-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2020; 10(5): 99-104

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20201005.01

Received: Aug. 23, 2020; Accepted: Sep. 10, 2020; Published: Sep. 26, 2020

Prevalence of Psychological Markers of Overtraining Amongst Elite Male Field Hockey and Soccer Players in Top National Leagues in Kenya

Ndambiri K. Richard, Andanje Mwisukha, Mugalla Bulinda

Department of Physical Education, Exercise and Sport Science, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Ndambiri K. Richard, Department of Physical Education, Exercise and Sport Science, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The purpose of this study was to assess the prevalence of psychological markers of overtraining amongst elite male field hockey and soccer players in top national leagues in Kenya. The study was limited to selected mood states of anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, tension and vigour that are applicable when assessing the mood states of athletes in exercise settings. The target population for the study comprised elite male hockey and soccer players in top national leagues in Kenya. A total of 232 participants (116 hockey players and 116 soccer players) were included in the study resulting into response rate of 71.6%. The research adopted the standard version of the Profile of Mood State questionnaire (POMS). T-test was used to determine whether there was any significant difference between the mood state profiles of hockey and soccer players at a significance level of P≤ 0.05. Results indicated that the two groups (elite male hockey and soccer players) differed significantly as far as mood state profiles were concerned. In conclusion, the study revealed that psychological markers of overtraining were prevalent among elite male hockey and soccer players. The study therefore recommended that there is need for coaches and other stakeholders to assess their players’ mood states during the playing season.

Keywords: Overtraining, Mood States, Elite Male Field Hockey and Soccer Players

Cite this paper: Ndambiri K. Richard, Andanje Mwisukha, Mugalla Bulinda, Prevalence of Psychological Markers of Overtraining Amongst Elite Male Field Hockey and Soccer Players in Top National Leagues in Kenya, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 10 No. 5, 2020, pp. 99-104. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20201005.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- To achieve maximal sports performance, athletes must be optimally trained. Successful training should incorporate high training volumes and adequate recovery [2,15]. At any rate, many athletes have a tendency of incorporating high levels of physical training and limited recovery periods into their training programmes, a situation that predisposes them to overtraining. General consensus in research supports the notion that overtraining is characterised by psychological disturbances [13,6]. Consequently, studies in exercise and sports psychology have focused on identifying the psychological markers associated with overtraining as possible indicators of overtraining [24,25,7].A wide range of psychological variables associated with overtraining, have been extensively investigated as possible markers of overtraining [12]. This study was limited to selected psychological markers that are used when measuring the prevailing mood states of athletes in an exercise setting. Specifically, the study assessed mood states of anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, tension and vigour. Research in sports and exercise psychology has demonstrated that the aforementioned mood states are useful in detecting mood fluctuations in exercise and sport settings [24,25]. The use of selected psychological states is clearly effective in predicting behaviour in sport settings [19]. Furthermore, research has documented strong associations between the above psychological markers as assessed by Profile of Mood States (POMS) and overtraining [18,15]. These mood states (anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, tension and vigour) adopted by the present study have been used to identify over-trained athletes [23].The reason why mood states associated with overtraining have been used as markers of overtraining is perhaps due to their ability to change in relation to the training load [11,1,20]. That is, as overtraining progresses to a greater level, the deterioration of positive mood (vigour) and the increase of negative moods (anger, confusion, depression, fatigue and tension) are clearly shown by the Profile of Mood States [10,18,16,22,3]. Similarly, optimal training is associated with increased vigour, coupled with reduced anger, confusion, depression, tension and fatigue. Thus, the mood state responses of athletes exhibit a dose-response relationship with the training volume in all subscales of the POMS [11,20]. This characteristic of mood states to change in relation to the training volume has made it possible to successfully identify over-trained athletes [1,20]. The current study therefore, sought to determine the changes of mood states between the beginning of the league associated with low intensity training, and peak of the league (many matches) that are accompanied by heavy and prolonged training. The comparison of the athletes’ mood changes between these two periods will help establish whether psychological markers of overtraining are prevalent among elite male hockey and soccer in top national leagues in Kenya. The advantage of this model where psychological responses are compared between periods of high and low intensity is that athletes are studied in their natural environment without manipulating their normal training regimen [17].Hockey and soccer at top national league in Kenya is highly competitive requiring repeated maximum performance over several matches over a season of approximately six to eight months. In addition to playing intensely during each game, the players undergo strenuous training before the start of the season, train for many days during the season except on a match days; and may also represent the national and international teams. Players’ performances may deteriorate without outwardly obvious reasons. Research has identified ‘overtraining’ as a possible cause for such drop in performances, especially among top level athletes and players. Despite the situation not being unique to Kenya, there is a dire need for establishing the prevalence of psychological markers of overtraining amongst elite male field hockey and soccer players in top national leagues in order to help in identification of athletes who may be over-trained. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess the prevalence of psychological markers of overtraining amongst elite male field hockey and soccer players in top national leagues in Kenya. The specific psychological markers of overtraining that were assessed included mood state of anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, tension and vigour. It was hypothesized that there is no significant difference in the mood state profiles between elite male hockey and soccer players in Kenyan top national leagues. The paucity of recorded empirical evidence in this area in Kenya demands the establishment of the prevalence of psychological markers of overtraining on elite male hockey and soccer players so that coaches would be able to identify overtrained athletes or those showing tendencies towards it. Thus, there is knowledge gap on possible ways of helping identification of athletes who may be overtrained. Hence, a greater need to establish the existence of psychological markers associated with overtraining after which there will be monitoring of athletes by coaches during training thereby offering a potential method for preventing overtraining.

2. Methodology

- Following right procedures, National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI), which acts as the highest authority for research authorization in Kenya, granted approval to conduct the study. The study targeted all elite male field hockey players participating in men’s hockey premier league in Kenya and all elite male soccer teams participating in Kenya premier league (KPL). The two sports disciplines were selected for this study because besides being team sports, they are also similar in terms of players composition (11 players in each team) during competition, positional designation (defenders, mid-fielders, attackers and goalkeepers) and starting status (starters and non-starters/substitutes). Additionally, both leagues have athletes playing at elite levels. Research studies evaluating psychological differences should use elite athletes as there is a possibility that athletes at this level have similar physical attributes [4]. These similarities made comparisons possible between these two sports based on the objective of the study. In both categories (hockey and soccer), a total of 324 (100%) participants (162 (50%) hockey players and 162 (50%) soccer players) were sampled through stratified random sampling at the beginning of the league. However, out of these, 232 participants (116 hockey players and 116 soccer players) were included in the study resulting into response rate of 71.6%. A demographic questionnaire that sought the demographic variable of type of sport (hockey and soccer) and the standard version of the Profile of Mood States (McNair, Lorr and Droppleman (1971, 1981, and 1992) were used for data collection. The Profile of Mood States (POMS) contains a total of 65 adjectives and statements that yield measures of anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, tension, vigour, and total mood disturbance (TMD). The scores for the six subscales in the Profile of Mood States (POMS) are calculated by adding the numerical ratings for items that contribute to each sub-scale. Each adjective in the POMS questionnaire is awarded the following scores: 0 (not at all), 1 (a little), 2 (moderately), 3 (quite a lot), and 4 (extremely) except ‘Efficient’ in the confusion subscale and ‘Relaxed’ in the tension sub-scale in which, the scores are reverse prior to being summed with the other items: 4 (not at all), 3 (a little), 2 (moderately), 1 (quite a lot), and 0 (extremely). The total score for ‘anger’ is determined by adding the scores for angry, peeved, grouchy, spiteful, annoyed, resentful, bitter, ready to fight, rebellious, deceived, furious, and bad tempered. The total score for ‘confusion’ is determined by adding the scores of the numerical ratings of the adjectives that constitute the feelings for confusion; unable to concentrate, muddled, bewildered, efficient, forgetful, and uncertain about things. For ‘depression’, the total score is determined by adding the scores for unhappy, sorry for things done, sad, blue, hopeless, unworthy, discouraged, lonely, miserable, gloomy, desperate, helpless, worthless, terrified, and guilty. For ‘fatigue’, the total score is determined by adding the scores for worn out, listless, fatigued, exhausted, sluggish, weary, and bushed. For ‘tension’, the total score is determined by adding the scores for tense, shaky, on edge, panicky, relaxed, uneasy, restless, nervous, and anxious. For ‘vigour’, the total score is determined by adding the scores for lively, active, energetic, cheerful, alert, full of pep, carefree, and vigorous. Finally for ‘TMD’, the total score is calculated by adding the scores for anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, and tension and then subtracting the scores for vigour. The following adjectives in the POMS questionnaire were used as dummy items and were not used for scoring; friendly, clear-headed, considerate, sympathetic, helpful, good natured, and trusting. A constant (such as 100) can be added to TMD formula in order to eliminate negative scores. The POMS questionnaire was administered at the beginning of the league (pre-test) in the month of February and at midseason (re-test) during the month of August to determine participants’ mood state changes that may have arisen from the training provided during the period under study. The current study adopted Cronbach alpha approach to establishing reliability. Alpha was calculated for each subscale at both tests (pre-test and re-test). According to the statistically acceptable criterion values 0.70 to 0.95 [21], the reliability analysis Cronbach Alpha scores at pre-test established high reliability for the subscale of anger (α = .77), depression (α = .82), fatigue (α = .82) and tension (α = .75). Confusion (α = .58) and vigour (α = .65) subscales indicated moderate reliability. The reliability analysis Cronbach Alpha scores at re-test established high reliability for the subscale of anger (α = .79), depression (α = .86), fatigue (α = .83), tension (α = .70) and vigour (α = .73). Only the subscale of confusion (α = .61) indicated moderate reliability. T-test was used to determine whether there was any significant difference between the mood state profiles of hockey and soccer players. The acceptance or rejection of the hypothesis was set at a significance level of P ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Mood States of Elite Male Hockey Players

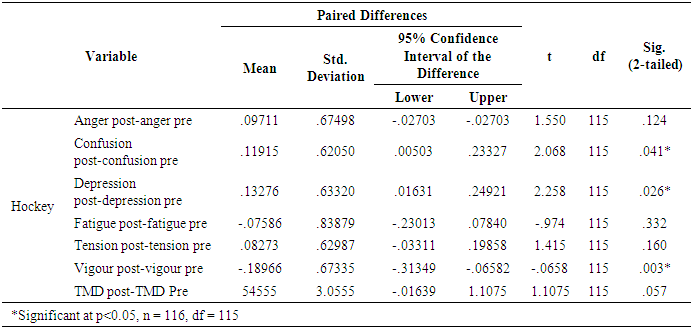

- The results of the analysis of the changes in the six mood states as well as Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) between pre-test and re-test of elite male hockey players are shown in Table 1.

|

= .11915, SD = .62050, t (115) = 2.068, p = 0.041). The level of depression increased and the change was significant (

= .11915, SD = .62050, t (115) = 2.068, p = 0.041). The level of depression increased and the change was significant ( = .13276, SD = .63320, t (115) = 1.550, p = 0.026). The level of vigour decreased and the change was significant (

= .13276, SD = .63320, t (115) = 1.550, p = 0.026). The level of vigour decreased and the change was significant ( = -.18966, SD = .67335, t (115) =-.0658, p = 0.003). These results suggest that there was significant increase in the level of confusion and depression while the level of vigour had a significant decrease. Changes in the other components of mood states (anger, fatigue and tension) as well as TMD were not significant.

= -.18966, SD = .67335, t (115) =-.0658, p = 0.003). These results suggest that there was significant increase in the level of confusion and depression while the level of vigour had a significant decrease. Changes in the other components of mood states (anger, fatigue and tension) as well as TMD were not significant.3.2. Change in Mood States of Elite Male Soccer Players

- The results of the analysis of the changes in the six mood states as well as TMD between pre-test and re- test of elite male soccer players are shown in Table 2.

|

= -.12956, SD = .70582, t (115) = -.1.977, p = 0.050). Fatigue level decreased and the change was significant (

= -.12956, SD = .70582, t (115) = -.1.977, p = 0.050). Fatigue level decreased and the change was significant ( = -.28559, SD = .96798, t (115) = -3.178, p = 0.002). These results suggest that the level of confusion and fatigue decreased and the decrease was significant. It is worth noting that this finding was as a surprise because negative mood states are expected to increase in relation to the training load. Changes in the other components of mood states (anger, depression, tension and vigour) as well as TMD were not significant.

= -.28559, SD = .96798, t (115) = -3.178, p = 0.002). These results suggest that the level of confusion and fatigue decreased and the decrease was significant. It is worth noting that this finding was as a surprise because negative mood states are expected to increase in relation to the training load. Changes in the other components of mood states (anger, depression, tension and vigour) as well as TMD were not significant.3.3. Mood States of Elite Male Hockey and Soccer Players

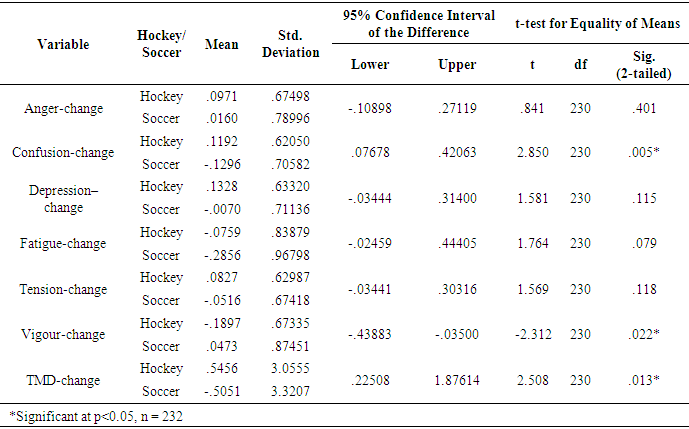

- To determine whether there was any significant difference in the mood state profiles between hockey and soccer players, an independent samples t-test was used and the results are presented in Table 3.

|

= .1192, SD = .62050) and soccer players (

= .1192, SD = .62050) and soccer players ( = -.1296, SD = .70582; t (230) = 2.850, p = 0.005). There was a significant difference in vigour change index between elite male hockey (

= -.1296, SD = .70582; t (230) = 2.850, p = 0.005). There was a significant difference in vigour change index between elite male hockey ( = -.1897, SD = .67335) and soccer players (

= -.1897, SD = .67335) and soccer players ( = .0473, SD = .87451; t (230) = -2.312, p = .022). There was a significant difference in TMD change index between elite male hockey (

= .0473, SD = .87451; t (230) = -2.312, p = .022). There was a significant difference in TMD change index between elite male hockey ( = .5456, SD = 3.05549) and soccer players (

= .5456, SD = 3.05549) and soccer players ( = -.5051, SD = 3.32072; t (230) = 3.32072, p = .013). Although the p- value of most of the sub-scales of anger, depression, fatigue and tension was not significant at p ≤ 0.05, except for confusion and vigour, the p-value of Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) was significant. Therefore, the null hypothesis that there is no significant difference in the mood state profiles between elite male hockey and soccer players in Kenya’s top leagues was rejected. These results suggest that the two groups (elite male hockey and soccer players) differed significantly in exhibited mood state profiles and the difference was in confusion and vigour markers as well as TMD. For example, from the descriptive analysis, the level of Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) increased for elite hockey players (

= -.5051, SD = 3.32072; t (230) = 3.32072, p = .013). Although the p- value of most of the sub-scales of anger, depression, fatigue and tension was not significant at p ≤ 0.05, except for confusion and vigour, the p-value of Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) was significant. Therefore, the null hypothesis that there is no significant difference in the mood state profiles between elite male hockey and soccer players in Kenya’s top leagues was rejected. These results suggest that the two groups (elite male hockey and soccer players) differed significantly in exhibited mood state profiles and the difference was in confusion and vigour markers as well as TMD. For example, from the descriptive analysis, the level of Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) increased for elite hockey players ( = .5456, SD = 3.0555) but decreased for elite soccer players (

= .5456, SD = 3.0555) but decreased for elite soccer players ( = -.05051, SD = 3.3207). This status was the same for vigour in which the scores showed the level decreased for elite male hockey players (

= -.05051, SD = 3.3207). This status was the same for vigour in which the scores showed the level decreased for elite male hockey players ( = -.1897, SD = .67335) but increased for elite soccer players (

= -.1897, SD = .67335) but increased for elite soccer players ( = .04773, SD = .87451). From the results, it is also observed that in all the six measures, the mean scores for hockey were higher though in some it was not significantly different from soccer.

= .04773, SD = .87451). From the results, it is also observed that in all the six measures, the mean scores for hockey were higher though in some it was not significantly different from soccer.4. Discussion

- The findings of this study showed that there was a high and significant level of confusion, depression and vigour among elite male hockey players. The high level of confusion and depression (negative mood states) could have been manifestation of increases in training load [18,20]. Notably, the level of vigour decreased and the change in mean POMS scores showed the change was significant. This is a normal occurrence since it has been noted that as training volume increases, the POMS profile changes with vigour decreasing [22,3]. Therefore, the decrease in vigour an indicator of positive mood state was also a sign of overtraining. Decreased vigour is a psychological sign of prolonged training distress [18,16]. The decrease of vigour suggests that there was an element of overtraining among hockey players. With increased training volume, the POMS profile changes with negative mood sub-scales increasing and vigour scores decreasing [10,18]. Despite the fact that the researcher had no control over other factors that can contribute to mood changes of the players participating in the study, significant changes in the POMS suggest that hockey players training in Kenya predisposes them to a profile that could be interpreted as commensurate with overtraining. The current study suggests that the increased training load between pre-test and re-test results in a change in POMS as reflected in high levels of confusion, depression and vigour. However, the paucity of related research with regard to hockey and mood states demands further scrutiny.The findings of this study showed that the level of anger, depression, tension, vigour as well as TMD all changed but the change was not significant among soccer players. This is a normal occurrence where the mood states change in relation to increases in training load. Study findings indicated that the level of confusion and fatigue decreased and the decrease was significant. The finding was against the norm where confusion and fatigue (negative mood states) are expected to increase in athletes following an intensive training [14,5,9,8]. Therefore, the finding was a surprise because negative mood states are expected to increase in relation to the training volume. A major interest of this study was to determine whether there was any significant difference in the mood state profiles between elite male hockey and soccer players. Despite the two sports having similarities in terms of team composition, players’ designated roles, starting status and being grouped under team sports, there are limited studies that have compared the mood state profiles of the two sports. The findings provided no support for the hypothesis that there is no significant difference in the mood state profiles between elite male hockey and soccer players in top national leagues in Kenya.

5. Conclusions

- The prevalence of psychological markers of confusion, depression and vigour was significant among elite male hockey players. The high level of confusion, depression (negative mood states) and decrease of vigour (positive mood state) was a clear manifestation of increases in training load. This implies that there was an element of overtraining among elite male hockey players. Confusion and fatigue showed significant changes in elite soccer. The significant decrease in levels of confusion and fatigue (negative mood states) among soccer as measured by POMS needs further scrutiny as research has shown that the two mood states are expected to increase in relation to training volume. The two groups (elite male hockey and soccer players) differ significantly as far as mood state profiles are concerned. However, it is worth noting that overtraining is not a function of psychological manifestation only since there are physiological, biomechanical and social factors that may affect the mood states. Although there is no single universally agreed diagnostic index of overtraining, the influence of other factors was beyond the scope of this study.

6. Recommendations

- The study results indicated that the two groups (elite male hockey and soccer players) differ significantly as far as mood state profiles are concerned. Therefore, it is recommended that while assessing the mood states, the coaches and other stakeholders should consider the task specific nature of the sporting activity being investigated.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML