-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2018; 8(4): 118-123

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20180804.02

Levels of Anxiety: Practice vs. Competition in NCAA Division I North American Football Players

Jacob Allie1, Abigail Larson2, Mark DeBeliso2

1Assistant Football Coach, Lindbergh High School, Renton, USA

2Department of Kinesiology and Outdoor Recreation, Southern Utah University, Cedar City, USA

Correspondence to: Mark DeBeliso, Department of Kinesiology and Outdoor Recreation, Southern Utah University, Cedar City, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

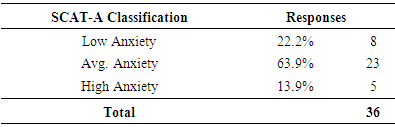

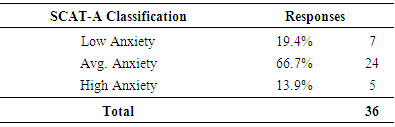

High levels of cognitive and somatic anxiety may be detrimental to sport performance as well as increase risk of sport-related injury. It is important to identify situations that are likely to cause high levels of anxiety so appropriate self-regulation and anxiety management techniques can be employed. PURPOSE: The purpose of this study was to 1) determine if anxiety level differs between NCAA Division 1 North American football players based on position played and 2) determine intra-individual and inter-position differences in anxiety level prior to a scrimmage versus a practice scenario. METHODS: NCAA Division I North American football players (n=36) completed a modified Sport Competition Anxiety Test (SCAT-A) survey prior to a practice session and again prior to a scrimmage. RESULTS: The results of the SCAT-A were first sorted by anxiety category (low, average, and high) and subsequently sorted on position: offensive player (OFF)/defensive player (DEF), as well as high contact (HC)/low Contact (LC). A Fisher’s exact statistical test was used to make 6 different comparisons based on position and scenario. Anxiety categories were compared between OFF and DEF for the practice session as well as the scrimmage. Likewise, anxiety categories were compared between HC and LC for the practice session and the scrimmage. Finally, anxiety categories were compared within groups for OFF and DEF between the practice session and the scrimmage. No statistical differences in anxiety categories were found between positions or between the practice and the scrimmage (p>0.05). CONCLUSIONS: Within the parameters of this study, contrary to the research hypothesis, anxiety levels do not appear to change based on position or the competitive scenario.

Keywords: Sports Competition Anxiety Test, SCAT, College football and anxiety

Cite this paper: Jacob Allie, Abigail Larson, Mark DeBeliso, Levels of Anxiety: Practice vs. Competition in NCAA Division I North American Football Players, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 8 No. 4, 2018, pp. 118-123. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20180804.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- State anxiety is considered to be a specific, situational, negative emotional response that can occur in conjunction with competitive stressors [1]. Research has shown a correlation between an increase in state anxiety and a decrease in athletic performance [2]. Anxiety can be further classified as cognitive or somatic. Cognitive anxiety represents the mental manifestations of worry and self-doubt. Cognitive anxiety is often due to unrealistic beliefs, previous poor performance, belief that a poor performance is eminent, and a diminished sense of self-efficacy as it relates to the implementation of necessary sport skills [3, 4]. Somatic anxiety is considered to be a state anxiety which is defined as a temporary condition in response to a perceived threat and specifically relates to the body’s physical response to a stressor [5, 6]. Symptoms of somatic stress include hyperventilation, increased heart rate and blood pressure, sweating, and muscle stiffness and soreness [3, 4]. Cognitive and somatic anxiety can be manipulated independently of each other and can have different impacts on performance [4]. Many athletes experience somatic anxiety during high-pressure situations such as prior to a game or scrimmage or in the later portions of a close competition. Prior research indicates that somatic anxiety levels are highest a week prior to and two hours prior to competition; post-competition, somatic anxiety levels drop [7]. It has been shown that somatic anxiety may hinder an athlete’s performance although to a lesser degree than cognitive anxiety [4]. Additionally, somatic anxiety has been associated with hostile aggression as well as passive aggression during a sporting event [8]. The coach can play a pivotal role in helping players recognize and minimize competition anxiety [9]. As such, it is important for coaching staff to understand mediators and moderators of competition anxiety as well as how somatic and cognitive anxiety can negatively affect an athlete’s performance and mental wellbeing. Numerous studies have documented the various forms of anxiety as well as the potential effects of heightened anxiety on sport performance [2, 7, 8, 10-16]. Based on this research it has been determined that athletes who have strong self-control strength are less likely to experience a decrease in skill performance when anxiety level is high, compared to athletes who have low or depleted self-control strength [10]. It has also been shown that anxiety levels may be lower in college team sport athletes compared to individual sport athletes [11]. Age, sport experience, sport ability, physical condition, body attractiveness, strength and general physical competence have also been shown to be important factors in determining competition anxiety [12]. Although numerous studies have examined the determinants of competition anxiety [3, 15-19], there is a lack of research identifying who is predisposed to competition anxiety based on sport or position played. A better understanding of these factors may allow for the implementation of intervention strategies to mitigate heightened anxiety levels.There is growing evidence that suggests a relationship between performance, somatic anxiety, cognitive anxiety, and self-confidence [10-12, 14, 17-19, 24]. The aforementioned relationships may provide guidance for coaches with regards to strategies for the effective management of an athlete’s anxiety levels (and self-confidence) with the goal of enhancing the athlete’s performance [11, 12].North American football is a highly popular sport in North America with participants ranging in age from children to mature adults. Determining sport-specific factors associated with increased levels of anxiety, such as position played, level of contact, and play scenario may allow for improved utilization of sport psychology techniques designed to reduce competition anxiety. Ultimately, reducing competition anxiety has the potential to improve level of play as well as mental well-being would be of value to the athletes and their respective coaches. Hence, the purpose of this study was to determine if anxiety levels vary as a result of position played or play scenario (practice or a scrimmage). We hypothesized that anxiety levels would change based on the position that an athlete a played as well as play scenario (practice or a scrimmage. Specifically, it was hypothesized that high contact positions would experience greater levels of anxiety than low contact positions, offensive positions would experience greater levels of anxiety than defense positions, and greater levels of anxiety would be experienced prior to a game like situation as opposed to practice.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

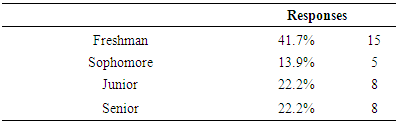

- The participants were players from a Division 1 North American football program. After IRB approval, participants were recruited via a short presentation that explained the study purpose and procedures. Volunteers who agreed to participate completed an informed consent prior to providing any additional information. No compensation was provided for participating in the study. Thirty-six questionnaires were completed and useable for the study. All athletes that participated in the questionnaire (n=36) were males age range 18-26 years. The majority of the athletes surveyed were identified as freshman (41.7%).

| Figure 1. North American Football helmet. Image with permission of Southern Utah University Athletics |

2.2. Instrument

- A modified version of the Sports Competition Anxiety Test (SCAT) was used as the survey tool. The SCAT test was initially developed to measure an athlete’s competitive A-trait anxiety [4] but was subsequently determined to measure primarily somatic anxiety levels [20]. The test-retest reliability of the SCAT has been documented to range from r= 0.73-0.88 and an internal consistency or r= 0.95-0.97 [4]. There are two versions of the SCAT test, SCAT-C, which has been validated in children aged 14 and younger and SCAT-A, which is intended for use in individuals 15 and older.The test administered was a modified version of the original SCAT-A test. This version contains the same questions in the same order but omits words such as “anxiety” in an attempt to garner honest and unbiased self-assessments. The modification to the survey itself had no impact on the grading scale because it queried the same information in the same order.

2.3. Procedures

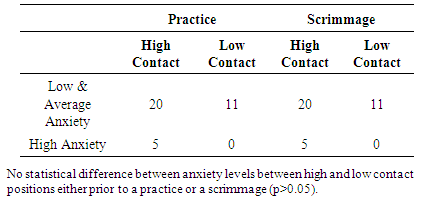

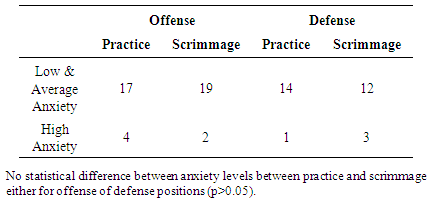

- The SCAT-A survey was administered twice to the same athletes on two separate occasions. Once prior to a practice and again prior to a scrimmage. In both situations, upon arriving in the locker rooms, each player had a survey and a pen in their respective locker. During the first round of administering the test the players filled out the survey while preparing for a practice. After all surveys were completed and collected, each was scored. Once scores were tallied, surveys were classified as high level of anxiety, an average level of anxiety, or a low level of anxiety. This test was then administered again approximately two weeks later with the same athletes but this time prior to a scrimmage. Once again, the survey and a pen was placed in the player’s locker prior to their arrival. Following the completion of the surveys, they were again collected and scored using the same grading scale. The two scenarios that were used in this study were a practice and a game like situation. The first scenario was a familiar basic practice session that had been conducted numerous times throughout the spring football schedule. This practice was a noncompetitive environment that focused on learning and developing skills and fitness. The game-like scenario was a scrimmage where the team was split into two and competed against each other and was aptly named the “Spring Football Game”. The game followed all standard rules of play.For the purpose of this study the participants were also categorized as either a High Contact (HC) or a Low Contact (LC) position. The HC positions included running backs, tight ends, offensive lineman, defensive lineman, and linebackers. The LC positions included defensive backs, wide receivers, and quarterbacks.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

- Each SCAT-A questionnaire was scored and categorized as low, average, or high anxiety levels. In order to analyze the survey results the data was collapsed into two categories: low and average anxiety combined compared to high anxiety. A Fishers exact test was used to compare anxiety levels between: HC vs. LC during practice and the scrimmage, OFF vs. DEF during practice and the scrimmage, as well as practice vs. scrimmage for OFF and DEF (four between group and two within group comparisons). The statistical analysis was carried out with an Excel spreadsheet prepared by McDonald in the Handbook of Biological Statistics (2009) [21]. Statistical significance was considered as α≤0.05.

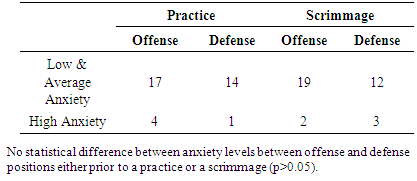

3. Results

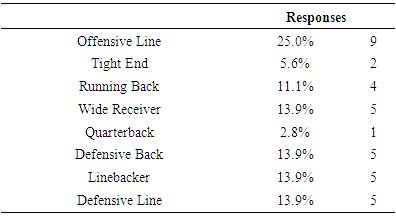

- Table 1 summarizes the sample’s experience in terms of football eligibility year. Approximately 58.3% (n=21) of the college athletes identified themselves as an OFF player and 41.7% (n=15) of these athletes identified themselves as being a DEF player. The OFF players included wide receivers, running backs, offensive lineman, tight ends, and quarterbacks. The DEF positions included defensive backs, defensive lineman, and linebackers. Number of participants within each position is summarized in Table 2.The majority of the participants in the study were identified as playing a HC position (i.e. offensive lineman, defensive lineman, running backs, linebackers, and tight ends) (69.4%; n= 25) compared to playing a LC position (i.e. wide receivers, defensive backs, and quarterbacks) (30.6%; n=11).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The purpose of this study was to investigate if anxiety levels differ among NCAA division I North American college football athletes based on position played and/or play scenario (practice versus a scrimmage). Positions were broken down into OFF and DEF as well as HC or LC. The hypothesis was that anxiety levels would change based on the position the athletes played and that anxiety levels would also change based on a practice scenario vs a scrimmage. The results of the study did not support either of the aforementioned research hypotheses.The data collected in the current study confirms the results of previous research [8, 11]. The high number of athletes experiencing average and low anxiety levels in the current study is in agreement with other research that suggests low and medium anxiety levels are most common in contact sports [7]. Howard Zeng [11] conducted a study using the SCAT on collegiate athletes and compared anxiety levels in team sport athletes and individual sport athletes. The results showed team sport athletes had lower levels of cognitive and somatic anxiety compared to individual sport athletes [11]. This could explain why the majority of participants in the present study had low to moderate levels of anxiety.Additionally, a study conducted by Bozkus et al. [12] examined the age and experience of athletes to determine any correlation to anxiety levels as measured by SCAT. The participants within that study were professional premiere league female soccer players. Results indicated that age, sport experience, sport ability, physical condition, body attractiveness, strength, and general physical competence were all important factors in determining competition anxiety [12]. These findings support the results of the current study in that attributes of the sample tend to be those that are associated with lower competition anxiety. Collegiate athletes are likely to be highly proficient in their sport ability. Additionally, collegiate athletes are also required to participate in programs that increase their physical conditioning and their strength, which based on previous studies can have an impact on reducing somatic anxiety levels [12]. In the current study somatic anxiety levels in collegiate athletes did not differ prior to a practice versus a game like situation, which is in contrast to other study findings [7]. This lack of agreement may be due to the athletes perceiving both conditions (practice scenario vs a game like situation) as non-discernable in regards to saliency. The majority of current theories regarding anxiety in sports are mainly focused on how anxiety level affects sport performance [2, 10, 12-14, 18]. Burton [22] and Krane [23] found that cognitive anxiety and athletic performance were negatively correlated, while Gould [24] found that there was no relationship between cognitive anxiety and performance. Krane [23] also found a negative correlation between athletic performance and somatic anxiety. A meta-analysis was conducted by Craft el. 2003 to compare the findings of multiple studies and results of the analysis showed that the best way to predict athletic performance is by assessing an athlete’s self-confidence [13]. This same meta-analysis found that performance was more negatively affected by both somatic and cognitive anxiety in athletes with a lower level of skill compared to athletes with a higher level of skill [12]. The present study was conducted in an effort to try and determine if there is a relationship between anxiety level and position played and/or play scenario (practice vs scrimmage). Having insight regarding when an athlete will experience higher or lower anxiety levels could help coaches and athletes develop coping strategies in order to effectively manage anxiety levels and perform optimally. There were several limitations while conducting this study. The participants who took part in this study were predominantly freshman (≈42%) and the SCAT-A questionnaires were administered in the off-season rather than the in-season. The scrimmage had playing time implications but was not a true in-season game. Additionally use of the Fischer’s exact test when making the within group comparisons can be overly conservative [21], however the results of the within group comparisons were far from achieving statistical significance (OFF practice vs. game: p=0.66, DEF practice vs. game: p=0.60). Future research may resolve this issue by collecting baseline assessment of athlete anxiety level in the post-season or by using an ultra-highly competitive scenario such as a conference championship game. The final limitation worth addressing is the SCAT instrument itself. The SCAT-A instrument has been developed to assess competitive A-trait anxiety [4]; however, subsequent analysis has shown the SCAT-A to primarily measure somatic anxiety levels [20]. Future research should consider using another instrument in addition to the SCAT, such as the Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 test (CSAI-2), as a means to measure somatic anxiety, cognitive anxiety, and self-confidence. Likewise, future research should consider use of the Sport Anxiety Scale-2 (SAS-2) instrument which reports cognitive and somatic anxiety levels in athletes [20]. There is a growing concern regarding relying solely upon statistical significance (i.e. p-values) when examining the results of a research effort [25]. As such, the American Statistical Association suggests that good research practices should include “a variety of numerical and graphical summaries” of data when interpreting the results of research [26]. As mentioned prior, there was no statistical difference between the HC and LC anxiety levels either during a practice or game like scenario. However, 0% of the LC position players expressed high anxiety prior to a practice or scrimmage whilst 20% of HC of the position players expressed high anxiety prior to a practice and/or scrimmage. From a pragmatic stand point, this information has tremendous value for a coach. Knowing that HC position players may have a greater propensity for high anxiety prior to practice or games can allow the coach to take preemptive actions to help reduce anxiety.

5. Conclusions

- Within the parameters of this study, there was no statistical difference between anxiety levels in:• HC vs. LC players prior to practice,• HC vs. LC players prior to a scrimmage,• OFF vs. DF players prior to practice,• OFF vs. DF players prior to a scrimmage,• OFF players prior to practice vs. prior to a scrimmage, and• DF players prior to practice vs. prior to a scrimmage.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML