-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2017; 7(5): 177-183

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20170705.01

Effect of Opponent Quality on Goal-patterns from Direct Play in Japanese Professional Soccer

Taiki Miyazawa1, Maki Keika2, John Patrick Sheahan3, Daisuke Ichikawa4

1Faculty of Wellness, Shigakkan University, Obu, Japan

2Graduate School of Medicine, Fujita Health University, Toyoake, Japan

3Institute of Sport Science, Yamanashi Gakuin University, Kofu, Japan

4Department of Biomedical Engineering, Toyo University, Kawagoe, Japan

Correspondence to: Taiki Miyazawa, Faculty of Wellness, Shigakkan University, Obu, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The quality of the opponent is considered an important factor that can influence attacking performance in soccer. Despite this, it is unknown whether the quality of the opponent has an influence on the effectiveness of direct attack goal scoring and its characteristics. The aim of this study was to determine the influence of league ranking which is one of opponent quality on the percentage of goals scored by direct attack of all goals based on the analysis of Japanese professional soccer league (J-League) in 2016. We also validated the effect of opponent quality on the characteristics of direct attack. In order to accomplish this aim, all goals from open play were divided into two categories based on league-table position at the end of season of the team from which the goal was scored: goals scored against inferior position teams (IN-goals) and superior position teams (SU-goals). Furthermore, these goals were divided into two attacking styles: direct and elaborate attack. For the comparison of characteristics of direct attack, further analysis was conducted on three variables toward goals scored by direct attack: passes per possession, possession duration and possession starting zone. The number and percentage of goals scored by direct attack in IN-goals was 130 goals and 37.6% and significantly lower than those in SU-goals (89 goals and 46.8%). There was no difference in distribution of the characteristics between IN- and SU-goals. Our findings suggest that effectiveness of direct attack for goal scoring become higher against superior opponent quality. In contrast, the characteristics of direct attack were not affected by opponent quality. Direct attack with two passes, duration of 10 seconds or less and starting at the offensive half is thought to be common among the goal scoring against superior and inferior opponents in order to improve goal scoring ability.

Keywords: Direct play, J-league, Attacking style, Elaborate attack, Pass number

Cite this paper: Taiki Miyazawa, Maki Keika, John Patrick Sheahan, Daisuke Ichikawa, Effect of Opponent Quality on Goal-patterns from Direct Play in Japanese Professional Soccer, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 7 No. 5, 2017, pp. 177-183. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20170705.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Match performance in soccer is influenced by strategies defined as the overall plan that is devised and adopted to achieve an aim or specific objective [1]. Attacking style is an especially important factor that is directly linked to success. Many studies suggest that goal scoring and ball possession characteristics such as number of passes and possession duration are the ultimate measure of attacking effectiveness in soccer and has subsequently received considerable attention in match-performance analysis [2-5]. The information from these studies of tactics are of value in contributing to more tactical knowledge for the prescription of specific exercises within the training regimen and for analysing match performance [6].The attacking styles in open play fall into two main categories: direct attack and elaborate attack [3, 4, 7-12]. Direct attack is linked to counter-attacking and fast attack methods of attacking play. Elaborate attack is a style linked to positional attacking method. So, there are three methods of attacking play. The Direct attack is defined as trying to move the ball into a shooting position as quickly and directly as possible with the least number of passes [3] and is often equated with counter-attacking [4, 9]. In contrast, the Elaborate attack is defined as having more ball possession (longer ball possession periods, more passes per possession) than the respective opponent, playing risky passes preferably in the attacking third; hence elaborate attack or possession attacks, respectively, “often progress relatively slowly” [9, 13]. The quality of opponent is an important factor that can affect teams’ performance [14-16]. The analysis of the effectiveness of attacking styles must consider the interactions between the two opposing teams. Indeed, it is well known that elite teams tend to base their competitive success on strategies that emphasize the maintenance of ball possession [17, 18]. Furthermore, several studies identified longer ball possession durations to be linked to successful teams [5, 19]. These findings imply that the time of ball possession tends to be shorter when the opponent is superior to one’s own team. Thus, it is thought that direct attack might be a more effective attacking style than elaborate attack for goal scoring and success against superior opponents. It is also presumed that the starting position of direct attack might be farther from goal when the opponent quality is higher because the opponent possesses and brings the ball forward over a longer duration. However, it is unknown whether the quality of the opponent influences effectiveness of direct attack for goal scoring and its characteristics in soccer.In this context, the aim of this study was to determine the influence of opponent quality represented by league ranking on the percentage of goals scored by direct attack to all goals in open play based on the analysis of the games of Japanese professional soccer league (J-league) in 2016. We hypothesized that goals scored against superior opponent have higher dependence on direct attack compared to elaborate attack. For the attainment of the aim, we divided the all goals from open play into two groups based on the team’s league table position; goals scored against lower ranked teams and higher ranked teams. The percentage of direct attack and elaborate attack were compared between groups and we hypothesized that the characteristics of direct attack such as number of passes, duration and starting zone was influenced by opponent quality. Therefore, we also compared the characteristics of direct attack between the goals against superior and inferior team.

2. Methods

2.1. Materials

- A sample of 536 goals scored from open play collected from 805 available goals scored in total in the Japan top professional league (J-League) in 2016 season were analysed by viewing videotapes recorded from live TV broadcasts. The league involved 18 teams played in a double round robin competition format, which means that each team played 34 matches, 17 home and 17 away.

2.2. Procedure

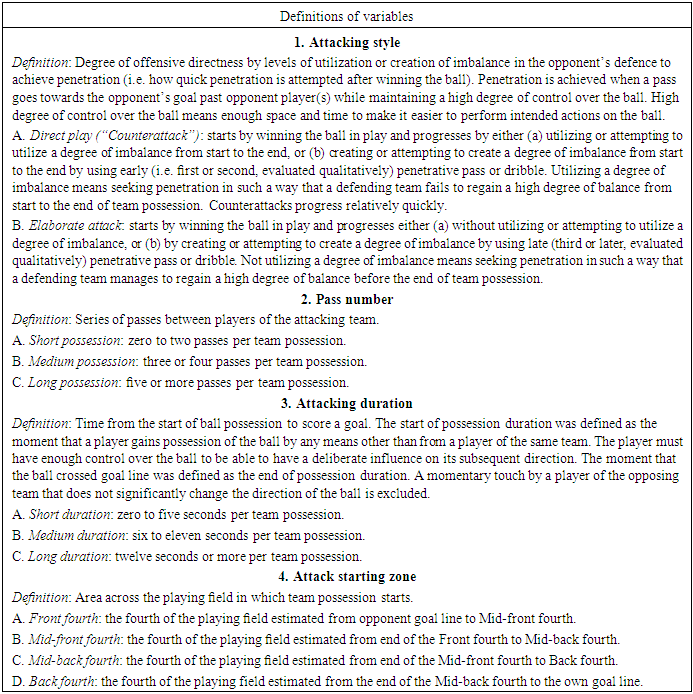

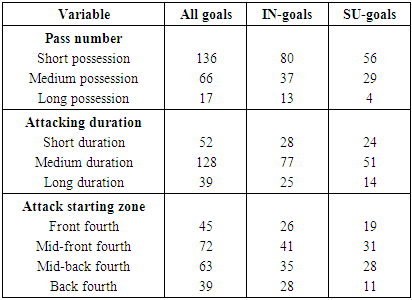

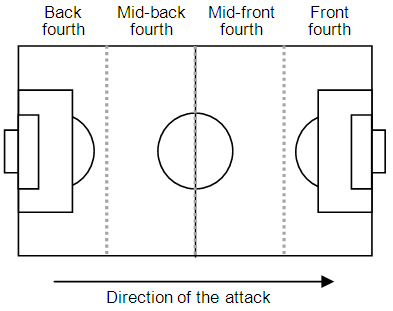

- All goals were divided into two groups based on league-table position at the end of season: goals scored against inferior position teams (IN-goals) and superior position teams (SU-goals). For example, in the case of 8th team, the goals scored against 9-18th teams were classified into IN-goals and the goals scored against 1-7th teams were classified into SU-goals.The goals were then divided two attacking styles. One was direct attack, which was defined as possession with a high degree of offensive directness that attacks the opponent’s goal directly by using forward passes and dribbles immediately after possession of the ball has been won. In contrast, the second style of attack was elaborate attack, which was defined as possession with a low degree of offensive directness with a low risk of losing the ball often through the use of safe passing and dribbling either backwards or sideways [20]. We divided the goals into two attacking styles: direct attack or elaborate attack using the definitions shown in Table 1, which were determined by reference to the previous study [9]. A team possession was used as the basic unit of analysis and was defined according to Pollard and Reep (1997) [21]: “A team possession starts when a player gains possession of the ball by any means other than from a player of the same team. The player must have enough control over the ball to be able to have a deliberate influence on its subsequent direction. The team possession may continue with a series of passes between players of the same team but ends immediately when a goal is scored by a team in possession of the ball. A momentary touch by a player of the opposing team that does not significantly change the direction of the ball is excluded.”For the purpose of comparing characteristics of direct attack further analysis was conducted on three variables toward goals scored by direct attack: number of passes per possession, possession duration, and possession starting zone. These variables and their reliability results are presented elsewhere [9]. Passes per possession was the number of passes after regaining the ball from the opponent used until scoring the goal. Time from the start of ball possession to score a goal. Possession duration was defined as the time from the start of ball possession to score a goal. The start of possession duration was defined as the moment that a player gains possession of the ball by any means other than from a player of the same team. The player must have enough control over the ball to be able to have a deliberate influence on its subsequent direction. The moment that the ball crossed goal line was defined as the end of possession duration. For the analysis of possession starting zone, the pitch was divided into four zones parallel to the goal lines. These were labelled Front fourth, Mid-front fourth, Mid-back fourth and Back-fourth (Figure 1). The position of regaining the ball and starting the direct attack was analysed with reference to grass lines and pitch lines and was labelled as the possession starting zone. The definitions used to perform the analysis were determined by reference to the previous study [9] and shown in Table 1.

|

| Figure 1. Pitch divisions in four zones parallel to the goal lines |

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- All statistical analysis was performed using StatFlex, version 6.0 for windows (Artech Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). The level of significance was set at p<0.05. The null hypothesis, predicting that there would be no difference in how goals are scored between IN- and SU-goals, was tested by the χ2 test. The χ2 test was also conducted to analyse difference in total goal number, percentage of each attacking style and characteristics of direct attack between IN- and SU-goals. For the comparison of mean pass number and attacking duration between IN- and SU-goals, student’s t-test was used.

3. Results

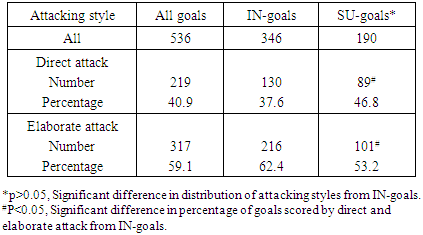

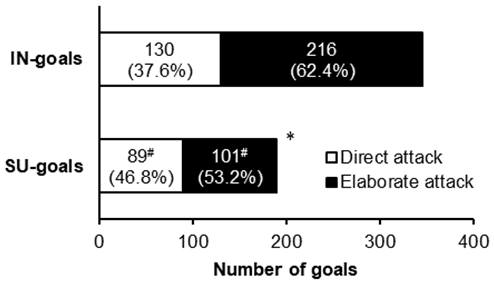

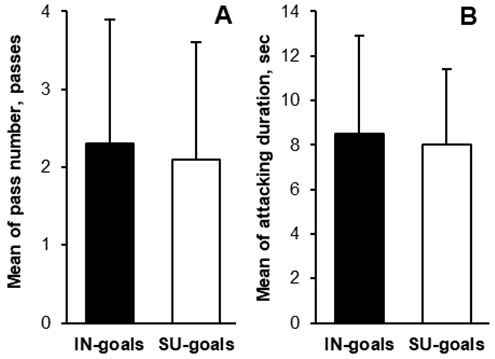

- 536 goals were scored in total. The number of goals scored from each attacking style was 219 (40.9%) in direct attack and 317 (59.1%) in elaborate attack. IN-goals scored against lower position teams were 346 (64.6%) and significantly higher ratio than the SU-goals 190 (35.4%) scored against upper position teams (P<0.05). In a comparison of IN- and SU- goals (Table 2 and Figure 2), the number of all SU-goals (190 goals) was significantly lower (P<0.05) than that of all IN-goals (346 goals). The number and percentage of goals scored by direct attack in IN-goals was 130 goals and 37.6% respectively, which was significantly lower than those in SU-goals (89 goals and 46.8% respectively). Conversely, the number and percentage of goals scored by elaborate attack was significantly decreased (P<0.05) from 216 goals and 62.4% respectively in IN-goals to 101 goals and 53.2% respectively in SU-goals. These changes in distribution of goal numbers between IN- and SU- goals were statistically significant (P<0.05).

|

| Figure 3. Comparison of mean pass number (A) and attacking duration (B) between IN- and SU-goals |

|

4. Discussion

- The objective of the present study was to determine the influence of opponent quality on the configuration of attacking styles of play in the Japanese professional soccer league. We focused the investigation on whether the effectiveness of direct attack for goal scoring was affected by opponent quality. The number of goals scored from teams with a superior ranking at the end of the season was significantly lower than goals scored from the teams with an inferior rank. In the goals scored in open play, the percentage of goals scored from direct attack was increased from 37.6% against inferior teams to 46.8% against superior teams. This suggests that the effectiveness of direct attack for goal scoring was influenced by the quality of the opponent. This indicates that direct attack was a more effective goal scoring method against higher quality teams. For a goal to be scored in soccer a team must have possession of the ball. Thus, it might be anticipated that longer periods of possession would increase goal scoring potential [6]. For example, it is presumable that the higher number of possessions a team has the greater the chance they have of entering the attacking third of the field and consequently more goal scoring opportunities created [6]. In fact, previous studies have reported that successful teams maintained possession for longer than unsuccessful teams [2, 3]. Several studies supported these findings and identified longer ball possession duration to be linked to successful teams [5, 19]. In actual training of soccer in Japan, coaching aimed to maintain possession like Spanish soccer teams and F.C. Barcelona’s style seemed to become mainstream. However, attacking performance in soccer is a complex process influenced by several situational variables [22]. In this respect, the behaviours of the players and teams involved in attacking patterns of play seem to strongly depend on the type of competition [23], game location, i.e. home/away factor [6, 24], opponent quality [6, 16] and match status, i.e., when the teams are winning, losing or drawing [25]. Similarly, several studies demonstrated that ball possession was influenced by variables such as match status [5, 17-19, 22] and the quality of the respective opposing team [17, 19, 26]. Therefore, elaborate attack is not necessarily effective for goal scoring. Regaining possession occurs whenever a defender acts on the ball (or zone of the ball) in order to recover it from the opponent, which then initiates attacking behaviours [27]. Additionally, regaining possession in a dynamic way occurs due to an error of the ball carrier or by a defender intervention [28]. Against high quality opponent it seemed to be difficult to regain the ball and possess it for long durations because of the opponent’s high defensive skills. In fact, several studies [6, 17] have pointed out that attacking durations tend to be shorter when the opponent is top-level. Therefore, if the opponent quality is high, it is thought that teams decrease their possession, suggesting they preferred to play counterattacking or direct attack (that is, move the ball quickly to within scoring range, often using long passes or long balls downfield). In the present study, we compared the contribution of direct attack and elaborate attack in goal scoring from open play between the goals from superior and inferior ranked teams and determined that the contribution of goals from direct attack was higher in the goals against superior teams than those against inferior teams. These results suggested that the changes in tactics and the style of play adopted by teams from elaborate attack to direct attack according to the opponent quality might be effective for goal scoring.In the present study, the percentage of goals from elaborate attack constituted more than half of goals scored by open play in both IN- and SU- goals with little influence from the quality of the opponent. More than 60% of IN-goals were scored from elaborate attack. This result suggested that elaborate attack was effective for goal scoring and became more important against inferior teams. The distribution of goals scored in closed play including free kicks and corner kicks was increased from IN- to SU- goals with a decrease in goals from elaborate attack. Although direct attack became effective with the change in opponent quality in view of only the comparison among open play, it was suggested that the goals from closed play become important attacking avenue for goal scoring against superior rank teams in view of overall goals. It was considered to be more difficult to put the goal away in open play against superior rank teams because of their high ability to recover the ball, which leads to a corresponding lower duration of ball possession [27]. Corner kicks and free kicks make it possible to supply the ball in the immediate area of the goal with just one pass. Depending on the quality of the pass or the ability of the shooter positioned in front of the goal, set plays including corner kicks and free kicks represent a huge opportunity for goal scoring. In this instance, passes, dribbles and challenges with opponent were kept to a minimum. Therefore, it seemed that the influence of the opponent quality in closed play might be lower than that in open play. Regardless of opponent quality, closed play can be a chance for goal scoring on a constant basis and a great deal of time should be spent it in common training. Attacking characteristics such as number of passes [3, 4, 29], duration [3-5, 17, 19, 20, 29] and starting zone [4, 11, 28-30] have been reported to influence match performance including goal scoring. For example, possessions with longer passing sequences were previously found to be more effective in goal scoring than those with shorter passing sequences [3, 4]. Further univariate and multivariate analyses have shown that long possessions were more effective than short possessions when playing against an imbalanced defence, but not against a balanced defence. It would appear that a relatively high number of consecutive passes (five passes or more) is more effective in exploiting imbalances in the opponent’s defence than in creating space by dislocating defenders in a balanced defence [4]. Possessions with relatively longer duration were related with successful teams [5, 20]. Such performance is indeed more expected from skilful players, with different and/or better tactical and technical proficiency, at the higher rather than lower level of play [20]. Teams regained and started possession more often in the defensive half of the pitch (81%) [4, 23, 27, 31]. Regains in the attacking third with high pressure defensive style can also influence scoring opportunities because the ball can be regained closer to the opponent’s goal, while also increasing the likelihood of facing an imbalanced defence [29, 30, 32]. Furthermore, successful teams scored more goals from possessions started in the midfield zone compared with unsuccessful teams. This is because scoring from possessions starting from longer distances to the opponent’s goal demands players with a high level of playing skill that is often found in successful teams [4, 20]. As mentioned above, attacking performance is a complex process influenced by several variables. However, most of these previous studies have analysed the data with targeting all attacking patterns including direct attack and elaborate attack. In the present study, we analysed the number of passes, duration, and starting zone whilst confining analysis to direct attack and verified the influence of opponent quality on these attacking characteristics. Consequently, the difference in characteristics in direct attack failed to be distinguished against superior and inferior rank teams. These results might indicate that the characteristics of direct attack for goal scoring partially have a commonality and are uninfluenced by opponent quality. Briefly, it would appear from the present data that attacking with two passes, within 10 seconds and starting at the offensive half are more effective for goal scoring from direct attack. There were a few limitations in the present study. First, the analysed data were obtained only from Japanese professional league. These results may be useful in characterizing the Japanese league and accomplishing good performances in the league. However, samples from a higher or lower level of play than the Japanese professional soccer league may lead to a different outcome. In fact, in a previous study it was pointed out that there is a possibility that teams at higher level of play have players with the necessary skills to sustain long passing sequences, and therefore have a better chance of scoring more goals [20]. For the clarification of the importance of goal scoring in direct attacking play, similar analysis is needed with different samples, for example: the big-five leagues in Europe; European cups; or World cups. Second, we sampled attacks only achieving goals. In order to reveal the effectiveness of direct attack, it was necessary to assess direct attacks not achieving goals. Finally, attacking performance in soccer is a complex process influenced by several situational variables [22]. In this respect, the behaviours of the players and teams involved in attacking styles of play seem to strongly depend on the type of competition [23], on game location, i.e. home/away factor [6, 19, 24], and on match status, i.e., when the teams are winning, losing or drawing [6, 17, 18, 25]. Furthermore, opponent attacking pattern of play which is referable to opponent quality seems to influence attacking performance [33]. Although these situational factors might affect team’s performance, our present study have been conducted based on only unidimensional quantitative data. The inclusion of multidimensional qualitative evaluation may improve our ability to describe team attacking styles in soccer [20, 34].

5. Conclusions

- In conclusion, our findings suggest that effectiveness of direct attack for goal scoring becomes higher in when the opponent quality is superior. In contrast, the characteristics of direct attack were not affected by opponent quality. Direct attack with two passes, duration of 10 seconds or less and starting at the offensive half is thought to be common pattern of goal scoring against superior and inferior opponent in order to improve their goal scoring ability. The information can be useful for coaches and players planning and practising to improve a team’s goal-scoring and goal-preventing abilities. However, further analysis with consideration for the factors affecting goal scoring including technical, physical and tactical factors are needed for better understanding the influence of opponent quality on attacking styles.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML