-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2018; 8(1): 38-42

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20180801.06

The Effect of Practice in Mind (PIM) Training on Jumping Performance of High Jumpers

Afifah Azizan , Mazlan Ismail

Faculty of Sports Science and Recreation, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Afifah Azizan , Faculty of Sports Science and Recreation, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Imagery is defined as an experience that are created or recreated within the mind by using different sensory modalities such as kinesthetic, visual and auditory imagery which play an important role in Psychological Skills Training. Consequently, Practice in Mind (PIM) training is an appropriate combination of skill practices and imagery training technique program design in order to achieve the desired training goals. Therefore, this study attempted to investigate the effect of PIM training on jumping performance of high jumpers. A double-blind experimental design research was conducted to twenty-six high jumpers (n =26) aged between 13 to 17 years old. Participants were randomly assigned into two different groups (PIM group and control group) with 13 participants for each group. Both groups completed 18 training sessions three times per week in a six-week intervention program. The results showed that PIM group had significantly performed better in jumping performance compared to control groups. The finding supports the idea of using PIM training to improve sports skills performance. Additionally, high jumpers should not focus on their skills training only to be successful but also develop their psychology training particularly in imagery training.

Keywords: PIM Training Program, Imagery Training, Skill Practice, High Jumpers

Cite this paper: Afifah Azizan , Mazlan Ismail , The Effect of Practice in Mind (PIM) Training on Jumping Performance of High Jumpers, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2018, pp. 38-42. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20180801.06.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Nowadays during competition, society has an extremely lofty expectation towards performance of the athletes as a primary focus rather than the skill and abilities of the athletes and the reason of the participation of the athletes, without realizing its consequences which loads a high stress and may affect the performance level of the competitors [1]. Consequently, there will be a distraction in self-confidence of the athletes who are unable to cope with such demands because they need to fulfil the expectation of the audience during the game. Previous researchers explained that some coaches ignored the need of having mental skills training during their daily schedule with athletes and consequently their athletes were not mentally well prepared and fail to focus during competition [2]. Furthermore, Xiong has stated that the role of psychological factor has become more prominent in determining the result of the competition [3]. Therefore, in accordance to balance the situation to make the athletes perform at their peak point, there are several individual psychological factors that may affect their potential performance which are motivation, visualization, psychosomatic skills confidence and attention, which may be applied to athletes training program by coaches, sport psychologist and sport scientist [4]. Previous researchers indicated that Psychological Skill Training (PST) may improve athletes’ performance by increasing enjoyment, and self-satisfaction in doing physical activity which proves to be an effective strategy to generate exceptional performance in various sports by enhancing performance [2, 5-7]. The importance of Psychological Skill Training (PST) has been acknowledged frequently by athletes, coaches and sport psychologists as one of the tools in enhancing athletic performance [8]. Some of the examples are goal setting, emotional control, attentional control, imagery, self-talk and relaxation [9-12]. Previous studies also found that imagery is one of the most widely-used techniques in the sports arena and one of the most documented in sport psychology [6, 5, 13, 14]. However, Morris et al. stated that there are several factors that may influence the effectiveness of imagery program on individual performance [6]. For instance, imagery direction (i.e., facilitative and debilitative) may help in enhancing athletes’ performance. In order to have an effective imagery in sport, imagery perspectives and modality are important considerations [6, 15-17]. Therefore, the most crucial sensory modality which can differentiate between imagery is visual and kinesthetic, hence it should be considered so that it would lead to discrete information [15]. For maximum effectiveness of imagery, Morris et al. have concluded that the combination of perspectives and modalities are fundamental in allowing athletes to gain as much information as possible so they may have an idea of a movement that they have to do [6]. Imagery is one of the interventions that can be delivered using various methods or technical aids. For example, written scripts, video-and audio-tape can increase performance of athletes [5, 18-21]. As Smith and Holmes (2004) has revealed that video and audio groups achieved superior performance rather than written script and control groups (i.e. reading golf literature) on golf putting performance [22]. Recent studies conducted by Mazlan (2014, 2015, 2016a, 2016b) found that Practice in Mind (PIM) training program improves sports skills performance [5, 19, 20, 21]. PIM training program is a complete and systematic 6 weeks, 3 times a week program of imagery training and explores all seven PETTLEP imagery components created by Holmes and Collins (2001) [23]. It is paired together with ten mental practices and ten skill practices in one training session on the same day. Previous studies showed that PIM training program helps to improve individual sports like golf [5, 19-21]. Furthermore, it was also effective in team sport like rugby [24] and Netball [25, 26]. In high jump, the idea is athletes need to jump over the bar and land in the pit without knocking the bar to fall over. According to Dapena, high jump can be divided to three parts: run-up phase, take-off phase and the flight or bar clearance phase [27]. However, most of the problems faced by the athletes who failed for bar clearance were actually at take-off phases which need the power of leg to exert forces for maximum height while making the jumping. This is because the vertical velocity of the athlete at the end of the takeoff phase determines the highest peak that will reach after the athlete leaves the ground, which was one of the great importance’s for the result of the jump [27]. In improving the sport performance, imagery training has been extensively used in athletes [28] and there was a need to be systematically practiced. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the practical application of PIM training program on high jumper performance. Since the effectiveness of the PIM training obtained and the conclusions drawn cannot be taken to represent all athletes, especially in athletics.

2. Methodology

- Twenty-six district level male high jumpers aged between 13 to 17 years’ old, (M= 15.5, SD= 1.15) participated in this study.

2.1. Instrumentation

- Vertical Jump. The movement during take-off phase component can be assessed using the vertical jump as the test implies a more representative movement of the take-off phase in high jump execution. Each attempt of the jumping performance (vertical jump) was recorded and classified according to the norms category for vertical jump (Patterson & Peterson, 2004) [3]. The internal reliability of the vertical jump norm by Patterson & Peterson was reported with .74.

2.2. Procedure

- For the purpose of this study, the participants were assigned (fishbowl method) into two groups; (1) PIM group (combined imagery – skill practice) and (2) control group (only skill practice) right after imagery ability assessment. The imagery ability of the participants were 16 and above in this study (as measured by Movement Imagery Questionnaire-Revised, Hall & Martin, 1997) [31]. The training program was introduced to all participants’ right after the pretest. The participants in PIM training read the script about vertical jump and recorded it using a voice recorder. Then, participants were asked to listen to the voice recorder which consists of the imagery guide and 10 mentally performed highest vertical jumps. They were not allowed to do any actual movement while performing the imagery practice [5]. One of the PETTLEP components in this study is like wearing proper competition attire (Physical Components). Furthermore, they need to imagine the full routine, cognitively and kinesthetically with stimulus and response prepositions for the highest jump (from walking to the highest vertical jump) at the correct pace (Emotions and Timing components). The Vertec will be put at the rubberized track (Environment component). Subsequently ‘Task’ component in term of thought is described as imagined task which is the same as actual task like feelings and actions take place. Next, the participants listened to their own imagery scripts from the voice recorder (Perspective component). Additionally, the participants were advised to make some changes to the general script every session of imagery practices. The duration for every session was 15 minutes for each athlete (5 minutes for 10 imagery practices and 5 minutes for 10 attempts of vertical jump). Warming up and cooling down sessions were about 5-7 minutes each. Moreover, 10 vertical jumps were performed by the participants in the control group and the session conducted by the coaches. They were asked to record all the training progress in a diary given and were monitored by the researcher after each session.

3. Results

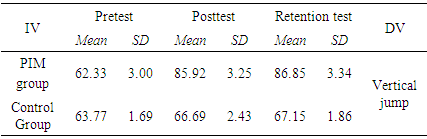

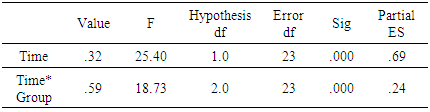

- Table 1 shows means scores of jumping performance in Vertical Jump test from pretest, posttest and retention test between PIM training (combined imagery – skill practice) and control group (only skill practice). It can be concluded that the means of height of the vertical jump performance of PIM training largely increased from pretest to posttest (M= 62.23 SD= 3.00 to M= 85.91, SD = 3.25) and slightly increased from posttest to retention test (M= 86.85, SD= 3.34). Additionally, means of height of vertical jump performance of control group slightly increased from pretest, posttest and retention test (M= 63.77, SD= 1.69 to M=66.69, SD = 2.43 and M= 67.15, SD= 1.86).

|

|

4. Discussion

- The present results showed that there was a significant difference between groups (PIM group and control group) jumping performance of high jumpers. In fact, there was a superior improvement in jumping performance across the three time periods with the PIM group showing an increment scores from pretest to posttest higher than the control group. Additionally, the results of the retention tests for the PIM training group showed that jumping performance effect can be maintained. It can be suggested that the PIM training which combining skill practice and imagery training produced a great improvement in jumping performance for high jumpers. As Olsson et al. reported that the high jumper performance had showed an increment on their improvement after completing the physical training program with combination of visual imagery [34]. It is clearly supported by the previous findings that by combining the physical and imagery practices had improved sports skill performances compared to control group [5, 19-21, 24, 33]. The combination of the skill practices and imagery training claimed that skill practices alone without imagery intervention was not found to be significantly efficient to enhance motor skill performance [5, 18]. As supported by previous studies the use of audio technical aid in imagery practice was significantly elevated by a bout of jumping performance to PIM training group compared to control group (only skill practice) because the audio provides a similar perspective as script reading [22, 23]. Most probably, the positive vibe in emotional state helps the athletes to enhance their sport skills especially in jumping performance [5, 22, 24]. Moreover, the 6 weeks intervention can be successful in helping athletes to learn psychological skill as their intervention while practicing skills in sport [4]. The present study showed that there was a statistically significant increase of the result and increment of height of vertical jump after 6 weeks of training sessions [34, 35].

5. Conclusions

- The present study opens up several suggestion and recommendation for future research to further examine those areas of concern in details. The results cannot be taken to represent female athletes, since the sample of this study is limited to male high jumpers. Other than psychological factors, it would be interesting for future study to combine PIM training and skills analysis like knee kinematics or flexion of the knees while jumping. It may enhance further understanding about PIM training in changing the body movement and how it affects the performance indicator.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to thank Majlis Sukan Negeri Kedah Malaysia and participants for the support and cooperation in completing this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML