallmann and Giel [14] and Parry [34], however, it might be weak on typical physical ability and skill even though esports players do demonstrate their minimal physical skill and movement in practice and competition. The ratings reflected degree of their perception based on their feeling, attitude, motivation, and participative experience of electronic games as many respondents of this study disclosed themselves as esports players with certain number of playing years. The finding is identical with expressions of previous researchers who shared their reservation of esports with weak physical component, governing authorities, and acceptance of media and society that need improvement [14,25,43].Interestingly, there was no perceptual difference found in the age and education groups. The results opposed common expectation and research findings reported by Park and Lee [33], who found age differences only in perceptual values of esports. A possible reason may be that the age from 17 to 35 represents the young generation with education levels from high school to college. They may have had similar influences from the society, and they have grown up in information age with observation and experience of computer and internet proficiency as the Generation X and Y (born after 1977 to beginning of 21st century). Many participants have educated in America institutions and grown up in western culture and society, they have been familiar with cyber games that share many similarities with traditional sports. However, it may be inconsistent with study of Garcia and Murillo [26] who reported younger people (age below 18) would be more interested in esports than older groups. This could be deviated from either specific countries or sampled populations and further comparison is needed. The finding of this study may not contradict some previous studies which showed similarities of perceptions toward all sports including esports internationally [27,28,33,39]. Conceivably the perception of participants was mainly impacted by their experience of participating in esports and comprehensive characteristics regardless of age and education levels. Such references could be found in other studies [48,50] in which different perceptions and acceptances of esports existed only in gender groups but not in a relationship with variables of age and education levels among the participants. Moreover, the esports players perceived higher than the nonplayers on all perceptual factors but Economics. Possibly the esports players might have more experience of the electronic playing in organized practice and games compared to non-players. Their self-confidence and improved game skills might affect their perception of favorable identity. Bosc et al. (2013) denoted those who put more time in their skill training or game practice have stronger confidence for their goals of winning in cyber games. They could be more encouraged by increased sponsors and investors of esports as well [38]. In comparison, nonplayers may only play recreational video games at home or just watch the competitions online or television. They were uncertain to weigh characteristics and identify their positions on perceptual items on the rating scale. Hebbel-Seeger [15] and Ho [18] attributed this phenomenon to their ambivalence of virtual sport that may have similarities with traditional sports. The esports players and non-players rated similarly on economics. It is perhaps that both groups perceiving the economic impact of esports is based on their observation of esports and traditional sports in their popularity, media coverage, investment, sponsorship, and commercial activities [21]. This finding was realistic for psychological connection to cognitive perception [40]. The longer participants played esports, the more stimuli they would receive to influence their perceptions. Such preferences would come from their stronger interest, frequent involvement, and enjoyable experience. The result is supported by the study of Hebbel-Seeger [15] who indicated that professional gamers considering esports as a sport was based on nature of esports, players’ operational skills, agility to use equipment, quick reflexes, and strategical thinking in practice. The finding is also similar to the research of Xu [50] who stated that esports players may have more opportunities to engage in the culture, sponsorship, advertising tournaments, and other business engagement. Their direct observation may lead them to perceive esports as a sport although the game is in a cyber context [50].In addition, gender differences in perception toward esports were also found in this study. Male participants rated higher on the factors such as attraction, economics, and identity than their female counterparts. It is reasonable to assume that men might be more attracted by electronic games than their female peers. Accordingly, their primary interest might be more in machine or computer related operations [10]. The male participants rated economic factor more critical that might be attributed to their spending behavior and concern in purchasing related devices for playing online games individually or participating esports competition collectively. Their higher rating on Identity could relate to their more computer related skills and experience. Possibly male participants engaged more frequently in electronic games based on their favor or addiction of the games, willingness of expenditure, and awareness of identity for esports as a sport compared to female participants [22,24]. The male participants rated such perceptual factors higher than the female peers in this study that is consistent with a previous study of Cunningham and colleagues [8]. They indicated that nearly two third of male players and audiences were in esports. Funk and colleagues [11] called attention of Title IX of Higher Educational Act for gender inequality of esports that is the same as the traditional sports offered in educational institutions of America. Wang and Wang [48] also indicated that male participants were preferable more than male peers to factors of behavioral intention, playfulness, and computer self-efficacy than female participants who perceived computer anxiety higher than their male counterparts. In the studies of Fischer and his colleagues [10] and Busch and associates [6], gender difference was also reported in self-perception of the participants. Both studies explored that the female participants had a negative perception toward electronic games due to sexual contents and language programmed in some software and gaming environment. Such phenomenon should warn game developers and esports management to pay social and legal attention in software design and game production.

6. Conclusions

- The results of this study have provided empirical evidence for respondence to initial research attempts and met the purposes of this study: (a) the essential items and important factors affecting the perception of participants toward esports, were examined underlying plausible conceptual framework and empirical input; (b) the Profile of Esports Perception (PEP) specific for esports was validated for quantitative data collection to measure essential factors perceived by the participants; and (c) significantly perceptual differences were explored among the groups of playing status and gender of participants. Es ports could be embraced change, its influence would be continued to officially join the sports community [8,11,16,21]. All contemporarily competitive sports have experienced such improvement through their evolution by continuously building and strengthening the qualifications of sport. A research attempt to apply inductive application of theories with deductive support of empirical inputs has been exercised in this study. The results supplied quantitative data with the underlined the theoretical basis and filled a void of empirical research in perception of esports. Findings serve as references for the management of esports to make improvement and reconstruct their strategic plan as needed. Results may also encourage esports governing bodies with a further determination that esports has a theoretical foundation with empirical evidence to qualify it as a sport.While this study could contribute a penny of the quantitative findings to the esports related literature, its caveats might be considered for further research endeavors. For instance, the sampled population might be narrowed to the specific age groups for content verification and factor determination. Another improvement could be made on the enlarging sample size across the nation to ensure better generalizability of results. Moreover, while the 5-factor structure of PEP was acceptable as a psychometric measure with its statistical support, the model fit indices of PEP showed a slightly weakness on NNFI (.92) for perfection of hypothesized model [13]. Further study may be designed to measure and compare different populations internationally such as subsamples from the participants of European, African, and Asian countries since the esports was either originated from or has been valued highly over there in addition to America. It would be meaningful to administer a meta-study by synthesizing key points of all related findings of esports across academic disciplines to scrutinize both positive and negative attitudes for enriching research literature. Also, qualitative research including interview of esports players or game developers and conducting case studies of specific esports teams need to be in research agenda to find more informative opinions from the practitioners. Additionally, participant or spectator motivation of esports among school-aged students could be tested by using existing inventories or developing a specific scale to detect what their motives would be; or which incentive could be more influential to their behavior and participative decision of esports. It would be suggestive that governing bodies of esports should consider more physical movement components to be inserted in the game to strengthen the ‘sport’ nature, combined with physical ability and technicity. An example is that the players may be required to stand playing at a high computer desk, or physically to move their positions to operate devices between the stations by given distance and time. Researchers in the direction of esports should provide more guidance for the school educators and supply advanced research findings to assist management in convincing the society to truly embrace it in educational institutions and the global sports family.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML