-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2017; 7(1): 6-9

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20170701.02

Quality of Life Levels in Brazilian Elite Female College Volleyball Players

Renan F. Correia1, Alex N. Ribeiro1, João F. Barbieri1, Douglas Brasil1, Leonardo Motta2, Luz A. A. Castaño3, Mariangela G. C. Salve4

1Faculty of Physical Education Graduate Program, State University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil

2Faculty of Physical Education Undegraduate Program, State University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil

3Technological University of Pereira, Pereira, Risaralda, Colombia

4Department of Sports Sciences, State University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil

Correspondence to: Renan F. Correia, Faculty of Physical Education Graduate Program, State University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

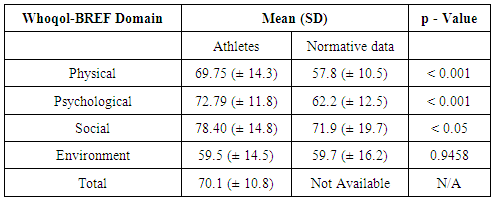

This article investigated quality of life levels and indicators in Brazilian elite female college volleyball players. Thirty-two athletes participated in this cross-sectional – survey type study, by answering two protocols: the WHOQOL-BREF and an academic-sports questionnaire developed by the authors. The athletes displayed high quality of life, showing results higher than the normative data presented for a random Brazilian female population in all its domains, except for the environment domain. The athletes showed discontent with the organization of university sports in Brazil, especially in relation to its schedule planning, which always conflicted academic and sportive activities, thus hindering both their training and academic formation. It is expected that this research will contribute to the continuing advancement of the investigations of the relationships between the practices of high-performance sports, be it collegiate or professional, and quality of life.

Keywords: Quality of Life, Volleyball, College Sports

Cite this paper: Renan F. Correia, Alex N. Ribeiro, João F. Barbieri, Douglas Brasil, Leonardo Motta, Luz A. A. Castaño, Mariangela G. C. Salve, Quality of Life Levels in Brazilian Elite Female College Volleyball Players, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 6-9. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20170701.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Just like their professional peers, collegiate athletes undergo strenuous periods of sport-specific training to maintain the high performance levels required in the competitive context of college sports [1, 2]. There is also the need to conciliate their athletic duties with that of a student lifestyle and its many particularities, such as studying, tests, and other academic activities. These factors, when added to other nuances of a teenager’s daily life, such as economic conditions, social life, family and personal relationships can influence their quality of life (QoL), especially regarding practices that may influence their health or academic formation [3]. Unlike in most countries, the scientific literature regarding college athletes in Brazil is very scarce [4]. Thus, this article aims to investigate quality of life levels and indicators in this specific population. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines Quality of Life (QoL) as an Individual’s own subjective perception of their position in life in relation to their particular goals, expectations, standards and concerns. It is a broad concept, influenced by an individual’s physical and psychological health, level of independence, relationships with their peers, the environment, among many other domains of life [5].In the present day, the practice of physical activity is considered an essential behaviour for the improvement of QoL levels of society [6]. In contrast, there is a perception in various academic circles that high-performance sport, because of its highly organized, physically and mentally challenging and environments, may not be a QoL improvement agent and may even seriously undermine it [7, 8]. However, this perception lacks academic evidence. As the starting point for this research, it is necessary to start from the impartial notion that: "Sport alone does not give or take away anyone's health [...] and the practice of high-performance sports cannot be considered as essentially negative to the quality of life of the athlete, just as leisure sports cannot be considered as totally beneficial." (Authors’ translation [9, p.97]

2. Methods

- This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Campinas, protocol number 711/211, which establishes the Norms and Guidelines for scientific research involving human beings – according to Brazil’s Ministry of Health Resolution CNS 196/96. All study participants signed informed consent forms.The cross-sectional - survey style study consisted of thirty-two athletes, mean age 22.5 (± 3.48) years, of 5 teams from four different Brazilian states, who participated in the final phase of the University Sports National League held in Brasília, in September of 2011.The athletes answered two protocols:A) The WHOQOL-BREF, developed by the World Health Organization (10) and validated for the Brazilian population [11]. It consists of 26 questions: 24 questions divided into four domains (physical, social, psychological and environmental), and two general questions about QoL. Specifically, the domains refer to:• Physical domain: physical pain, energy, locomotion, daily life activities, medical treatment, work, etc• Social domain: social support, sexual activity, personal relationships, etc• Psychological Domain: positive feelings, concentration, self-esteem, self-image, negative feelings, spirituality, etc• Environmental Domain: physical security, housing, financial resources, health services accessibility, information, leisure, physical environment, transportation, etcThe scores in the WHOQOL-BREF range from 0 (worst) to 100 (optimal). The higher the values, the better the individual's QoL indicator for that domain [12].B) A questionnaire developed by the authors, denominated the Academic-Sports Questionnaire, which asked athletes personal questions about their daily life, such as how many hours a week they spent on training, study and leisure, whether or not they received a scholarship from their college, and opinions about the organization of the university championships. With this questionnaire, the authors hoped to learn more about the particularities of the athletes’ daily routine and lifestyle, as well as their opinions about university sports in Brazil.To score and analyze the WHOQOL-BREF data, the authors used Graphpad Prism 6.07 software [13]. First, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to analyze data normality. Subsequently, descriptive (mean, standard deviation) and inferential statistical tests were performed. Student's T test compared the subjects’ QoL scores with normative data for a random Brazilian female population [14] and Pearson's coefficient correlated the QoL variables with data such as time dedicated to training and studying. 95% significance level was adopted for all tests.

3. Results

3.1. WHOQOL-Bref

- The results displayed by the athletes in the different WHOQOL-BREF domains were numerically high, indicating a high quality of life (Table 1). When compared to normative data, there were statistically significant differences in the physical, psychological and social domains (p <0.001).

|

3.2. Academic-Sportive Questionnaire

- • The athletes devote on average 20 hours a week to their training.• According to the Pearson coefficient, there is no significant correlation between training hours / week and QoL levels (r = -0.10).• All athletes receive full or partial scholarships from their respective universities. Twenty-eight of the athletes said they depend on their scholarships to continue their studies.• 29 of the 32 athletes responded that the calendar of university competitions conflicts with their academic calendars. Twenty-six of the 33 athletes think that a better time of the year to take place in these championships would be during the school holidays or vacations.• 19 of the 32 athletes would like to have more time to study.

4. Discussion

- QoL levels measured in the athletes by the WHOQOL-BREF were high, especially in the physical, psychological and social domains when compared to the normative female Brazilian population. Thus, it can be implied that, according to the WHOQOL-BREF, the athletes in this study have higher QoL levels than the normal population. These findings help to further deny the hypothesis that high-performance university athletes have lower QoL levels than their non-athletes counterparts. These results were not expected by the authors, especially considering that the research was done during the athletes' competitions, when stress levels are high [3], and may contribute to worsening of QoL levels, which was not noticed in the results obtained. The high scores in the physical domain of the WHOQOL-BREF can be explained by the fact that the athletes practice daily physical exercise, monitored by coaches and physical trainers, have qualified medical and psychological assistance in their respective teams, and have balanced diets. These results reinforce the close association between sport and health, due to the role attributed to sport practice in the configuration of healthy lifestyles [6]. Despite the risk of injury associated with sports practice, this did not seem to influence athletes' responses. Houston et al [15] inquired about the relationship between injury incidence and health-related quality of life in university athletes and obtained a negative correlation between the two variables. However, it should be noted that the methodology used by the authors considered only the domains of health-related QoL, whereas the use of the WHOQOL-BREF does not restrict the QoL question only to the health domain.The high scores in the psychological domain can be explained by the high levels of concentration attributed to athletes, and the fact that many of the athletes interviewed have professional psychological support in their teams. Sport itself encompasses ideals of overcoming and accomplishment [3]. Some studies show that young athletes have better self-esteem than young non-athletes [16]. Another fact that cannot be ignored is that the athletes in question are very experienced, and by integrating a high-performance team, they went through countless stages to get to where they are, realizing personal dreams and goals along the way, which contributes a lot for their self-esteem and psychological state [17]. This hypothesis, which takes into account the experience of the athletes, is the same one raised by Teixeira et al [18] in their study, who found no evidence of burnout in volleyball youth athletes, and highlighted a positive correlation between experience and indicatives for Burnout Syndrome. These results are even more surprising when one considers that some authors, such as Feijó [19] states that volleyball is the collective sport in which there is the psychological tension, since the teams have no physical contact with the opponents and the space to be occupied by the athletes is delimited by a net, and can not be invaded. Also, Martinovic et al [20] reports that volleyball has a set of requirements that can generate stressful situations.The high scores in the social domain can be explained by the fact that the athletes are inserted in a team ideal, where bonds of friendship are created due to the daily coexistence [21], and focused on a common ideal: the success of the team. The scientific literature shows that competence in the areas of physical activity can often lead to social competence or social acceptance [22, 25]. The fact that all athletes receive some type of scholarship from the Universities they belong and state that they depend on this scholarship to study helps explain the high score in the social domain, since the insertion in higher education can help the athletes to relate better to the society in which they are inserted [26, 27]. The score obtained by the athletes in the environmental domain was the only one that was not statistically higher than that of the normative population. Studies [28, 29] argue that organizational discontent, especially with sports confederations, is a major source of stress in high-achieving athletes. The athletes showed their dissatisfaction with the planning of dates of the competitions. 90% of the athletes responded that the calendar of university competitions conflicts with their academic calendars. 79% of the athletes think that the best time of the year to hold these championships would be during the school holidays or vacations. The National University Games in 2011, for example, was in November, a month that coincides with the school semester. Another example of this situation was the data collection of this study during league play, which was done in September, also in the middle of the winter semester. Athletes devote on average 20 hours a week to training with their respective teams, which can be compared, for example, to a part-time job. Pearson's coefficient did not show, however, a correlation between the long hours and QoL levels. Therefore, it is concluded that in this case, that the long time dedicated to training did not interfere in the athletes' QoL. Despite this, 60% of the athletes interviewed said they wished they had more time to study. Holden et al’s [30] research raises a possible explanation to this, by bringing us data that shows that athletes in scholarships are more likely to suffer academic pressure.This scenario can also be explained by the fact that for most athletes, this is their first time living away from their families and homes. According to FLETCHER and HANTON [25] this demands financial and organization conscience from the athletes, which undoubtedly affects training and studying environment.

5. Conclusions

- The athletes interviewed had high QoL levels in the WHOQOL-BREF. Their results were higher than the normative data presented for a random Brazilian female population in all its domains, except for the environment domain. The athletes showed discontent with the organization of university sports in Brazil, especially in relation to the schedule of competitions, which always conflicts with the schedule of classes, and thus could hinder their training and academic formation.This study presented some limitations, mainly regarding the number of athletes who were interviewed. However, it should be noted that, although small, the number of athletes is proportional and representative to the universe of university volleyball players in Brazil. In the future, it is expected that more studies will be done on this subject with more athletes, of both sexes, participating in other college sports.Finally, it is expected that this research will contribute to the advancement of the investigations between the relationships between the practices of high-performance sports, be it collegiate or professional, and QoL.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The CNPQ (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development) provided funding source this research through its institutional program. The funding source had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, nor in the writing and decision to submit the finished article.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML