-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2017; 7(3): 137-143

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20170703.07

Influence of Eccentric, Concentric, and Dynamic Weight Training Actions on the Responses of Pleasure and Displeasure in Older Women

Sandro dos Santos Ferreira1, Kleverton Krinski2, Ragami Chaves Alves1, Lucio Follador1, Erick Doner Santos Abreu Garcia1, Aldo Coelho Silva1, Vinicius Ferreira dos Santos Andrade1, Maressa Priscila Krause3, Sergio Gregorio da Silva1

1Department of Physical Education, Federal University of Parana, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

2Federal University of Sao Francisco Valley, Brazil

3Federal Technological University of Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

Correspondence to: Sandro dos Santos Ferreira, Department of Physical Education, Federal University of Parana, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The aim of this study was to assess the influence of eccentric, concentric, and dynamic weight training actions on pleasure and displeasure responses in older women during and after the exercise session. Fourteen elderly women (age 68.5 ± 4.6 years) participated in the study. All the subjects completed five exercise sessions: (a) familiarization, (b) determination of 1 RM (Repetition Maximum), and (c) three sessions of weight training: one session with eccentric actions, one with concentric actions, and one with dynamic actions (concentric and eccentric). The subjects performed five exercises per session: chess press, leg extension, lat pulldown, leg curl, and lateral shoulder raise. The responses of pleasure and displeasure were measured after each series of exercise and 30 min after the exercises session, along with the subjective perception of the session. The statistical analysis used was analysis of variance for repeated measures. No significant differences were found between the responses of pleasure and displeasure obtained during and after the session (session method). Concentric sessions showed differences compared with dynamic and eccentric sessions. The responses of pleasure and displeasure can be measured by the session method in older women during exercise sessions involving concentric, eccentric, and dynamic actions. The practical application of this method may assist health professionals in monitoring training sessions with weights.

Keywords: Resistance Training, Exercise Prescription, Elderly

Cite this paper: Sandro dos Santos Ferreira, Kleverton Krinski, Ragami Chaves Alves, Lucio Follador, Erick Doner Santos Abreu Garcia, Aldo Coelho Silva, Vinicius Ferreira dos Santos Andrade, Maressa Priscila Krause, Sergio Gregorio da Silva, Influence of Eccentric, Concentric, and Dynamic Weight Training Actions on the Responses of Pleasure and Displeasure in Older Women, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 7 No. 3, 2017, pp. 137-143. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20170703.07.

1. Introduction

- Weight training is widely recommended for elderly population, due to its benefits [1, 2]. It is important to consider that a weight training program can involve eccentric, concentric, and isometric muscle actions, which can be performed together or separately. Concentric actions (CON) occurs when the point of origin and insertion of the muscle promotes muscle shortening during contraction. When these same points deviate, the muscle-lengthening phase of the eccentric action (ECC) occurs. The generation of tension without changes in joint angle is defined as isometric action (ISOM) [3, 4]. Weight training programs generally includes primarily dynamic repetitions (DYN), which involve both CON and ECC and consider the use of secondary ISOM [3].In recent decades, studies have shown that ECC, CON, and DYN exercises can improve the cardiovascular system, muscle mass, and the functional capacity in elderly subjects [5, 6]. However, the benefits from training are dependent on the correct prescription and the appropriate control of exercise intensity [4].Recent research has proposed the use of different methods and techniques during exercise sessions in order to observe how subjects feel during the exercises [7-9]. Using the responses of pleasure and displeasure to relate to psychophysiological sensations in physical activity has been touted as an important tool for adherence in exercise programs [10, 11]. Pleasure and displeasure responses come from the term basic affect, in which it refers to the responses of valences or central experiences that present distinct states (ex: positive or negative, pleasure or displeasure), including, but not limited to, emotions and moods [12]. In physical exercise, individuals seek intensities that maximize the feelings of pleasure and minimize the feelings of displeasure [13-15].In endurance exercise, the intensity in which the exercise is performed interfere on pleasure and displeasure responses [13]. According the dual mode theory [12], exercise intensities below the ventilatory threshold (VT), tend to present pleasurable responses, and intensities above the VT tend to have unpleasant responses [16, 17]. Weight training in ECC, CON, or DYN actions may provide differences in exercise intensity; however, other variables such as load and volume, order and exercise selection, recovery periods, and execution speeds are elements that can be manipulated during exercise with weights to promote high degrees of pleasure and displeasure and physiological benefits to practitioners [4, 18].The traditional method of measuring the responses of pleasure and displeasure has been performed at the end of each series of exercise, reflecting various points throughout the session. In order to facilitate and simplify the measurement of the responses of pleasure and displeasure, Haile, Goss [19] measured them in a single moment after the exercise session. This procedure is similar the measure of the intensity of the exercise session (subjective perception of the session - RPE-S) [20-23]. However, there are limited studies that found the responses of pleasure and displeasure by the session method [19, 24], and so far, no investigations of this nature in older women were observed.Thus, the present study aims to assess the influence of eccentric, concentric, and dynamic weight training actions on pleasure and displeasure responses in older women during and after the exercise session.

2. Materials and Methods

- A sample of 14 older women met the inclusion criteria and all participants gave their written consent to participate in this study. All were classified as either physically active (regular exercise ≥ 3 days week) or as having no former weight training experience. The inclusion criteria were (a) between the ages of 60 and 75, (b) ability to take part in regular physical exercise, and (c) negative responses to all questions in the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q), (d) a body mass index (BMI) between 18.5 and 30 kg⋅m-2, and (e) a personal statement of not having smoked in the last 12 months. Criteria for exclusion included the presence of cardiovascular, metabolic, or orthopedic disease, or any other contraindications as determined by their medical history from the previous 12 months. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Health Sciences at the Federal University of Parana (UFPR) in Curitiba, Brazil - n° CAAE: 0014.0.091.000-11.The experimental design of this study can be classified as cross-sectional. All subjects completed five sessions of exercise: (a) sample screening and familiarization, (b) determination of 1RM (Repetition Maximum), and (c) three sessions of weight training conducted on different days, with 24–48 h between sessions with the orders counterbalanced. Each session involved a different protocol: (1) ECC-only exercise, which consisted only of stretching of the muscle length and angle joint, (2) CONC-only exercise, which consisted of only the shortening phase of the muscle and angle joint, and (3) DYN = CONC + ECC, which consisted of both the lengthening and shortening phase. The responses of pleasure and displeasure and session RPE were recorded during each experimental session. Thus, the independent variable was muscle action (ECC-only, CONC-only, and DYN), and the dependent variables were pleasure and displeasure and session RPE. The subjects were advised not to consume alcohol, caffeine, or practice vigorous physical activity 24 h prior to each test.To facilitate the elderly participants’ understanding of the experimental procedures, the subjects performed a familiarization session. Instructions were provided on the correct execution and proper form of the prescribed exercises, mainly regarding the appropriate posture, the utilization of a constant range of motion, and movement speed. The 1RM testing session began with a specific warm-up, consisting of five to eight repetitions of each exercise using a self-selected, light weight. After this initial procedure, subjects were requested to take 5 min for passive recovery. The determination of the 1RM load was executed over a maximum of four attempts for each exercise with 3 min of rest. Therefore, in each attempt, a weight was successively added until only one repetition (completed with good form) was successfully lifted, or until the participant indicated that she could not lift any more weight. Thus, the 1RM test was performed with each resistance exercise (chest press, leg extension, lat pulldown, leg curl, and lateral shoulder raise). To reduce the possible cumulative effect of fatigue on 1RM performance, the exercise order was alternated between upper and lower body exercises to allow greater recovery. All the subjects were familiarized with the experimental procedures and were subjected to different exercise intensities (low, moderate, and high) for all the mentioned exercises. Consequently, this facilitated the estimation of the initial loads and subsequent increments on 1RM tests.All subjects completed three sessions of weight training, which were conducted on different days and with the orders counterbalanced. Thus, each weight training session was categorized according to the type of muscle action (CONC-only, ECC-only, and DYN). To guarantee the correct execution of the exercise and load application, each weight training session and each exercise were supervised by two experienced fitness instructors. In addition, during the CONC-only and ECC-only weight training sessions, the subjects received help from two instructors, which allowed for these exercises to be performed in an isolated manner. Therefore, during the CONC-only session, the subjects lifted the weight for the complete execution of each movement (shortening of muscle length and angle joint), whereas two fitness instructors reduced the weight during the eccentric phase. During the ECC-only session, two fitness instructors lifted the weight for each repetition, and then the subject used strength to lower the weight (stretching of muscle length and angle joint). During the DYN session, both muscle actions (ECC and CONC) were performed without the help of instructors, and supervision was used to verify the correct execution of the exercise.The weight training sessions (CONC-only, ECC-only, and DYN) consisted of uniarticular and multiarticular exercises, free weights, and machines (Nakagym, São Paulo, Brazil) for large and small muscle groups, based on three sets of 8–10 repetitions each [2]. Thus, all the weight training sessions adopted the following exercises: chest press, leg extension, lat pulldown, leg curl, and lateral shoulder raise, with the order alternating between upper and lower body exercises. All exercises were performed on machines with the exception of the lateral shoulder raise, which used free weights. The intensity of each weight training session was classified as follows: CONC-only (70% 1RM), ECC-only (90% 1RM), and DYN (70% 1RM). According to Hortobagyi and Katch [25], 90% 1RM with the eccentric action is equivalent to 70% 1RM with the concentric force.The execution speed of the exercises was controlled by verbal commands from the evaluator, such that the subject maintained a concentric to eccentric phase ratio of 2:2 s, in accordance with the procedures suggested by Kraemer and Ratamess [3].Session RPE was measured 30 min after the end of the training session following the procedures described by Foster et al. [22]. The subject was presented with the OMNI-RES scale, which ranges from 0 to 10, and was asked to answer the following question: “What level of exertion did you feel in your body during the training session?” The subjects were instructed to consider only the overall perception of exertion. While the subjects were waiting, they were allowed to drink water if they wished, but they were not allowed to perform other tasks such as eating or showering.The responses of pleasure and displeasure were determined by the feeling scale of Hardy and Rejeski [26]. This instrument consists basically of an 11-point scale, with single, bipolar items, ranging from +5 (“very good”) to −5 (“very bad”), and zero on the scale considered neutral [27]. The responses of pleasure and displeasure were measured after each set of exercises and 30 min after the end of the training session, similar to the procedures described by Haile, Goss [19]. The feeling scale [26] was presented to the subject, who was asked to answer the following question: “What feeling of displeasure/pleasure did you feel during this entire exercise session?” The subjects were instructed to consider only the overall feeling of the session. While the subjects were waiting, they were allowed to drink water if they wished, but they were not allowed to perform other tasks such as eating or showering.The treatment of the data employed descriptive statistics with mean ± standard deviation (SD) to characterize the study participants. The analysis of variance for repeated measures was used to identify possible differences in the responses of pleasure and displeasure observed during the training session and after and to analyze the interaction between training sessions and perceptual responses to pleasure and displeasure. In the presence of violations for the assumptions of sphericity, Greenhouse–Geisser corrections were employed. The magnitude of effect was calculated using partial eta squared (η2p). The main effects and interactions were analyzed using post-hoc Bonferroni test.The significance level for the analysis was p < 0.05. Data were statistically analyzed using the computer program SPSS (version 17.0).

3. Results

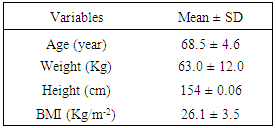

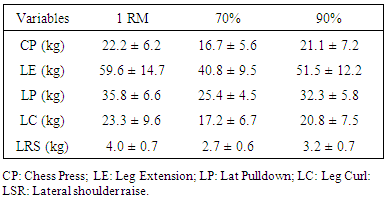

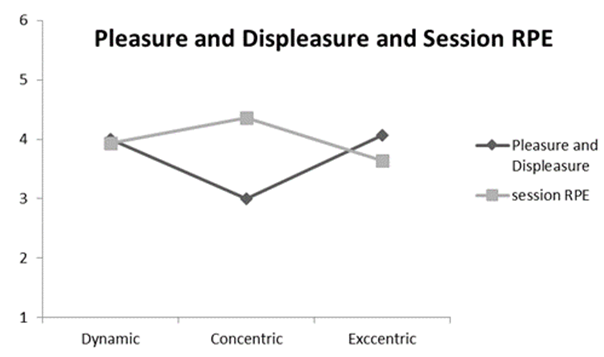

- The corresponding values for age and anthropometric measurements are shown in Table 1, as mean ± standard deviation (SD). In Table 2, the values of 1RM, 70% 1RM for DYN, CONC, and 90% of 1 RM for ECC are shown for each exercise session.

|

|

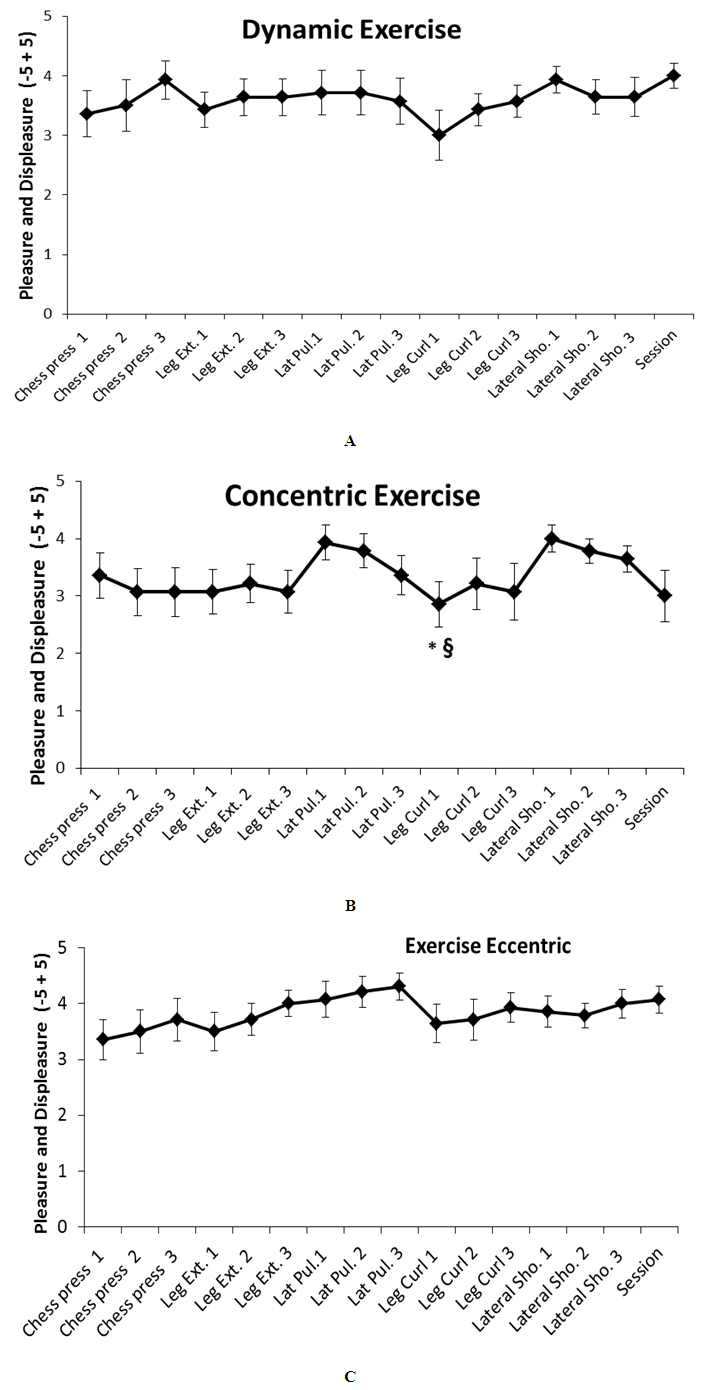

| Figure 2. Interaction between perceptual and pleasure and displeasure responses |

4. Discussion

- The purpose of this study was to investigate the responses of pleasure and displeasure of the session during different types of weight training in older women. The results confirmed that the responses of pleasure and displeasure involving eccentric, concentric, and dynamic actions are similar to those observed during the series, and exercise sessions involving different muscle actions may differ among themselves.Strategies to measure affective responses and/or pleasure and displeasure have been employed in order to study the behavior of this variable during exercise [18, 28, 29]. The circumplex model [9] and exercise prescription, based on the feeling scale [8, 26], are methods developed in recent decades aimed to relate emotional states and/or pleasure and displeasure with exercise.The measurement of the responses of pleasure and displeasure in most studies has primarily been studied in aerobic exercises. Haile et al. [19] noted that during exercise, the self-selected responses of pleasure and displeasure after the exercise session are not consistent with those obtained during the exercise session; however the activity imposed, the results are consistent with those found in this study, demonstrating similar responses during and after the session. Importantly, this study is the first to study the responses of pleasure and displeasure during weight training in older women.The study of Haile et al. [19] also noted the responses of pleasure and displeasure every five minutes (during 20 min of exercise and 15 min of recovery), and the results show that the responses of pleasure and displeasure change over time and can differentiate and/or influence the sessions. In the present study, the responses of pleasure and displeasure were observed after each set of exercise and were compared with the overall feeling of the session. Only in the first set of leg curl exercise with eccentric action were there differences. However, these differences did not significantly influence the response of the session relative to other exercises and for the sessions with dynamic and concentric actions. This analysis suggests that aerobic exercise and resistance exercise may have different responses of pleasure and displeasure during and after the session; however, further investigations should be carried out.Studies conducted in the context of aerobic activities found that affective responses are influenced by exercise intensity [14, 15, 30]. In exercises at moderate intensity, the responses show homogeneity to the feeling of pleasure, while for severe intensity the sensation is facing the displeasure. During heavy intensity exercises around the transition of aerobic/anaerobic states, a variability in affective responses related to pleasure/displeasure occurs, having a great influence on individuals [31].In weight training, the fields of intensities are influenced by several variables (number of sets, interval between sets, number of repetitions, etc.); however, when controlled, the percentage of 1RM or 10RM are parameters to define the intensity of effort [3]. Little is known about the intensities and responses of pleasure and displeasure in weight training. In the study of Bibeau et al. [29] that investigated different intensities and recovery periods, the weight training in affective responses and anxiety from mild to moderate exercise (50%–55% of 1RM) promoted an increase in positive affect and a decrease in negative affect.In the investigation of Arent et al. [32], who studied the influence of exercise intensity with weights in anxiety and affective responses, the moderate exercise (70% 10 RM) provided greater affective responses than exercise at low (40% 10 RM) and high (100% 10 RM) intensities, corroborating the findings of aerobic exercise.In the present study, all the sessions were performed 70% 1 RM; however, the CON session showed lower degrees of pleasure and displeasure compared with the DYN and ECC sessions. Contrary to these findings, in young women of college age, Miller et al. [18] did not observe differences in emotional responses between eccentric, concentric, and dynamic actions; however, the responses of heart rate and RPE were lower in ECC actions. Hortobagyi et al. [33] showed that senescence can influence RPE and the responses of pleasure and displeasure, once aging concentric force have a more pronounced decrease (31 newton’s per decade) that the eccentric force (9 newton’s per decade). This observation led to the hypothesis that elderly individuals who start weight training tend to make a greater effort in the CONC activity than in the ECC activity.The responses of pleasure and displeasure in each session were also observed with the perceptual responses of the session, in which interactions were found between the variables. This phenomenon was discussed in the review study conducted by Ekkekakis et al. [13], which suggests that the exercise intensity and responses of pleasure and displeasure can inversely relate in some populations. This research emphasizes that individuals with sedentary or low to moderate fitness levels, who have lower perceptual responses of exercise, tend to express higher responses of pleasure.

5. Conclusions

- The results of this study demonstrate that pleasure and displeasure responses can be measured by the session method in older women and can be applied in exercise sessions involving concentric, eccentric, or dynamic actions. The practical application of this method may assist health professionals in monitoring training sessions with weights, aimed to reduce the responses of displeasure and stimulate the pleasurable responses related to exercise, and reduce the possibility of the abandonment of the subject by the trainer.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML