-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2019; 9(1): 8-16

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20190901.02

Constructing Agents of Change through the Model of Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR): A Study of Physical Education in East Timor

Céu Baptista1, Teresa Dias1, 2, Nuno Corte-Real1, Cláudia Dias1, Leonor Regueiras3, Artur Pereira4, Tom Martinek5, António Fonseca1

1Center for Research, Education, Innovation, and Intervention in Sports, Faculty of Sports of the University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

2Center for Research and Intervention in Education, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Porto, Portugal

3Nun'Alvres Institute, Santo Tirso, Portugal

4Faculty of Sport Sciences and Physical Education of Coimbra, Portugal

5Kinesiology, University of North Carolina of Greensboro, USA

Correspondence to: Céu Baptista, Center for Research, Education, Innovation, and Intervention in Sports, Faculty of Sports of the University of Porto, Porto, Portugal.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This work intends to share the implementation process of the Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR) in East Timor, in two instances: first, with future teachers using a model of experiential learning; and, second, among elementary school students whose teachers, from 1st to 6th grade of elementary school, were those involved in the first stage of the study. Qualitative methodologies were used to monitor the entire process. Were interviewed 15 students of teacher education in each stage of this study. The participants evidenced learning and behavioral changes. The participants pointed out the lack of theory in the teaching of PE as a weakness. Emerging from the actors' discourses, this study showed the importance of this intervention in young people and allowed to identify the strengths and weaknesses that students felt when they experienced and applied a model TPSR that resorts to different dynamics and practices.

Keywords: Youth, Physical education, Teaching, Responsibility model, East Timor

Cite this paper: Céu Baptista, Teresa Dias, Nuno Corte-Real, Cláudia Dias, Leonor Regueiras, Artur Pereira, Tom Martinek, António Fonseca, Constructing Agents of Change through the Model of Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR): A Study of Physical Education in East Timor, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 8-16. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20190901.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Teachers’ training presumes a continuous development where the teacher is responsible for her/ his own professional development. In this process, there must be continuous self-reflection, critical thinking and a permanent updating of skills. It is also important to endlessly seek for innovation (in pedagogical terms, in relational strategies and in technical issues related to the area of knowledge), allowing individual and teamwork improvement, when considering school and educational contexts.Teachers must themselves be agents of continuous training, who must regard teaching as a factor of change and innovation, at different levels of learning and giving significance to the acquisition of reflection skills, assuming the challenge of being flexible and having the ability to adapt themselves to educational issues that characterize different generations of pupils and students. Only in this way is she/ he contributing to the personal and social attributes of their students throughout life. Being a teacher starts with an university degree, but it must be considered a process over lifetime.In this line of thought, when it is referred that young adults are being trained to become teachers, it is important to consider as one of the major goals in her/ his initial degree to develop self-reflection skills about the process of teaching, as well as to create opportunities for future teachers to develop a continuous process of evaluation and reflection of performance, with the definition of professional plans that define, for each year, the goals for improvement and updating.However, teachers’ training is not a linear process of teaching and learning by itself. A well-designed curricular plan in university does not guarantee good teachers, but rather it is important to refer that the quality of teachers is also a result of their training and experience [36].It is imperative that teachers’ training prepare the future teachers not only for teaching, but also to answer to societal fluctuations that appear in the present and in the future. This new generation of teachers that are being shaped must be able to act in different contexts and realities and, consequently, to adapt the fundamental contents to be taught to these fluctuations and pupils/ students. This structure of the curriculum has to consider that the characteristics of society in the 21st century are very different from the characteristic in the seventies or eighties. Starting from this presupposition, it is possible to perceive the importance of this process (teacher’s training) not only for the individual lives of students and teachers, but also for their societal life and its social and economic development [36].In this sense, it is necessary that future teachers have the ability to adapt their knowledge, methodologies and principles to the reality in which they are placed and not limit themselves to narrating knowledge and techniques [14], as if the students were the listeners of a radio where the person who broadcasts the program does not know who is listening to it.The introduction of new teachers in the workplace is a global challenge and, therefore, universities should be aware that, in the first instance, they are responsible for the change and/ or evolution, or not, of the societies in which they are inserted, and they do so, for the most part, through teacher training.The knowledge to be conveyed goes beyond general or specialized, technical or tactical, and literary or scientific knowledge. Teaching, regardless of the subject, must have intentionality, a set of processes and psychological attitudes that are indispensable. For this, the acquisition of personal and social skills that allow solving life situations in a more flexible and creative way possible is important (5). The best vision we can provide to future teachers is to make them live experiences that lead to justice and cooperation, rather than teach them what justice and cooperation is.

1.1. Timorese Population, Quality of Teaching and Learning Experiences

- Timor-Leste was invaded by Indonesia after it became independent from Portugal in 1975. By the end of the colonial period, in 1975, the illiteracy rate in Timor-Leste was estimated to be 90 percent [43]. In the ensuing 24 years of the occupation by Indonesia, Timor-Leste remained the second poorest province of Indonesia. During this occupation, the Indonesian education system replaced the Portuguese system, and Bahasa Indonesia became the language of instruction when the Portuguese language was banned.After its independence, in 2002, Timor-Leste was one of the poorest countries in Southeast Asia [44]. The educational process has been restructured in all areas, but it has been a very slow process, and even more time consuming, due to its particularities, in the restructuring of human resources with respect to teachers’ training, although the Government and politicians have invested for an increase in literacy [4].As in any post-conflict country, it is common for women to be the main caregivers of children, a responsibility that has been intensified by extensive loss of family and social support, as a consequence of recurrent periods of mass conflict. Poor access to, and ongoing taboos against family planning, and consequent high fertility rates, add to the pressures mothers experience in relation to child-bearing and child-rearing [37].Considering the past, but looking toward the future of the nation through different international reports [43] and national documents, such as the Strategic Development Plan 2011-2030 [28], which foresees a change in education policies and consequently in the Basic Education Law, teacher training plays an important role in social construction, since the level of academic literacy is considered a pillar of the development of society to improve the quality of life of Timorese people.According to article 25 of the Timorese Minor Protection Code young people are entitled to a quality education in an environment conducive to learning. In this sense, there is a strong concern on the part of the governing authorities to increase the quality of education, focusing greater relevance on the training of teachers and, at short-, medium- and long-term, in the Strategic Development Plan 2011-2030 [28].This development implies, in a sense, the need to break free from methodologies and strategies that have been observed over the years, such as the belief that teaching must be centered on the teacher, as well as the authoritarianism imposed on students in the classroom which, in turn, generates fear of participating, intervening or even sharing their opinions. On the other hand, there is a great lack of opportunities, whether sportive, social or professional, which, taken together, leads to the Timorese youth growing up in the midst of a “youth accustomed to poor quality education and without academic rigor” [6]. Therefore, a change in teaching pedagogies will not be expected in the immediate future and they will be even more difficult to find in the long-term, unless we are not indifferent, and the willingness to act by universities, supported by educational policies, speaks louder.It is the mission of the universities, and of their professionals, to act as agents of social change with the teachers, students and communities, not only in order to suppress the immediate needs and problems, that is, keeping the schools open ensuring “teachers are only present body”, but they should also be the first to use dynamic methodologies and demand learning models based on learners’ autonomy and independency, as well as on their ability to actively construct their own learning process. Students should be valued when they are capable of consciously controlling their learning processes and of caring for others, when they are able to acquire knowledge in personally meaningful ways and are, therefore, better able to achieve superior academic results, as well as being more active in society.

1.2. The Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR) Model

- “Teaching values is one thing. Getting students to apply them outside of class is another” [27].Several studies indicate that children who are physically active and influenced by positive experiences become active in the future, particularly in adult life [3]. In addition to this reason and given the particularities of Physical Education (PE), the teacher is aware that when playing, youth learn to assume duties and responsibilities with themselves, and then with others. Through these activities, young people will interiorize rules and principles that will be part of their personality in the future.However, some studies (e.g. [8]) tell us that changes within school programs do not provide automatic changes in educational praxis. The success of educational reforms depends on the pedagogical perspective shared by teachers and how it is shown in praxis. Shulman suggested that teaching “begins with a teacher’s understanding of what is to be learned and how it is to be taught” [38].The TPSR model, developed by Hellison in the seventies [16] and solidified over time [17-19], is an example of an active model which intends to teaching and promoting of values, character, life skills and responsibility through physical activity [31, 35]. It is possible to find in the literature some studies that have questioned the efficiency and the applicability of the TPSR model, generating a wide theoretical basis of the TPSR model as a solid positive development program through physical activity [10, 19, 20, 23, 35, 45]. The focus of TPSR is to foster life skills and values through physical activity, thus, physical activity is regarded as a vehicle and a pedagogical instrument that teaches values to these young people, which they can apply to other areas of their lives.The PE classes based on the TPSR model have a progression of responsibilities that lead to the major goal which is of helping to lead with others. The levels of responsibility considered are respect for rights and feelings of others, participation and effort, self-direction, leadership and helping others, and transfer outside the gym.The first level, respect for rights and feelings of others, is characterized by the adoption of behaviors and conducts such as respect for others, listening and paying attention to the teacher, resorting to dialogue to solve problems in a pacific way, not interrupting teachers or classmates. The second level, participation and effort, is characterized by the participation and effort from each student in the completion of different tasks, such as performing an exercise until the end, participating in all activities and following the established rules. The third level, self-direction, intends to teach students to become more independent, responsible and demanding through their learnings, for example, to take responsibility for their actions, to continue tasks even without the supervision of the teacher, to manage time and plan their self-learning. Self-direction may be understood as a “pop-psychology” message: “Take charge of yourself and your problems will disappear” [22]. The fourth level, leadership and helping others, is characterized by developing the ability of students to consider the welfare of others as important. Finally, the fifth level, transfer outside the gym, characterized by applying their learning in the last four levels to different contexts and physical spaces (outside the PE space) or to different contexts of their lives.The guidelines for TPSR-based lessons involve a typical format [18] a) relational time, a brief time in which the teacher interacts with participants and mentions something special to them, b) awareness talk, a more formal moment in which the teacher has a brief conversation about the levels of responsibility that will be developed in the classroom and sets concrete goals, c) physical activity plan, it occupies the most time, and all tasks have connected levels of responsibility, d) group meeting, gives participants practice in values through a democratic way. The purpose of this part is to give participants the opportunity to express their feelings and their points of view about the day’s lesson, and e) reflection time, teacher and participants share their feelings, thoughts, and behaviors.

2. Method

2.1. Implementing and Evaluating the TPSR Model

- TPSR model is not a recipe where it is possible to simply put together all the ingredients to get good results. As mentioned by Hellison [19], we should take the guidelines and have the courage to generate our own model [7].Based on the mainstream of this added value of TPSR, several authors adapted the model to their proximity contexts, such as school PE programs, community centers, and summer camps [21], but also to their amplified social and cultural reality, such as different countries: Ireland [15]; Portugal, Indonesia, Mexico and Spain [26]; New Zealand, Brazil, South Korea and Canada [12]; Nepal, South Africa [13]; China [33]; and East Timor [1].Believing that “really good youth development happens when youth and communities develop together, not separately” [24] and with the opportunity to intervene with a teacher training program in East Timor, we framed the “TPSR Teacher Questionnaire” [18] to follow Hellison’s initial idea when defining these guidelines for TPSR: “one way to teach – is for each of you to develop your own model of teaching” [22].The program was implemented with a specific population in future 1st to 6th grade elementary school teachers. A three-way agreement was made between the National Institute for the Training of Teachers and Education Professionals of East Timor, the University of Minho (Portugal) and the Ministry of Education of East Timor to implement this program in two curricular units of the official program. This intervention was done only in PE subjects (PE I and PE II), in its methodological component. The proposal was to bring new challenges by intensively reinforcing the practical approach of the curricular units and providing a large number of sport experiences and consequently, by using an experiential learning approach, make this teaching methodology more inclusive, as its focus is on the student as an individual.The intervention had an implementation period that began in July 2013 (3rd semester) and ended in December 2014 (6th semester). It is important to mention that the last semester (August – December 2014) corresponded to the autonomous implementation of the program (to which the students had been exposed, according to the experiential learning model) by them during their Pedagogical Practice in an internship (with provided supervision) in schools.Over the program implementation, 68 sessions were conducted between July 2013 and July 2014, with the purpose of the initial session being to meet students and explain the objectives and purposes of the TPSR model, its implementation during these units and framing the research goals. In the 3rd semester, 38 sessions of 180 minutes took place weekly. In these sessions, the modalities taught were handball, gymnastics, swimming, athletics, korfball and one optional sport (aerobic dance, futsal, volleyball or basketball). In extracurricular time, it was proposed to students to conduct a tournament (between classes) with the modalities of volleyball, futsal and basketball divided by gender. This activity was developed with students’ collaboration during the entire process and had the approximate duration of two months. The major goal was that students could easily put into practice each of their learnings and understand/reflect on how important it is to get involved and take advantage of having experiences that in the future they may want to implement with their pupils.In the 4th semester, ten weekly sessions of 180 minutes were conducted. The first sessions have a theoretical-practical dynamic to allow addressing concepts of planning. Despite this theoretical approach, students were challenged to design a peer-teaching methodology for children at an elementary school thinking that their project proposal would be implemented in the following semester, with pupils at school. To develop this project, they had to follow some criteria a) to develop a physical activity outside the class but within the facilities of the training center, or in public or private schools or in community spaces); b) it had to be implemented in a group; c) it had to describe all the planning (location; number of sessions; content/ sport modality; material to be used; number of pupils for each moment; differentiated strategies to include everyone).In the 5th semester, 20 sessions of 90 minutes were completed. In curricular time, students taught a PE class at a public elementary school, and this brief internship was coordinated and taught in Portuguese classes and with Portuguese teachers but following the national curriculum of East Timor. During this semester, in extracurricular time, usually on Saturday, the groups were responsible for developing the project designed in the 4th semester.

2.2. Research Goals

- Considering the cultural framework in which the intervention was developed, researchers expected some constraints, therefore it was assumed that they would have to adopt a “trial and error” dynamic and flexibility in the process and strategies, which would allow to deal with unforeseeable situations. Keeping this in mind and with a very profound knowledge of the TPSR program, the major goal of this research was, undoubtedly, to promote personal and social responsibility in future teachers through the subject of PE, always valuing students as individuals, and taking into consideration that East Timor was, at the time, a post-conflict society with a strong deficit in terms of the qualification of teachers. The objectives that underpinned this research pillar were: 1. Analyse students’ perception (as future teachers) of learning and change when using the TPSR model; 2. Identify students’ perception about the strengths and weaknesses of the TPSR model.

2.3. Methodology

- Qualitative methodologies were used to monitor the entire process [9]. The interview used in this study for emphasizes the focus on the process and not the product, promoting the interaction between different agents of the study. Pursuing the objectives defined for this study, “… the qualitative methodology allows? inquiry and selected issues in great depth with careful attention to detail, context, and nuance; that data collection need not be constrained by predetermined analytical categories to the potential breadth and depth” [34].

2.4. Context and Sample

- The size of the sample is flexible allowing it to be adjusted and adapted based on what is learned during fieldwork. Usually, it depends on the research objectives, why they were defined, how the outcomes will be used, and what resources (including time) researchers have for the study, being that there is no rules for sample size in qualitative inquiry [34].This study used a sample with some characteristics that would allow researchers to follow the participants throughout the entire process and complete the main goal of the study [40]. Three criteria were established a) participants who completed three interviews throughout the intervention (3rd, 4th and 5th semester); b) participants who were observed in their internships as PE teachers with one school group with a specific instrument of observation - Tool for Assessing Responsibility-Based Education (TARE) created by Wright and Craig [46] (although this is not considered nor reported in this article), c) participants who were willing to participate in all stages of the research process.Thus, 15 participants were selected (4 males and 11 female), ± 24 years old, all of them involved in the Project of Initial and Continuous Teacher Training (Course for teachers of 1st to 6th grade of elementary school) in Baucau (East Timor). It was not possible to guarantee gender balance because of the characteristics of the course. Indeed, the majority of the population getting this university degree are women.

2.5. Ethics, Validity and Reliability

- Before beginning the implementation of the program and subsequent data collection, the entire research design was approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Sport of the University of Porto. Information about the content and purpose of the study was shared to all participants and confidentiality was guaranteed, as they were informed that all data would be used exclusively for academic purposes.Some methodological considerations were made to strengthen the trustworthiness of this study, including the triangulation of categorization, content analysis and coding analysis [41]. Two researchers worked separately to stablish internal validity. For inter-coder reliability, two independent coding were performed from two interviews (10% to 20% of total sample according to Neuendorf [32]. The calculation of reliability was done with NVivo 11 through “Coding Comparison”, with the paragraph being considered the unit of analysis. The degree of agreement was calculated by Cohen’s Kappa .80 in all categories, p< .001 [39], exhibiting a very good agreement [25].

2.6. Data Analysis

- This study included 15 participants, each of whom went through three moments of interview throughout the data collection process, which allowed to have a universe of 45 semi-structured interviews. The guideline for these interviews was “a pre-planned interview guide to direct the interaction and relies predominantly on open-ended questions” [41]. According to the purpose of this study, the interviews were conducted to allow the participants to express their feelings and perceived value of the TPSR model in their teachers’ training, reinforcing Patton’s perspective that “interviewing with an instrument that provides respondents with largely open-ended stimuli typically takes a great deal time” [34].The interviews were conducted without compromising the description of the feelings, thoughts, and intentions of the participants. All interviews were recorded in audio and video to preserve verbal and nonverbal behavior and they were transcribed globally. NVivo 11 software was used to help organize and store all the data [34].For the definition of the categories, a deductive and inductive analysis was performed, ensuring the agreement between the two researchers and first authors. This process allowed to bring together previous research and literature in the definition of pre-defined categories [11, 41, 42] and highlight the richness of the students’ own discourse in the definition of emerging categories [42].As a predefined category, this study considered “Learning and Changes”, with the sub-categories “Learning and changes in ourselves”; “Learning and changes in others” and “Learning and changes in ourselves by others”. As emergent categories, it was possible to identify as a major category “Evaluation of TPSR model” with the following subcategories “Levels of responsibility”, “Strengths and Weaknesses of the model”, and “Cultural Aspects”.It is important to clarify that the sentences that are presented in this study could not always correspond to a direct translation of the narratives of the participants. This fact has to do to with the native language of most students in the study – their native language is Tetum, some of them understand and speak Portuguese reasonably well, the others were helped by a native who was present in the interviews and translated to Tetum and then to Portuguese. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that when the interviewer or the interviewees seemed to have any doubts about one idea or feeling, the questions were reformulated to guarantee that both sides understood. Although during the interviews the researcher used language that was clear, objective and as close as possible to the participants’ in order to avoid this difficulty of orality, when the students understood the question but gave brief answers or answers that did not answer the question, such as “Yes”, “No”, “I like It”, “I don’t like it” or others that emerged without arguments associated with them, a decision was made to not code. Therefore, it was a coding criterion that any answer to each question must be expressed with examples.

3. Results and Discussion

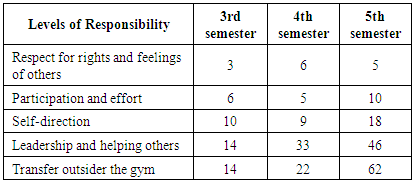

- Seeking to understand the contributions of the TPSR model to teacher training, the results were organized in three different but complementary parts, given the initiation and practical character with which the participants showed their learning and behavior changes. The participants assumed themselves as active throughout training, thus they evaluated the intervention through the strengths pointed out and the aspects deserving reflection, with it being impossible to dissociate from a third part, the cultural aspects.The fact that participants experienced the learning of sports with an exclusively experiential methodology proved to be a very positive point. The practice allowed significant improvements at the physical-motor level and with respect to health issues: “About volleyball, also futsal basketball and other that we also learned in Timor-Leste, learn but only theory…” (C., 3rd semester, male), “… because through physical education class we can train and think and my illness decrease…” (H., 5th semester, female).More frequently mentioned by the participants were behavioral and attitude changes that will help them in the future as teachers and citizens: “… if I do not arrive late and complete goals I can change my attitude, maybe… last year I saw, I do not have a bit of responsibility, but through goals I could improve that." (H., 4th semester, female), “During PE classes about responsibility I learned how to be responsible at work and also how to be responsible when in the future we will be teachers and have to take responsibility with the pupils” (D., 3rd. semester, male).These improvements and changes in behavior were felt by the participants themselves but also referred when they talk about other colleagues: “Until high school I never worry about anything that happens even problem, I do not worry about anything. Never think responsibly for my life or for myself but when I learned PE about the goals is not much for responsibility but little by little I start already to change my attitude about responsibility.” (H., 3rd semester, male), “many students who have change from the 3rd to the 4th semester, through methodology II of physical education I think it helps all students because of practicing the project in another school, forces to speak Portuguese language.” (T., 4th semester, male), “all participate and in this participation the leader also has to give courage. All colleagues participate in the project in the activities we developed in the projects, at the beginning colleagues some (…) do not give importance, (…) but then I called attention to them, and they began to change their attitude.” (D., 5th semester, male).Finally, the improvements and behavioral changes were observed in the participants by other colleagues or teachers: “There are colleagues and also some teacher who tells me that already improved some activity or (…), another subject” (H., 3rd semester, male), “In my team, my leader says that I already reach some goals” (T., 5th semester, male).The levels of responsibility were the guiding lines to consolidating the values learned in the sessions (such as the peaceful resolution of conflicts) and in the acquisition of the intrinsic values of their own levels of responsibility. However, the interpretation of the data regarding levels of responsibility must be careful to the point of not “assigning/fixing” a level of responsibility to the perception of the participants after the interview, since the interview script had this purpose, not directly contemplating the levels of responsibility.The intervention had a cumulative and progressive direction in the acquisition of levels of responsibility over time, such is perceived in the third semester where the intervention focused, in general, on all levels of responsibility. In the fourth semester, the intervention focused mainly on level four (leadership and helping others, for example, peer-teaching, teamwork in the preparation/organization of the project). In the last semester of the intervention, the intervention succeeded in transferring what was learned during the program to the community, for example, when the students, as teachers, taught a class of physical education to students in 1st to 6th grade and their project independently.The results of the study indicated that the intervention went according to what was previously outlined for the acquisition of levels of responsibility, as can be seen through the frequency of speeches by the participants, in each semester, where they are at a certain level of responsibility. Thus, it was possible to verify that the speeches had a similar frequency (coding) in levels three, four, and five in the third semester, a higher frequency for level four in the fourth semester, and higher frequency for level five in the fifth semester (Table 1).

|

4. Conclusions

- It was proposed in this study to analyze the perceptions and concerns of university students (as future teachers) regarding their learning experiences related to the subject of PE. Moreover, it was proposed to identify these students’ perceptions about the strengths and weaknesses of an intervention based on the TPSR model within the framework of teacher training in East Timor.The TPSR model served as a resource that supported the teaching of PE, according to the Basic Education Law in East Timor, which states that teaching (in general, not only PE teaching) must promote “the global development, full and harmonious of the personality of individuals, encouraging the formation of free, responsible and autonomous citizens” (article 4, Section II, Educational Policies, as of January 6, 2018) and, on the other hand, it is aligned with the Strategic Development Plan (2011–2030) of this country, where it is referred that one important goal until 2030 is to increase the amount of teachers properly qualified for the exercise of teaching.With regard to the evaluation of this kind of intervention, based on experiential learning, this study proved to be a very enriching experience for all participants, and the majority of participants mentioned as positive the fact that the process had been implemented with a practical methodology, although 50% of the participants pointed out that the theory should appear to complement the practice in PE teaching.Furthermore, the intervention proved to be an added value for the development of the Portuguese language, as it was part of the lesson at least in the moments of group discussion.One of the weaknesses most referred by the participants is not directly linked to the intervention but, in a certain way, to the educational policies inherent to the system already implemented, where they mentioned that the number of hours per week designed for the PE subject should be increased.In conclusion, it seems to be vital for the East Timor government, when reflecting on educational policies, to consider that universities prepare teachers to answer to the demands of schools, teachers, pupils and parents, but this also implies that universities should be able to develop skills of critical thinking and flexibility in their students and future teachers to deal with different experiences and contexts throughout their career, that is, teachers must be able to function in the current system, but at the same time be able to question and act as active people in order to change and transform their praxis inside PE.For future studies, it seems important to do a follow-up in order to understand whether these participants apply, as teachers, the learned strategies that aim to promote personal and social responsibility in their pupils. Another aspect worthy of attention for future investigations that was not considered in this study, but was one of our reflections, is to consider a multidisciplinary engagement.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML