-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2017; 7(4): 170-176

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20170704.03

Post-Activation Potentiation and the Shot Put Throw

Marcus Dolan1, Trish G. Sevene2, Joe Berninig3, Chad Harris4, Mike Climstein5, Kent J. Adams2, Mark DeBeliso1

1Southern Utah University, Department of Kinesiology and Outdoor Recreation, Cedar City, UT, USA

2California State University Monterey Bay, Kinesiology Department, Seaside, CA, USA

3New Mexico State University, Department of Kinesiology and Dance, Las Cruces, NM, USA

4Metropolitan State University of Denver, College of Professional Studies, Denver, CO, USA

5The University of Sydney, Exercise, Health & Performance Faculty Research Group, Sydney, NSW, AUS

Correspondence to: Mark DeBeliso, Southern Utah University, Department of Kinesiology and Outdoor Recreation, Cedar City, UT, USA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Acute post activation potentiation (PAP) is a physical conditioning activity that incorporates intense muscle activation to enhance muscular force production. Practical applications of PAP as a conditioning activity to enhance sport performance are of interest to athletes and coaches. PURPOSE: This study compared the effects of a dynamic warm-up and a dynamic warm-up followed by a PAP conditioning activity on shot put throw distance. METHODS: NCAA Division I male (n=6) and female (n=7) track and field athletes volunteered as participants for the study. The study employed a randomized repeated measures crossover design where each participant was randomly placed into one of two groups. During the first test session one group performed a dynamic warm-up followed by an 8-minute rest period then a shot put throw test. The other group performed a dynamic warm-up followed by a PAP conditioning activity comprised of 3 repetitions of a hang clean and jerk at 80% 1-RM followed by an 8-minute rest period then a shot put throw test. During week 2 the two groups crossed over with respect to the warm-up conditions and repeated the shot put throw test. Three shot put trials were collected following each warm-up condition and the best score was used for subsequent analysis. The shot put throw distances were compared between warm-up strategies with a paired t-test. RESULTS: The shot put throw scores were: PAP 10.93±1.81* and non-PAP 10.57±1.84 meters (p=0.007). CONCLUSION: Within the parameters of this study, when compared to a standard dynamic warm-up, a dynamic warm-up strategy that includes a PAP event significantly improves shot put throw performance. Coaches and athletes could apply the dynamic warm-up that includes a PAP conditioning activity as implemented in this study to enhance shot put performance during competitive scenarios.

Keywords: Shot Put, Hang Clean and Jerk, PAP

Cite this paper: Marcus Dolan, Trish G. Sevene, Joe Berninig, Chad Harris, Mike Climstein, Kent J. Adams, Mark DeBeliso, Post-Activation Potentiation and the Shot Put Throw, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 7 No. 4, 2017, pp. 170-176. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20170704.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Post-activation potentiation (PAP) is a phenomenon where by an acute increase in maximal muscle activation occurs following a conditioning activity executed at a high intensity [44]. Resistance exercises that target a muscle group followed by a defined rest period have led to an increase muscular power output via a PAP effect [4, 7, 10, 15, 21, 24, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 35, 39, 42, 45-47]. PAP induced via a conditioning activity prior to competition may provide an additional benefit beyond a dynamic warm-up (WU) [44].There are several programmatic challenges that must be addressed prior to enhancing athletic competitive performance utilizing the PAP phenomenon [26]. The intensity of the conditioning activity must be high enough to induce a measureable PAP effect, but not so intense as to produce fatigue. Another programmatic issue deals with the rest period separating the conditioning activity and the execution of the performance activity [44]. Regarding PAP, a muscle’s contraction history may influence the mechanical performance of proceeding muscle contractions. With that said, should the muscle’s contractile history generate extreme fatigue, performance could be degraded. As such, muscle activations at high intensity combined with an adequate duration of rest should lead to a meaningful PAP response [22, 44].The period in which the effectiveness of PAP persists is unclear [25, 29, 31, 39, 46]; the lengthier the rest period, the better the recovery from the fatigue of the PAP conditioning activity. Congruently, a lengthier rest period leads to a declined PAP response [34, 44]. The results of previous research suggest that a rest period ranging from 8-12 minutes between the conditioning activity and the targeted activity is effective [9, 10, 12, 15, 23, 25, 30, 32, 33, 36, 38, 44]. Recovery periods less than 2–3 minutes are apparently insufficient because the impact of the conditioning activity fatigue offsets the potentiation effect. Recovery (rest) periods longer than 12 minutes are typically not successful as, “the enzyme responsible for deactivating the enhanced muscle fibers may have completely eliminated the effects of the initial potentiation” [45]. Hence, from a programmatic standpoint, determining the rest period where PAP is optimized is a crucial challenge.An additional programmatic concern relates to the training status of an individual. The National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) suggests that PAP should be reserved for individuals with high relative strength [33] as the PAP phenomena does not manifest to a meaningful level in individuals with low relative strength [33].Acknowledging the aforementioned programmatic challenges, PAP has been demonstrated to contribute to acute enhancements in lower and upper body power output [4, 7, 10, 15, 21, 24, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 35, 39, 42, 45-47]. Muscular power output is essential to athletic performance (e.g. jumping, sprinting, and throwing). Hence, developing a PAP protocol that synchronizes a PAP potentiated state with athletic competition could lead to improved performance by the athlete during the competition.In the current study we attempted to determine if a dynamic WU followed by a PAP conditioning activity could improve performance in the shot put throw distance to a greater degree when compared a dynamic WU alone. It was hypothesized that the PAP conditioning activity would lead to a greater shot put throw distance.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

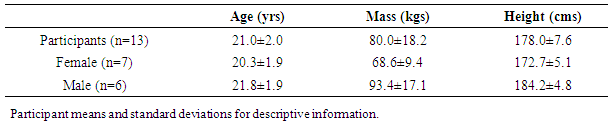

- Participants were a convenience sample of 13 volunteer NCAA Division I male and female (6 male and 7 female) track and field athletes from Utah Valley University. Due to the specific nature of this study only male and female athletes who competed in the field event of shot put and multi-events of decathlon (male) and heptathlon (female) were given the opportunity to volunteer for this study. Ages of the participants ranged from 18-25 years old and were injury free at the time of the study.Permission was sought (and granted) by all of coaches associated with the participants before asking for athletes to participate in this study. Approval by an Institutional Review Board to engage human subjects in research was obtained before conducting the study interventions or assessments. Further, participants were presented a written consent form to read and sign before any action in the study was taken.

2.2. Instruments and Apparatus

- The study was conducted at the campus of Utah Valley University. All warm-ups, pre-tests and post-tests were done at the Hal Wing Track and Field Stadium. The shot put throws were conducted at the Hal Wing shot put pits. A metric measuring tape was used to measure the distance of each shot put throw. A 20.45 kg Olympic style barbell and weighted plates (1.14 – 20.45 kgs) were used for the purpose of executing the hang clean and jerks.

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1 Assessment

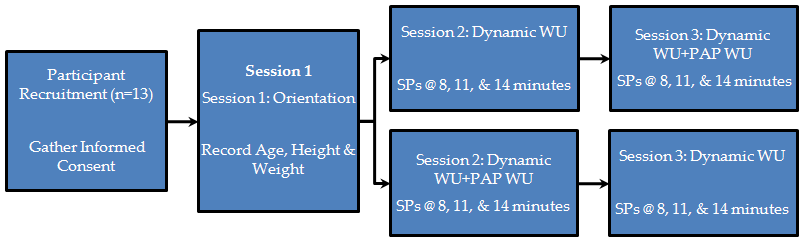

- Session 1 consisted of recording the participant’s age, height, and weight. The researcher then reviewed the procedures that would be employed to conduct the study (figure 1). The participants were then randomly separated into two groups.

| Figure 1. Chronology of study events. PAP-post activation potentiation; SPs-Shot Puts; WU-warm-up |

2.3.2. Dynamic Warm-up

- The dynamic WU protocol was used for sessions two and three for both groups. The dynamic WU consisted of (fixed order): 5-minute moderate intensity stationary bike, 20 meter A-Skips, 20 meter lunges, 20 meter high knee butt kicks, 20 meter knee hugs, 20 meter B-skips, 20 meter side lunges (alternating left and right), 20 meter skips with arm swings, 20 meter glute walks, 20 meter leg sweeps (hamstring warm up), 20 meter reverse lunges, 20 meter walking quad/hamstring stretch, 20 meter straight leg bounding, 5 regular pushups, 5 wide pushups, 5 narrow pushups, 10 leg swings (10 isolating hamstring/ground and 10 isolating adductors and glutes), 10 medium arm circles and 10 large arm circles.

2.3.3. PAP Warm-up Sets

- Following the dynamic WU the participants performed 3-4 warm-up sets of hang clean and jerks with 120-180 seconds rest between each set (8-10 repetitions @ unloaded Olympic bar, 6-8 repetitions @ 30% 1-RM, 5 repetitions @ 50% 1-RM, and 3-4 repetitions @ 70% 1-RM). Following a 180 second rest period the participants performed the three sets of hang clean and jerks with 180 seconds rest between each set (3 repetitions @ 80% 1-RM). These three culminating sets were considered the PAP conditioning activity.The 80% of 1-RM intensity of the hang clean and jerk was based on recently collected 1-RMs established during training sessions that were monitored by the strength and conditioning coach (who is also the lead investigator).

2.3.4. Shot Put

- The shot put throws were carried out on a NCAA regulation shot put pit. The shot put sizes were 4 kilograms for the female athletes and 7.26 kilograms for the male athletes. The shot put throws were measured to the nearest 0.5 cm. Throws that did meet regulations (fouls) were not recorded.The interclass reliability of the shot put throws in our study was r=0.994 (based on the analysis of the best two throws recorded following the dynamic WU only condition).

2.3.5. Statistical Analysis

- The study employed a randomized repeated measures cross over design. The shot put distance was the dependent variable (DV) analysed in this study. A paired t-test was used to compare the mean shot put throw distance between the two warm-up strategies (dynamic WU vs. dynamic WU and a PAP conditioning activity). An alpha was set a priori at α≤0.05 as the threshold for statistical significance. Given the growing controversy surrounding “statistical significance” and replication of study results [2], we also included analysis of percent change between conditions as well as effect size. Statistical calculations and data management were conducted with Microsoft Excel 2013.

3. Results

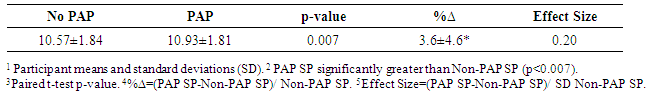

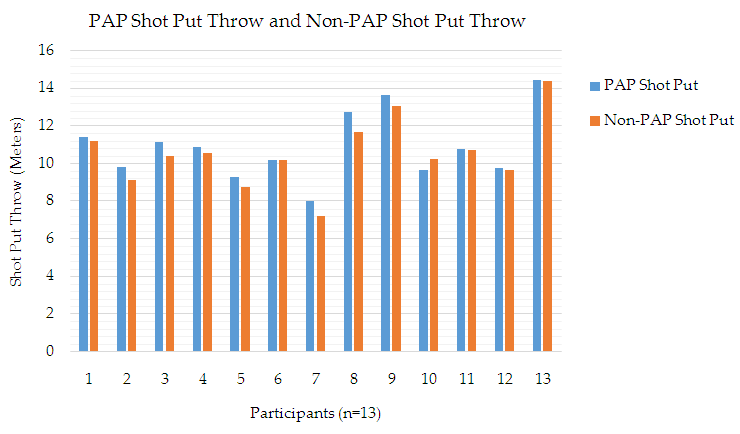

- The 13 participants completed all of the study procedures without complication or injury. Table 1 details the participant’s descriptive information for age, height, and mass (mean ± standard deviation).The mean non-PAP and PAP shot put throws (meters) were 10.57±1.84 and 10.93±1.81 respectively. The shot put throws following the PAP conditioning activity were significantly greater than the non-PAP shot put throws (p<0.007) representing a 3.6% increase. The effect size (ES) of the increase in shot put throws was ES=0.20 (see Table 2). Twelve of the thirteen participants had a greater shot put throw distance following the PAP conditioning activity (see Figure 2).

|

|

| Figure 2. Participant best shot put throws distance with and without a PAP conditioning activity |

4. Discussion

- The purpose of this study was to determine if a dynamic WU followed by a PAP conditioning activity comprised of 3 sets of the hang clean and jerk @80% of 1-RM could lead to improved performance in the shot put throw distance when compared to a dynamic WU alone. It was hypothesized that the dynamic WU, plus PAP conditioning activity would have a significant positive effect on the participant’s shot put throw distance.The shot put throws that followed the PAP conditioning were significantly greater (3.6%: p=0.007: ES=0.20) when compared to the shot put throws performed following the dynamic WU alone. While the percent improvement and ES may seem small, a 3.6% increase in shot put throw distance (≈36 centimeters) is considered very meaningful to the coaches and athletes as placement at competitions is often separated by a few centimeters. For example, at the 2017 NCAA Track and Field Championship the 2nd-8th placing shot put throws for men were as follows: 20.38, 20.08, 19.70, 19.63, 19.53, 19.49, and 19.26 meters. A 3.6% improvement in any of these scores would make a difference in placement (ex. the 4th place finisher would have the silver medaled). This same scenario holds true for the 2017 NCAA Track and Field Championship shot put throws for women.Twelve of the thirteen athletes improved their shot put throw distance following the PAP conditioning activity. The one athlete who did not improve following the PAP conditioning activity fouled on two of the three shot put attempts and hence those two shot put throw distances were not recorded. As such, it is possible that the athlete did experience a potentiating effect but was not able to demonstrate so due to the missed shot put throw attempts. It is also worth noting that there were a total of 6 missed attempts (fouls) by the athletes during the non-PAP shot put throws and 5 following the PAP conditioning activity. Given the improvement in shot put throw distance following the PAP conditioning activity and in the absence of additional fouls, it appears that 8-minutes was sufficient rest to mitigate the effects of fatigue associated with the conditioning activity. The post conditioning activity rest period of 8 minutes used in this study was based on the average of rest periods used in earlier studies that improved vertical jump height and/or sprint speed [9, 10, 12, 15, 23, 25, 30, 32, 33, 36, 38, 44].The increase in shot put throw distance following the PAP conditioning activity used in this study is agreement with prior studies that have demonstrated meaningful increases in upper and lower body muscular power output due to a PAP conditioning activity with rest periods ranging from 6-12 minutes [1, 4, 5, 7, 10, 11, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 24, 25, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 35, 39, 42, 43, 45, 46, 47].A successful PAP protocol is based on an optimal stimulus that allows the co-existence of fatigue while the muscle is in a potentiated state [34, 40]. The current study used 3 sets of 3 repetitions @80% of 1-RM of hang clean and jerks. The results of the study suggest that the intensity of the PAP conditioning activity was sufficient to induce a meaningful potentiated state which is consistent with the successful intensity range (60-100% of 1-RM) reported by the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) [33].The NSCA Hot Topics states that the bench press along with variations of the back squat are the most frequently used exercises for the purpose of a successful PAP conditioning activity [33]. There have been numerous studies that have used high intensity back squats as a conditioning activity to increase lower body power [7, 10, 15, 21, 24, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 35, 39, 42, 45-47]. The potentiating exercise selected for this study was the hang clean and jerk. We choose the hang clean and jerk for three primary reasons. First, just the barbell and weights were required which could be made readily available near a shot put pit. Second, we felt from a specificity stand point that the hang clean and jerk would tax similar musculature and mechanics as the shot put albeit the Olympic lift derivatives are primarily axial load force vectors [8]. Third, Harris and colleagues successfully employed a PAP protocol that used a jerk as the potentiating activity at improving shot put throwing velocity [24]. We are unaware of any study employing the hang clean and jerk as the PAP conditioning activity noting that the power clean has been successfully used as a conditioning activity to increase sprint speed [16, 37]. Future research should focus on using simpler Olympic lifting derivatives as a conditioning activity for the shot put as differing weightlifting derivatives are known to impact the force-velocity curve in varying ways, and therefore may enhance the PAP effect [41].The NSCA’s position is that an athlete’s training status is likely the largest factor leading to a meaningful level of PAP [33]. Prior studies indicate that PAP manifests to a greater degree in advanced trained individuals when compared to recreationally trained individuals [3, 6, 13, 14]. The current study’s participants were NCAA Division I track and field athletes who competed in the field event of shot put and/or multi-events of the decathlon (male) or heptathlon (female). In other words, all of the participants were highly trained athletes who were proficient at throwing the shot put. The training status of the athletes likely contributed positively to the success of the PAP protocol employed in this study. It is also worth pointing out that the results of this study carry a large degree of external validity as all the participants were competitive collegiate athletes, proficient shot put throwers, and the study was conducted during the competitive season. Hence, extrapolating the results of this study for the implementation of like athletes competing in season is not a stretch. In order to bring the results of this study to the competition environment there are a few issues to be addressed. First, simply bring weights and an Olympic bar to the field venue in near proximity of the shot put throwing pit. Next, the dynamic WU and subsequent PAP conditioning activity need to be completed in a manner such that there is at least an 8-minute rest period prior to the shot put throw attempts. The current study had shot put throw attempts that occurred at 8, 11, and 14-minutes subsequent to the conditioning activity. With that said, a coach or an athlete might attempt to stretch the potentiated period as Kopp and colleagues did [26]. In Kopp’s study, super sets of back squats to Romanian dead lifts (RDL) were used as the conditioning activity. The first superset was conducted (5-RM back squat to RDL 5-RM) followed by an 8-minute rest period then a VJ. Next, the second same super set was executed followed by an 8-minute rest period then a VJ. Finally, the third same super set was executed followed by an 8 minute rest period then a VJ. Hence the total potentiated period was over 24-minutes. It is possible that scheduling the conditioning activity of the current study (hang clean and jerk) to match the intermittent process of dispersing the conditioning activity between shot put throw attempts might extend the potentiated period to more closely match the spacing in throw attempts in throwing competition.

5. Conclusions

- Within the parameters of this study it can be concluded: a) there was a meaningful improvement in the shot put throw distance following a PAP conditioning activity comprised of the hang clean and jerk (3 sets of 3 repetitions at 80% of 1-RM); b) there was not an increase in the number of shot put throws scored as fouls following the PAP conditioning activity; c) the 8-minute rest period following the PAP conditioning activity provided sufficient recovery from fatigue; and d) the results of this study suggest that if appropriately timed, the PAP conditioning activity used in this study could be used in a track and field competitive environment for the purpose of improving the shot put throw distance.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML