-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2017; 7(2): 25-28

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20170702.01

Achievement Motivation of Collegiate Athletes for Sport Participation

Shelley L. Holden, Steven F. Pugh, Neil A. Schwarz

Department of Health, Kinesiology, and Sport, University of South Alabama, Mobile, United States

Correspondence to: Shelley L. Holden, Department of Health, Kinesiology, and Sport, University of South Alabama, Mobile, United States.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The purpose of the study was to analyze collegiate athletes’ achievement motivation for sport participation. Participants included 64 male (n=28) and female (n=36) athletes at a Division I institution in the Southeastern United States. Volunteer participants were current members of the baseball, men’s and women’s basketball, cross country, football, men’s and women’s golf, soccer, softball, men’s and women’s tennis, track and field, and volleyball teams. Separate 2 x 2 univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) procedures were conducted for each of the six dependent variables on the Achievement Motivation Scales for Sporting Environments Survey (Approach-Success (MSO), Avoidance- Failure (MFO), Approach-Success in Competition (MSC), Approach Success in Training (MST), Avoidance-Failure in Competition (MFC), and Avoidance-Failure in Training (MFT)). There was a statistically significant interaction between gender and sport team participation for MSO and MST. Male team sport athletes scored significantly higher on the MSO and MST variables of the Achievement Motivation Scales for Sporting Environments Survey than female team sport athletes.

Keywords: Sport, Athletes, Gender

Cite this paper: Shelley L. Holden, Steven F. Pugh, Neil A. Schwarz, Achievement Motivation of Collegiate Athletes for Sport Participation, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 7 No. 2, 2017, pp. 25-28. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20170702.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Motivation may be considered the most important variable in athletics. It can affect sport performance as well as the overall sports experience for an athlete. But what exactly is motivation? How is it defined? And how is it assessed? Motivation has been defined in many contexts, but a widely accepted definition is, “It represents the hypothetical construct used to describe the internal and/or external forces that lead to the initiation, direction, intensity, and persistence of behavior. Thus, motivation leads to action” [16, p. 428]. However, a concern defining motivation is it is not directly observable, but must be inferred from an athlete’s behavior [16]. That is, a coach might determine a player is motivated to perfect the spike in volleyball when he or she would stay after practice and work on footwork drills associated with the skill, but not when an athlete consistently does no more than the minimum required by the coaches. Early studies in motivation laid a base for more theoretical based research because many of these early studies on youth athlete motivation for sport participation were descriptive in nature [5, 6]. That is, they made use of questionnaires that tended to ask participants to rate the importance of a range of participation motives. There are also different types of motivation such as intrinsic and extrinsic. Specifically, are athletes motivated by participating in sport as a means to an end rather than for the sake of the sport experience. If so, they desire rewards external to the sport and are thus, extrinsically motivated [16]. An example would be a volleyball player playing on a volleyball team to win awards, gain notoriety, and attention, etc. that typically accompany this type of success. Deci and Ryan (1985) proposed different types of extrinsic motivation that vary based upon the athletes’ level of self-determination [2]. They considered the lowest level of self-determination to be external regulation, followed by introjected regulation, then identified regulation, and the highest level was termed integrated regulation [2]. External regulation is characterized by behavior regulated through external means such as trophies and medals and avoiding constraints such as social pressures. Introjected regulation is seen in athletes who internalize reasons for their actions. This internalization replaces the external source of control with internal ones (ie. guilt and anxiety). Identified regulation is more autonomy driven and involves consciously valuing a goal so the said action is accepted as being personally important to the athlete [2]. Lastly, integrated regulation involves participating in a sport from an extrinsic perspective in a “choiceful” manner [16]. An example of this might be athletes whose choices are made as a function of coherence with various aspects of oneself such as staying home from a social event to be ready for the match the next day [16]. However, if an athlete is participating in the sport for the sake of the sport experience and the satisfaction or pleasure that accompanies sport participation, then they are said to be intrinsically motivated. An example would be if a volleyball player plays because he or she finds it fun, interesting, and enjoys learning the various skills associated with the game. Vallerand et al. (1992) noted there are three types of intrinsic motivation. These include: a) intrinsic motivation to know, which is characterized by engaging in a sport for the pleasure of learning; b) intrinsic motivation toward accomplishment which is where an athlete participates in a sport for the pleasure of trying to surpass his or her own accomplishments; and c) intrinsic motivation to experience stimulation which is where an athlete participates in a sport out of sensory and aesthetic pleasure [17]. Other studies [4, 15] examined motivation from a task or an ego orientation. The task orientation was associated more with values in sportsmanship whereas; the ego representation was more closely associated with a “product” or a focus on a winning orientation.Still another, more simple, way of defining extrinsic versus intrinsic motivation would be participation for product (external) or participation for process (intrinsic). Other studies such as Pugh, Wolff, DeFrancesco, Gilley, & Heitman (2000) and Pugh (2006) used qualitative methods to examine sports participation motives [12, 13]. Pugh, et al. (2000) found that youth baseball players’ participation motives were fun, self-improvement, and socializing with friends [13]. This would align them most closely with a task, or intrinsic motive. Pugh, (2006) found that middle aged international rugby athletes were also motivated by self-challenge, and social motives [12]. Finally, amotivation, or lack of motivation, may be a reason for not participating. This construct, while not measured by the instrument used in this study, has been associated with individual decisions not participate in activity. Lack of motivation has also been associated with several motivational theories such as, Flow Theory, Achievement Goal Theory, Self-determination Theory and Attribution Theory [1, 2, 11, 18]. There a number of instruments and research methods to assess motivation in athletic populations. Researchers in this study selected the Achievement Motivations Scale for Sports Environments (AMSSE). It was developed by Randy Fox during his Master’s degree program and was later published by Rushall and Fox [14]. The AMSSE is designed to measure “approach-success” and “avoidance-failure” of athletes in training as well as competition settings [14]. Success-strivers are motivated to achieve, while failure avoiders are motivated to avoid failure in training and/or competition. It is important to note separate measurements must be taken for these conditions because athletes may approach the training environment different than the actual competition [7]. Therefore, the purpose of the study was to analyze collegiate athletes’ achievement motivation for sport participation based on gender and sport team participation (individual vs. team sports).

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- Participants included 62 male and female athletes at a Division I institution in the Southeastern United States. Volunteer participants were current members of the baseball (n=5), men’s and women’s basketball (n=5), cross country and track (n=3), football (n= 10), men’s and women’s golf (n=2), soccer (n=2), softball (n=6), men’s and women’s tennis (n=2), track and field (n=12), and volleyball (n=15) teams. There were 26 (41.9%) male and 36 (58.1%) female participants. Of this sample there were 19 (31.3%) individual sport athletes, 43 and (69.4%) team sport athletes.

2.2. Instrument

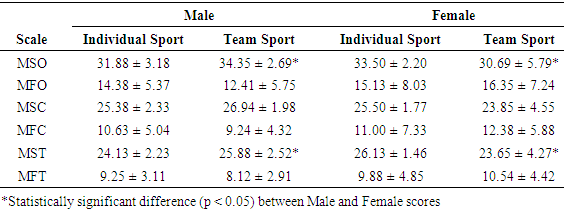

- The Achievement Motivations Scale for Sports Environments [14] was used in this study. This instrument is designed to measure “approach-success” (MSO) and “avoidance-failure” (MFO). Results then indicate scores for six psychological variables. The approach scales indicate positive motivations such as incentives, expected positive reinforcements, high-probability, goal achievement, etc. which exist in the sport or the components of training and competition [14]. Avoidance scales are interpreted as negative features that promote participation such as compulsory activities, avoidance of negative outcomes from not performing, participation due to social pressures, etc. [14]. The idea is sport participation occurs to avoid some sort of consequence. To obtain these scores participants were asked a series of questions to which they must respond: a. always (3 points), b. frequently (2 points), c. sometimes (1 point), or d. never (0 points). The sum total of points for each designated question for the psychological variable is added to produce a factor score. The factors on this instrument are: Approach-Success (MSO), Avoidance- Failure (MFO), Approach-Success in Competition (MSC), Approach Success in Training (MST), Avoidance-Failure in Competition (MFC), and Avoidance-Failure in Training (MFT). The maximum scores for the individual factors are as follows: MSO-39, MFO-45, MSC-30, MST-30, MFC-33, and MFT-27.The overall scores (MSO & MFO) indicate positive or negative reasons for participating in sport [14]. Also, an athlete’s participation can be divided into two sets of experiences (training and competition). Rushall and Fox (1980) noted it could be possible that an athlete could be very positive about training yet be negative about competition [14]. Overall, the AMSSE is useful for determining whether the sport environment is more positive or negative.

2.3. Procedure

- Permission to conduct this study was granted by obtaining Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval from the investigators institution of higher learning. Participation was open to male and female athletes on the baseball, men’s and women’s basketball, cross country and track, football, men’s and women’s golf, soccer, softball, men’s and women’s tennis and volleyball teams. All head coaches where contacted prior to the study to request their team’s participation. Once permission was granted, researchers met with each team individually and were responsible for monitoring the completion of the instrument and demographic questionnaire. Participants were informed of their right not to participate and of the confidentiality of their results.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

- Separate two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were conducted for each of the of the dependent variables in the Achievement Motivation Scales for Sporting Environments survey (MSO, MFO, MSC, MST, MFC, MFT) to examine the effects of the independent variables of gender (Male vs. Female) and sport team participation (Individual Sport vs. Team Sport). Residuals were used to perform the tests for the assumptions of the two-way ANOVA. Normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test and examination of Quartile-Quartile (Q-Q) plots. Potential outliers were assessed by boxplot analysis and Levene’s test was used to test the homogeneity of variances. Surveys with missing data points for the dependent variables were excluded. All data were analyzed using Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and an alpha level of 0.05 was adopted for all tests.

2.5. Results

- Four participants failed to successfully complete the survey and were excluded from further analysis. Additionally, one participant was an extreme outlier on two of the six dependent variables as assessed by the boxplots and eliminated from further analysis. Therefore, data from 59 of the original 64 participants were used for analyses. The assumption of normality was violated in four of the 16 datasets tested by the K-S test (MSO, Males, Team Sport: p = 0.01; MSC, Males, Team Sport: p = 0.03; MFT, Female, Individual Sport: p = 0.02; MSC, Female, Team Sport: p = 0.03). Despite these deviations from normality, a two-way ANOVA was chosen for analyses because visual inspection of the Q-Q plots for each dataset did not reveal significant deviations from normality, most of the datasets did not violate the K-S test, and because of the inherent robustness of ANOVA to deviations from normality [9]. Lastly, Levene’s test for the homogeneity of variances was violated for MSO, MSC, and MST. Data for these dependent variables were transformed using a square transformation because the spread of the residuals decreased with increasing predicted values and the ANOVA tests were then conducted with the transformed data. No difference in results were observed between the raw data and the transformed data, thus, the results of the ANOVA tests using the raw data were reported. Data are presented for each scale in Table 1. No significant main effect for gender or sport team participation or interaction effect between gender and sport team participation were observed for MFO, MSC, MFC, and MFT. Conversely, there was a statistically significant interaction between gender and sport team participation for MSO, F (1, 55) = 4.18, p < 0.05, and MST, F (1, 55) = 4.66, p < 0.05. There was a statistically significant difference in MSO scores between males and females who participated in a team sport, F(1, 55) = 7.16, p = 0.01. For males and females participating in team sports, mean MSO score was 3.66 points, 95% CI [0.92, -6.40] higher for males than females. There was a statistically significant difference in MST scores between males and females who participated in a team sport, F(1, 55) = 4.62, p = 0.04. For males and females participating in team sports, mean MST score was 2.23 points, 95% CI [0.15, -4.31] higher for males than females.

|

2.6. Discussion

- The research findings indicated male athletes in this sample that were involved in team sport participation had a greater approach-success orientation overall than female athletes. Further, it was determined that male team sport athletes had a higher approach-success at training than the female team sport athletes. Prior research has typically found that males have more of an ego approach to training and competition than female athletes which would support the current findings. Moreover, the results also support the notion that female athletes generally display a task orientation in training and competition. Heuze et al. (2006) found that the motivational orientation of the female collegiate athletes in their study changed with the temporal relationship of the season and with the environment established by the coaches [8]. This study examined athletes’ motivational orientation at one point in their sport seasons. While the athletes in different sports were in different phases of their individual seasons, their motivation was assessed at only one point in time. This may have been a limitation of the current study. Still, in the current study it is worth noting that the differences in the male and female athletes’ motivational orientations would be an item of interest to the coaches of the athletes in the present study.

3. Conclusions

- Future research could examine female athletes and determine if they are more likely to have a task orientation to sport whereas males are most likely to have an ego orientation. If this is determined, then there are implications for sport participation, social interactions, and the display of sportsmanship for males and females in sport. Further, research could examine whether or not athletes’ motivational orientation changes over the course of a season and if there are identifiable differences in motivational change between sports in males and females and in the types and degrees of change. Future efforts might sample athletes at regular intervals throughout their seasons and analyze data at comparative points in the seasons. Coaches might also examine how their efforts might influence the development of either an ego or task orientation in their athletes. Finally, longer duration studies could possibly test interventions to improve the motivational perspectives of athletes and the impact of coaches’ behavior on the motivational orientation of athletes.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML