-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2017; 7(3): 105-110

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20170703.02

Emotional Intelligence and Coaching Behavior of Sport Coaches in the State Universities and Colleges in Region III, Philippines

Arlene Dave, Elizabeth N. Farin, Anniebeth N. Farin

Research, Extension, Training, Gender and Production Ramon Magsaysay Technological University, Iba, Zambales, Philippines

Correspondence to: Elizabeth N. Farin, Research, Extension, Training, Gender and Production Ramon Magsaysay Technological University, Iba, Zambales, Philippines.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This is a descriptive and correlational study that examined the relationship between emotional intelligence and coaching behavior of the sport coaches in the state universities and colleges in Region III. A total of 662 respondents, 165 coaches and 497 athletes were the respondents of the study. The study describes the perception of the respondents’ emotional intelligence in terms of emotional awareness, managing emotions, self-motivation, empathy, and coaching others’ emotions. The sport coaches and athletes indicate that the emotional intelligence of sports coaches was high. They were emotionally aware, can manage one’s emotion, self-motivated and empathetic. The coaching behavior of the sport coaches displayed during selection of athletes, during practices, before the game, during the game and after the game was described as very high positive. The coaching behavior of the sport coaches displayed during selection of athletes, during practices, before the game, during the game and after the game was perceived by the athlete-respondents to be high positive. The findings suggest that the sport coaches need to increase the level of their emotional awareness through emotional intelligence seminar-workshops. To maintain their very high positive coaching behavior, a continuing high quality coaching education program should be provided by the entire state universities and colleges in Region III.

Keywords: Emotional Intelligence, Coaching Behaviour, Sport Coaches, Philippines

Cite this paper: Arlene Dave, Elizabeth N. Farin, Anniebeth N. Farin, Emotional Intelligence and Coaching Behavior of Sport Coaches in the State Universities and Colleges in Region III, Philippines, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 7 No. 3, 2017, pp. 105-110. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20170703.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Emotions affect the way people think, act, decide and communicate. Emotions exert an incredibly powerful force on human behavior and explained that strong emotions can cause one to take actions not normally performed, or avoid situation that is generally enjoyed [3]. Handling emotions is essential skill a leader must have. One must first identify and recognize his own and others’ negative and positive emotions so that he can manage self-control and build good relations with others. This ability is known as emotional intelligence.In sport, coaching behaviours in practice, at games, and away from the sport have strong influences on players and can impact both players' performances and continued participation. It was affirmed that coaches' styles and behaviours have a great effect on team performance and stressed the relationship between coaches' behaviours and team success [9]. If athletes disagreed with the coach’s goals, personality, and/or beliefs, some of the psychological needs of the players were not met. Failure often resulted in frustration and a loss of self-concept by the player [16]. Research shows that emotions are the lifeblood of every team and every winning athlete. Successful coaches inspire strong emotional connections between the players and the coach and among the players themselves [17]. Coaches who lead with self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skill create a team environment conducive to enjoyment, trust, and maximal effort on the part of the athletes [7]. Research at the South Australian Sports Institute, in conjunction with Swinburne University, has investigated the potential role of emotional intelligence in sport. Previous empirical studies in this area have indicated that the construct of emotional intelligence provides an athlete with an understanding of their specific emotional competencies, and therefore a better understanding and awareness of how to use emotions in sport [4].Coaching is both art and science. The good coach applies scientific principles and techniques, but the great coach applies them with fitness and tact. The coach has an opportunity not only to build skills, but also to reinforce character [10]. The players, not the system are the keys to good coaching. The coach must use every opportunity to reinforce desirable personality traits that enable the individual to be contributing factor in our culture. A fine coach must be unselfish, and keep her own ambitions and need for prestige in the background. A coach must be careful not to destroy an athlete’s confidence while trying to improve her performance, since psychological damage can take as long to heal as well as physical stress.Coaching is never an easy task as it takes a good leader to do so. It is a very tough job. It is not about holding position to impress people of the coach’s exemplary qualities. It really entails great responsibility and accountability. While some reject the role, others enjoy it because of the prestige it gives after a successful and fruitful job of raising their clienteles to the top. Full efforts plus the real passion poured into coaching by the coaches are necessary and undeniably matter a lot.In a study conducted, it was found that coaches and instructors are characterized by average level of emotional intelligence and the sense of self-efficacy [13]. Studies revealed that coaches are characterized by significantly higher levels of emotional intelligence, and the belonging to the group of trainers has no influence on the sense of efficacy. Another study revealed that emotional intelligence was positively associated with work experience but was not significantly associated with age and in academic achievement [15]. It was also found that emotional intelligence significantly affects getting along behaviors. Their study showed that there was a positive relationship between the getting along and getting ahead leadership behaviors. Also, it showed that displaying collaborative behaviors was significantly related to subsequent getting ahead behaviors, which are associated with the visioning and inspirational side of leadership [8].It was found that the athletes’ most favorite coaching behaviors of coaches are classified in social support dimension which is characterized as coach showing concern for the welfare of the individual athletes, providing a positive group atmosphere and providing warm personal relationships with players [16]. The descriptors in this dimension were caring, understanding, friend, respectful, supportive, fun, enthusiastic, fair, role model and honest. A study showed that the scale and subscales of coaches’ emotional intelligence are associated with the scale and subscales of coaching efficacy [1]. The coaches’ emotional intelligence was considered as a good predictor of coaching efficacy. Generally speaking, there is a significant relationship between emotional intelligence as a variable affecting the coaching efficacy [8]. Additionally, another study found that student-athletes who reported their coaches as having higher levels of technical expertise reported higher levels of emotional stability, interest/enjoyment, competence, fitness and social motivation [2]. Lower levels of perceived stress were reported by student-athletes who rated their coaches as being more likeable. Findings suggested strong positive relationships between coaching technical expertise and several motivational factors including interest/ enjoyment, competence, fitness, and social.It was posited that enabling is the leadership practice most frequently engaged in by coaches likewise their colleagues [5]. Students rated this practice as second most engaged in, with Inspiring as the behavior they perceived as most frequently exhibited by their coaches. Coaches, athletic directors, and peers reported Inspiring as one of the least frequently engaged in leadership behaviors. Between coaches and their supervisors there were no significant differences between their scores on any of the five leadership practices or four components of emotional intelligence.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

- Descriptive correlation approach is used for this study. For this study, the coaching behavior of sport coaches is chosen as the independent variable while respondents’ personal characteristics and emotional intelligence are considered as independent variables. Correlation procedures were employed to determine the relationship of the independent and dependent variables of the study. It used descriptive research which involves the collection of data in order to test the hypothesis to answer related questions to present status of subject of the study.

2.2. Data Collection Tools

- Data of all variables is collected through survey questionnaires. The questionnaire for the sport coach-respondent consisted of two parts. The first part refers to questions on the Emotional Intelligence self-evaluation and the second part is the Coaching Behavior Assessment by the Sport Coach. The questionnaire for the athlete-respondents consisted of two parts: the Emotional Intelligence of My Coach and the second part was the Coaching Behavior Assessment – Athlete’s Evaluation of the Coach.

2.3. Sampling Techniques and Sample

- The quota sampling method was used in the selection of the respondents. In this study, the researcher decided to include 20 coach-respondents and 90 athlete-respondents in every state university and college in Region III. However, it was only in Tarlac College of Agriculture (TCA) and Aurora State College of Technology (ASCOT) that the quota of 20 coach-respondents was met. The quota of 90 athlete-respondents was not reached in all state universities and colleges in Region III. A total number of six hundred sixty-two respondents divided into two groups were included in the study. First, the sport coaches from state universities and colleges in Region III who self-evaluated their own emotional intelligence and coaching behavior. Second, the athletes who also assessed their coaches’ emotional intelligence and coaching behavior using same questionnaires but rephrased for the respondents’ better comprehension of each item.

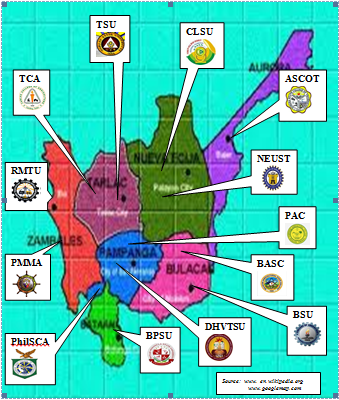

2.4. Research Locale

- The study was conducted in thirteen higher education institutions (HEIs) in Region III subsidized by the national government, called the State Universities and Colleges (SUCs). The following are the HEIs used in this study: 1.Bulacan State University (BulSU Gold Gears), Malolos, Bulacan 2. Ramon Magsaysay Technological University (RMTU Blue Jaguars), Iba, Zambales 3. Philippine State College of Aeronautics (PhilSCA Iron Eagles), Floridablanca, Pampanga 4. Nueva Ecija University of Science and Technology (NEUST Phoenix), Cabanatuan City, Nueva Ecija 5. Tarlac State University (TSU Maroons), Tarlac City, Tarlac 6. Tarlac College of Agriculture (TCA Jets) Camiling, Tarlac 7. Pampanga Agricultural College (PACers) Magalang, Pampanga 8. Central Luzon State University (CLSU Green Cobras) Munoz, Nueva Ecija 9. Bataan Peninsula State University (BPSU Stallions), Balanga, Bataan 10. Aurora State College of Technology (ASCoT Dolphins), Baler, Aurora 11. Philippine Merchant Marine Academy (PMMA Marines), San Narciso, Zambales 12. Don Honorio Ventura Technological State University (DHVTSU Wildcats), Bacolor, Pampanga 13. Bulacan Agricultural State College (BASC Soaring Hawks), San Ildefonso, Bulacan. The map of Region III (Figure 1) shows the location of the SUCs.

| Figure 1. Map of Region III (Central Luzon) showing the location of the State Universities and Colleges |

2.5. Data Analysis

- The study utilized a descriptive statistics in analyzing the collected data. Test for central tendencies were computed and these include the means, standard deviations, and variances. Results were sorted out and tallied which were presented in percentage form. The researcher utilized t-tests and Pearson R correlation tests to identify significant differences and correlation between independent and dependent variables.

3. Results and Discussion

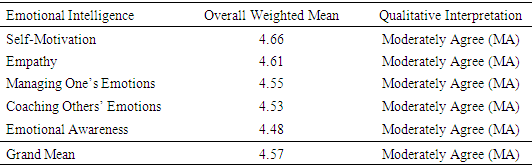

3.1. Coach-Respondents’ Perception on Emotional Intelligence

- Table 1 presents the sport coach-respondents’ perception of emotional intelligence. Among the indicators of emotional intelligence, self-motivation obtained the highest overall weighted mean of 4.66 followed by empathy which acquired an overall weighted mean of 4.61. The rest of the indicators of emotional intelligence obtained an overall weighted mean of 4.55 for managing one’s emotions, 4.53 for coaching others’ emotions, and 4.48 for emotional awareness. It is worthy to note that all indicators of emotional intelligence are accorded the qualitative interpretation of moderately agree. This can be attributed to the fact that sport coaches consider the critical role of emotional intelligence in developing rapport to become effective and efficient in performing multiple roles as coach. Findings of the study revealed that among the indicators of emotional intelligence, emotional awareness and coaching others’ emotions are the least among the five indicators of emotional intelligence. This implies that there are instances when sport coaches find it challenging to recognize negative feelings moreover, use these to help them improve their lives. With that, studies imply that there is a need to strengthen the emotional intelligence of sport coaches in Region III through seminars, workshops, and other available means. Although the coaches believe that they should possess high emotional intelligence in coaching different athletes with different personalities, their behavior as a person still prevail.

|

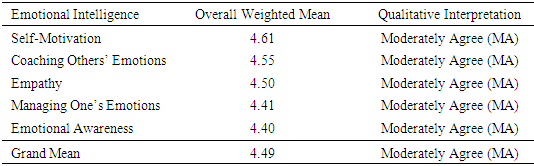

3.2. Athlete-Respondents’ Perception on the Emotional Intelligence of the Sport Coaches

- The overall perception of athlete-respondents toward the emotional intelligence of the sport coaches obtained an overall weighted mean of 4.49 which is accorded a moderate perception or moderate agreement. Among the five areas or indicators of emotional intelligence, self-motivation is deemed to be highly valued by the athlete-respondents among sport coaches. This is followed by coaching others’ emotions which obtained a weighted mean of 4.55, empathy (4.50), managing one’s emotions (4.41), and lastly, emotional awareness (4.40). It bears stressing that all the five indicators and areas of emotional intelligence are interpreted as moderately agreed by athlete-respondents. Athlete-respondents described that their sport coaches have very acceptable, high, and definite strength in their emotional intelligence. This is parallel with the findings that student-athletes reported that coaches who possess higher level of technical expertise tend to have higher level of emotional stability, interest/enjoyment, competence, fitness, and social motivation [6]. Like the coaches, the athletes gave similar assessment of the emotional stability of their coaches. They moderately agree that managing athletes require high level of emotional intelligence.

|

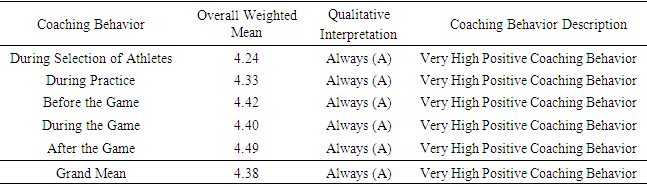

3.3. Sport Coach-Respondents’ Perception towards Coaching Behavior

- Data gleaned from this study revealed that sport coaches have strong sense of awareness of their role in handling athletes. Additionally, sport coach-respondents’ perception of their coaching behavior reveal that they are well aware how to act and deal with situations, manage selection of athletes, practices, before, during, and after game events. These are reflected on the mean scores obtained on the following coaching behaviors: after the game (4.49), before the game (4.42), during the game (4.40), during practice (4.33), and during selection of athletes (4.24). Overall weighted mean of 4.38 indicate a very high positive coaching behavior by sport coaches which implies that they display proper decorum and adhere to the standard coaching behavior expected of them. The coaches’ rating of their coaching behaviour is very high positive in all stages of the games. Selection of athletes by the coaches is very critical in order to win, coaches should not select based on attachment to the athletes but based on competence and strength especially for sports that require physical strength. Table 5 presents the findings of the study with regard to sport coach-respondents’ perception toward coaching behavior.

|

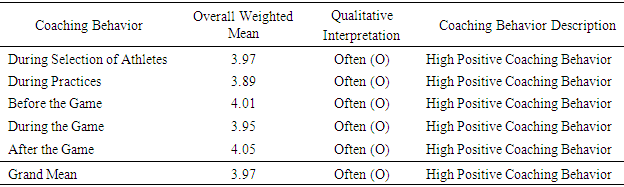

3.4. Athlete-Respondents’ Perception towards Coaching Behavior of Sport Coaches

- An overall mean score of 3.97 interpreted as often indicates that the sport coaches were perceived by athletes to have high positive (HP) coaching behavior. Among the coaching behaviors exhibited by sport coaches, athlete-respondents deem the sport coaches’ behavior to be highly positive after the game (4.05), before the game (4.01), during selection of athletes (3.97), during the game (3.95), and during practices (3.89). This implies that the athletes themselves consider their sport coaches’ behavior to be at the optimum and are highly satisfied with their performance. Additionally, they acknowledge and recognize their sport coaches’ competence in handling athletes. Findings of a study is parallel with what have been posited that sport coaches provide a positive group atmosphere and warm personal relationships with players [12]. In the same vein, it was stressed that coaches who lead with self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skill create a team environment conducive to enjoyment, trust, and maximal effort on the part of the athletes [16]. Table 6 shows the athlete-respondents’ perception towards coaching behavior of sport coaches.

|

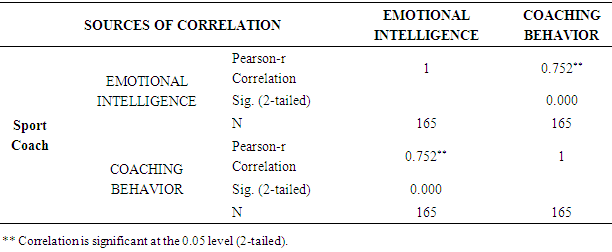

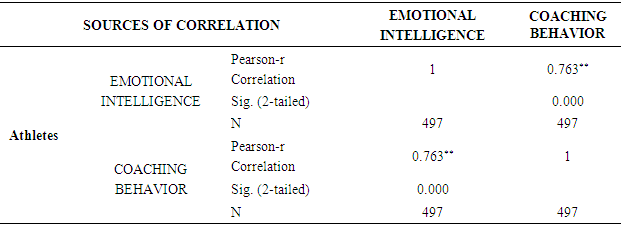

3.5. Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Coaching Behavior of Sport Coaches

- Table 5 shows that the computed significant value of (0.000) between emotional intelligence and coaches’ coaching behavior which is lower than the tabular value of 0.05 alpha level of significance. The result indicates that emotional intelligence and coaching behavior are related. The same finding was obtained in as study that the coaches’ emotional intelligence was considered as a good predictor of coaching efficacy [1]. It has been stressed in the findings that coaches who had high self- awareness and self-regulation had better game strategy effect and coaches who owned high self- awareness and social skills had high instructing technique effect [1]. Table 6 shows the test of significance of the Pearson-r between emotional intelligence and coaching behavior as perceived by athlete-respondents. The Pearson-r value of 0.763 shows that emotional intelligence and coaching behavior have high positive relationship. Emotional intelligence significantly affects behaviour [11]. Their study showed that there was a positive relationship between the getting along and getting ahead leadership behaviors. It also showed that displaying collaborative behaviors was significantly related to behaviors, which are associated with the visioning and inspirational side of leadership.

|

|

4. Conclusions

- The sport coaches moderately agree on the sport coaches’ emotional intelligence along the five areas namely: emotional awareness, managing one’s emotions, self-motivation, empathy, and coaching others’ emotions. Among the five areas, the average mean of emotional awareness was the lowest while the average mean of self-motivation was the highest.The athlete-respondents’ perception on statements describing the sport coaches’ emotional intelligence along the five areas namely: emotional awareness, managing one’s emotions, self-motivation, empathy, and coaching others’ emotions was agree moderately. Among the five areas, the average mean of emotional awareness was the lowest while the average mean of self-motivation was the highest.The coaching behavior of the sport coaches displayed during selection of athletes, during practices, before the game, during the game and after the game as perceived by the coaches was described as very high positive.The coaching behavior of the sport coaches displayed during selection of athletes, during practices, before the game, during the game and after the game was perceived by the athletes as high positive.There is a significant high positive relationship between emotional intelligence and coaching behavior of sport coaches as perceived by both sport coaches and athlete-respondents.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML