-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2017; 7(6): 227-232

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20170706.04

Utilization of Sports and Games for Psychosocial Rehabilitation of Internally Displaced Persons in Maiduguri, Nigeria

Stephen S. Hamafyelto, Hussaini Garba, Mary Pindar Ndahi

Dept. of Physical & Health Education, University of Maiduguri, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Stephen S. Hamafyelto, Dept. of Physical & Health Education, University of Maiduguri, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

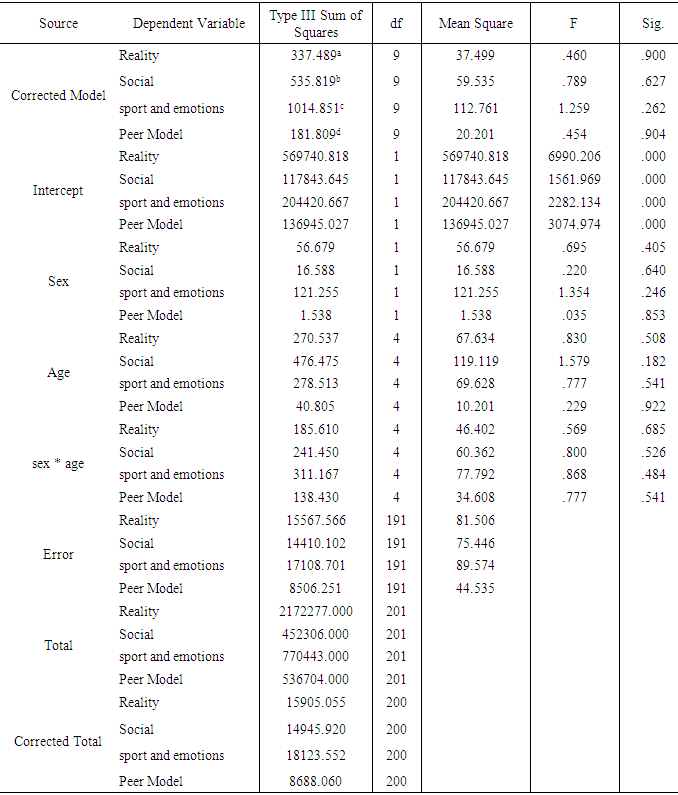

The study was carried out with the intent to mitigate the trauma experienced by victims of insurgent attacks by the so called Boko Haram militants in Borno state of Nigeria. The area was ridden by the crisis over the past 9 years. As a result, many people were killed, maimed and raped. Some others suffered all manner of inhuman treatment in the hands of their captors. The extent to which this dehumanized treatment has impacted on the people in this area has left most of them traumatised. Victims who survived the attacks have been resettled in government managed camps where their needs have been addressed. Many interventions have also been provided by government, non-governmental organisations and corporate and individual bodies. In this regard, social needs of the victims have been the immediate concerns of most organisations, where food, shelter and clothing were provided. However, there is little that has been done to rehabilitate these victims psychosocially. In this regard, sports and games including the victims’ local games were used to provide psychosocial rehabilitation of victims. The intent was to bring them back to social reality, social inclusion, and stable emotions and peer integration. Descriptive statistics and Multivariate analysis was done. No statistical significant difference was found among male and female children and adults in terms of psychosocial rehabilitation using sports.

Keywords: Social Reality, Social Inclusion, Peer model

Cite this paper: Stephen S. Hamafyelto, Hussaini Garba, Mary Pindar Ndahi, Utilization of Sports and Games for Psychosocial Rehabilitation of Internally Displaced Persons in Maiduguri, Nigeria, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 7 No. 6, 2017, pp. 227-232. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20170706.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

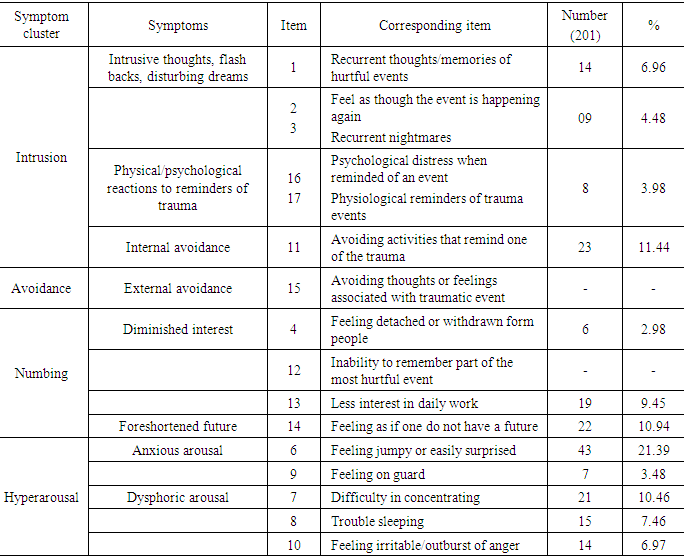

- Sports and games have been found to be useful tools in rehabilitation of injured athletes in literature and many studies have also shown the significant role psychosocial rehabilitation plays in bringing athletes back to their feet after injuries. Rehabilitation of athletes is being considered as a multi-faceted process involving not only the surgeons, physiotherapists, coaches and other sport scientists. Substantial progress has been made in rehabilitation of injured athletes over the years, with psychosocial support being consistently advocated by experts. Early studies have also shown that psychosocial interventions positively influence athletes’ injury recovery, promotes personal recovery, successful community integration and satisfactory quality of life. Indeed, rehabilitation aims to facilitate recovery from loss of function. In this regard, loss may be due to physical conditions such as fractures, amputation, stroke or neurologic disorders among many other conditions.Researcher have shown that survivors of disaster are usually left alone and forgotten until there is increased news outlet attention given to them so that people come to their aid most times. For the community, sport can mean that safe spaces are established for individual and communal healing (Engelhardt, 2013).According to UNESCO (2017), while there are no official definitions of an internally displaced person, the organisation asserts that internally displaced persons are "persons or groups of persons who have been forced to flee, or leave, their homes or places of habitual residence as a result of armed conflict, internal strife, and habitual violations of human rights, as well as natural or man-made disasters involving one or more of these elements, and who have not crossed an internationally recognised state border."Using sport and games in psychosocial rehabilitation of internally displaced persons (IDPs) is indeed not new. Situations such as armed violence, terrorism, flood, earthquakes, have been known to cause mass movement of people from their original place of habitations. Organisations such as International Committee of the Red Cross have used sports to help rehabilitate victims of war and armed violence as a humanitarian response to the needs of the victims. International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC) (2016) noted that sport is key tool in promoting social inclusion for people with disabilities because it changes the perception of the community about them. Besides rehabilitation of victims the use of sport to promote peace and development seem not to be entirely new for example, the Olympic movement remains the strongest medium for promoting global peace.Anecdotal evidence have shown that sport promotes social cohesion, social inclusion, shared social reality, emotional support, emotional challenge, motivation and use of peer model as part of psychosocial rehabilitation of victims of disaster resulting from armed conflicts, terrorism and civil disturbance across the globe ( Power, David & Kless, 2009). The purpose of this paper was to examine the effectiveness of sports and games in rehabilitating victims of terror and insurgency in the Northeast on Nigeria.Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)The incidence of gruesome murder, maiming, rape, food deprivation and hunger that victims experienced in the course of the insurgency has remained indelible in their memory. Most of the victims interviewed in this study loss their fathers in the mayhem. Absent living fathers is common and increasing phenomenon affecting families in Africa (Department of Social Development, 2012). This has caused inability of the families’ resilience which indeed has consequences in social cohesion, social integration and social reality by adults and children. Dysfunctional families in which conflict, misbehavior, neglect or abuse occurs have the ability to suffer depression and psychosocial disorientation. While some witnessed loss of father some experienced and witnessed the rape of their sisters and mothers. Power, David and Kless (2009) defines PTSD as disorder that develops in some people who have experienced a shocking, scary, or dangerous event. Meier (2005) in a study of gender asserts that sports and games may be able to alleviate symptoms of PTSD and improve mood and confidence. In additions, sports and games may help build self-confidence, self-discipline, body awareness, and teamwork and communication skills.In a study on High-intensity sports for posttraumatic stress disorder and depression…Rogers, Mallison and Peppers (2014) concludes that participants reported meaningful clinical improvement in PTSD symptoms after applying intervention training programme on the victims of PTSD. Group of veterans similarly indicated significant decreases in PTSD symptoms and increases in marital satisfaction among the experimental groups following participation in recreation program. Findings support the use of recreation programs to help veterans with PTSD and their significant others, through specific program elements (Bennett, Lundberg, Zabriskie, & Eggett, 2014).Sport and shared social realityThe Psychology Dictionary defines social reality as the attitudes, beliefs and opinions that are held by members of a society or a group. Apparently, the social reality of a group deals with their opinions and beliefs as such these constitute a people’s set of social judgments that the members of the group agree upon. Green (1998) defines sport as a physical activity which is fair (fair meaning honest in that the contest structured for all contestants to have a reasonable chance to win), competitive, non-deviant, and is guided by rules organisations/traditions. The theoretical concept of social reality has been extensively supported by researchers (Searle, 1995; Smith & Searle, 2003). Gale (2008) explains that games are examples of social constructed entities and often exist because of certain sets of conventional rules. As such these set of conventions and agreement to abide by them give games their meaning in any given social context.Sport and social inclusionIn United Kingdom, for instance, sport has been recognised as a means for promoting social inclusion (Liu, (2009). There are research evidence that explains sport and social exclusions, segregations, racism, poverty and social inequalities, ethnic discrimination, disabilities and gender differences. Marivoet (2014) suggests that there is broad consensus at institutional level on the notion of social inclusion in sport and inclusion through sport. According to Marivoet, social inclusion means the actual existence of equal opportunities in accessing sports. Therefore good practices are seen as the promotion of wide spread sports and the presence of people that tend to be excluded in a society from participating in sports.In a study by McConkey, Dowling, Hassan and Menke (2012) it was found that with social inclusion there is increase in bond development between athletes and partners, teamwork, friendship and respect for one another is enhanced. Kelly (2011) investigated the social inclusion with specific reference to four main themes; sports for all, social cohesion, path way to work and giving voice. Varying degree of successes was recorded by the programmes. However, their impact on social exclusivism was evidently limited.Sport and emotionSport and games have been noted as means of generating strong emotional responses among participants and spectators alike. Deci (2008) in Hanin (2012) defines emotion as a reaction to stimulus event (either actual or imagined). Darko (2016) posits that there are many cognitive models that try to explain why people are more physically active than others. These models say that one is physically active if the perceived benefits for example, health is higher than the cost (time or money) invested. It therefore means that the desire to engage in sport, games and recreation depends upon the comparative advantage the individual appraises. In this regard, task-involvement may be positively related to challenge appraisal, which is defined as a “focus on the potential for gain or growth inherent in an encounter” (Lazarus, & Folkman, 1984). Task-involved individuals may view sport competition as an opportunity to improve their performance, gain experience and competence as such they appraise it as challenge.Peer modelSeveral studies in sport have indicated that peers are a significant contributor along adults in creating a motivational climate in sport (Hamafyelto & Badejo, 2002; Hamafyelto & Ajayi, 2002; Cervello, Escarti, & Guzman, (2007). In the study by Cervello et al for instance, significant others were found to be influential in the dropout syndrome and that task orientation is indeed positively related with motivation, affective, behavioural patterns than ego-orientation. Some studies have investigated the difference between persistence and dropout among young athletes. Both friendship and peer acceptance have been examined in conjunction with motivation-related variable in youth sport research (Smith, Ullrich-French, Walker II & Hurley, 2006). Positive friendship quality and more adaptive peer relationship profiles and more adaptive motivation-related responses were observed among the young athletes. Results showed that more positive perceptions of social relationships were associated with more positive motivational outcomes.

2. Methodology

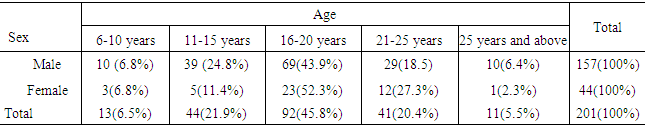

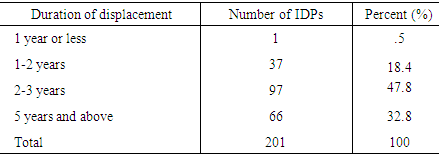

- The aim of this study was to examine the utilization of sports and games in providing psycho-social rehabilitation of victims of insurgency and terrorism in Northeastern Nigeria. These victims had suffered from Posttraumatic Stress Disorders due to various conditions experienced during the attack of their villages and towns. The period of training took eight (8) weeks. Respondents assemble in their play area at 3.30 pm where role call is made by the research assistants and pep-talks to assure them of the need to engage in sport/games.SampleThe participants of the study were two hundred and one (201) youths placed in the Internally Displaces Peoples (IDPs) camps. These are homeless people affected by the insurgency and terrorism in this part of the country. Of these number, 158 were males while 43 were females; aged between 6 and 19 years (Mean age= I8.58 years, SD = 1.24).ProceduresThe researchers obtained permission from the authorities to be able to enter the camps and sample respondents for this study. Participants were assured that engaging in sports and games will have no any negative effect on their physical, mental, social and moral conduct. They could withdraw at any level if they feel exhausted and would not want to continue. Upon obtaining permission and ethical approval by the regulatory bodies, the researchers sampled the two hundred and one (201) IDPs that volunteered to participate in the study. They indicated their sport and game of choice and agreed to participate in the games as scheduled by the researchers.The youths who volunteered to participate were given consent forms to fill and return through an interpreter research assistant. There were 43 (27.2%) football players, 14 (9.1%) volleyball players, 20 (12.7%), table tennis players were 20 (12.7%) and 11 (7.0%) snooker players. Traditional games: there were 23 (15%) boys in traditional wrestling (dambe), while 7 (4%) went for draft game and 20 (13%) were engaged in langa (one-leg race). Of the 43 female participants, 12 (28%) were engaged in playing an instrument known as Jento while 9 (21%) were engaged in playing cards and ludo games. Skipping and racing had 22 (51%) females engaging in various forms of unorganized sports; skipping, sac race, and sharapke (pebble catching).

3. Results and Analysis

|

|

|

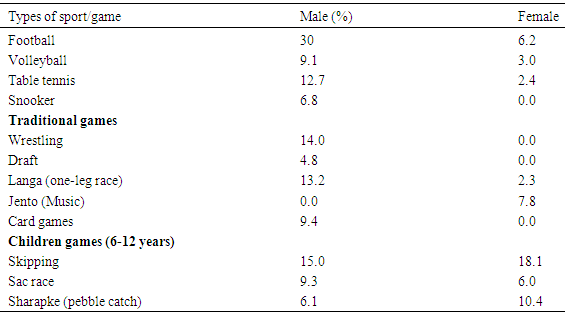

The distribution of sport and games showed that 30% of the males and 6.2% of the female respondents participated in football. In Children games, 18.1% female and 15% male children participated in skipping. Pebble throwing and catching had 10.4% female who participated in it. Some the respondents participated in more than one sport/game during the study.

The distribution of sport and games showed that 30% of the males and 6.2% of the female respondents participated in football. In Children games, 18.1% female and 15% male children participated in skipping. Pebble throwing and catching had 10.4% female who participated in it. Some the respondents participated in more than one sport/game during the study.

|

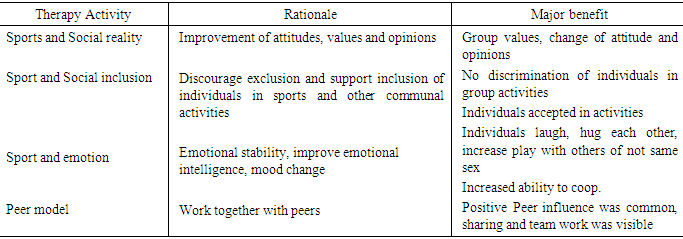

4. Discussion

- The study was designed to utilize sports in rehabilitating the Internally Displaced Persons in Maiduguri, Borno state. This area was badly hit by the conflict of the Boko Haram insurgency. The insurgency has crippled the total social, economic, educational and personal platform of the region. This has resulted in the efforts of the Government of Nigeria, Non-governmental Organisations, and Corporate Organisations to ensure that the suffering of victims is mitigated to the barest minimum.It became necessary to use sports and games to rehabilitate those victims of the insurgency in this regard. The psychosocial rehabilitation focused primarily on social reality, social inclusion, emotions and peer model. Four separate questionnaire forms were administered to the victims who all accepted to participate in the study.From the results it is evident that male and female victims showed that they were traumatised by the insurgency. Nasty activities including killing of family members, rape, maiming and denial of food and other form of labour charactised the insurgency. As noted (Department of Social Development, 2012) the loss of family member especially the bread-winner of the family like a father is devastating and unbearable in every circumstance. Apart from loss of father, incidence of rape and maiming has thrown most children into trauma that can be hardly forgotten. Sports has provided avenue for children and adults to play, relax, socialise and work in teams including improving physical capacity and mental alertness and emotional balance.

5. Conclusions/Recommendations

- Base on the findings in this study it is concluded that sports and games have influence on psychosocial rehabilitation of victims of insurgency in Borno state. They have demonstrated stable social reality, social inclusion, stable emotions and good peer relations with mates. We therefore recommend that sports like basketball, football, table tennis, volleyball and local games should be widely popularized in secondary schools to help increase the skill levels of the students and pupils.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML